Contents

- 1 The first Pope

- 2 Papal duties

- 3 Electing a new Pope

- 4 The second Pope

- 5 Early opposition to Roman Catholicism

- 6 Origins of the term Pope

- 7 The third Pope

- 8 Catholicism in Britain

- 9 Celtic Christianity

- 10 St Aiden

- 11 Syncretism

- 12 St Brigid

- 13 Other examples of syncretism

- 14 Syncretism in Brigantia

- 15 The increase of the Anglo-Saxon influence

- 16 Pope Gregory the Great

- 17 The Gregorian mission of 596AD

- 18 The Gregorian Mission in Brigantia

- 19 York as the ecclesiastical epicentre of the north

- 20 Brigantia as a centre for Christianity

- 21 Monasticism

- 22 The Synod of Whitby

- 23 Lesser known synods held in Britain

- 24 The continued expansion of Christianity

- 25 The coming of the Vikings

- 26 The Viking impact on York

- 27 Beyond the first millennium

- 28 The Normans

- 29 The North Sea Empire

- 30 The Vikings in Normandy

- 31 The East-West Schism

- 32 The Norman Conquest of England

- 33 Edward the Confessor

- 34 Other Claimants to the English throne

- 35 The Battle of Stamford Bridge

- 36 The Battle of Hastings

- 37 The harrying of the north

- 38 The Domesday Book

- 39 Impact on the Church

The first Pope

The title of the first pope in history is traditionally attributed to Saint Peter, who is also revered as one of the principal apostles of Jesus Christ. According to Catholic tradition, Peter was appointed by Christ himself as the first Bishop of Rome, a role that has evolved into what is known today as the papacy. The Catholic Church honours Saint Peter as the first leader of their institution, marking the beginning of a long line of popes that continues to this day. Saint Peter’s Basilica in Vatican City, one of the most significant churches in Christianity, is named in his honour, symbolizing his foundational role in the church. While the term “pope” was not used during his time, Saint Peter’s legacy as the first pope is a cornerstone of Catholic history and tradition.

Papal duties

The Pope, as the Bishop of Rome, holds a position of great significance in the Catholic Church. He is the spiritual leader of approximately 1.3 billion Catholics worldwide and serves as the head of the Holy See, the Church’s central government. The Pope’s responsibilities are multifaceted, encompassing spiritual, doctrinal, and administrative duties. He is tasked with preserving the purity of Catholic doctrine, guiding the Church’s moral and ethical direction, and ensuring the unity of the Church across the globe. The Pope also presides over major liturgical celebrations, including Easter and Christmas, and offers blessings to pilgrims and tourists in Vatican City. Additionally, the Pope meets with bishops from around the world, travels to various countries, and addresses issues of faith and morality, impacting Catholics everywhere. His role as the Vicar of Christ on earth represents Christ to the Church and the world, continuing the apostolic succession that began with Saint Peter.

Electing a new Pope

The election of the Pope, known as a papal conclave, is a process steeped in tradition and governed by specific procedures that have evolved over centuries. When the papacy becomes vacant, the College of Cardinals is convened to elect a new Pope, who is considered the apostolic successor of Saint Peter and the earthly head of the Catholic Church. The conclave is held in the Sistine Chapel at the Vatican, where the cardinals, all under the age of 80, gather to deliberate and vote in secrecy.

The election begins with a special Mass in St. Peter’s Basilica, followed by the cardinals’ seclusion in the Sistine Chapel. Voting takes place through secret ballots, and a two-thirds supermajority is required to elect the new Pope. If no candidate receives the necessary majority after several ballots, a day may be set aside for prayer, discussion, and a re-vote. The ballots are burned after each voting session, with the smoke serving as a signal to the public: black smoke indicates no decision, while white smoke announces the election of a new Pope.

The process is designed to be free from external influence and to ensure that the decision is made through prayerful consideration and discernment. The cardinals are not permitted any contact with the outside world during the conclave, emphasizing the solemnity and confidentiality of their task. The election continues with up to four votes each day until a new Pope is chosen. Upon acceptance of the election, the new Pope chooses his papal name and is introduced to the world with the words “Habemus Papam” or “We have a Pope.”

The current procedures for the papal election were established by Pope John Paul II and later amended by Pope Benedict XVI. These rules are detailed in the apostolic constitution, Universi Dominici gregis, which outlines the spiritual and logistical framework for the conclave. The tradition of the papal conclave underscores the continuity and historical significance of the papacy, reflecting the Catholic Church’s commitment to a process that balances ancient customs with the practical needs of the modern world. The election of a Pope is not only a pivotal moment for the Catholic Church, but also an event of global interest, symbolizing a time of transition and renewal for Catholics around the world.

The second Pope

The second pope in the history of the Catholic Church was Saint Linus, who is believed to have held the papacy from around AD 67 to AD 76-79. He succeeded Saint Peter, who is recognized as the first Bishop of Rome and thus the first pope. The historical records from this period are not comprehensive, but Saint Linus is traditionally considered the second pope based on various historical documents and Church traditions. His papacy followed directly after that of Saint Peter, and he is mentioned by several early Christian writers, including Saint Irenaeus and Saint Jerome, as well as being noted in the Liber Pontificalis, a book containing biographies of popes. Saint Linus’ contributions to the Church include the decree that women should cover their heads during Mass, a practice that reflects the customs of the time. Despite the lack of extensive historical data, the consistent recognition of Linus as the second pope across various sources lends credence to his role in the early Church.

Saint Linus is a figure shrouded in the early mist of Church history. His tenure as pope, from approximately AD 67 to AD 76-79, marks a period where the fledgling Christian community was establishing its identity and governance. While the details of his life are sparse, Saint Linus is recognized for his role in shaping the early Church’s structure and practices. He is traditionally credited with issuing the decree that women should cover their heads during Mass, reflecting the customs of his time. This directive would be one of the earliest known formal liturgical practices of the Church.

The historical Saint Linus is often identified with the Linus mentioned in the Second Epistle to Timothy, suggesting a close association with the Apostles Peter and Paul. This connection underscores the continuity of apostolic succession, a foundational principle for the legitimacy and authority of the papacy. Saint Irenaeus, writing in the second century, affirmed Linus’ position as the second pope, entrusted with the episcopate by the Apostles themselves. This endorsement by early Church fathers lends significant weight to his papal legacy.

Despite the lack of comprehensive records, various sources, including the Liber Pontificalis and writings of early Christian scholars like Saint Jerome, consistently recognize Linus as the immediate successor to Saint Peter. His papacy, though not well-documented, was pivotal in the transition from the apostolic era to the structured hierarchy that would define the Church’s future. The reverence for Saint Linus is evident in his inclusion among the martyrs named in the canon of the Mass, although the historical evidence of his martyrdom is not conclusive.

Saint Linus’ feast day, celebrated on September 23, honours his contributions to the Church. While his papacy was brief, it was marked by the challenges of leading a community during times of persecution and uncertainty. His leadership helped to maintain the unity and faith of the Christian community, setting a precedent for his successors. The veneration of Saint Linus across all Christian denominations that honour saints is a testament to his enduring impact on the Christian faith.

Saint Linus’ papacy represents a bridge between the apostolic leadership of Saint Peter and the developing ecclesiastical structure that would sustain the Church through the centuries. His actions and the traditions surrounding his leadership provide a glimpse into the early Church’s efforts to preserve the teachings and unity of the Christian community in the aftermath of the Apostles’ ministry.

Pope Saint Linus faced a myriad of challenges during his papacy. His tenure was a time of foundational growth and also of great difficulty for the early Christian community. One of the primary challenges he encountered was the task of consolidating the Church’s structure and authority in the aftermath of the Apostles Peter and Paul. With the Christian community still in its infancy, Linus had to contend with the lack of established protocols and the need to develop a cohesive doctrine that would unify believers.

