Contents

Chapter 3: The British Henge Complexes

In a few locations across Britain, henge complexes have been recognised. These are groups of henges and other monuments that were apparently built together to create ritual landscapes – widespread areas that were probably intended to be seen as a landscape group. The more famous of these include Avebury with its avenues of stones leading to ancient burial chambers, and the extraordinary giant mound of Silbury Hill.

Image: Silbury Hill, Wiltshire. George Chaplin.

It is worthwhile taking a detailed look at the larger henge complexes in Britain to understand how these complexes came into being, and what similarities and differences exist between these and the Sacred Vale.

Stonehenge

The most famous henge complex in Britain is located at Stonehenge. Here, the relatively small henge of Stonehenge itself is associated with a group of monuments forming a complex that spreads over a significant portion of Salisbury Plain. This covers an area a little over four miles east to west and two and a half miles north-south.

The Stonehenge complex incorporates the largest henge known in Britain – Durrington Walls. This is an irregular circular henge over 500m in diameter. Stonehenge, by comparison, although more visually impressive due to its huge standing stones, appears as a lesser monument of 100m or so in diameter.

What we can see at Stonehenge is a collection of different monuments that sprung up over at least a thousand years. The first monuments were probably the long barrows. Not long afterwards, the cursus monuments were created and in 3,200BC the first ditch was cut for the henge at Stonehenge. Coneybury henge was

completed around 2,800BC, Durrington Walls henge came along around 2,700BC and Woodhenge was a relatively late development at around 2,200BC.

As has been mentioned, henges and other ritual monuments underwent ongoing refurbishment. Stonehenge itself had many phases of building which culminated in the raising of the stones, a task that was done in several stages lasting more than 100 years.

The dates mentioned are based on the results of carbon dating of a few dozen finds from the features mentioned. It is likely that in the future more dates will be forthcoming that will allow this chronology to be refined, but nonetheless these represent the most comprehensive set of dates from any monument complex in Britain.

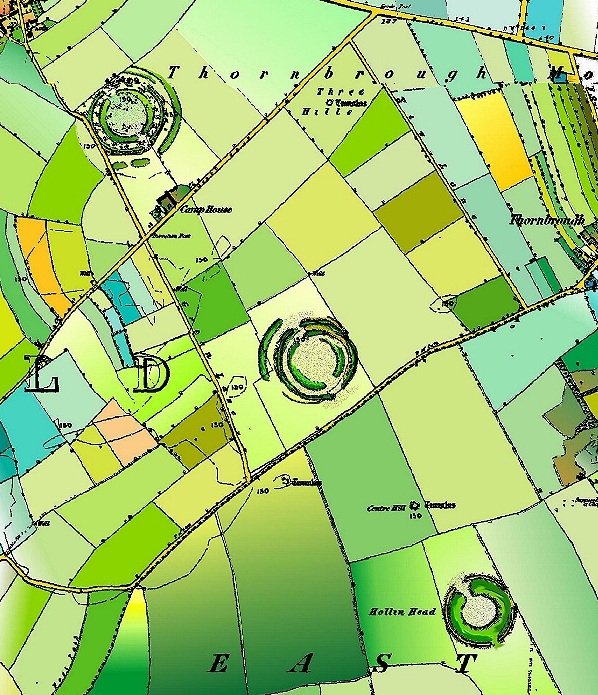

Image: The Stonehenge monument complex, Wiltshire.

The above diagram shows the layout of the Stonehenge complex. Note the relationship with the River Avon. Henges and other Neolithic ritual monuments have been noted as often having a close relationship with bodies of water and in the case of Stonehenge, the River Avon has been suggested as providing a link between Durrington Walls and Stonehenge via The Avenue.

It is clear that this is a monument complex that has evolved. The individual components show a construction that was evolving as was the complex itself as each new component was added.

Thus, whilst there is little doubt that each new component recognised and respected

the existing monuments that were already there, each was a one-off construction. In other words, there is little to suggest that Stonehenge was the culmination of an original master plan. Each new generation came to the complex with fresh ideas that were turned into new structures within an existing sacred space.

This explanation fits well with the dating evidence so far provided. It also fits with various designs seen in the complex, and it paints an interesting picture of one of Neolithic Britain’s most important ritual landscapes.

Image: Stonehenge, Wiltshire. C. 1930.

From the dating evidence available, Stonehenge appears to have started out as a locally important burial site whose significance took on a communal bias with the building of the two cursus monuments.

