Contents

- 1 Introduction to the European Ice Age

- 2 Planet Under Ice — The Consequences of a Colder World

- 3 Zoning the Chill — A Spectrum of Glacial Harshness

- 4 Human Chronology Overlay — Reconciling Regional Periodisations

- 5 Glossary & Tooltip Index (v 1.1)

- 6 Periods Reference Sheet

Introduction to the European Ice Age

What Is an “Ice Age”?

What Is an “Ice Age”?

In geological terms an Ice Age is a multi‑million‑year interval during which permanent ice sheets persist at one or both poles. Within an ice age the climate oscillates between cold glacial stages—when ice expands far from its cores—and warmer interglacials like our present Holocene. We live inside the Quaternary Ice Age (2.6 Ma–present); the “Last Ice Age” that concerns archaeology is the most recent glacial cycle of this longer icy era.

A Brief History of Ice Ages on Earth

| Geological era | Major ice ages | Key drivers |

| 2.4–2.1 Ga | Huronian | Rising oxygen + continental positions |

| 720–635 Ma | Cryogenian (“Snowball Earth”) | Albedo feedback during Rodinia breakup |

| 450–420 Ma | Late Ordovician–Silurian | Gondwana at the South Pole + CO₂ draw‑down |

| 360–260 Ma | Carboniferous–Permian | Mountain uplift, coal swamp carbon burial |

| 34 Ma–present | Cenozoic / Quaternary | Antarctic isolation, Himalayan uplift, orbital forcing |

Within the Quaternary at least 11 full glacial–interglacial cycles are recognised, paced by Milanković orbital parameters (eccentricity 100 ka, obliquity 41 ka, precession 23 ka) that modulate high‑latitude summer insolation.

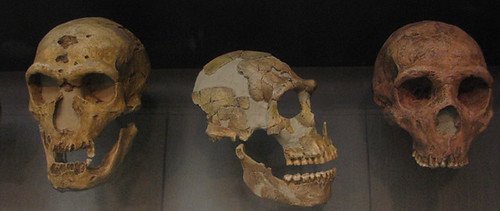

Human Storylines in Ice‑Age Europe

- Early hominins (Homo antecessor at Atapuerca > 1 Ma) arrived during a temperate window.

- Neanderthals survived multiple glacial periods but retreated to southern refugia by the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM).

- Homo sapiens entered c. 45 ka, endured MIS‑3 climatic whiplash, then recolonised deglaciated Northern Europe after 15 ka.

- Each cold phase fragmented habitat and opened or closed migration corridors—a framework vital to our Brigantian questions.

The Last Glacial Cycle in Europe (115 ka – 11.7 ka)

| Chronology | Climate marker | Ice‑sheet extent | Cultural frameworks |

| 115–71 ka (MIS‑5d‑a) | Early Weichselian stadials/interstadials | Scandinavian ice grows; Britain mostly ice‑free | Late Neanderthal industries |

| 71–29 ka (MIS‑4 & MIS‑3) | Dansgaard–Oeschger oscillations | Scottish & Alpine glaciers wax/wane | Mousterian → Aurignacian → Gravettian |

| 29–19 ka (MIS‑2) | Last Glacial Maximum | British–Irish + Fennoscandian ice coalesce; Channel dry | Solutrean, Hamburgian |

| 19–14.7 ka | Heinrich‑1; initial melt | Doggerland tundra thaw | Badegoulian → Early Magdalenian |

| 14.7–12.9 ka | Bølling–Allerød warmth | Rapid retreat; N. Sea plain habitable | Magdalenian/Azilian northward surge |

| 12.9–11.7 ka | Younger Dryas | Scottish & Scandinavian readvance | Federmesser, Swiderian |

| 11.7 ka–present | Holocene | Ice residual in Scandinavia | Mesolithic, Neolithic expansions |

West‑to‑Baltic Spatial Synopsis

West‑to‑Baltic Spatial Synopsis

- Atlantic façade: Ice limited to upland Ireland/Brittany; milder oceanicity sustained refugia.

- Western Britain: Welsh & Cumbrian glaciers fed an Irish‑Sea ice lobe; retreat formed proglacial lakes and east‑coast routes.

- North‑Sea Plain: Periglacial Doggerland linked Britain to Continent until c. 8 ka.

