The ford sits directly under Kilgram Bridge in North Yorkshire. Grid reference SE191859.

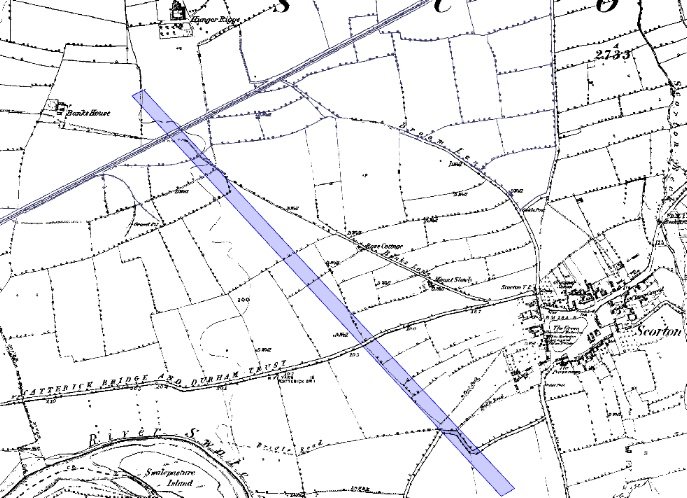

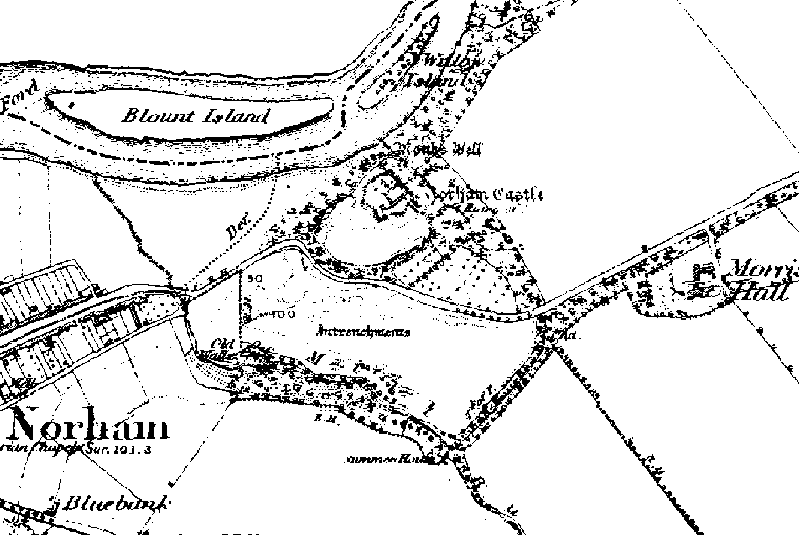

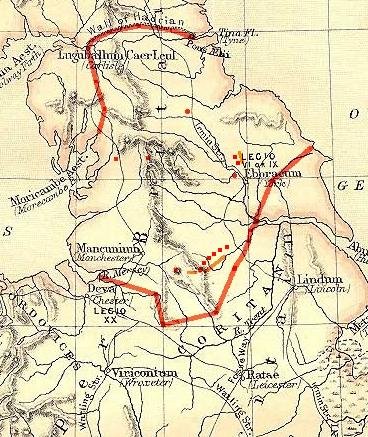

In 1720, the cartographer, Warburton created some of the first extensive maps of Yorkshire and Northumberland. Uniquely, he took pains to record the course of any Roman roads that were still visible, and recorded a Roman road which travelled from Grewelthorpe to Catterick (North Yorkshire). The road is recorded as passing close to Masham, through Kilgram (shown above), where it crossed the River Ure, continuing to Catterick via Newton le Willows and Hornby. This road was confirmed by the antiquarian John Fisher (1) some 100 years later however it has had little recognition in modern times. The course of this road is still visible to the south of Kilgram.

The construction of the ford will be described later, it’s size would tend to indicate this road was an important communication route during Roman times, it’s destination – Catterick being a known major centre will have been an important regional focal point, other sites close to the course of the route include a small camp at Roomer Common and a settlement of probable Iron Age origin close to Horsecourse Hill, Grewelthorpe. Little is known of these sites.

Kilgram Bridge from the air – Multimap.com

Kilgram Bridge in 1856 – OS map from old-maps.co.uk.

Clues that lie below – The Paved Ford

Dating of the ford

Without excavation evidence a firm conclusion as to the period of construction can only be arrived at using evidence as to the visible context of the ford – it’s location under Kilgram Bridge, and it’s manner of construction.

