Image: Thornborough Henges, The Northern Circular.

The one thousand years between 3,000 and 2,000 BC saw the Vale of Mowbray’s most significant period of development. It is at this time that the area between Boroughbridge and Catterick became the Sacred Vale, a premier ritual landscape, with Thornborough as its heart.

To introduce the later Neolithic period across Britain, what people normally think of is a time for the widespread creation of henges. These were the hallmarks of the age; hundreds of Henge monuments were constructed across the length and breadth of the British Isles.

Henges were created by the digging of a circular ditch with one or more sections left undug to form entrances. The earth from the ditch was piled up outside it to create a circular enclosure with an inner ditch, outer earthen wall and one or more

entrances. Wooden posts are also known to have been used in the creation of henges, some having wooden palisades built into the overall design.

These henge monuments are seen as sacred places, religious centres, and the fact that they became so popular is taken as testament to the success of a new religious vigour that spread across Britain during the third millennium BC.

If we compare henge distribution and form to that of today’s religious structures – churches, abbeys, cathedrals etc; It would appear that just like today, a wide variety of sizes were used. The majority of henges were minimal – the equivalent of churches and chapels.

Larger henges could be thought of as small abbeys or large churches. A minimal number of henges were particularly massive and ornate, usually associated with other significant works, and may be regarded as the equivalent of Cathedrals?

There was a religious explosion on the eve of the third millennium BC that brought a dramatic change in monument construction. From the simple cursus type structures created in earlier times, the Neolithic environment was transformed with the creation of more complex and monumental circular henges built in a meticulous manner.

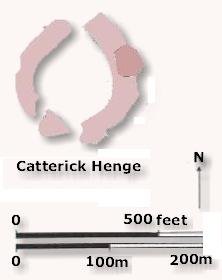

Image: Central Henge at Thornborough. G. Chaplin.

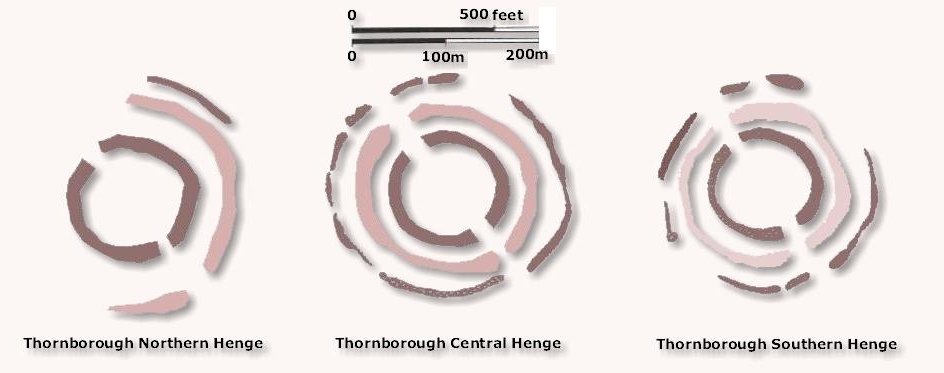

Seven massive henges were built on two linear paths from the Devil’s Arrows. The most northerly line comprising the henges at Hutton Moor, Cana Barn and Catterick (newly discovered). Another line progressed on a more north-westerly path though Nunwick Henge and terminating at the unique triple henge complex at Thornborough.

Each henge in the Sacred Vale is one of the largest henges in Britain. Such a massive operation suggests a long-term and well-organised community structure for the region, one that was able to draw on resources from far outside the locality.

Thanks to the work of Newcastle University, it is Thornborough that is best understood. We will therefore concentrate on this site to explain in more detail the events that were taking effect across the whole landscape of the Sacred Vale.

Image: Central Henge at Thornborough (D. Raven)

For some reason, not only did the form of the monuments themselves change, but also the level of effort spent in their construction was massively increased – There are around 70 cursuses known in Britain, most are fairly similar in size to that at Thornborough. More than 200 henges are known, some, as we shall see were huge. The amount of effort put into building religious structures had increased 100-fold.

Thanks to the work of Newcastle University, it is Thornborough that is best understood, and we will concentrate on this site to explain in more detail the events that were taking effect across the whole landscape of the Sacred Vale.

The Thornborough Henge Complex

Image: Geophysics results for Thornborough Henges, after Harding.

Thornborough is best known for its three henge monuments. It is worth spending some time understanding their significance to the rest of Britain during this period.