At this time, Stonehenge was not untypical of a great many sites throughout the British Isles. Its Greater Cursus was slightly above average size and was one of some seventy or more such constructions that were created throughout most of Britain.

When it came time for the building of the first henge, this was c.90m in diameter – certainly larger than many but not anywhere near the largest. Coneybury Henge followed, but was even smaller.

It is likely that by this time Stonehenge was still a monument complex of mainly regional importance. This is assuming that the size of the monument has a relationship with the number of people attending the site. The structures created at Stonehenge did not attain truly monumental size until later in the Neolithic calendar with the building of Durrington Walls in 2700BC.

Image: Stonehenge, Wiltshire. C. 1930.

If the size of the monument does have a relationship to the importance of the site and the numbers of people attracted to the area, then Durrington Walls turned the Stonehenge complex into one of national significance. If, as has been suggested, both Durrington Walls and Stonehenge were used simultaneously then the ritual space created covered almost a mile in length and could have accommodated an enormous number of people.

Seen in this context, Stonehenge could be interpreted as a relatively late developer, a site whose importance and fame gradually increased over the time until it blossomed at the very end of the Neolithic period.

It is worth noting that the issue of dating is likely to come up over and over again. It may be, and possibly should be that Durrington Walls is much older than current dates suggest. However, the main point to note is that Stonehenge appears to be a ritual site that evolved. Each monument within the complex is unique, and it is likely that each had a different designer.