- Central Europe & Baltic: Scandinavian ice carved Moraines south of Berlin–Warsaw; meltwaters birthed Oder & Vistula.

- Alpine & Carpathians: Glacier tongues dammed lakes; Danube corridor remained a key east–west passage.

Why This Matters for Our Programme

- Migration Gateways – Timing of the Atlantic, Doggerland and Danubian corridors underpins models for Brigantian and other tribal movements.

- Population Bottlenecks – Genetic Drift in refugia helps explain later Iron‑Age tribal discontinuities.

- Technological Pulses – Cold‑phase compression followed by warming often coincides with innovations (microliths, archery).

Forthcoming country chapters will layer this glacial template onto local pollen, sea‑level and archaeological datasets—from Galicia’s bays to the Baltic morainic arcs—building a high‑resolution atlas of human resilience and mobility across Ice‑Age Europe.

<H3 data-pm-slice="1 1 []">How Do Ice Ages Form—and Where Do Ice Sheets Grow? The Cooling Mechanisms

The Cooling Mechanisms

- Orbital (Milanković) Cycles – Quasi‑periodic variations in Earth’s orbit change summer solar input at high latitudes. If boreal summers grow too cool, winter snow survives and the high‑albedo surface reflects more sunlight, amplifying the chill.

- Greenhouse‑Gas Dips – Long‑term tectonic or biological sequestration of CO₂/CH₄ thins the atmospheric “duvet,” letting more heat radiate to space.

- Tectonic & Oceanic Rearrangements – Continental drift can place land over poles (permitting vast ice sheets) or reroute warm currents (e.g., closure of Central American Seaway strengthened Atlantic meridional overturning and intensified high‑latitude snowfall).

- Volcanic & Dust Feedbacks – Major eruptions and continental‑scale dust storms boost stratospheric aerosols, shading the planet and nurturing further snowpack.

Geographic Controls on Ice Distribution

| Factor | Effect | European expression |

| Latitude | Low summer sun northward of 60 ° N favours year‑round snow | Fennoscandian & British‑Irish domes nucleated above 60 ° N and radiated outward |

| Altitude | Cooler air aloft lowers the Equilibrium Line Altitude (ELA) | Alps, Pyrenees and Scottish Highlands held valley glaciers even at 45–57 ° N |

| Continentality | Interior regions with low winter humidity may remain ice‑free despite cold | Eastern European Plain south of Moscow saw patchy Loess but little ice |

| Proximity to Moisture | Maritime areas with heavy snowfall build thick ice despite milder temps | Norwegian Atlantic façade and western Scotland developed extensive névé zones |

Thus, ice thickness declines equator‑ward, but high‑relief coastal zones can rival polar deposits, while dry continental basins may remain periglacial rather than glaciated.

Planet Under Ice — The Consequences of a Colder World

Planet Under Ice — The Consequences of a Colder World

Geological Transformation

| Process | Resulting landforms | Examples across West‑to‑Baltic Europe |

| Glacial Erosion | U‑shaped valleys, fjords, corries | Hardangerfjord (Norway), Glencoe (Scotland), Val d’Anniviers (Alps) |

| Abrasion & Plucking | Striated bedrock, roche moutonnées | Lake District scarps, Bohuslän archipelago |

| Deposition | Moraines, Drumlins, eskers, till plains | Yorkshire Vale Drumlin swarm, Saalian push moraines in Poland |

| Isostatic rebound | Raised beaches, marine terraces | Scotland’s “Parallel Roads” of Glen Roy; Baltic Sea strandlines |

| Meltwater Megafloods | Outburst channels, loess blankets | Channel River spillway (Channel Isles), Pripet Marsh silt fans |

Glaciation therefore creates topographic diversity and redirects drainage: proglacial lakes dammed by ice and debris can breach, carving spillways that later guide human routeways (e.g., Tyne–Solway gap; Øresund).