Early opposition to Roman Catholicism

The period of Linus’s papacy was marked by external opposition, particularly from leaders outside of Rome, who may have had differing views on the direction of the Christian faith. This opposition required Linus to be a figure of stability and unity, striving to hold the Church together amidst divergent beliefs and practices. Additionally, the threat of persecution was a constant reality for Linus and the early Christians. Historical accounts suggest that he may have ruled during the time of Emperor Nero, a period notorious for the persecution of Christians, including the Great Fire of Rome in AD 64, which Nero allegedly blamed on the Christians, leading to widespread persecution.

Linus also faced the challenge of establishing liturgical practices, such as the decree that women should cover their heads during Mass, which was a significant step in the formalization of Church rituals. This directive reflected the customs of the time and demonstrated Linus’s role in shaping the early liturgical identity of the Church. The implementation of such practices would have required careful navigation of cultural norms and the expectations of the faithful.

Despite these challenges, Linus’s leadership was instrumental in guiding the Church through its formative years. His actions laid the groundwork for future popes and helped to maintain the continuity of the apostolic tradition, which was crucial for the legitimacy of the papacy. The reverence for Linus is reflected in his inclusion among the martyrs named in the canon of the Mass, although the historical evidence of his martyrdom is not conclusive.

The legacy of Pope Saint Linus is one of resilience and dedication to the Christian faith during a time of uncertainty and transition. His efforts to uphold the teachings of the Apostles and to foster unity within the Church have left an indelible mark on the history of the papacy. While the specifics of his challenges may not be thoroughly documented, the consistent recognition of his leadership across various sources underscores the significance of his role in the early Church.

Origins of the term Pope

The term “Pope” has its roots in ancient languages and carries a rich history. It originates from the Old English “papa,” which was derived from ecclesiastical Latin, and further back from ecclesiastical Greek “papas,” a variant of the Greek “pappas,” meaning “father.” This term was historically used as a title for bishops and patriarchs in various regions, but over time, it became specifically associated with the Bishop of Rome, the head of the Roman Catholic Church. The evolution of the term reflects the Pope’s role as a spiritual father and leader, guiding the Church through centuries of history.

The use of “papa” as a term of respect and endearment for bishops was common in the Christian East by the third century, and was later adopted in the West. The title “Pope” was then increasingly used in the Western Church and was solidified by the time of Leo the Great in the fifth century, who was a significant proponent of the Bishop of Rome’s authority. Since then, the title has been exclusively associated with the leaders of the Roman Catholic Church, signifying their role as the successors of Saint Peter, whom Catholics believe was appointed by Jesus Christ to lead his followers.

The third Pope

The third pope in the history of the Catholic Church was St. Anacletus, also known as Cletus. He succeeded St. Linus and served as the Bishop of Rome from about 76 to 88 AD. His papacy followed that of St. Peter, the first pope, and St. Linus, the second. St. Anacletus is remembered for his contributions to the early church, including the ordination of a number of priests and possibly the establishment of clerical ranks. His feast day is celebrated on April 26, and he is recognized as a saint in the Catholic tradition. The exact details of his life and papacy are sparse, but it is believed that he was martyred for his faith during the reign of Emperor Domitian.

St. Anacletus’ contributions to the church’s development during its formative years were significant. Tradition holds that he established the clerical hierarchy, setting down rules for the consecration of bishops, which was a crucial step in organizing the church’s structure. He is also credited with creating parishes in Rome and assigning bishops to oversee these 25 districts, thereby laying the groundwork for the church’s presence and administrative organization in the city.

Anacletus was born in Athenae, Greece, and his early life was marked by his close association with St. Peter, who ordained him as a priest. This relationship would later lead to his papacy, during which he continued to build on the foundations laid by his predecessors. His papacy, while not extensively documented, is noted for the ordination of several priests, which helped to expand the reach and influence of the church during a time when Christianity was still emerging from its Jewish roots and facing Roman persecution.

The exact dates of his papacy are subject to some historical debate, with estimates ranging from 76 to 88 AD to 79–91 AD, reflecting the challenges historians face when piecing together the early history of the papacy. Despite these uncertainties, it is widely accepted that St. Anacletus played a crucial role in the church’s early growth and the establishment of its traditions and practices.

His death, like many early church figures, is shrouded in mystery, with some accounts suggesting he was martyred under Emperor Domitian, a fate common to many Christian leaders of the time. His burial place is believed to be near that of St. Peter on Vatican Hill, a site that would become central to the Catholic Church.

St. Anacletus’s legacy is also preserved in the liturgy of the Catholic Church, with his name mentioned in the Canon of Mass. This inclusion reflects the enduring impact of his leadership and the respect he garnered within the church. Though the details of his life may be sparse, the structures and traditions he helped to establish have had a lasting influence on the Catholic faith. His feast day, April 26, remains a testament to his sainthood and his role in shaping the early church. The merging of his feast day with that of St. Cletus signifies the recognition of his contributions under both names, further emphasizing his importance in the church’s history.

Catholicism in Britain

Catholicism’s roots in Britain can be traced back to the Roman occupation, but it was during the 6th century that the religion truly began to establish a significant presence.

Christianity’s roots in Yorkshire and the surrounding areas can be traced back to the Roman occupation of Britain. The spread of Christianity during this period was gradual and often intertwined with Roman military and political structures.

By 314 AD, the presence of a bishop from York at the Council of Arles indicates an established Christian community in the region. This early Christian community would have been a mix of Roman settlers, soldiers, and local converts, reflecting the diverse cultural milieu of Roman Britain. The exact nature of Christian worship and organization during this time remains obscure, but it is likely that it followed the Roman model, with a structured clergy and formalized liturgy.

Archaeological evidence, such as the remains of early churches or Christian symbols carved into stones, provides some insight into the presence of Christianity. However, much of the physical evidence from this period has been lost or is yet to be discovered.

The historical record is also sparse, with most of our knowledge coming from later sources such as the writings of Bede, who chronicled the history of the English church several centuries later. Despite these challenges, it is clear that by the end of the 4th century, Christianity had established a foothold in the region, setting the stage for its expansion and the establishment of more formal church structures in the subsequent centuries.

Celtic Christianity

Celtic Christianity refers to the form of early Christianity that was practised among the Celtic peoples of Britain and Ireland. The exact origins of Celtic Christianity are obscure, but it is generally believed to have been introduced to Britain in the 3rd century, possibly earlier. It was distinct from Roman Christianity in several practices, including the calculation of the date of Easter and the style of monastic tonsure. Celtic Christianity’s ascetic nature, community-oriented monasticism, and unique liturgical traditions contributed significantly to its appeal and spread.

The introduction of Celtic Christianity to England is closely associated with the mission of St. Aidan and other monks from Iona, who were instrumental in the conversion of the Anglo-Saxons in the 7th century. The Roman mission, led by St. Augustine of Canterbury, arrived in England earlier, but it was the Celtic missionaries who had a lasting impact on the religious landscape of the region. Their efforts were characterized by establishing monasteries that became centres of learning and spirituality, which played a crucial role in the Christianization of England.

St Aiden

St. Aidan, a figure of pivotal importance in this tradition, was instrumental in spreading this form of Christianity throughout Northumbria. His mission began on the island of Iona, a centre of Irish monasticism, and from there, he was sent to the court of King Oswald in Northumbria. St. Aidan’s approach to evangelism was characterized by its gentle persuasion and respect for the existing culture and traditions of the people. This stood in contrast to the more Romanized form of Christianity that was being promoted in the southern parts of England.

