Celtic Heads

Celtic Head from Witham, 2nd c B.C. (British Museum) "Celtic" carved heads are found throughout the Read more

Timeline 60BC – 138AD

This timeline is focussed on the British Celtic culture and those cultures which had influence on the British Celts. It Read more

Cartimandua

Yorkshire, and much of northern Britain was also ruled by a queen, the most powerful ruler in Britain in fact. Read more

Caratacus

Caratacus was highly influenced by the Druids, and both he and his brother Togodumnus were among the leading lights of Read more

Cerialis Petillius

Quintus Petillius Cerialis Caesius Rufus was the son-in-law of Vespasian Cerialis and became Governor of Britain in AD.71; his instructions Read more

Julius Caesar

Ask anyone to name a famous Roman character, and the name of Julius Caesar is sure to be the most Read more

Vespasian

Born in the year 9 at Reate, north of Rome, Vespasian was the son of a tax collector, Flavius Sabinus Read more

Augustus

Suetonius wrote of him: He was very handsome and most graceful at all stages of his life, although he cared Read more

Claudius

Tiberius Claudius Nero Germanicus was born Lugunum in 10 BC, the youngest son of Nero Drusus, brother of Tiberius. He Read more

Celtic Gods

Many Celtic deities seem to have been associated with aspects of nature and worshipped in sacred groves. Some appear in Read more

As a person of Welsh descent, it is disappointing to have to face up to the fact that the Welsh connection to the story of Arthur has been almost irretrievably subsumed by the enthusiastic input of a plethora of external sources. The filigreed embellishments of an ever-expanding number of Arthurian afficionados have diminished the kudos of dusting off lost fragments of history. It doesn’t quite stir the imagination somehow. After all, why spoil a rollicking good adventure by further unsettling shaky realities?

But it needs to be said that the Welsh connection has actually got the real potential to provide a solid trail of tantalizing clues and hints and tangible evidence that can weave a whole new interpretation into the events of the past…

…just by letting the language take the role of leader while you faithfully follow its track, just to see where it goes.

It has worked before with words that don’t confound the English tongue. We’ve been happy to identify Arthur’s burial ground as being on the Isle of Avalon (an island of apples) and we have no problem accepting this as being a translation of the Welsh word ‘Afal’ – meaning apple, even though the plural for ‘afal’ in Welsh is actually ‘afalau’ (not Afalon). We accept that Welsh is a funny language, so it’s natural that we might not get it 100% right.

Similarly, it’s generally acknowledged that the name Gwenivere, Arthur’s queen, must be Welsh in some way because “gwen” is the Welsh word for ‘white’, and Gwenivere, at a stretch can be ‘sounded’ in Welsh as “Gwen-eferwi”…which means “bubbling whiteness”.

Arthur’s father, Uther Pendragon, also has a name that has been systematically dissected and explained for its Welshness : ‘pen’ meaning ‘head’, and ‘dracon’ in Old Brythonic (Welsh) meaning ‘leader’, with these two words being the root cause of long-term dramatic results when the Romans historically confused the word ‘dracon’ with the Latin ‘draco’ meaning ‘serpent’ – thereby giving birth ultimately to the dragon on the Welsh flag. So that in reality, there were no mythical dragons, just one big fierce-looking, angry-sounding, fire-breathing clan chief. Curiously also, Uther Pendragon is suspended between reality and myth as a result of his name. His title ‘Pendragon’ describes his (or anyone else’s) position and standing in the community in pre-Roman/Celtic times, while his given name ‘Uther’ marks him as a particular character with a role in the Arthurian legend.

We accept these snippets of Welshness because they don’t despoil the magical myth, but rather, help to add mystical elements to the story.

But we are not so sure when the Welsh language dares to give us an extra twist, such as, let’s say, a “treigliadd” or a “trickle mutation”, which is a grammatical facility whereby the first letter of a second word changes in order to make it easier to say. This is what has happened when we learn that Arthur’s final battle took place at the battle of Camlann – or Cam-glan, with the dropped ‘g’ so that it becomes “a crooked (river) bank” in translation – something more mundane than the sound of the word might suggest.

However, none of these oddments can prepare us for the utter misdirection which has resulted from a misunderstanding of the simple Welsh word for ‘the’ – ‘y’ or ‘yr’. The confusion over this particular word is so profound that it needs to be isolated and examined in and of itself.