Impact on Ecosystems & Resources

| Domain | Ice‑age response | Knock‑on effects |

| Flora | Boreal steppe‑tundra replaced temperate forest north of ~47 ° N; refugia persisted in Iberia, Italy, Balkans | Source areas for post‑glacial tree recolonisation; today’s genetic hotspots (e.g., Iberian oaks) |

| Fauna | Mammoth, reindeer, saiga antelope expanded; temperate megafauna retreated | Mobile hunter bands tracked herds across mammoth‑steppe; bone for tools & dwellings |

| Coastlines & Seas | Sea‑level fell 120 m; continental shelves exposed (Doggerland, Biscay Plain) | New hunting grounds; flint sources (North‑Sea chalk) accessible; later drowned sites challenge archaeology |

| Hydrology | Permafrost limited infiltration; braided rivers carried high sediment loads | Widespread loess deposition = fertile Holocene loam belts (Northern France, German Lösshügelland) |

| Minerals | Glacial till mixed erratics; esker gravels became post‑glacial aggregate resources | Scandinavia & Britain exploit sand‑gravel from meltwater deposits; placer gold redistributed in Alps |

Human Adaptive Solutions

Human Adaptive Solutions

| Challenge | Adaptive response | Archaeological signature |

| Extreme cold & wind | Tailored clothing (fur, sinew stitching), semi‑subterranean dwellings | Eyed bone needles at Kostenki & Creswell Crags; mammoth‑bone huts in Ukraine |

| Resource seasonality | High mobility; logistical forays; reindeer drive lanes | Reindeer bone concentrations at Ahrensburg sites; engraved route plaques |

| Nutritional stress | Broadened diet (marine mammals, fish, plant storage) | Fishhooks/harpoons (Tarnheuvel); lipid residues in Solutrean shells |

| Navigation of new terrains | Portable mapping (Patrick‑bones, baton‑perforé motifs) | Possible landscape engravings on plaquettes from Les Varines, Jersey |

| Social risk | Long‑distance exchange networks for exogamy & obsidian/flint | Exotic raw‑material sourcing >300 km (Solutrean Corbières flint at Montlleó) |

| Technological leaps | Pressure‑flaking microblades, atlatl, bow | Early bow fragments in Holmegård, Denmark; Solutrean laurel‑leaf bifaces |

From Survival to Flourishing

Despite harsh climates, population rebounds after 20 ka show successful adaptation. Art (Lascaux, Altamira), complex burial rites (Sunghir), and large aggregation sites (Pavlov) testify that culture flowered, not merely endured. These technological and social innovations laid foundations for Mesolithic exploitation of post‑glacial environments—and for later tribal identities such as the Brigantes.

Upcoming chapters will unpack these adaptive strategy’s region‑by‑region, tracing how glacial legacies shaped ecological niches, resource frontiers, and the cultural mosaics into which our target populations emerged.

Zoning the Chill — A Spectrum of Glacial Harshness

We can now introduce the idea of glacial “zones” of harshness – we need to try to map a spectrum of zones of harshness over time, and covering the land and sea masses of Europe. We would need to understand how the local geography, nature, and humanity would respond to that. For example, hardness of rock, direction of existing valleys, Solar variances, altitude, etc. We can mention our core timeline of interest is from the Palaeolithic period onwards.

Concept of “Harshness Zones”

Rather than a single snow‑line, a European ice age generated concentric or patchy bands of severity determined by latitude, altitude, bedrock, oceanicity and solar aspect. Each zone imposed distinctive constraints and opportunities on landscapes, ecosystems and humans.

| Zone label | Typical LGM climate | Key physical drivers | Representative terrain | Biotic & human implications |

| Core Ice‑Dome | Permanent ice cap, ‑30 °C mean annual | High latitude/altitude; positive mass balance | Scandinavian shield, Ben Nevis plateau | Uninhabitable; glacial scouring creates raw mineral surfaces for post‑glacial soils |

| Polar Desert | Sparse snow, fierce katabatic winds, permafrost | Rain‑shadow lee of domes; low moisture | Doggerland interior, southern North Sea plain | Patchy steppe; limited wood; humans visit seasonally for reindeer drives |

| Periglacial Steppe | Long winters < ‑15 °C; brief 10 °C summer | Distance from westerlies; loess deposition | Hungarian Plain margins, Champagne chalklands | Rich grazing → mammoth/reindeer herds; seasonally mobile hunters |

| Montane Valley Glaciation | Glacier tongues fill troughs; refugia on sunny slopes | Altitude + orographic snow | Alps, Pyrenees, Scottish Highlands | Ecological “islands” for endemics; humans exploit rock‑shelters above ice |

| Temperate Refugia | Mean annual > 5 °C; mixed forest pockets | Low latitude, maritime influence, rain‑shadow | Cantabrian coast, Rhône corridor, Po valley | Continuous human occupation; seed banks for post‑glacial biota |

| Maritime Shelf Fringe | Ice‑free but cold; high nutrient upwelling | Gulf Stream eddies, tidal mixing | Brittany headlands, Irish west coast | Durable shellfish larders; coastal foragers innovate fishhooks |

Temporal Shifts of Harshness Bands

- Bølling–Allerød (14.7–12.9 ka): Polar desert retracts to Baltic rim; temperate refugia expand north of 50 °N. Hunter networks fuse, fostering Magdalenian art fluorescence.

