Chapter 8: The Early Bronze Age and Beyond

The Early Bronze Age spans from about 2,200 BC to 1600 BC and was another period of change. It was during this time that there was the first widespread use of metals.

Whilst there is certainly evidence of continued ritual use of the Henges into and beyond the Early Bronze Age, it is clear that at Thornborough, like elsewhere in Britain, the coming of the Bronze Age brought with it a switch away from the building and use of henges.

The general picture is, however, far from clear. Some henges appear to have been almost abandoned, whilst others were re-modelled in the Bronze Age – usually with the addition of stone circles and avenues.

These changes had a major impact on Thornborough and probably the rest of the Sacred Vale. From the evidence at Thornborough, it is clear that while Henge monuments continued to be the focal point for rituals involving the burial of the dead, they were no longer a place for large scale national pilgrimage.

Curiously, the number of burials at Thornborough appears to increase during the Early Bronze Age. Often, existing burial mounds were re-used for new burials that were inserted into an older Barrow. It is almost as if once the monuments no longer retained the national significance that they saw in the Late Neolithic, that allowed a larger number of people to be buried at the site.

One possible change in practice that may well have had a significant impact on Thornborough was the impact of the discovery of metal on the stone axe trade. At the same time as henges were undergoing this significant change of use, the stone axe trade also seems to have tailed off.

Perhaps the discovery of metal meant that over time the ritual importance of axes was diminished by new metal objects.

Whatever the reason, it is likely that the dramatic reduction in the axe trade will have had a significant impact in terms of both the wealth and the numbers of people passing through Thornborough.

That is not to say Thornborough was completely abandoned. Additional features linked to the henges were constructed during the Bronze Age. This is demonstrated by the building of a large timber post corridor between two Barrows within the henges at Thornborough. The timber corridor is a double alignment of huge parallel timber posts, each leaving a post hole large enough to take a timber more than a meter in diameter. The corridor stretches from Centre Hill barrow, located between the central and southern henges and runs in a south-western direction, passing another barrow located to the west of the southern henge.

The double post corridor is the longest one found so far found in the British Isles, although its full length has not been ascertained, it is at least 350m long, it was created in 1,880 BC and was destroyed by burning in 1,600 BC.

Another interesting aspect of the Centre Hill barrow is the finding of a wooden coffin within it when it was opened up in the 1800s.

The seven henges of the Sacred Vale each have concentrations of barrows associated with them. At

In Thornborough there are at least 15 barrows and probably a great many more hidden in the surrounding landscape.

What is interesting is the way these have been placed within the monument complex and its ritual space.

For example, one barrow was inserted into the bank that formed part of the southern entrance to the centre henge. Similarly, much older Neolithic barrows were re-used with the addition of more burials and a re-cutting of the barrow ditch to create an even larger mound.

Many of the barrows cluster around the henges. They interact with the henges in a way that suggests that the people who built them understood what the henges were for and respected them. Perhaps they saw themselves as continuing an older tradition, but with a new set of rules. There may have been an attempt to gain an association with the ancient ways – a statement that the Bronze Age people now being buried at Thornborough had a lineage that linked with the ancient builders of the henges.

Image: “River Life”, by Joanne.

Image: Over the years, the ritual landscape of the henges acquired a number of monumental constructions. Those that were built of wood are today only visible as crop marks. George Chaplin and Joanne.

The Later Years

After about 1,600 BC, Thornborough appears to have been retained as an important place for the burial of the dead. Much of the evidence that is discussed here is very new, and therefore the exact interpretation is likely to change.