‘Y’ and ‘yr’ have been tragically mispronounced by the English and some serious red herrings have arisen as a result. ‘Y’ has been used fondly as a mark of respect in the past, as in “Yr Hen” – ‘The Old”, and to this day, the word ‘y’ is still used to name and separate different identities in Wales, as in Jones the butcher, Jones the baker, and Jones the candlestick maker (Jones y Cig, Jones y Bara, Jones yr Olau)

It is not spoken with an ‘i’ sound, or an ‘ee’ sound, but rather as a lazy ‘er’. In fact, the best way to grasp the pronunciation is to copy the sound of the word ‘Sir’ without the ‘s’.

And this can lead into a whole new field of discovery…which hinges on the word ‘Sir’ as it is derived from the French ‘mon-sieur’ (my lord). The French connection is important because the legend of Arthur doesn’t really come alive until the French-Norman invasion of Britain in 1066, (co-incidentally about a hundred years after the poem “Y Gododdin” was first recorded in the 9th century).

It is difficult – at this distance in time – to imagine a world where French was the predominant language spoken in Britain, but for 300 hundred years, English was the patois of the peasants, Welsh was the tongue-twisting gobbledegook that the Saxons suppressed as they established their four- hundred-year (6th-10th) reign of dominance, and French became the language of the hierarchy within the castles and courts the length and breadth of the country from 1066 to 1385.

Contrarily, it is easy to imagine how the arrival of the French might have heralded a renewed interest and revival of the Brythonic language since these two Gallic cousins shared many linguistic similarities, with some words even sounding exactly the same : llyfr/livre – book, ffenestr/fenetre – window, mor/mer – sea, mur/mur – wall, trist/trist – sad, pont/pont – bridge, eglws/eglise – church, to list a few examples. But this crossover and pairing of words with similar Latin roots was not without its problems and mismatched results. The Welsh word ‘Y’ being one of them.

Just imagine the buzz around the ladies of the French-speaking courts as the Norman castles expanded into the north of the country and into the historic lands of the Brythonic-speaking Gododdyn, and the kingdom of Rheged. Gossip in different languages would have flowed freely among the peasants and servants in the marketplaces, kitchens and alehouses, and whispered into the ears of the nobility in their private quarters. Bardic verses about the exploits of warrior heroes would still have been “sung” among the surviving Celts, even though the Saxons had pushed their tribes to the western fringes. And, for the French, the funny-sounding names would have rolled more easily of the tongue than for the English. Galahad, Gawain, Tristan, Percival, Gareth, Lancelot, Kay were all names that would have been spoken with an easy familiarity. Yet these identities were nowhere to be found in Celtic times.

The only name that crops up – in the negative – is that of Arthur in the poem ‘Y Gododdyn’ when Aneurin, the poet, wrote of the leading warrior of the day, saying that he was not Arthur – “ d’oedd o ddim Arthur”. And, of course, the other name we hear is that of Uther, his father. Added to which, these two names closely resemble the Welsh word “rhuthr” meaning, ‘rush’, or ‘charge’.

Uther, Arthur and rhuthr, all sound the same in Welsh. In fact, it is too easy to see how they might have been confused and mistranslated as the story was orally narrated down the ages.

Even so, these words only take on special significance when you add the word ‘Y’ to them in the Welsh way. Then, when spoken out loud in a Welsh accent, the sounds are virtually indistinguishable. Yr Uther, Yr Arthur, and Y Rhuthr blend into one, meaning : “the leader of the charge”.

In isolation, this might seem like nothing more than an interesting minor detail, but when you apply the same linguistic quirk to some of the other leading “knights of the round” table, a whole new picture begins to emerge.

The most revelatory knight to apply this system of nomenclature to would be Sir Gawain. Gawain, spelt Gwain in Welsh, is a ‘scabbard’. Sir Gawain thus becomes “Y Gwain” – The Scabbard. In the same vein, Sir Galahad, with some adjustment, becomes “Y Galwad” – The Caller. Sir Kay becomes “Y Cau” – The Closer. Sir Percival – becomes “Y Perisigl” The Shaking Spear. Sir Gareth becomes “Y Garreg” – The Pebble. Sir Tristan becomes “Y Trist” – The Sad. Sir Lancelot becomes “Y Llawn-selog” -The (one who is) Full-of-Zeal (Latin).