- Younger Dryas (12.9–11.7 ka): Bands snap southward ~500 km within decades. Human groups contract to Atlantic façade and Carpathian foothills; techno‑systems simplify (Federmesser).

- Early Holocene (11.7–8 ka): Core ice retreats to Scandinavia; periglacial steppe replaced by birch–pine parkland; maritime shelf fringe drowns (Doggerland diaspora).

“Harshness Modifiers” — Local Factors

| Modifier | Amplifies or buffers cold? | Illustration |

| Rock Hardness | Tough gneiss/granite resists scour, leaving high Tors; soft chalk erodes into dry valleys | Granite tors of Bodmin Moor remained nunataks above valley ice |

| Valley Orientation | Troughs aligned to ice flow funnel glaciers; transverse valleys form lee refugia | East–west Welsh valleys glaciated deeply; north‑facing side‑glen at Cwm Idwal held early post‑glacial flora |

| Solar Aspect | South‑facing slopes melt snow faster, supporting steppe ‘islands’ | South Pyrenean faces hosted juniper scrub 3 ka earlier than north side |

| Bedrock Permeability | Karst drained meltwater, limiting ice adhesion; impermeable clay basins built thick till | Yorkshire Limestone scarps kept thin patchy ice yet offered cave shelters |

| Continentality | Interiors lacked snowfall, moderating ice build; coasts got heavy snow but warmer winters | East Baltic interior periglacial dune fields vs. Norwegian fjord full‑thickness ice |

| Ocean Current Variability | North Atlantic meltwater pulses stalled AMOC, deepening chill on NW Europe | Heinrich‑1 outburst 17 ka thickened Irish Sea lobe |

Implications for Our Research Agenda

- Route Viability Modelling – Incorporate zone maps into least‑cost path models for Late‑Glacial migrations.

- Refugium Genetics – Target aDNA sampling in refugia pockets (Cantabria, Garonne, Alps) to capture founder lineages.

- Geo‑archaeological Coring – Multi‑proxy lake cores at zone margins track biotic turnover and human signal intensity.

- Rock Shelter Survey Bias – Recognise survey gaps in lee‑side refugia valleys that may hide continuous occupation sequences crucial for understanding Brigantian origins.

Mapping harshness spectra through time converts “ice maps” into dynamic habitat and mobility surfaces—essential for reconstructing how ancestors navigated, settled, and eventually formed the confederations we now seek to trace.

Mapping Erosion Intensity vs. Local Geology

To operationalise these zones we propose a geo‑morpho‑lithic overlay: plotting characteristic glacial landforms against a resistance index for underlying bedrock and regolith. This cross‑comparison helps grade landscapes by impact severity—from “scoured raw” to “lightly frost‑shattered.”

| Data layer | Metric / proxy | Why it matters | Example application |

| Landform inventory | Digital mapping of drumlins, roches moutonnées, meltwater channels, block‑fields | The density and scale of erosion/deposition features mirror the mechanical power of the ice | Yorkshire drumlin swarm vs. Baltic push‑moraine arcs reveal differing basal stress |

| Lithological resistance | Rock strength classes (UCS, fracture density), weathering index | Hard rocks (granite, gneiss) yield dramatic whalebacks; weak mudstones become streamlined low drumlins | Compare Scottish Benbulben sandstone benches with Norwegian gneiss trough‑walls |

| Thermo‑dynamic regime | Modelling freeze–thaw cycles, permafrost depth | In temperate margins sub‑glacial meltwater and seasonal frost drive quarry‑like fragmentation | Periglacial tors on Dartmoor vs. polish on Scandinavian shield |

| Slope & aspect | DEM‑derived insolation and stress fields | South‑facing slopes in mid‑latitudes thaw faster, enhancing block‑field creep rather than abrasion | Asymmetric valley profiles in Pyrenees record sun‑exposed debris fans |

| Palaeo‑ice dynamics | Flow velocity reconstructions from lineations | Faster ice = more abrasive power where bedrock permits | Irish Sea lobe lineations tie to soft Carboniferous Shales |

Temperate vs. Polar Hardness Paradigm

- In temperate zones (ELA near valley floor) freeze–thaw and pressurised meltwater exploit joints, producing block‑fields, tors and erratic spreads—erosion is piecemeal but pervasive.