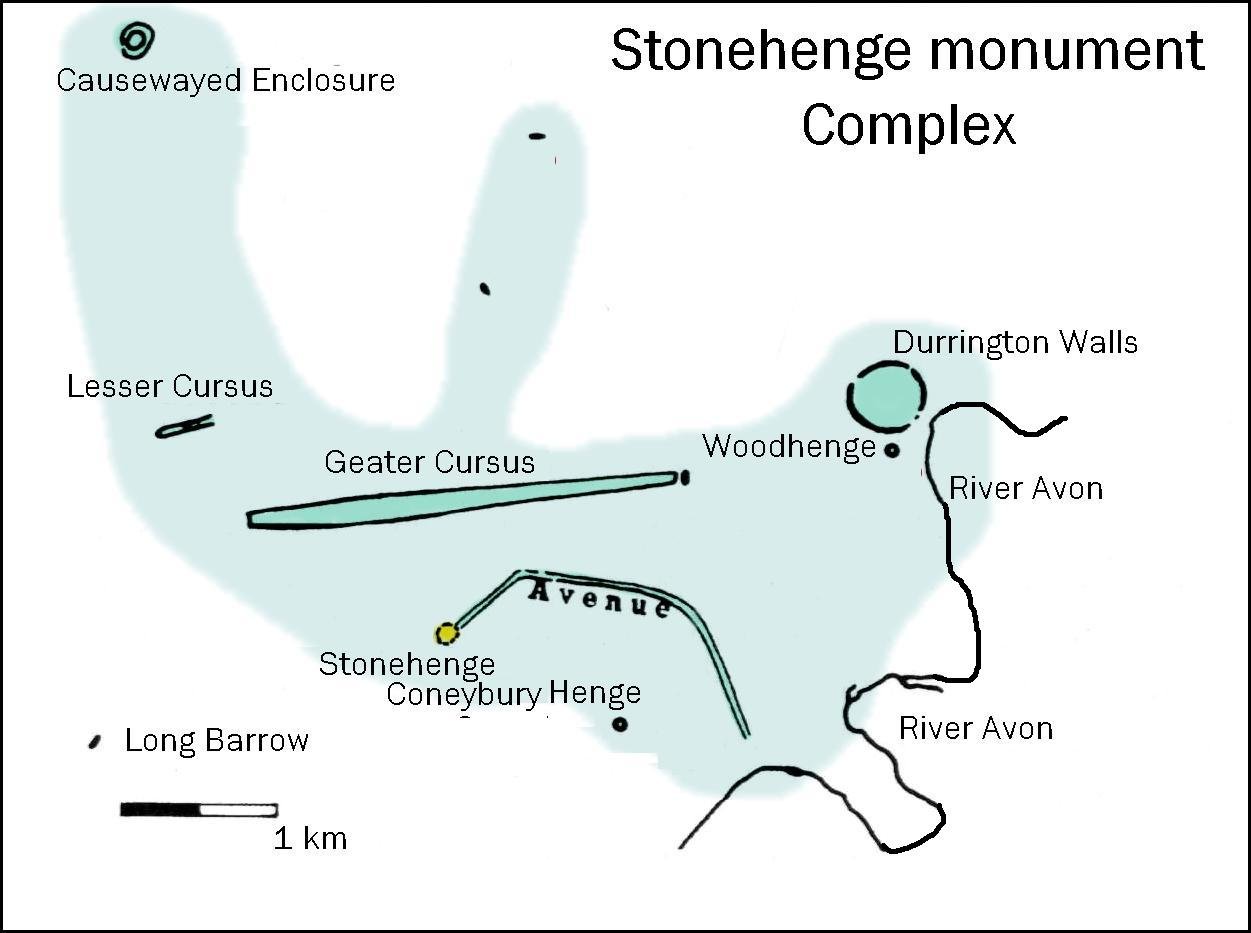

Avebury Monument Complex

The Avebury complex, which focuses on the huge Henge at Avebury (350m in diameter) also lays claim to a monument complex of extremely impressive proportions.

Image: Avebury monument complex. After Harding.

Linked to the henge at Avebury are various monuments covering a very broad timescale. Included is the enormous artificial mound that is Silbury Hill. Silbury Hill was for over a thousand years the tallest man-made structure in the world and was at least 30m in height.

The earliest monument in the complex is the large causewayed enclosure of Windmill Hill. This was a space of 21 acres enclosed by earthwork banks and ditches built as three concentric rings. Although it is thought that causewayed camps did not have an overt ritual function, they are seen as the forerunner to the later henges and other monuments.

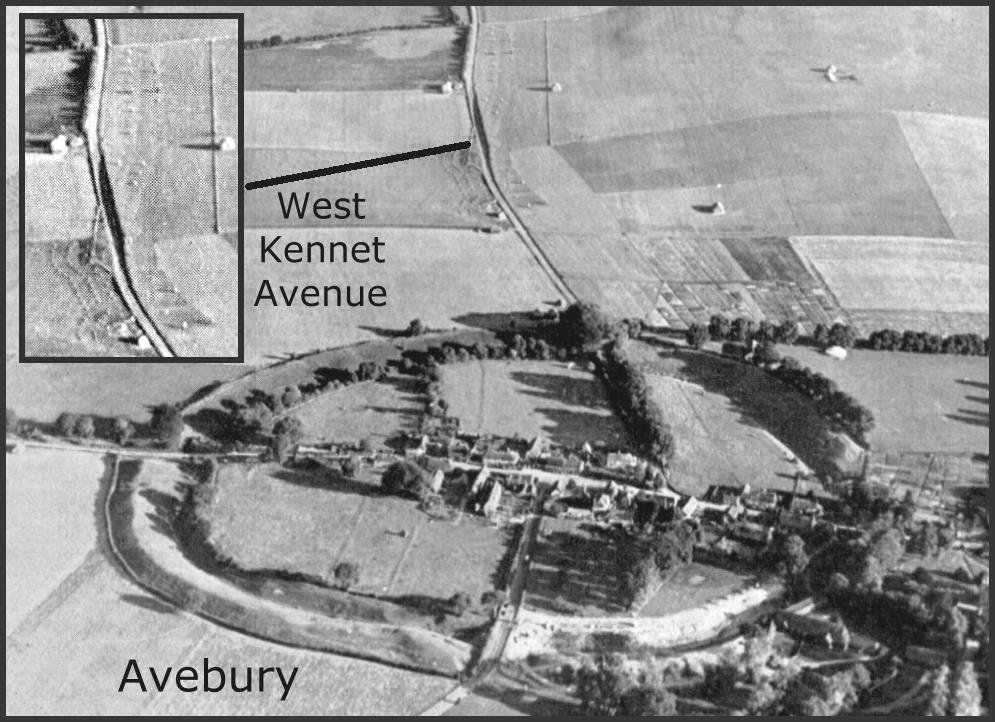

The henge at Avebury has four opposed entrances and was built with a bank that was 30m wide and 6.7m high. The outer stone circle at Avebury sits within the ditch of the henge and creates the largest stone circle in Britain – 330m in diameter. The henges were created around 3,500BC and the stones, including the avenues and The Sanctuary were probably added around 2,000 BC.