These adjustments, when you include “Y Rhuthr” – The Leader of the Charge, take on a far more militaristic bias than the original naming of the Knights of the Round table would allow.

The French, with their linguistic penchant for sliding the letters of words into one another, took a functional descriptor and elevated it into a lordly title. “Y Cau” become(s-S)yr Kay” with sublime ease thereby resulting in the creation of a class of lordly heroes, rather than a band of warriors with a particular role in battle.

A fragile concoction resulted which had nothing to do with the pseudo-historical facts recorded by Gildas or Nennius, but was more in line with the heroic panegyric of Aneurin’s “Y Gododdyn” as it was captured and embellished by the jealous fancies of francophile courtiers to be later fixed into the record books by Geoffrey of Monmouth.

But if that Arthurian fantasy were to unravel at this distance in time, what realities would we be left with?

No-one knows how a Celtic battle might have been conducted back in the 1st– 4th centuries. Certainly, we know that Roman warfare was highly structured, whereas the Celtic forces they came up against in Gaul and Britain have been depicted as a wild rabble. They weren’t trained soldiers in the way the Romans were. But that doesn’t mean that they didn’t have some kind of battle plan and organization.

The Romans overwhelmed the Celts systematically when they took Britain, but as the Roman forces became stretched and weakened along the fringes of Empire, they resorted to parlaying with the local tribes to the north to act as their proxy armies in keeping the untameable Picts at bay.

When the Romans were forced to retreated from the Antonine Wall in 160AD, they made use of a confederation of Brythonic-speaking peoples who saw themselves as being separate groups of equal-standing led by their own chiefs. Not so much conferring at a “round table”, as at a ‘table of crowns’. The Welsh word ‘cron’ meaning ‘round’ being indistinguishable, orally, from the word ‘coron’ meaning crown. Their old beliefs in reincarnation would still have been alive in their minds and would have sustained them in battle. To be reborn as a more prestigious person by dying courageously in battle would still have mattered in the 2nd century. Their old battle-cry of : “Escar-i-fore”, meaning ‘a rebirth to the morning’ would have breathed energy into their spirits.

For over three hundred years they patrolled the border in exchange for certain freedoms from the Roman conquerors. They would have been well-practiced at summoning a makeshift army at short notice and organizing peasant farmers into a defensive force.

So that when a new enemy arrived at their shores in the 5th century, they had established systems to fall back on.

And when Merlin led Arthur to the sacred lake to extract the old long Celtic sword – still shiny from having been preserved in an acidic peat bog, and exposed when the “craig” or “rock” split open as the peat loosened out in summer rains, a new ‘Arthur’ (Rhuthyr) might have extracted that sword, held it aloft and cried out “Escar-i-fore!” – a rebirth to the morning…stirring the idea of a renewal of the old ways. And his followers might have enthusiastically echoed his words, possibly making the word sound more like ‘Excalibur’ over time.

The sword would not have been raised out of the water by a ‘lady of the lake’. This is a misunderstanding of translation. The word for a woman, in Welsh, is ‘gwraig’. ‘Craig’, the word for ‘rock’, will mutate the ‘c’ to a ‘g’ according to its position in a sentence, and become ‘graig’. ‘Gwraig’, and ‘graig’ are aurally sufficiently so similar that it is easy to see how the myth of the ‘lady of the lake’ was created.

It is worth noting that a find of an old Celtic sword in the 5th century would have been a precious, rare occurrence. Most of the weaponry that had been thrown into the sacred waters as an offering to the Celtic Gods would probably have been lifted out of the lakes at the time of Boudica’s (Welsh Buddiga, meaning “victory”) rebellion in the 1st century. It is rarely stated that this uprising coincided with Suetonius Paulinus’ torching of the sacred groves of the Druids in Anglesey. The smoke would have been visible throughout Snowdonia and up the west coast of northern Britain, almost to the Lake District. Those Druids who were not at home on ‘Mon’ at the time of the massacre would have heard the news and furiously led the Celts into the sacred lakes to retrieve whatever weaponry was still useable and carried it across to join Buddiga’s forces. (Bearing in mind that Buddiga’s forces burned the Temple of Claudius and all the people sheltering within it to the ground, it is not impossible to surmise that a few avenging Druids might have been seeking retribution and directing matters covertly from within.)