- In polar or cold‑based zones the glacier is frozen to its bed: mechanical erosion is minimal, yet plucking at warm‑based lobes’ margins sculpts sharp knolls. Thus some hard rocks (Finnmark gneiss) emerge almost unscathed, whereas adjacent warm‑based corridors (Troms mica‑schist) are deeply gouged.

Deliverables

- Resistance‑weighted Erosion Map – 1 km raster combining landform scores with lithology classes across western–Baltic transect.

- Harshness Zonation v1.0 – Five ordinal bands (Extreme, High, Moderate, Low, Minimal) feeding into route‑cost models for human dispersal.

- Validation Points – Cosmogenic‑nuclide ages on polished surfaces vs. block‑field mantles to calibrate model.

This integrated approach allows us to refine “harshness” from a simple climatic label into a quantifiable landscape stress index—crucial for testing whether migration corridors align with less‑eroded, resource‑richer tracts or with glacially scoured but topographically open pathways.

Natural‐Element “Fingerprints” — Fine‑Tuning Harshness with Local Proxies

While the continental‑scale harshness model provides broad bands, micro‑scale surveys reveal subtle gradations that only emerge when we layer in specific natural elements preserved in well‑studied landscapes. These proxies help us calibrate zone boundaries and reconstruct human/nature interactions with greater nuance, especially in regions where the artefactual record is thin.

| Proxy class | What it records | Data sources & survey examples | How it refines the model |

| Erratic lithology mosaics | Basal entrainment paths & transport energy | Petrological census in the Lake District (UK), Baltic Archipelago project | Determines former ice‑flow corridors and shear‑zone intensity within “High” vs. “Extreme” zones |

| Frost‑heave patterned ground | Seasonal freeze–thaw amplitude | High‑resolution UAV Photogrammetry on the Cantabrian plateau | Separates temperate periglacial margins from polar desert plateaus within “Moderate” zone |

| Ice‑wedge pseudomorphs | Depth of permafrost cracking | Trench logs in Netherlands polder soils; Polish loess sequences | Marks southward limit of continuous permafrost during Younger Dryas |

| Speleothem hiatus layers | Periods of cave desiccation during cold phases | U/Th‑dated stalagmites in French Pyrenees; Peak District (UK) | Pinpoints moisture collapse belts inside mountain rain‑shadows |

| Palaeolake varves & tephras | Meltwater pulse chronology & volcanic dust flux | Nar Gölü Varve core (Turkey) used as template; proposed coring at Llangorse Lake (Wales) | Synchronises harshness jumps (e.g., H1, YD) across regions |

| Macrofossil refugia (yew, juniper) | Micro‑climatic “oases” within otherwise severe belts | Genetic outlier stands in Saxon Switzerland & Glen Affric | Highlights potential human hunting stations or winter camps |

Workflow for Integrating Proxies

- Select Exemplar Landscapes with dense geomorphic mapping (e.g., Cairngorms, Harz Mountains, Šumava).

- Digitise & Attribute each proxy in a multi‑layer GIS; assign confidence scores.

- Statistical Downscaling from proxy clusters to 1 km² probability rasters, feeding into the resistance‑weighted erosion map (Section 4.5).

- Human‐Landscape Overlay – Intersect updated harshness surface with known Palaeolithic/Mesolithic site catchments to test settlement preferences.

By anchoring broad climatic belts to tangible field evidence, we sharpen predictions about where undiscovered sites may lie and about the lived experience—from glacial grind‑zones that offered little but stone, to lee‑side refuges where plants, animals and ultimately people endured.

Human Chronology Overlay — Reconciling Regional Periodisations

Archaeological periods rarely start and finish on the same calendar dates across Europe. Each nation (and often each research tradition within a nation) anchors its Palaeolithic–Iron‑Age ladder to local “type” discoveries. For early prehistory those anchor dates are frequently exported wholesale to neighbouring regions where the underlying data are thinner. To build a continent‑wide human overlay that can interact meaningfully with our glacial‑harshness and erosion models, we must first acknowledge this chronological patchwork and then propose a harmonised, editable framework.