St. Aidan’s mission was marked by the establishment of monastic communities, which became hubs of learning, culture, and spiritual life. These communities were often situated in remote areas, reflecting the Celtic Christian ideal of solitude and communion with nature. The influence of St. Aidan and Celtic Christianity is perhaps best exemplified by the Synod of Whitby in 664, where the differences between the Roman and Celtic practices were debated. Although the Roman practices were eventually adopted, the legacy of St. Aidan’s mission and the distinctiveness of Celtic Christianity continued to influence the religious life of the region

Syncretism

It was not uncommon in the early Christian period for local deities or figures of veneration to be ‘Christianized’ by being associated with saints or incorporated into Christian narratives. This practice allowed Christianity to be more easily accepted by local populations, who could continue to revere their traditional figures under the new religious framework. In the case of Celtic Christianity, this meant that certain characteristics or stories associated with local deities could have been transferred to Christian saints.

For example, some scholars suggest that the attributes of a Celtic deity might be absorbed into the legend of a saint, who then took on aspects of that deity’s identity. This could be seen in the way certain saints are patronized, or the miracles attributed to them, which may reflect the powers or domain of a pre-Christian deity. The process of transforming local deities into saints would have been a gradual and organic one, reflecting the blending of cultures and religious practices that occurred over many centuries.

This form of syncretism was a practical approach to conversion and is a testament to the adaptability and flexibility of early Christian missionaries. They often found it more effective to incorporate elements of the existing belief system into Christianity rather than attempting to eradicate them. This strategy helped to create a sense of continuity and familiarity for the local population, easing the transition to the new religion.

The names of many churches and the saints to whom they are dedicated can provide clues to this syncretic process. In some cases, the name of a church or the saint it venerates may have origins in the pre-Christian past, suggesting a link to a local deity who was revered before the arrival of Christianity. This connection between place, memory, and veneration is a rich field of study for historians and theologians alike, offering insights into the complex ways in which religious traditions evolve and interact with one another.

It’s important to note, however, that while this practice was relatively common, it was not universal, and the extent to which it occurred varied greatly from place to place. The historical record is often incomplete or ambiguous, making it difficult to draw definitive conclusions about the origins of certain saints’ cults or the names of churches. Nevertheless, the evidence that does exist points to a fascinating interplay between Christianity and the local religious traditions it encountered as it spread throughout the Celtic world and beyond.

St Brigid

One notable example of syncretism in Celtic Christianity is the figure of Saint Brigid. Saint Brigid of Kildare, one of Ireland’s patron saints, is a fascinating case where Christian and pagan traditions intertwine. She shares her name with the Celtic goddess Brigid, who was associated with spring, fertility, healing, poetry, and smith craft. The saint’s feast day is on February 1, which coincides with the Gaelic festival of Imbolc, a pagan celebration marking the beginning of spring. This has led many scholars to suggest that the veneration of Saint Brigid may have absorbed aspects of the goddess’s cult.

The legends surrounding Saint Brigid are imbued with themes common to the goddess’s domain, such as the miracle of turning water into beer, which reflects the transformation and life-giving aspects of the goddess. Additionally, the perpetual flame at Saint Brigid’s sanctuary in Kildare, which was maintained by her nuns, echoes the sacred fires that were an important element of ancient Celtic spirituality.

The Church of St. Brigid in Kildare itself is a site of historical significance, believed to have been founded by Saint Brigid in the 5th century. It stands as a testament to the blending of Christian and pre-Christian traditions. The church has been a place of pilgrimage for centuries, attracting those who honour both the Christian saint and the earlier Celtic deity.

This example of Saint Brigid illustrates how the early Christian church in Celtic lands often incorporated elements of local belief systems. By aligning the veneration of Christian saints with pre-existing pagan customs and festivals, the church facilitated a smoother transition to Christianity for the Celtic people. The syncretic nature of such practices allowed for a unique expression of faith that resonated with the cultural identity of the local population.

The legacy of Saint Brigid, both as a Christian saint and a figure with roots in Celtic paganism, continues to be a subject of interest for historians, theologians, and those who follow Celtic spirituality. Her story exemplifies the complex and layered process of religious syncretism that characterized the spread of Christianity in the Celtic world. The enduring popularity of Saint Brigid’s feast day, both within and beyond Ireland, reflects the deep and lasting impact of this syncretic tradition on Celtic Christian heritage. For those seeking to delve deeper into the history and significance of Saint Brigid and other figures like her, a wealth of scholarly literature and historical records are available that explore the rich tapestry of Celtic Christian syncretism.

Other examples of syncretism

One such figure is Saint Columba, also known as Colum Cille, whose life and works are shrouded in both history and legend. Born into a noble family, he became a monk and later founded several monasteries, the most famous being on the island of Iona. His missionary work among the Picts is well-documented, and he is credited with many miracles and prophecies. Some aspects of his veneration suggest a syncretism with earlier deities associated with water and the sea, reflecting his role as a traveller between the islands and the mainland.

Another example is Saint Cuthbert, who lived as a hermit on the Farne Islands before becoming a bishop. His affinity with animals, particularly birds, and his miraculous ability to control the sea and wind, hint at a connection to older nature-based beliefs. The reverence for Saint Cuthbert in the region, especially at the Lindisfarne monastery, which held his relics, suggests a continuity of sacredness from pre-Christian times.

Saint Gobnait is an Irish saint whose worship likely incorporates elements of the deity associated with bees and healing. Her feast day is celebrated in Ballyvourney, where she is believed to have founded a monastery, and where a pattern or pilgrimage takes place annually. The rituals performed, including rounds at the saint’s shrine and the decoration of her statue with ribbons, suggest a syncretic blend of Christian and earlier pagan practices.

In Wales, Saint Winifred’s well is a site of pilgrimage with a long history. The legend of Saint Winifred, involving her beheading and miraculous restoration to life through the intervention of Saint Beuno, may echo earlier myths related to sacred wells and springs, which were often associated with healing and rebirth in Celtic religion.

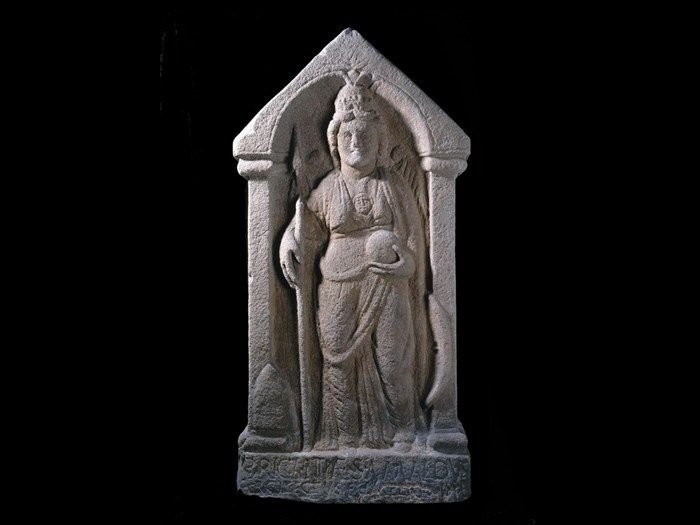

Syncretism in Brigantia

In Brigantia and its surrounding areas, signs of religious syncretism can be observed in various historical and cultural landmarks that reflect the blending of different religious traditions. This syncretism often manifests in the architecture, iconography, and religious practices that have evolved over centuries. For instance, certain medieval churches in Yorkshire exhibit architectural features and decorations that suggest influences from both Christian and pre-Christian, pagan traditions. These elements may include the use of certain symbols or the repurposing of older, pagan sites for Christian worship, which was a common practice as Christianity spread throughout the region. Additionally, local folklore and customs sometimes reveal a syncretic mix of beliefs, where Christian saints and festivals are intertwined with older, Celtic traditions. The celebration of certain feast days, for example, might incorporate elements that are not strictly Christian in origin but have been adopted and adapted into local religious life.

Despite its initial success and widespread influence, often aided by such syncretic practises, Celtic Christianity eventually aligned with Roman practices and in the longer timescale became, in the main, absorbed into the wider Roman church.