The two avenues at Avebury are themselves monumental constructions. The Beckhampton Avenue, although now mostly lost, was at least one and a half miles long. Fortunately, the West Kennet Avenue is largely complete (although this is the result of recent reconstruction) and leads away from Avebury to The Sanctuary,

about one and a half miles to the south, it contains around one hundred standing stones.

At the end of West Kennet Avenue, The Sanctuary was originally a monument of six concentric rings of timber posts some 20m in diameter. In its final stage of construction, a 40m stone circle was erected around the posts and a smaller, inner circle of stones replaced one of the post rings. The Sanctuary never had earthwork banks or ditches.

Avebury is perhaps Britain’s most impressive henge and stone circle, the entire structure was excavated and re-erected during the early 20th century, something that would be regarded as unthinkable today.

Image: Avebury Henge, Wiltshire, S. Piggot.

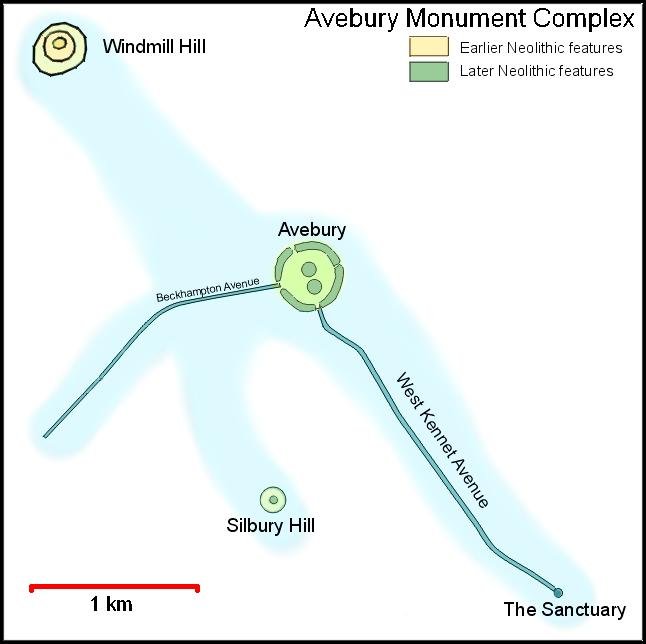

The Knowlton Henge Complex

Image: Knowlton Monument Complex, Dorset.

The Knowlton ritual monument complex consists mainly of henge or henge-like structures and is notable for its compact design.

Three henges laid out almost in a straight line are the North, Centre and South Circles. There is a noticeable clustering of barrows to the north and south of the main monuments.

A church sits within the Centre Circle and that shows that the religious significance of the area has not been completely forgotten.

The North Circle encloses a slightly oval area measuring 70 x 80m, it has a single entrance. The central circle has an irregular ditch that encloses an area of c. 100m in diameter. This henge has three entrances, but it is not clear if the north and south entrances were part of the original structure.

The southern circle is the largest, measuring approximately 250m in diameter. There is no evidence of an entrance, though this may have been removed during construction of the road and the other modern structures.

Little dating evidence is available for the henges at Knowlton and one structure, the “Old Churchyard”, has been suggested as having a post prehistoric date.

Also notable at Knowlton is the Great Barrow. This is 7m in height and is 40m in diameter. From air photography, this barrow has been noted as having two ditches. A feature that has been noted in early barrows where the single ditch of a Neolithic barrow has had a further ditch added when the barrow was enlarged during the Bronze Age.

The Ring of Brodgar complex

Image: Ring of Brodgar ritual complex-Orkney. Image: Ring of Brodgar ritual complex-Orkney. |

The most extensive of the better known complexes is that located in Orkney, and comprises the dramatic stone circles of the Ring of Brodgar and the Stones of Stenness.

Stones were used in ritual monuments from a very early date in the Orkney Islands, probably due to the rapid exhaustion of suitable local timber supplies.

Two major henge-like monuments were erected using huge stone slabs quarried from close by. The resulting monument complex is one of the most spectacular ancient sites in the world.