For the next four hundred years, the Druids and their detested religion were suppressed. Whatever loyal adherents remained survived by staying hidden. Merlyn’s Druidic provenance would have been kept secret by the northern tribes. The word ‘merlyn’, in Welsh, means ‘pony’. Merlyn’s role in any battle plan might have been to keep in the background and muster the reserves of horses. But the old Druidic belief in a rebirth by heroic death, would have been essential to the fierceness of the fighting in battle. Merlyn’s presence would have given the warriors spiritual sustenance.

The territory between Hadrian’s Wall and the Antonine Wall was patrolled by the men of “Yr Hen Ogledd” – the old north. Brythonic warriors. Uniquely, the men of “Yr Hen Ogledd” were a fighting force that managed to hold onto their Celtic identity separate from the excessive influence of the Romans. They fought in the old way.

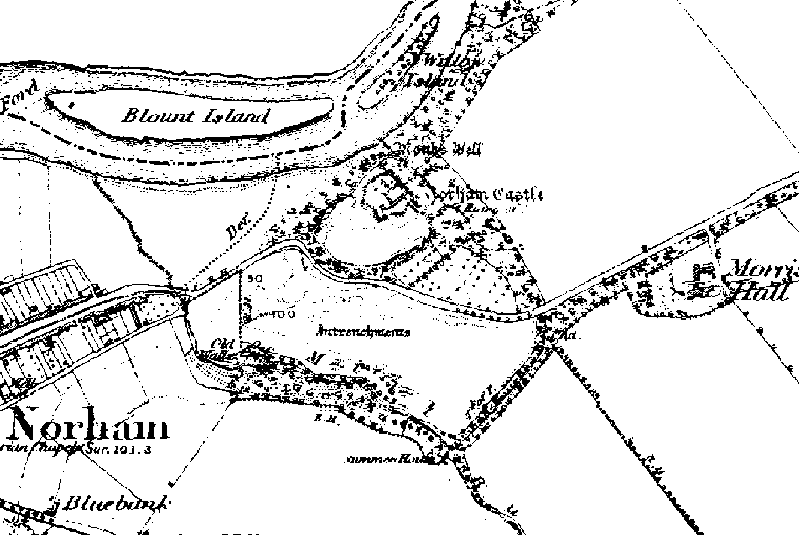

If trouble started brewing with the Picts – or even the intermittent incursions of the Irish from across the sea to the rear – then the tribal leaders might meet at a known location, possibly the Camelot (Caer-maelor) of the legend. ‘Caer-maelor” means, a ‘fort of merchants’, or a ‘trading-post’. Here, they would exchange information, identify a battleground, talk strategies, decided where and when to assemble and deploy their fighting men. And the fighting men, from different tribal groups, would need to readily recognize who their troop leaders might be. Simplicity of recognition would be a necessity. The leaders’ names would have to be understandable to any peasant.

The stone-throwers and slingshots might be assembled under the one called ‘Y Garreg’ – the pebble, and they might be responsible for the opening salvos of the battle. The spear-throwers would be controlled by ‘Y Perisigl’. And their reserves of weaponry supplied to them by ‘Y Gawain’ – ‘the scabbard’. ‘Y Llawnselog’ might ride amongst the fighters stirring up their enthusiasm. ‘Y Galwad’ might call the moves with his Carnyx, or Celtic war-horn. And when everything was set, then the main attack of mounted swordsmen might gallop into the fray led by the bravest of them all, ‘Y Rhuthr’ – the leader of the charge. ‘Y Cau’ – the closer, might be bringing up the rear with the last reserves of warriors, and ‘Y Trist’ – the sad, would not be needed until after the battle to help the wounded and deal with the removal of broken bodies.

Circumstances changed, however, and in the 5th century, the Saxons became the primary enemy.

As the Roman Empire began to collapse, Roman armies retreated to defend Rome from the Barbarians and by 410 AD Britain was abandoned. The string of signalling stations along the Eastern seaboard, known as the Saxon Shore, was left to become derelict. The most northerly fort on a promontory high above the river Tees at Huntcliff, was occupied – casually – by local Celtic families for a while, but they were murdered by emboldened raiding Saxons and their bodies thrown into a nearby well.