The increase of the Anglo-Saxon influence

The early 5th century saw the decline of Roman authority in Britain, creating a vacuum that altered the religious landscape. In this era, Christianity, which had been introduced during the Roman occupation, faced the challenge of maintaining its presence amidst the prevailing pagan practices of the Anglo-Saxon settlers.

The pagan practices of the Anglo-Saxon settlers were rich and varied, reflecting a polytheistic belief system deeply rooted in the natural and supernatural world. Central to their religion were the ése (gods), with Woden, Thunor, and Tiw being among the most venerated. These deities represented different aspects of life and the cosmos, and they were honoured through various rituals and sacrifices. The Anglo-Saxons believed in a host of other supernatural entities as well, such as elves, nicors, and dragons, which inhabited the landscape and influenced daily life.

In the pantheon of Anglo-Saxon deities, Woden and Thunor held particularly significant roles that were reflective of the values and concerns of the society at the time. Woden, known as the chief of the gods, was associated with wisdom, war, and death. His importance is underscored by the fact that one of the days of the week, Wednesday, is named after him—Woden’s day. Warriors sought his favour before battles, hoping for victory and protection, and he was believed to have bestowed the runes upon mankind, a gift of knowledge and communication. As a god who could shape-shift and walk among humans, Woden was a complex figure who embodied the multifaceted nature of leadership and power.

Thunor, the son of Woden and Frige, was the god of thunder, weather, and the forge, representing the elemental force of nature and the craft of blacksmithing. The sound of thunder was attributed to Thunor striking his anvil, a symbol of his strength and connection to the earth. His popularity is evidenced by the discovery of hammer pendants in Anglo-Saxon graves, suggesting a widespread veneration among the people. Thunor’s association with the oak tree and the tradition of the Yule Log may also indicate a role in domestic protection and the cyclical nature of life and seasons.

The roles of these gods were not static; they evolved as the Anglo-Saxons interacted with other cultures and as their own society changed. The later conversion to Christianity, for example, saw a transformation in the way these deities were perceived and worshipped. Woden’s and Thunor’s attributes were sometimes absorbed into Christian saints or practices, illustrating the syncretic adaptation of pagan beliefs into the new religious framework. This blending of traditions ensured that elements of the old beliefs continued to influence Anglo-Saxon culture even after the official adoption of Christianity.

The reverence for Woden and Thunor reflects the Anglo-Saxon understanding of the divine as intimately connected to the natural world, warfare, wisdom, and craftsmanship. These gods personified the forces that shaped their world and their daily lives, from the changing seasons and weather patterns to the outcomes of battles and the pursuit of knowledge. Their stories and symbols remain a testament to the rich spiritual and cultural heritage of the Anglo-Saxons, offering insights into how they made sense of the universe and their place within it.

Cultic practices were an integral part of their religion, often involving the sacrifice of objects and animals to the gods, especially during religious festivals. These acts of devotion were carried out in sacred spaces that could range from timber temples to open-air sites like cultic trees and megaliths. The landscape itself was imbued with spirituality, and many natural features were seen as holy.

The archaeological evidence, along with place-name evidence and texts produced by later Christian Anglo-Saxons, provides insights into these practices. For example, the Franks Casket, a remarkable artifact from the period, depicts scenes from both Christian and pagan narratives, highlighting the syncretic nature of Anglo-Saxon religious life.

Anglo-Saxon funerary practices also offer a window into their beliefs, particularly regarding the afterlife. Burials varied from inhumation to cremation, often accompanied by grave goods that might include weapons, jewellery, and everyday items, suggesting a belief in a life beyond death where such items could be of use.

Over time, as Christianity began to spread across England, these pagan practices were either supplanted by Christian ones or adapted into the new religious framework. Pagan shrines became churches, and some pagan gods were transformed into Christian saints. The process of conversion was complex and gradual, with many pagan elements persisting in local customs and folklore, which can still be observed in some traditions today.

Pope Gregory the Great

Pope Gregory the Great, born around 540 AD as Gregorius Anicius in Rome, was a pivotal figure in the early medieval church, ascending to the papacy in 590 AD after the death of Pope Pelagius II. His early life was marked by a distinguished lineage, being the son of Gordianus, a senator and Prefect of Rome, and Silvia, who hailed from a noble family. Gregory’s education was comprehensive, reflecting his family’s status, and he excelled in his studies, particularly in law, which led to his appointment as the Prefect of Rome at the age of 30, following in his father’s footsteps.

His tenure as prefect was short-lived, however, as Gregory soon turned to a religious life, transforming his family’s palatial home into a monastery dedicated to Saint Andrew, where he became a monk. This period was crucial in shaping his spiritual outlook and administrative skills, which would later define his papacy. As a monk, Gregory was known for his strict adherence to monastic discipline, a trait that would permeate his later reforms.

Gregory’s ascension to the papacy occurred during a time of great turmoil and transition. The Western Roman Empire had fallen, and the church was navigating its role in a changing political landscape. As pope, Gregory was not only a spiritual leader but also took on the administrative duties of governing Rome, showing great care for the welfare of its people, especially during times of famine and plague.

His contributions to the church were manifold. He was a prolific writer, with his texts on theology and pastoral care influencing Christian thought for centuries. His writings included the ‘Dialogues,’ a collection of spiritual teachings and hagiographies, which earned him the title ‘the Dialogist’ in Eastern Christianity. Gregory’s liturgical reforms had a lasting impact on the church, with the Gregorian chant being attributed to him, although this is a matter of some historical debate.

One of Gregory’s most enduring legacies was his commitment to missionary work. In 596 AD, he commissioned the Gregorian Mission, led by Augustine of Canterbury, to convert the Anglo-Saxons in Britain to Christianity. This mission, which reached England in 597 AD, was a cornerstone of Gregory’s vision of a Christian Europe and laid the foundations for the church’s influence in English society.

Throughout his papacy, Gregory also engaged in significant diplomatic efforts, dealing with the Lombards in Italy and correspondences with other rulers, including the Byzantine Emperor. His letters provide a rich source of historical insight into the period and his governance.

Pope Gregory’s health began to decline as he neared the end of his life, but his commitment to the church remained unwavering. He died on March 12, 604 AD, leaving behind a legacy as a reformer, administrator, and a man of deep piety and conviction. His contributions to the church’s liturgy, governance, and expansion through missionary work cemented his status as one of the great leaders of the early medieval church, and he is venerated as a saint in both the Catholic and Orthodox traditions.

The Gregorian mission of 596AD

The Gregorian Mission, also known as the Augustinian Mission, was a pivotal event in the Christianization of Britain. Initiated by Pope Gregory the Great in 596 AD, it aimed to convert the Anglo-Saxons of Britain to Christianity. Augustine of Canterbury, who had been the prior of Gregory’s own monastery in Rome, led the mission. The missionaries arrived in the Kingdom of Kent, a region ruled by King Æthelberht, whose wife, Bertha of Kent, was a Frankish princess and a practising Christian. This connection likely influenced the king’s receptiveness to Christian teachings.

Upon their arrival in 597 AD, the missionaries were granted permission by Æthelberht to preach freely in his capital of Canterbury. The mission’s success was significant, with the king himself converting to Christianity, which set a precedent for his subjects to follow. By the time of the last missionary’s death in 653 AD, Christianity had been established among the southern Anglo-Saxons. The mission’s influence extended beyond Kent, contributing to the Christianization of other parts of Britain and shaping the Hiberno-Scottish missions to continental Europe.

The Gregorian Mission faced challenges, particularly from the long-established Celtic bishops who refused to acknowledge Augustine’s authority. Despite this, the mission laid the groundwork for the establishment of several bishoprics before Æthelberht’s death in 616 AD. However, following his death, a pagan backlash occurred, and the see of London was abandoned.