The fact that is sits under a Norman structure, known to exist from at least 1301, and probably built within a few years of the founding of the nearby Jervaulx Abbey – 1145 would tend to suggest it was built in a period prior to the Norman conquest. Other factors such as the building of the bridge directly over the structure indicate it had fallen out of use some time prior to the building of the bridge.

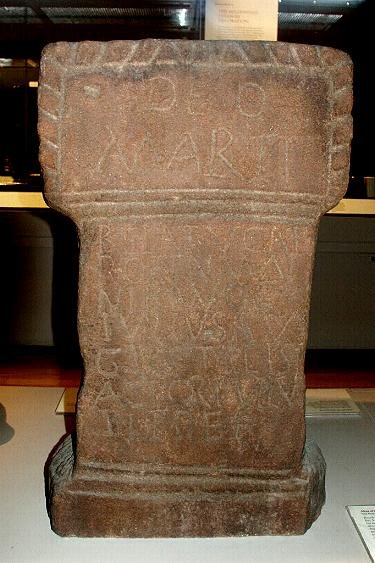

The use of lewis holes in it’s construction, as well as water hard mortar are clear indicators of a Roman origin, these features not re-occurring in Britain until long after the date of the bridge which rests upon it. The extensive use of steel straps to bond the structure together give further evidence of a Roman date. No such structures are known to have been built in either the Norman or Saxon periods.

Further evidence is suggested by the relationship with the Roman road reported by Warburton and confirmed by Fisher.

Taking this evidence together, it seems unlikely that this structure could be anything other than that of Roman origin. Fortunately, it’s watery context means that the wooden parts of its construction are still extant, and perhaps confirmation of it’s date can be obtained in future with the use of dendrochronology.

Construction of the ford

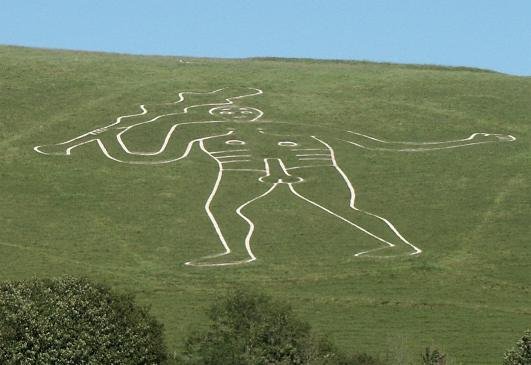

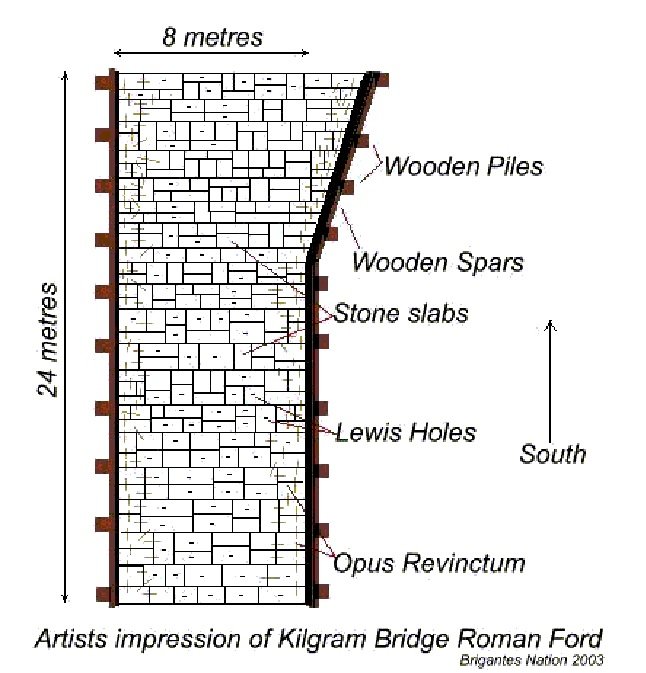

The structure of the ford sits directly under Kilgram Bridge. It is composed of large sandstone slabs, which are well squared, and vary in size from approx 70cm x 150cm to 45cm x 90cm. The slabs are closely laid across the river to form a ford approx 8 m in width and 24m in length, from one bank of the river to the other. Each slab is held together by white mortar.

Built out of sandstone, these very regular and in places massive stone blocks cross the river. The bridge uses it as a foundation.