The Celts knew that the Saxons (Saeson) were not to be trusted and monitored their activities from the hillside hidden by the trees as they came in ships from the sea and set up camps along the lower reaches of the Tees river, almost on the mudflats. The Celts might have prayed to their gods that a great storm would come in from the North Sea and sweep them all away. The seas had risen almost two feet since ancient times and the Romans had had to retreat to their garrison fort at Catraeth or Cataractonium.

Even though many of the local place names had been given a Latin-sounding equivalent, the Celts knew the area well. A Celtic hillfort was located nearby. The ‘Men of the North’ hadn’t ventured down this far in the days of the Romans because it was the territory of the Brigantes. The Gododdin and the Brigantes would all have had to work together in order to combat the threat from the North Sea. They had to halt the ever-increasing menace. And their countrymen from the kingdom of Rheged brought their men into the fight too.

But when and where did this great battle take place?

Scholars down the years have disputed the location of the battle of Bardon Hill – the last great battle fought between the Celts and the invading Saxons. We know that a decisive battle was indeed fought at Catterick, but did it have Arthurian significance?

Some nit-picking Welsh translations might give us direction.

Firstly, with regard to the River Swale. The derivation of the word ‘Swale’ is given as meaning “fast-flowing” – but this is not enough. The River Swale is indeed fast-flowing, but the similarity between the word ‘Swale’ and word ‘Wales’ cannot be discounted. ‘Wales’ comes from the Old German word ‘Wealas’ meaning ‘stranger, or foreigner’. It is not impossible to imagine that the Saxon intruders settled unimpeded on the flatlands of the Tees river because this land had been abandoned as being unstable by the Celts due to the rising sea-levels in the 2nd– 5th centuries. But as the influx of invaders grew – because their own homelands were being similarly swallowed by the sea – then they would have ventured further inland…until they came across the “foreigners” or ‘wealas’ – Celts, from the river Swale upwards into the hills.

These hills have Arthurian significance.

It is not a small matter that the word ‘Badon’ or ‘Bardon’ has not been assigned a meaning in Welsh. Particularly not when all other Welsh placenames are highly descriptive. Yet a key battle was said to have taken place at Badon Hill which everyone participating in would have to know how to find.

To the Celts, who had no signposts or road maps, people and places could only be found if they were appropriately described. To this day, Jones the butcher, Jones the baker and Jones the candlestick maker would be described as Jones the meat, bread or light. ‘Jones Y Cig’ does not translate as Jones the Butcher, but ‘Jones the meat’…because the simpler form informs a greater number of people who he is, what he does, and where he might be found.

Similarly, with place names. They are designed to enable a stranger to the district to know what to look for. “Pen-y-Bryn”, for instance, is a place name which means ‘the-top-of-the-hill’. “Tal-y-Bont” is a pay-bridge, “Betwy-y-Coed” is a ‘prayer-room in the woods’, “Tan-y-Graig” means ‘under-the-rock’. Places had to be found without signposts in the old days.

It is impossible to imagine that with so many descriptors being employed elsewhere, that the naming of a critical battleground would have been left as a meaningless sound. Badon Hill is not self-explanatory in Celtic-Welsh. Badon has no meaning. Badon, Bardon, Baddon, Mons Badonicus, are just empty noises. It is a hill which has a place in history, but no geographical location.

To retrieve a meaning from it and a place on the map, we would have to imagine how it might have been MIS-spoken or misunderstood by a narrator excitedly telling everyone that a great battle took place at Bardon/ Badon.

In Welsh, a mutation of the initial letter can occur after the word ‘in’, which is either ‘yn’ or ‘ym’ depending on the combination of words. “In Bardon” becomes “Ym Mardon”. “Ym Mardon” can shift in emphasis to become the expression “Yma’r don”, meaning “Here are the waves”. Thus, Bardon becomes a hill from which you can see the waves.

Obviously, with Britain having so much coastline, the number of locations where you can see the waves from a hill are endless. But the fact that it was worthy of particular note as a place where you could see the waves would seem to suggest that it was something of a surprise that you could do so – in the same way as a place called “Kissing Point” might be identified as an especially romantic location to locals, even though it was possible for ‘kissing’ to happen anywhere, anytime.