The Gregorian Mission in Brigantia

Paulinus, a Roman missionary, played a significant role in the early Christianization of Yorkshire. He was consecrated as the first Bishop of York in 625 AD and was instrumental in the conversion of King Edwin of Northumbria to Christianity. Paulinus’ efforts in Yorkshire included the establishment of a bishopric at York and the construction of a church there, where he baptized Edwin and many of his nobles. His mission extended beyond the royal court, as he worked to convert the local populace and establish Christianity as a major religion in the region.

James the Deacon, who accompanied Paulinus on his mission, continued the evangelization of Yorkshire after Paulinus returned to Kent following Edwin’s death in 633 AD. James remained in the North, steadfast in his efforts to spread Christian teachings. He resided near Catterick in North Yorkshire and is known for his missionary work in the area, which included the continuation of services in the church built by Paulinus and the instruction of the local population in the Christian faith.

The dedication of both Paulinus and James the Deacon to their missionary work laid the foundations for the Christian church in Yorkshire, which would continue to grow and shape the religious landscape of the region for centuries to come.

The mission’s legacy in England endured through Æthelberht’s daughter, Æthelburg, who married Edwin, the king of the Northumbrians. Paulinus, accompanied her north and succeeded in converting Edwin and many Northumbrians to Christianity by 627 AD. After Edwin’s death around 633 AD, Æthelburg and Paulinus were forced to flee back to Kent, but the foundations of Christianity they had laid remained.

The Gregorian Mission’s impact on British Christianity was profound. It established a Roman tradition within the practice of Christianity in Britain, which had previously been influenced by Celtic and Romano-Celtic traditions. The mission also played a crucial role in the broader Christianization of Britain, which was largely complete by the seventh century.

York as the ecclesiastical epicentre of the north

York’s ascension to the ecclesiastical epicentre of the north is deeply rooted in its Roman heritage and the significant historical events that unfolded within its walls. The city’s strategic importance began with its establishment as a Roman fortress, Eboracum, around AD 71, which later became a thriving civilian settlement. The Roman influence on York was profound, with the city serving as a bishopric in the 4th century. This early Christian presence laid the groundwork for York’s religious significance.

The pivotal moment in York’s ecclesiastical history came in 306 AD, when Constantine was proclaimed Roman Emperor there. Constantine’s reign marked a turning point for Christianity, culminating in the Edict of Milan in 313 AD, which decreed the toleration of Christianity across the Roman Empire. This act of religious and political significance resonated through the ages, reinforcing York’s status as a centre of Christian worship and governance.

The conversion of King Edwin of Deira after his victory over Wessex, and his subsequent baptism in a wooden church dedicated to St. Peter in 627 AD, signified the royal endorsement of the faith. This wooden church, later rebuilt in stone, was a precursor to the magnificent York Minster that stands today.

Throughout the centuries, York continued to flourish as an ecclesiastical centre. By 735 AD, the city celebrated the appointment of its first Archbishop, Egbert, elevating its religious standing to that of an archbishopric. The construction of churches and the establishment of a monastic precinct in Bishophill during the Anglo-Saxon period further exemplified York’s sacred character.

The intertwining of York’s Roman roots and its Christianization under Constantine provided a historical and spiritual foundation that was recognized and built upon by religious leaders like Pope Gregory I. This blend of ancient prestige and religious significance ensured that York would become, and remain, a beacon of ecclesiastical leadership in the north.

Brigantia as a centre for Christianity

As we have seen, Brigantia, through York, and the work of Paulinus and James the Deacon had started to become a significant Christian power within England. Later events, such as the Synod of Whitby in 664 AD, further solidified its Christian presence by resolving doctrinal disputes and aligning the Church in England with Roman rather than Celtic practices. The Synod of Finghall in 688 adding further weight to the regions’ importance in this period.

Monasticism

Throughout this period, monasticism played a crucial role in the spread of Christianity. Monasteries not only served as centres of worship and learning but also as beacons of Christian culture and civilization in a largely rural and fragmented society. The writings of Bede and Alcuin provide valuable insights into the religious life of the time, indicating a landscape dotted with churches and monastic settlements. These institutions were instrumental in the conversion of the local populace, offering a sense of community and stability in contrast to the upheaval of the post-Roman era.

The legacy of this transformative period is still evident in the numerous ancient churches and religious sites scattered across Yorkshire and its environs. These sites continue to be places of worship and historical interest, reflecting the enduring impact of early Christianity on the cultural and spiritual fabric of the region. The intertwining of faith, politics, and culture during these centuries laid the foundations for the Christian heritage that would shape the history of Britain for millennia to come. The story of Christianity’s survival and growth in this era is a testament to the resilience and adaptability of the faith in the face of changing times and shifting powers.

Augustine’s mission in 597 AD marked the beginning of an unbroken communion with the Holy See, which lasted until the English Reformation initiated by King Henry VIII in the 16th century.

The Synod of Whitby

The Synod of Whitby, held in 664 AD, was a landmark event in the history of the Christian church in England. It marked a decisive moment in the harmonization of ecclesiastical practices between the Roman and Celtic Christian traditions. The synod was convened at the monastery of Streonshalh, known today as Whitby Abbey, under the auspices of the Northumbrian King Oswiu. The primary issue at stake was the method of calculating the date of Easter, which had led to significant discord between the Roman and Celtic churches.

The Roman method of dating Easter followed a system that was aligned with the practices of the wider Christian world, particularly the Church of Alexandria, which had developed a sophisticated calendar based on the cycles of the moon. In contrast, the Celtic church, influenced by the traditions of the monks of Iona, adhered to an older, 84-year cycle for determining the Easter date. This divergence in practice led to situations where different Christian communities in England celebrated the most important Christian festival on different dates, sometimes weeks apart.

The synod was presided over by King Oswiu, who, although a layman, held the authority to make the final decision on the matter. The proceedings included vigorous debate among the leading ecclesiastics of the time, including Bishop Colman, representing the Celtic tradition, and Bishop Wilfrid, advocating for the Roman position. The arguments touched upon various theological and practical considerations, such as the apostolic origins of the practices and the need for a unified Christian witness in the kingdom.

Ultimately, King Oswiu ruled in favour of the Roman method, swayed by the argument that it was the tradition practised by St. Peter, to whom Christ had given the keys to the kingdom of heaven. This decision had far-reaching implications for the English church, leading to the adoption of Roman ecclesiastical customs and the marginalization of Celtic practices. The synod’s outcome also facilitated closer ties between the English church and the broader Latin Christian world, which was increasingly looking to Rome for leadership.

The Synod of Whitby is often cited as a turning point in the history of English Christianity, as it represented the triumph of Roman uniformity over regional diversity. However, it is essential to recognize that the synod was not merely a matter of administrative detail but also a reflection of the broader cultural and political dynamics of the time. The decision to align with Rome can be seen as part of King Oswiu’s strategy to consolidate his authority and integrate his kingdom more fully into the mainstream of European Christendom.

In the years following the synod, the Roman method of dating Easter became standard practice across England, and the influence of the Celtic church waned. The synod’s decision also had a significant impact on the development of monasticism in England, as many monasteries that had followed Celtic practices either adapted to the Roman customs or declined in influence. The legacy of the Synod of Whitby continues to be felt today, as the methods for calculating Easter established at the synod remain the basis for determining the date of the festival in the Western Christian church.

The Synod of Whitby also touched upon broader issues of ecclesiastical authority and practice that had implications for the unity of the church in England. The synod was not just a theological debate but also a reflection of the cultural and political landscape of the time, with the underlying question of whether the English church would align itself with the Roman or Celtic Christian traditions.

The Roman and Celtic churches had developed distinct customs and liturgical practices during their periods of isolation. Another point of contention was the monastic tonsure, the practice of cutting or shaving some or all of the hair on the scalp as a symbol of religious devotion. The Celtic monks wore a distinctive tonsure, shaving the front of the head from ear to ear, which was said to imitate the crown of thorns worn by Christ. The Roman tonsure, however, involved shaving a small round patch on the top of the head, which was believed to represent the tonsure of St. Peter.