There is nowhere else in Britain that has three henge monuments like Thornborough. Not only are they in close and very deliberate alignment, but also they are identical in size and form, a fact that shows not only were they constructed at the same time and by the same people, but when, as happened several times over the hundreds of years they were in use, it was decided to modernise and redefine these monuments, this was done to all the henges in the complex.

At a period when in other areas smaller individual monuments were being constructed and rebuilt, incorporating changes to alignment and construction, Thornborough was redefined during its reconstruction phases. The original alignments and meaning were not being modified – they were being re-stated.

Image: Geophysics results for Thornborough Henges, after Harding.

As if the triple henge monument at Thornborough was not enough, we find that a further three henges, again of identical monumental construction, were built at Cana Barn, Hutton Moor and Nunwick. The one exception to this may be Nunwick, where the apparent lack of an outer ditch suggests that this may have been a later

addition to the complex. It may be that at the same time as the other five henges were being remodelled into the two entrance structures we see today, an additional new henge was created at Nunwick.

The Sacred Vale had somehow acquired a critical importance for the Neolithic peoples of Britain, one which inspired a massive mobilisation of labour for its creation. Subsequent remodelling exercises reaffirmed and renewed this importance. The Sacred Vale was no longer a collection of local spiritual centres. The amount of effort involved in creating this new complex was outstanding for the period – making it possibly the single greatest construction effort in the country.

The same organisational structure that effected the construction of the Sacred Vale monuments in the first place retained its potency for hundreds of years and the monuments at Thornborough retained the same significance and meaning in the Bronze Age.

There is much to suggest that for a significant portion of Britain the Sacred Vale retained a position of unrivalled importance for more than 1,000 years.

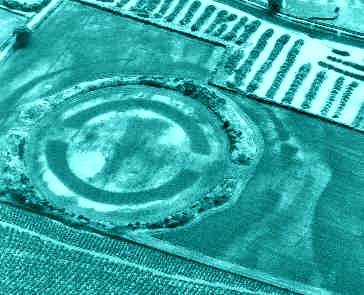

Only one henge in the Vale, does not fit with this uniform henge building, but nonetheless this is usual. The henge at Catterick is smaller than the other six by some 120m. Catterick henge was flattened in antiquity and as a result, only the flimsiest of evidence remains. What is unusual about it is that it appears to lack any ditches and the bank is formed of river worn cobbles.

Only one henge in the Vale, does not fit with this uniform henge building, but nonetheless this is usual. The henge at Catterick is smaller than the other six by some 120m. Catterick henge was flattened in antiquity and as a result, only the flimsiest of evidence remains. What is unusual about it is that it appears to lack any ditches and the bank is formed of river worn cobbles.

This design is mirrored in only one other henge in Britain – Mayburgh Henge at Penrith in Cumbria. The design is also known as “Irish Type” since henges of this manner of construction are better known in Ireland.

This uniqueness tends to suggest that Catterick may pre-date the rest of the henges in the Vale, although like so much about the Neolithic period, this can only be a suggestion.

Image: Geophysical Survey of Catterick Henge.

Thornborough is a unique monument complex, one which stands out against those henges found elsewhere due to its size, the close concentration of these monuments, and their precise alignment. Adding to this the other monuments within the Vale, equally built along precise alignments, and the massive size of the complex compared to the other complexes in Britain, this area is clearly recognisable as one of national importance during the Neolithic period.

More Detail on the Henges

Thanks to Dr Jan Harding’s work, we know that the henges of the Sacred Vale have a particularly long history; these were not a one-off construction, but rather they developed over time. For over a thousand years people were coming to this location and modified the henges, rebuilding them. They created a landscape that throughout the third millennium BC was constantly in use. This gives us a picture of

a continuous process of reinstatement of the ceremonial activities that were happening here.

The story of the development of the henges can be seen when we look at the construction that can be seen today. The current monuments, as has already been stated, consist of two circuits of banks

and ditches. It is unlikely that both these circuits were constructed at the same time. They were the product of two distinct phases of activity.

Firstly, the outer bank and ditch were built. This represented the largest henges constructed in the plateau. The inner ditch for these henges is seen today in what we recognise as the outer ditch for the current henges. In this original phase of construction, a segmented ditch was built, surrounded by an outer bank. The segmented ditch had at least five entrances around its perimeter, this is very reminiscent of earlier, pre-henge monuments that were constructed within the British Isles.

This suggestion of an earlier phase of construction was confirmed by Dr Jan Harding during excavations at the henges in the 1990s. These excavations suggested that this first phase of construction was not a single act in itself, but rather it was the result of several construction periods that may have been the outcome of generations of work at the henges.