Bardon – ‘Yma’r don’ – was a special place because it was possible to see the waves of the sea, as might have been spoken in the Brithonic language – which places Bardon in the north as part of the ‘Hen Ogledd’ – ‘Old North’. It would have had significance defensively, since most of the threat in the 5th century came from the sea in the form of the invading Saxons…so the view of the sea would necessarily be on the eastern, not the western, coastline.

Bardon, as a naming word, also had a Latinised version in the form of “Mons Bardonicus”, so that it was of strategic importance to the Romans as well as to the Celtic Britons. But the word would have been originally Celtic since the landscape was there before the Romans arrived. However, Roman buildings in the form of defensive forts would have been originally identified by their Latin names, and the local Celts would have given those names a Celtic flavour.

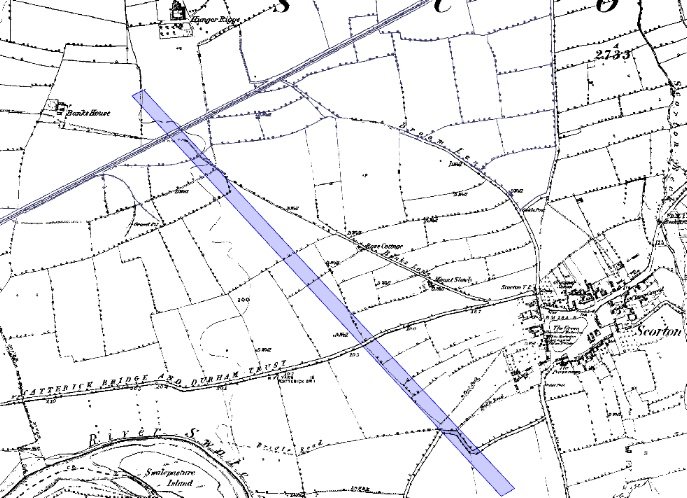

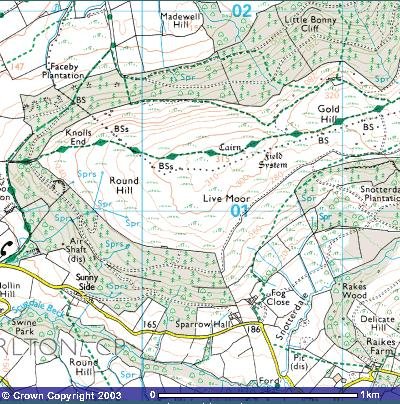

The old Roman fort of Catterick, named ‘Cataractonium’ by the Romans, and Catraeth by the Celts, sits in a most advantageous position defensively. It has the fast-flowing river Swale close by, with its numerous waterfalls – making it highly suitable for the industrialised tanning of leather which was conducted there (Roman army uniforms demanded a constant supply of leather). It sat on top of a small discrete hill, which has a wide stretch of moor on top of it which, to this day, is called “Barden Moor”, and it was at the nexus of a number of Roman roads which radiated out across the inlands of the North.

The territory inland and North had been Celtic for centuries : anything along the eastern shore had already been despoiled by Germanic invaders. The Celts were people of the hills and the rivers; the invaders were people of the sea. The Celts only took action when the encroaching Saxons reached the hills…and Bardon Hill was the targeted hill giving access to the higher grounds beyond.

It is often considered that there might have been two battles of Bardon Hill. The first battle is identified as the last of Arthur’s twelve battles and is dated to have occurred at some time between 500 and 540 AD. 540 AD is a date in history which marks the beginning of a cessation of the massive Saxon invasion. The first battle might therefore be considered to have been a success.

But the second battle of Bardon Hill, conducted in the same Arthurian style, took place in 595 – fifty years after the original battle – was a noble disaster resulting in the rout of the Celtic army and a collapse of the Celts of the North. It was the last time that Celtic battle-tactics were employed, and it marked the end of an age and the disappearance of the Brithonic language from ‘Yr Hen Ogledd’. Somehow the threads of that life and language trickled down to North Wales…fleeing the rear-action assault of the Irish pouring into the Dal Riata region on the western shores as they mauled the remnants of the devastated local inhabitants.

This second Battle of Bardon is the one which Aneurin describes in his epic poem ‘Y Gododdin’.