The synod also addressed issues of ecclesiastical discipline and the jurisdiction of bishops. The Roman church had a more hierarchical and centralized structure, with clear lines of authority that extended from the local bishop to the pope in Rome. The Celtic tradition, on the other hand, had a more monastic focus, with abbots often holding significant ecclesiastical power, sometimes even over bishops.

The decision of King Oswiu at the Synod of Whitby to follow Roman practices was a turning point for the English church. It led to the adoption of Roman liturgical practices, the reorganization of the church’s hierarchy, and the establishment of closer ties with the continent. This alignment with Rome also facilitated the integration of the English church into the broader currents of European politics and culture.

The Synod of Whitby is remembered as a crucial moment in the history of the English church, setting a precedent for the resolution of doctrinal disputes and the establishment of ecclesiastical uniformity. Its decisions had lasting effects on the religious, cultural, and political development of England, and its legacy continues to be a subject of interest for historians and ecclesiastics alike. The synod’s emphasis on conformity to Roman practices helped to shape the identity of the English church and contributed to the broader narrative of the Christianization of England.

Lesser known synods held in Britain

Beyond the well-documented Synod of Whitby, there were numerous other gatherings, both formal and informal, that addressed various ecclesiastical and secular issues. For instance, the Synod of Finghall in 688AD is mentioned in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, underlying it importance, yet most of our knowledge of what happened has been obscured over time,

Another Synod, in Chelsea in 787 AD, convened by King Offa of Mercia, is notable for addressing matters of church discipline and the relationship between the church and the monarchy.

The Synods of Chelsea, a series of ecclesiastical councils held in Anglo-Saxon England, were significant events that reflected the complex interplay between church and state during the early medieval period. The most notable of these synods took place in 787 AD, presided over by King Offa of Mercia, a powerful ruler known for his influence over the church and his efforts to consolidate his kingdom. This particular synod is often remembered for its association with the controversial elevation of the diocese of Lichfield to an archdiocese, a move that was seen as an attempt by Offa to challenge the primacy of Canterbury and to create an ecclesiastical structure that paralleled his own political ambitions.

The records of the Synod of Chelsea in 787 AD, as preserved in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, indicate that there were contentious discussions, particularly regarding the division of the see of Canterbury. Archbishop Jænberht was compelled to relinquish some part of his bishopric, and Hygeberht was chosen by King Offa to assume the new archiepiscopal status, with Ecgfrith, Offa’s son, being consecrated as king during the same council. This synod was also significant for the vow made by Offa to donate 365 mancuses annually to the papacy, a commitment that historians believe marked the beginning of Peter’s Pence, an annual contribution to Rome by the English Church.

The Synod of Chelsea in 789 AD, another event of note, saw the attendance of both the Archbishop of Canterbury and the newly created Archbishop of Lichfield, along with bishops from various sees such as Dunwich, Leicester, Lindsey, and Winchester. This gathering further illustrates the evolving ecclesiastical landscape of England, where the balance of power between different sees and the relationship with the papacy were subjects of ongoing negotiation and adjustment.

While the Synod of Chelsea in 793 AD is mentioned in historical records, the charter that claims its occurrence (Sawyer 136) is widely regarded as a forgery. This highlights the challenges historians face when attempting to reconstruct the details of these early medieval councils, as the authenticity and accuracy of sources can often be questionable.

The Synods of Chelsea are emblematic of a period in English history where the church was not only a spiritual authority but also a participant in the political machinations of the time. The decisions made at these synods had profound implications for the structure and governance of the church in England, influencing the distribution of ecclesiastical power and the church’s relationship with the monarchy. They also reflect the broader trends of the period, such as the increasing centralization of authority and the desire for a more unified Christian practice across the kingdom.

The legacy of the Synods of Chelsea, particularly the 787 AD council, is multifaceted. On one hand, they represent a moment when the English church took significant steps towards organizational independence and self-governance. On the other hand, they also signify the extent to which secular rulers could exert influence over ecclesiastical matters, shaping the church to suit their political objectives

Another example is the Synod of Clovesho, a series of councils held in the 8th century, which dealt with issues ranging from the observance of Easter to the promulgation of canon law.

The Synod of Twyford in 685 AD, under King Egfrith of Northumbria, is another example where ecclesiastical and secular authorities discussed matters of church property and privileges.

Similarly, the Synod of Llanddewi Brefi in 545 AD, though not in England but in Wales, had a significant impact on the church in Britain, particularly through the figure of Saint David who was said to have performed miracles there.

The Synod of Brefi, for example, is credited with the promotion of the Celtic church’s distinct practices before the Roman traditions became dominant after the Synod of Whitby. The Council of London, on the other hand, represents a moment when the English church took a stand against royal interference, a theme that would recur throughout England’s history, most notably in the later conflicts between church and state during the reigns of Henry II and Henry VIII.

The Council of London in 1107, under Anselm, Archbishop of Canterbury, was pivotal in resolving the investiture controversy in England, setting a precedent for the separation of ecclesiastical and royal powers in church appointments.

These synods were not only about theological debates but also about practical matters such as land rights, tithes, and the church’s role in the legal system. They served as a means for the church to assert its authority, for monarchs to solidify their control over religious institutions, and for the community to seek guidance on moral and social issues. The decisions made in these gatherings had lasting effects on the governance of the church, the development of English law, and the relationship between England and the wider Christian world.

The continued expansion of Christianity

Throughout this period, monasticism played a significant role in the spread of Christianity, with monasteries serving as centres of learning, culture, and religious practice. The influence of these monastic communities extended beyond spiritual matters, as they were also involved in agriculture, education, and the arts, contributing to the social and economic development of the region.

The early years of Christianity in Yorkshire saw the establishment of several significant monasteries, which played a crucial role in the religious and cultural development of the region. The first known monastery was Whitby Abbey, founded in 657 AD, which became a centre of learning and spirituality under the guidance of Abbess Hilda. Following the Synod of Whitby, the monastic movement gained momentum. The Benedictine order, known for its strict adherence to the Rule of St. Benedict, established itself firmly with the foundation of Selby Abbey in 1069.

The coming of the Vikings

The 9th century marked a tumultuous period for the Christian communities in Yorkshire, as they faced the formidable challenge of the Viking invasions. These Norse warriors, hailing primarily from Denmark and Norway, embarked on incursions across the North Sea, bringing with them a wave of destruction and cultural upheaval. The Vikings, known for their seafaring prowess, initially sought to raid and plunder, targeting monasteries and religious sites which were often left unfortified and contained valuable treasures. The impact of these raids was profound, leading to the desecration of sacred spaces and a significant disruption in the ecclesiastical hierarchy and organization within the region.

The Norse settlers in Yorkshire, brought with them their own polytheistic belief system, which was deeply rooted in ritual practice and oral tradition. Their religion was characterized by a pantheon of gods and goddesses, divided into two main groups: the Æsir and the Vanir. The most widely venerated deities were Odin, the god of wisdom and war, and Thor, the god of thunder. These gods were believed to inhabit a cosmos centred around the world tree, Yggdrasil, with various realms existing alongside the human world, Midgard.

Rituals played a central role in Old Norse religion, with public acts of sacrifice, known as blóts, being conducted by kings and chieftains to ensure favour from the gods for prosperity, victory in battle, or good harvests. These blóts often involved offerings of food, drink, and sometimes animals, and were held at significant times of the year, such as the midwinter feast of Yule. Additionally, the Norse practised seiðr, a form of sorcery or shamanism, which was sometimes viewed with suspicion due to its associations with the manipulation of fate.

As the Norse settled and integrated into the local communities, their religious practices began to influence and be influenced by the Christian faith of the Anglo-Saxons. This syncretism is evident in the archaeological record, with artifacts displaying a blend of Christian and pagan motifs. For example, the famous Nunburnholme Cross includes imagery from both belief systems, reflecting the coexistence and merging of religious practices.