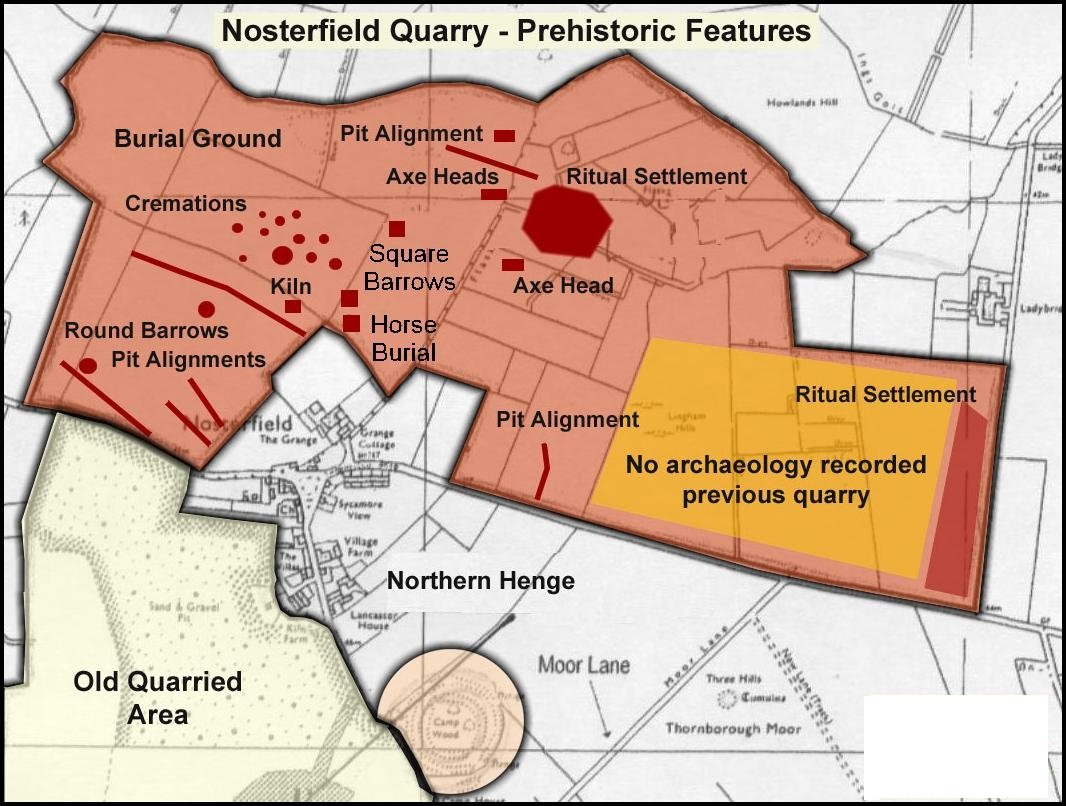

Image: Recent finds on Nosterfield Quarry.

To the north of the Northern Henge, one burial ground discovered during the quarrying of the area may serve as an example as to what was happening elsewhere within the ritual landscape of the henges.

Within the area directly north of Nosterfield Village, a burial group was set up. Although there is evidence of Mesolithic (8,000 years ago) activity in the area, it would appear that the group was first used for burials in the early to middle Bronze Age when three burial mounds were raised.

As time passed, Bronze Age people tended to adopt cremation as part of their burial practices. This change in custom is reflected at the Nosterfield burial grounds, with the internment of 10 or so cremation burials in a loose cluster around the most northerly barrow.

Even though a thousand years had passed since the henges were no longer playing a central role in the religious life of the people of Britain, their significance was still recognized by people living in and around them. Given the henges’ illustrious origins, this is perhaps of no surprise – they remained the largest structure in the region for 3,000 years after their construction.

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of this burial ground is that it was still being used for ritual purposes until the late Iron Age.

Image: One of the square barrows during excavations at Thornborough.

Two square barrows were recently discovered at the Nosterfield burial ground. These probably date to the Iron Age (700BC to 50AD).

Close to one of the square barrows, a ritual deposit was discovered – four horses, two male and two female.

During the Iron Age, the tribe that is generally considered to have controlled this region were The Brigantes, a tribe that controlled most of Yorkshire and a significant part of the modern counties that surround Yorkshire, including Durham, Northumberland and Lancashire.

The Brigantes did not use square barrows, in fact, these two and one other found at Ferrybridge in West Yorkshire are the only examples known within Brigantia. Interestingly, both of these were discovered in 2003.

Square barrows in the north of Britain are unique to a tribe that occupied East Yorkshire called the Parisi. These are famed for their chariot burials, and the tribe tended to bury their leaders in barrows with a square ditch. Within the area defined by the ditch, they placed human remains or horses and chariots. Occasionally, two or all three items were included in the burial. Often we find no remains at all.

This means that even in the Iron Age, the henges were famous enough to be regarded as an important burial place for “foreign” tribal leaders.

The horses have been carbon dated and have been given a date of 50AD, which is a very interesting time for Iron Age Britain. It is the time of the Roman Invasion.

The Romans did not invade the North of Britain until 70AD, so these northern tribes must have been in turmoil at the time that the horses were deposited. Perhaps this ritual was one of special significance – was an attempt to call on the old gods for help, at the same time expressing tribal solidarity against the Roman invaders?

During the Roman period, it is likely that Thornborough and the other henges will have lost a great deal of their ritual significance. The area appears to have moved towards a more functional existence. The only direct evidence of Roman activity at Thornborough is a single Roman kiln and two wells, found in the Nosterfield Quarry. These indicate that the old burial grounds were no longer used as such; the kiln probably indicates some form of local industry site had been built.

However, the monuments of the Swale-Ure plateau have never really been forgotten. During Roman times, there is certainly evidence of at least one visit to the central henge at Thornborough – the result of which was the loss of two brooches in the henge ditch. These were very early Roman brooches, possibly from a time before the Roman invasion of Brigantia, and may be important, During medieval times, the henges at Thornborough were the focus of a festival held by the Marmion family and during the World War II they were used as a munitions dump!

It should be remembered just how unknown the Swale-Ure plateau has been until very recently, and there is probably a lot more to be discovered. Very few people have taken a good hard look at Thornborough so far. There are still many secrets out there.

Image: One of the pit alignments on Nosterfield quarry, this one is most likely Iron Age or later. Dick Lonsdale.

Image: Thornborough Henges. Moth Clark