Aneurin’s poem tries to memorialise the heroic efforts of the “gwyr y Gogledd” in their defence of their homelands at the battle for Catraeth. It gives away numerous subtle clues.

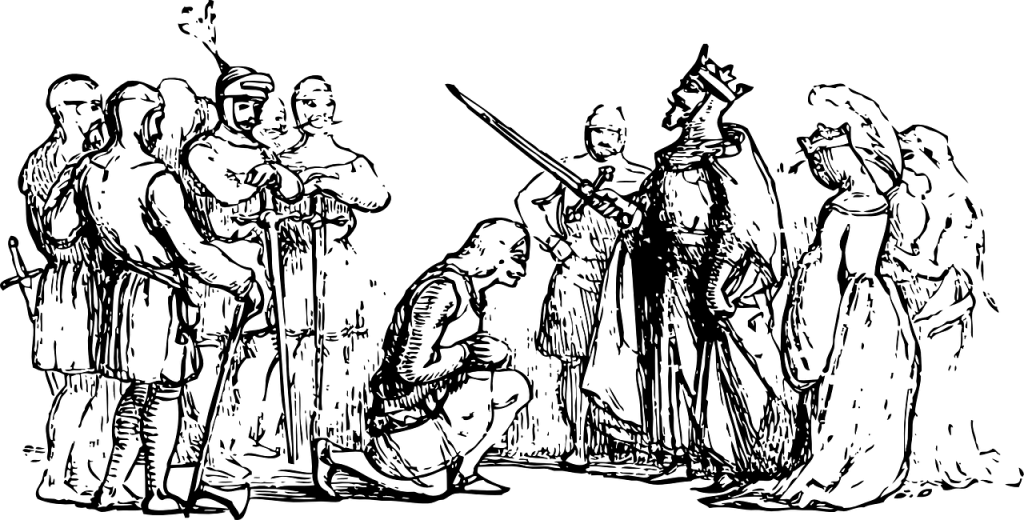

Aneurin does not mention that it was a battle for the fort of Catterick itself, only that the “three hundred” went to Catterick : “gwyr a aeth Catraeth”. Neither does he write of any siege tactics such as attacking a gate or scaling walls. Rather, he writes of men who ‘led a charge’ or participated in a charge. In one case, he writes of a warrior who rode up ‘the slope’. And yet another who was a ‘good caller’. Of another warrior, Aneurin writes that he had his men form a wall – indicating that this warrior was probably the head of a clan and had brought other men with him to the battle. Aneurin uses the word ‘gwr’ (plural – gwyr) meaning ‘men’ to describe the participants in the battle. Actually, the Welsh word for a man is ‘dyn’, “gwr” means ‘husband’. This is significant because ‘husbands’ have the responsibility of wives, children and homes. This gives special meaning to the fact that they were ‘fighting for their lands’.

Most tellingly, Aneurin writes of the ‘three hundred’ that they wore the golden torc. Torcs were only worn by high-order Celtic warriors, which not only designates the three hundred as leaders in charge of other men, but it indicates that there was an effort to maintain a direct connection with the old Celtic way of conducting a battle…a full-out charge by the defenders of the land.

Bardon Hill.

Nennius, Gildas, Aneurin, Taliesin all tried to record great moments in the defence of Prydain, as they knew it. Historians in their way. But they failed to take account of the difference in the kind of information a Celtic peasant farmer and a Romano/British General might need in order to get to the battlefield. A peasant might carry his slingshot across from Carlisle to Catraeth, but a general might need to know the lay-out of the field of action.

Barden Moor would have seen many battles over time which went without notice in the wider world, but the noblest battle of all was fought by the last “Y Rhuthr” – leader of the charge – on a hill where you could see the waves from 30 miles away.

© Janet Williams

(Rough Bibliography)

“When was Wales’” – Gwyn Williams

Y Geiriadur Mawr – 1978 Edition

“Bulfinch’s Mythology”

“Saltburn by the Sea “ – website

“Y Gododdyn by Aneurin” – English Translation by John Williams

Wikipedia

Also – various legends of Arthur in movies, books, magazine articles and websites over a lifetime.

The Nevilles were a powerful family, who held substantial estates and titles, including the Earldom of Westmorland.

The Nevilles were a powerful family, who held substantial estates and titles, including the Earldom of Westmorland.