During the excavation of the henges, several phases of construction were noted. Initially, a fairly unremarkable outer bank was created by the digging of a shallow ditch .5m deep. The earth from this ditch was piled up outside to create the outer bank. At a later time, the ditch was re-dug, with the soil that was dug out being used to enlarge the bank. In addition, was built a palisade fence along the inside edge of the bank; in short the monument had been renewed. This activity possibly occurred from 3,100 to 2,800 BC.

After 2,800 BC, the monuments in the Sacred Vale underwent a remarkable event. People were not content with the six giant ceremonial monuments (five if we assume Nunwick did not exist at this time). They decided totally to reconstruct all the henges in this massive complex. Not only was this to be a restatement of the rituals that were performed at the complex, but it was also a statement of increased power. As monumental as the original henges were, they were inadequate and needed to be made even more significant – an impressive statement of the continued potency of the religion that brought them about.

After 2,800 BC, the monuments in the Sacred Vale underwent a remarkable event. People were not content with the six giant ceremonial monuments (five if we assume Nunwick did not exist at this time). They decided totally to reconstruct all the henges in this massive complex. Not only was this to be a restatement of the rituals that were performed at the complex, but it was also a statement of increased power. As monumental as the original henges were, they were inadequate and needed to be made even more significant – an impressive statement of the continued potency of the religion that brought them about.

Image: An early phase henge at Thornborough. Joanne.

They went back to the original monuments and created a new monument within each – the inner ditch and bank were constructed.

The inner ditch and bank were very much larger and imposing than the original monument structure. The new ditch was approximately 16m in width and more than 2.0m in depth, this was a substantial and giant earth-working exercise and represented the largest amount of effort in the creation of monuments anywhere in Britain for the period – spread across six of the largest henges in Britain in a single act. This was also reflected when it came to the construction of the new inner bank; even today it survives on a massive scale, 16-18m across. It is difficult to calculate the original height, but it would have been at least 4 metres high and perhaps much larger.

These Earthworks would have required a substantial amount of effort, this effort being co-ordinated across a wide geography covering the six monuments within the Sacred Vale. They were radically different to what had been seen before, yet this was a restatement of the henges’ original purpose. This new phase of work created enormous monumental structures that isolated the interior space from the outside world.

Unlike earlier monuments, these new monuments closed off the surrounding landscape. The effect of the huge earth wall that surrounded the internal area created monuments that sat within the landscape but were not part of it. This isolation was emphasised by a dramatic reduction in the number of entrances to the monument, unlike the earlier structures, that had five or more entrances, these new monuments had just two.

To emphasise this rigid control over access to the monuments, excavations at Thornborough’s southern henge revealed that a structure using wooden posts was used to create some form of entrance control point. This indicates that entrance to the henges was formally orchestrated.

To emphasise this rigid control over access to the monuments, excavations at Thornborough’s southern henge revealed that a structure using wooden posts was used to create some form of entrance control point. This indicates that entrance to the henges was formally orchestrated.

This suggests that there were controls placed on those entering the sacred space of the henge and that the environment within the henge was designed to exclude the outside world from those that observed the rituals within.

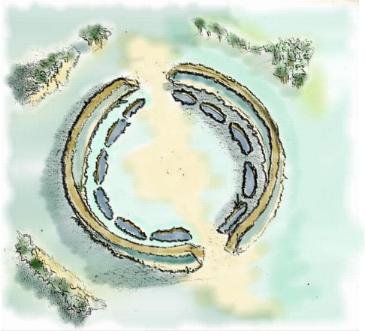

Image: Thornborough central henge, English Heritage.

One of the intriguing aspects of Thornborough is whenever a new phase of building takes place, no matter how radical it was, people always paid respect to their past. New developments of the henge structure observed and perhaps emphasised earlier features.

This tells a story of the continuation of the function and purpose of the henges within a strengthening religious society whilst the work of earlier ancestors was not

forgotten. This can be obviously seen in the layout of the henges; as has been discussed, the new monuments built around 2,800BC were built within the centre of

the older henge monument – this paid reference to prior heritage by effectively renewing an older site. The two entrances, for example, sit in line with the earlier entrances of the first henge.

It should also be noted that the central henge was built on top of the earlier cursus monument – referencing a site that was 500 or more years earlier.

It should also be noted that the central henge was built on top of the earlier cursus monument – referencing a site that was 500 or more years earlier.