Indicative National/Regional Date Ranges

| Macro‑region | Lower Palaeolithic start | Upper Palaeolithic | Mesolithic | Neolithic | Bronze Age | Iron Age – La Tène peak |

| Iberia | > 1 Ma (Atapuerca) | 40–11.7 ka | 11.7–6.0 ka | 5.6–2.5 ka | 2.2–0.8 ka | 0.8 ka → Roman (c. 200 BC) |

| France | 1.0 Ma | 42–12.7 ka | 11.5–5.5 ka | 5.4–2.0 ka | 2.0–0.8 ka | 0.8–0.05 ka (La Tène D 200 BC–AD 50) |

| Britain & Ireland | 0.8 Ma | 38–11.6 ka | 11.6–4.0 ka | 4.0–2.5 ka | 2.5–0.8 ka | 0.8–0.05 ka |

| Germany/Central EU | 0.6 Ma | 40–12.9 ka | 12.9–5.5 ka | 5.5–2.2 ka | 2.2–0.8 ka | Hallstatt/La Tène 0.8–0.05 ka |

| Scandinavia | 0 Ma (no Lower Pal) | 14–11.7 ka | 11.7–4.0 ka | 4.0–2.4 ka | 2.4–0.5 ka | 0.5 ka → Roman Iron Age (AD 0–400) |

| Baltic States | – | 13–11.7 ka | 11.7–4.8 ka | 4.8–2.1 ka | 2.1–0.5 ka | 0.5–0.05 ka |

Dates rounded; AH = Ante Holocene; Ka = thousand calendar years before present.

Why Divergence Occurs

- Type‑Site Anchoring – e.g., French Aurignacian defined at Chauvet pushed the “Upper Palaeolithic start” earlier there than in Scandinavia, where human presence began later.

- Research Intensity Bias – High‑resolution Mediterranean seafront sequences drive finer Mesolithic/Neolithic slicing than, say, Baltic lake margins.

- Methodological Updates – AMS dating revisions move period boundaries in step with laboratory advances (e.g., British Early Neolithic now often starts c. 4000 BC vs. 4500 BC pre‑2000).

- Cultural vs. Economic Criteria – Ireland defines Iron Age partly by the arrival of ring‑forts and rotary querns; Germany by La Tène metalwork; Iberia by Mediterranean colonisation horizons.

Constructing the Initial Overlay

- Adopt Broad “Envelope” Bands – We take the widest start and end dates per macro‑period across western‑to‑Baltic Europe to ensure inclusive coverage.

- Assign Confidence Scores – Regions with dozens of radiocarbon series (e.g., France, Britain) receive high confidence; under‑sampled areas (e.g., Doggerland offshore sites) remain provisional.

- Overlay with Harshness Zones – The initial period envelopes are intersected with the harshness raster (Section 4) to model potential spatial/temporal occupation windows.

- Flag Discordances – Where a period’s envelope overlaps an “Extreme” harshness zone with no known sites, we mark it for targeted survey or for potential down‑dating of local chronologies.

Path for Future Refinement

- Dynamic Database – Every new secure 14C, OSL or aDNA date uploads to a cloud GIS and triggers automated recalculation of regional envelopes.

- Machine‑Learning Boundary Detection – Train algorithms on known transitions (e.g., Mesolithic→Neolithic) to predict unseen boundaries given ecological and harshness inputs.

- Cross‑Disciplinary Workshops – Bring together period specialists from each region to debate and, where possible, harmonise terminology and thresholds.

Why This Matters to the Brigantian Project

- Harmonised period envelopes provide temporal bins for comparing migration proxies (artefacts, genomes, isotopes) across our Atlantic‑to‑Baltic transect.

- Identifying over/under‑represented periods helps direct excavation funding toward gap‑filling.

- Transparent revision pathways ensure the model evolves alongside discoveries—avoiding the trap of fossilising outdated local chronologies within our supra‑regional synthesis.

This human‑chronology overlay becomes the scaffold onto which all subsequent archaeological, environmental and genetic layers can be hung—ready to flex as future research sharpens the temporal picture.