The Norse also left a lasting impact on the religious landscape through place names that hint at possible sites of worship. Roseberry Topping in North Yorkshire, known as Othensberg in the 12th century, derives its name from the Old Norse Óðinsberg, meaning “Hill of Odin,” suggesting a place of significance for the worship of Odin.

Over time, the Norse settlers began to convert to Christianity, a process influenced by various factors including political alliances and the practical benefits of adopting the dominant religion of the region. The children of mixed marriages between Norse settlers and native Christians would often be brought up in Christian households, further facilitating the spread of Christianity among the Norse community.

The enduring legacy of the Viking presence in Yorkshire is evident in various facets of cultural heritage, including language, place names, and art. The Old Norse language left its mark on the Yorkshire dialect, and place names with endings such as ‘-by’ and ‘-thorpe’ are indicative of Norse origins. The art of stone carving, particularly the creation of intricately designed crosses and hog-back tombstones, reflects a fusion of Anglo-Saxon and Scandinavian styles. These artifacts often feature a blend of Christian symbolism and pagan motifs, showcasing the syncretism that characterized the post-invasion era.

The Viking impact on York

The Viking influence extended beyond the religious sphere, impacting the social and political landscape of Yorkshire. The establishment of Jorvik, modern-day York, as the Viking capital, signified the Norsemen’s intent to create a lasting presence in the region. The city became a bustling hub of trade and governance, and the Vikings’ administrative and legal systems were integrated with those of the Anglo-Saxons, leading to a unique amalgamation of cultures.

The establishment of Jorvik, known today as York, by the Norse settlers had a profound impact on the city’s Christian structures, both physically and institutionally. Initially, the arrival of the Vikings brought about the desecration and destruction of many ecclesiastical sites, as these were often targeted during raids for their wealth and lack of fortifications. However, as the Norse began to settle and integrate into the local society, a gradual shift occurred, leading to a period of reconstruction and religious syncretism.

The Minster, one of the most significant Christian structures in York, survived the Viking incursions and continued to serve as a religious centre throughout the Viking Age. The 10th century saw the foundation of many of York’s churches, a testament to the resilience and recovery of Christian practices in the area. Archaeological evidence, such as sculptured grave markers from this period, has been discovered at several church sites, indicating a revival of Christian art and architecture influenced by both Anglo-Saxon and Norse styles.

The transition from pagan to Christian burial practices among the Vikings also reflects the influence of Christianity on Norse settlers. The pagan ritual of burying the dead with grave goods was replaced by the Christian tradition of burying them with nothing, signifying a shift in religious beliefs and practices. This change would have had a direct effect on the Christian structures, as churches and their surrounding graveyards adapted to these new customs.

Coins minted in Jorvik during this time provide further evidence of the coexistence of Viking and Christian cultures. Some coins bear the inscription ‘St Peter’s money’, a clear indication of Christian influence, yet they also depict the hammer of the Norse god Thor, showcasing the syncretism that was taking place. This peaceful coexistence likely extended to the Christian structures, which would have been used by both the native Christians and the converted Norse population.

The political landscape of Jorvik under Norse rule also played a role in the development of Christian structures. Wulfstan, the Archbishop of York from 931 until his death around 955, is known to have supported the Viking cause on more than one occasion. His actions suggest a level of cooperation and mutual respect between the Norse rulers and the Christian ecclesiastical authority, which would have influenced the maintenance and establishment of Christian structures within the city.

Beyond the first millennium

By the end of the first millennium, Christianity had firmly established itself in Yorkshire and the surrounding areas. The landscape was dotted with churches, monasteries, and other religious institutions, which not only served as places of worship but also as centres for community life and learning. This period laid the foundations for the rich Christian heritage that would continue to shape the history and culture of Yorkshire for centuries to come.

The transformation of Yorkshire from a region influenced by various pagan traditions to one dominated by Christianity was not a swift or uniform process. It involved the interplay of local customs, the persistence of missionaries, and the strategic support of influential leaders. The legacy of this transformative era is still evident in the region’s historic churches, religious art, and the enduring stories of saints and scholars who contributed to the Christianization of Yorkshire.

The Normans

The Normans, known for their profound impact on European history, originated from Norse Viking settlers. These adventurers from Scandinavia began to arrive in what is now Normandy, France, during the 9th and 10th centuries. Their integration into the Frankish lands was solidified through the Treaty of Saint-Clair-Sur-Epte in 911, when Rollo, a Viking leader, pledged fealty to King Charles III of West Francia.

This agreement granted them land and marked the beginning of the Duchy of Normandy. Over time, the Norse settlers intermingled with the local Frankish population, adopting their language and customs. By the end of the 10th century, these Norsemen had transformed into the Normans, a distinct cultural group that spoke a dialect of Old French known as Norman French.

The Normans retained their martial prowess, a legacy of their Viking ancestors, and became renowned as formidable warriors and horsemen.

The perception that many senior Normans appeared to come from nowhere can be partly attributed to their Viking roots. The Vikings, known for their seafaring prowess and expansive raids, often established settlements far from their original homelands. When they settled in what became Normandy, they brought with them a culture of mobility and a tradition of earning status through valour and conquest rather than through hereditary titles alone. This cultural heritage meant that individuals could rise to prominence based on their achievements and loyalty to their leaders, rather than solely by birthright.

Moreover, the social structure of the Viking society was relatively fluid compared to the rigid feudal systems developing elsewhere in Europe. This fluidity allowed for the emergence of new leaders and warriors who might not have had the opportunity to ascend in more stratified societies. As the Normans assimilated into Frankish culture, they retained some of these aspects, which contributed to the dynamism of their aristocracy.

Additionally, the process of assimilation and the establishment of the Duchy of Normandy under Rollo involved the granting of lands and titles to Viking warriors by the Frankish king. This act created a new class of nobility that did not exist before, effectively allowing these ‘new men’ to emerge in the historical record seemingly from nowhere.

The Normans’ reputation for military skill and their strategic marriages also played a role in their rise to power. They often secured alliances and lands through these unions, which could elevate individuals and families to positions of significant influence rapidly.

Furthermore, the Normans were adept at adopting and adapting the administrative systems of the lands they conquered, which often obscured the origins of their leading figures. As they expanded their territories, the Normans integrated local elites and appropriated their titles, further complicating the tracing of lineages.

The Viking heritage of the Normans, characterized by a culture that valued individual merit and military accomplishment, combined with the opportunities presented by their new settlements in Normandy, allowed many to rise swiftly to prominence. This phenomenon, coupled with strategic marriages and the adoption of local titles, contributed to the impression that senior Normans emerged from obscurity.

The conversion of the Normans to Christianity was a gradual process that began before their emergence as a distinct group in the 9th and 10th centuries. Initially, the Normans were primarily pagan. Their conversion began in earnest when Rollo, a Viking leader, agreed to be baptized and adopt Christianity in exchange for legal recognition of his lands from the Frankish king Charles the Simple around 911 CE. This political and religious shift was part of a broader trend of Christianization among the Viking populations in Europe during this period. Over time, the Normans fully embraced Christianity, which played a significant role in their culture and expansion

.The regional and political differences between the Vikings who settled in England and those in Normandy were significant and had lasting impacts on the events of the Norman Conquest and the subsequent history of England. The Vikings in England, known as the Danelaw, retained strong cultural ties to Scandinavia, which influenced the political landscape of England, especially during the reign of the Danish King Cnut who established a North Sea Empire.

The North Sea Empire

The North Sea Empire, also known as the Anglo-Scandinavian Empire, was a remarkable political entity that emerged during the late Viking Age, encompassing the kingdoms of England, Denmark, and Norway between 1013 and 1042. This empire was a personal union under the rule of King Cnut the Great, who managed to unite these territories through conquest and inheritance, creating a domain that stretched across the North Sea.