By the time the henge was built, the cursus would have been silted up, it would have been very difficult to see, but it was clearly known about. The site, and its importance would have been passed down from generation to generation so that when the time came to build the henges, the earlier monument could be referenced so accurately.

Image: Thornborough central henge, final stage of construction. Joanne.

The overlaying of the henge on the cursus was in no way an accident, the northern ditch of the cursus runs directly across the southern entrance of the central henge. The other cursus ditch runs right along the other side of the henge entrance.

The Neolithic temple builders at Thornborough clearly drew on their past to make a statement of continuity, the type of monument built had changed but it still referenced the earliest monument at the site.

Image: The Devil’s Arrows at Boroughbridge, George Chaplin.

Image: Orion over Thornborough, Joanne.

Thornborough – The Orion Complex?

To add to the theme of continuity of practice, the new monuments at Thornborough referred back to some of the astronomical elements that had been identified by the earlier enclosures. Work carried out by Newcastle University has suggested that the entrances to the henges have a shared axis that references astronomical events. The standstill of the lunar cycle is referenced, as well as framing Orion at its highest point during the period when it was visible.

To add to the theme of continuity of practice, the new monuments at Thornborough referred back to some of the astronomical elements that had been identified by the earlier enclosures. Work carried out by Newcastle University has suggested that the entrances to the henges have a shared axis that references astronomical events. The standstill of the lunar cycle is referenced, as well as framing Orion at its highest point during the period when it was visible.

It is also possible that the layout of the three henges at Thornborough was a deliberate attempt to represent the three stars that form the main belt of the constellation of Orion. If this is so, then it is represented as a mirror image of Orion’s Belt and is similar to the alignment of the Great Pyramids of Giza constructed some 1,000 years later.

Some of these astronomical alignments may appear to be far-fetched and only further work will be able to confirm the truth of the matter.

Image: Orion, Giza and Thornborough. Nigel Swift.

However, it should be asserted that the actual alignment of the henges and other features was of definite importance regarding the rituals and ceremonies that were taking place within.

On entering a henge, the first thing that is striking is how they enclose the immediate space, excluding the surrounding landscape and focusing the attention upwards in the direction of the entrance openings.

It is important to note that the banks would have originally been much larger than they are now, and that the effect of the wide inner ditch will have been to reduce the “people space” within the henge, so that people clustered in the centre of the henge. This would have concentrated the attention of the attendees on the alignment of the entrances. In effect, the participants became part of the alignment.

Image: The Orion Constellation.

Glowing White Temples

The bank of the central henge may have been originally coated in gypsum. This idea was brought about due to the finding of gypsum deposits at the base of the bank during excavations in the 1950s and re-enforced by the finding of a gypsum-filled ditch close to the southern henge.

Gypsum is not found in the area of the henges and will have been transported to the henges, a costly task given the already substantial investment in the earthworks in terms of manpower.

Gypsum is the major constituent in wall plaster, and it is therefore possible that during the later Neolithic period, gypsum paste was spread on the banks of the henges to create massive white walls.

This gypsum coating would have had the effect of reflecting sun and moonlight, suggesting that the henges would have had a shimmering visual effect.

Gypsum, however, does not last long in the open since it is water-soluble. The recent identification of a gypsum pit close to the southern henge at Thornborough by Newcastle University suggests that this may have been a maintenance store for use in periodic refurbishment of the henges’ shimmering coat.

Image: Crop Circle at Thornborough May 1st 2003.

If the walls of the henges were “plastered”, we should not forget that they might not have been left white. It is possible that they may have been painted with pigments, although to date, there is no evidence of this.

The construction of the henges, with their massive walls – pasted with white gypsum, created within them a wholly unnatural space, isolated from the outside world and surrounded by a brilliant white wall. At night, the only visible features outside the henges would have been the astral bodies, which themselves were referenced within the construction and alignment of the monuments themselves.

What is seen at Thornborough and across the Sacred Vale during the Neolithic period is a protracted series of developments that further refine the themes defined within the earlier structures. Over time the works became increasingly monumental, taking more effort as the site became more popular and ultimately creating a truly extensive monument complex.

The earlier constructions referenced astral bodies that may have been a focus for worship, perhaps being seen as gods. The later monuments were transformed into not just points of reverence, but perhaps also becoming an earthly home for these gods, a place where the outside world is excluded so that the unnatural inner world of the henge could allow total concentration on the ceremony held within.

Image: Central Henge at Thornborough, George Chaplin.