Along the outside of the paved ford, a regular series of iron straps, held in place by whitened lead can be seen.

In places lengths of timber and the contents of postholes remain intact. Also to be noted is the mortar holding the stones in place.

Along the outside edges of the ford, along its length, a series of iron straps (opus revinctum) serve to further secure it’s structure. These are probably be held in place by now whitened lead, which is typical of Roman construction. Although the majority of the ford is hidden by a covering of marine plantlife, which has the effect of staining the stone red, in places a number of lewis holes – used to lift the stones into place can be seen.

The outer edges of the ford are protected from erosion by the river by a length of wooden plank. The whole structure is held in place by wooden piles approx 20cm in diameter, placed in approx 2m intervals.

One unusual feature of the ford, is that it broadens in width about two thirds of its length towards it’s southern end. It is assumed that this was to accommodate the direction of approach from the south.

Although it is generally considered that the Roman’s used fords extensively as a means of crossing rivers, paved fords are so far extremely rare finds in Britain, in his book “Roman Roads” Richard Bagshawe mentions only three to be known, two of which have been recently lost due to flood damage and development. The ford at Kilgram sits under an already scheduled monument and should be around for some time yet.

Lewis hole.

The only known paved fords in Britain are Roman, the width of this one compares favorably with the Roman ford at Kempston, Beds. And it’s construction appears to have been even more significant. The ford at Kempston apparently lacking the Opus Revinctum.

Known paved fords of Roman origin

There are three known Roman paved fords in Britain (others have been identified but have not been verified). These are at Iden Green (Kent), Poddington (Beds) and Kempston (Beds). The former two are small fords which cross streams. Only Kempston crosses a large river and as such should provide the closest comparison of the construction techniques used.

Discussion

Whilst research is still ongoing, the ford under Kilgram Bridge is highly likely to have been of Roman construction. The building methods and material used, the size of the ford and the known reference to a Roman road passing over this spot all point to this structure being of Roman origin. If this is so, then this ford is one of only four Roman paved fords known in Britain. Furthermore, it is potentially larger and more ornate than the largest Roman ford so far known – Kempston, Beds.

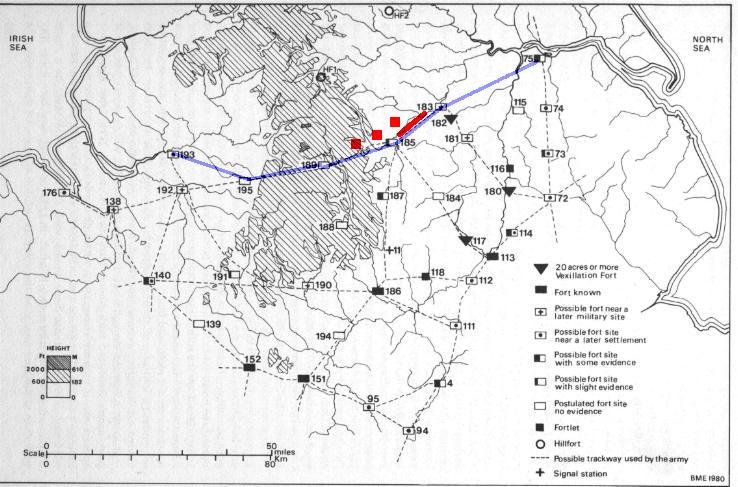

The width of the ford – approx 8m, compares favorably with the average width of major Roman roads in Britain of 22 pedes (6.5m) and importantly, is almost exactly the width of nearby Dere Street (26 pedes, 7.7m) and again marks this route as being of high importance during Roman times.

Of the three Roman mentioned by Bagshawe – Iden Green (Kent), Poddington (Beds) and Kempston (Beds). Only Kempston crosses a large river (The former two are small fords which cross streams.) and would have provided the closest comparison of the construction techniques used, however this was destroyed by recent floods.

The width of the ford – approx 8m, compares favourably with the average width of major Roman roads in Britain of 22 pedes (6.5m) and is almost exactly the width of nearby Dere Street (26 pedes, 7.7m). However, little is known with regard to the relationship between the width of Roman paved fords and the width of the roads they carried..

References

1. History of Mashamshire, John Fisher, 1860.

2. Roman Roads in Britain. Hugh Davies, 2002 Tempus.

3. Roman Roads, Richard W. Bagshawe, 2000, Shire.

4. Kevin Cale Archaeological Consultant – Kilgram Bridge (assessment and evaluation reports) 1998. English Heritage.