The empire was characterized by its thalassocracy—a form of government where the sea was the primary means of unification and power. The maritime prowess of the Vikings played a crucial role in maintaining the Coherence of this empire, which lacked the traditional land-based infrastructure of contemporary states.

The inception of the North Sea Empire can be traced back to Sweyn Forkbeard, Cnut’s father, who first conquered England in 1013. Upon his death, the realm was divided, but Cnut, demonstrating both military skill and political acumen, managed to reclaim and consolidate his authority over England in 1016, Denmark in 1018, and eventually Norway in 1028. His reign marked the zenith of the empire’s power, making him one of the most formidable rulers in Western Europe at the time.

Cnut’s strategy to maintain control over his diverse territories included fostering cultural ties and implementing systems of wealth and custom that bridged the Danish and English societies. His efforts to integrate the different regions under his rule were not just about expanding his dominion, but also about creating a stable and unified empire. The North Sea Empire’s influence extended beyond its borders, affecting trade routes, diplomatic relations, and even ecclesiastical affairs, as Cnut managed to secure concessions from the Catholic Church, enhancing the prestige of his rule.

The empire’s existence was relatively short-lived, however, as it began to fragment following Cnut’s death in 1035. His sons, Harold Harefoot and Harthacnut, succeeded him in parts of his empire, but were unable to maintain the unity and strength that their father had established. By 1042, with the death of Harthacnut, the personal union of these kingdoms dissolved, and the North Sea Empire ceased to exist.

The Vikings in Normandy

In contrast, the Vikings in Normandy assimilated to a greater extent with the local population, adopting Christianity and eventually forming the Duchy of Normandy. This difference in assimilation levels played a crucial role during the Norman Conquest, as the Normans, descended from these Vikings, had developed a unique identity that combined Norse and Frankish elements.

The military strategies and defences also differed, with the Vikings in England facing massacres due to their responses to raiding and settlement, while in Normandy, such circumstances allowed for growth and power. The conquest of England by the Normans, led by William the Conqueror, was not just a military campaign but also a significant cultural and political shift. The Normans introduced feudalism, reshaped the English language, and transformed the social and political structures of England.

The Viking settlements’ differences in England and Normandy laid the groundwork for these changes, as the Normans brought with them a distinct culture that was a fusion of their Viking heritage and the French influence they had absorbed in Normandy. The impact of these differences continued to shape England’s development for centuries, influencing its language, laws, and societal norms. The Norman Conquest marked a pivotal moment in English history, where the legacy of the Vikings, through their Norman descendants, left an indelible mark on the country’s trajectory.

The East-West Schism

The East–West Schism, also known as the Great Schism of 1054, was a pivotal event in Christian history that led to the permanent division between the Western Church, which evolved into the Roman Catholic Church, and the Eastern Church, which became the Eastern Orthodox Church.

The schism was the culmination of centuries of gradual separation characterized by theological, political, and cultural differences.

The main theological differences that contributed to the East–West Schism centred around complex doctrinal disputes. One of the most significant issues was the Filioque controversy, which involved the wording of the Nicene Creed, specifically whether the Holy Spirit proceeds from the Father alone, as the Eastern Church asserted, or from the Father and the Son, as added by the Western Church. This addition by the Western Church was not accepted by the Eastern Church, leading to a fundamental disagreement on the nature of the Trinity.

Another theological dispute was the use of unleavened bread (azymes) in the Eucharist by the Western Church, which was opposed by the Eastern Church that used leavened bread. The East held a more mystical approach to theology, deeply rooted in Greek philosophy, which often led to a speculative understanding of doctrine. In contrast, the West’s theology was influenced by Roman law, leading to a more practical and juridical approach.

These differences in theological perspective and practice reflected the diverse cultural and intellectual landscapes of the Eastern and Western parts of the former Roman Empire, and contributed to the growing estrangement between the two branches of Christianity. The East emphasized the importance of maintaining the purity of ancient Christian traditions, while the West was more open to doctrinal development and change, which was another point of contention.

The question of papal supremacy was also a major theological sticking point, with the Eastern Church rejecting the Pope’s claim to universal jurisdiction over all Christians.

The political landscape also influenced the schism, with the coronation of Charlemagne as Emperor of the Romans by Pope Leo III in 800, challenging the Byzantine Empire’s authority and leading to disputes over territorial and ecclesiastical jurisdiction. The formal split began in 1053 when the Latin churches in Southern Italy were ordered to adopt Western rites, leading to the closure of Greek churches in the region. In retaliation, Patriarch Michael I Cerularius of Constantinople closed all Latin churches in Constantinople.

The situation escalated in 1054 when Cardinal Humbert of Silva Candida excommunicated Cerularius, who in turn excommunicated Humbert and the other papal legates. Despite the mutual excommunications, relations between the Eastern and Western Churches continued, albeit strained.

The schism was not fully realized until later centuries, as the two churches grew apart in doctrine and practice. Efforts to reconcile the churches have occurred throughout history, with the mutual excommunications lifted in 1965 by Pope Paul VI and Patriarch Athenagoras I. However, the East–West Schism remains a significant historical and religious divide, marking the separation of the two largest denominations in Christianity.

The Norman Conquest of England

As the dawn of the 11th century cast its light over Europe, the stage was set for an event that would irrevocably alter the course of English history—the Norman invasion. From a religious perspective, this epoch was not merely a clash of armies, but also a profound spiritual contest. The Normans, themselves devout Christians, were led by Duke William of Normandy, who sought the blessing of Pope Alexander II for his quest to claim the English throne—a throne promised to him by the childless Edward the Confessor, as some accounts suggest. This papal endorsement bestowed a veneer of divine right upon William’s campaign, framing it as a righteous conquest rather than mere territorial expansion.

Edward the Confessor

Edward the Confessor, born around 1003 to 1005, was the penultimate Anglo-Saxon king of England and is often regarded as the last king of the House of Wessex. His reign, which lasted from 1042 until his death in 1066, was marked by relative peace and prosperity, despite the political machinations that characterized the latter part of his rule. Edward was the son of Æthelred the Unready and Emma of Normandy, which connected him to both the old line of Anglo-Saxon rulers and the influential duchy of Normandy. His early years were spent in exile in Normandy following the Danish conquest of England, but he returned to the throne upon the death of his half-brother Harthacnut.

Edward’s reign was largely peaceful, with occasional skirmishes with the Scots and Welsh, and he is credited with maintaining an efficient financial and judicial system, as well as fostering trade. However, his introduction of Norman friends to court stirred resentment among the English nobility, particularly the powerful houses of Mercia and Wessex. For the first decade of his rule, the real power behind the throne was Godwine, Earl of Wessex, whose daughter Edith Edward married in 1045. This alliance, however, did not prevent a breach between the two men, leading to Godwine’s temporary exile.

The return of Godwine and his family to power in 1052 marked a decline in Edward’s influence, and the king’s later years saw the Godwin family, especially Godwine’s son Harold, take on a more prominent role in the governance of the country. Edward’s death in 1066 led to a succession crisis that ultimately resulted in the Norman Conquest of England.

The death of Edward the Confessor in January 1066 left a power vacuum that set the stage for one of the most pivotal moments in English history. Edward’s demise without a direct heir led to a contentious succession crisis. Harold Godwinson, a powerful noble and Edward’s brother-in-law, swiftly claimed the throne. However, the legitimacy of his claim was clouded by the alleged promise

Edward had made to his distant cousin, William, Duke of Normandy. Historical accounts suggest that during a visit to England in 1051, William may have secured a promise from Edward for the English crown. This claim is further complicated by an event in 1064, when Harold Godwinson himself was shipwrecked on Norman shores and supposedly pledged his support for William’s claim to the throne, possibly under duress.