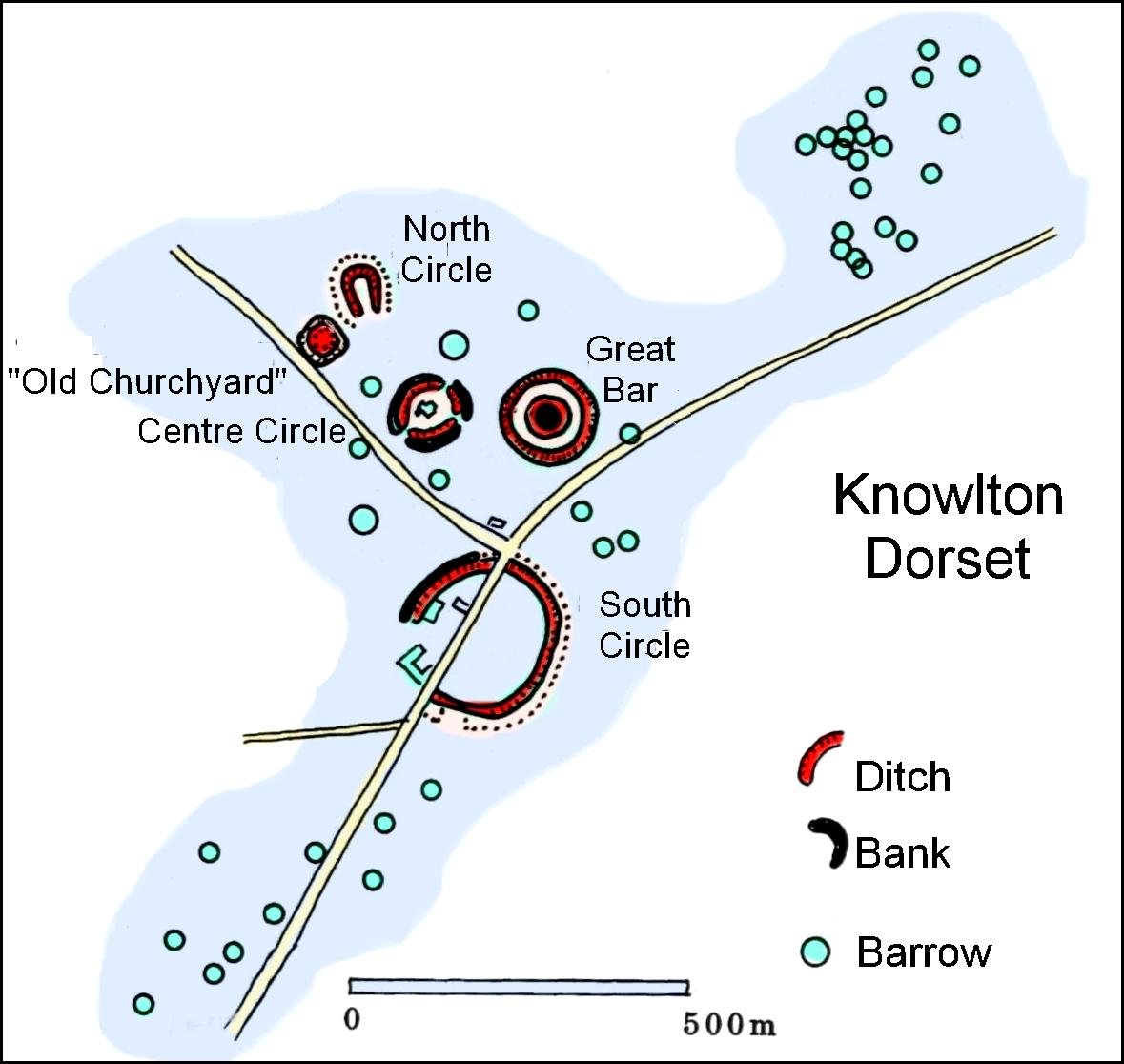

Millfield Henge Complex

Image: Millfield monument complex, Northumbria.

The monument complex at Millfield in Northumberland is a set of six henges that each share a very similar construction spread over quite a large area – almost four miles north to south and three east to west.

The complex consists of Millfield North, Millfield South, Coupland, Ewart, Akeld and Yeavering. Two of the henges here have been dated to a surprisingly late time. Millfield North provided a date of c. 2,250BC and Coupland has provided a date of c. 2,200 BC.

Again, a relationship with water can be seen, and five of the six henges form a roughly straight alignment north-south.

Image: Avebury, Wiltshire. Insert – West Kennet Avenue. Major G. W. G. Allen.

The most famous of the henge complexes are Stonehenge, Avebury and the Ring of Brodgar in the Orkneys.

These complexes hold some of the largest structures of the Neolithic world and have been interpreted as creating extremely significant ritual landscapes, they drew people far beyond what are thought of as local boundaries.

Dating of the period of use for henges has remained problematic due to the lack of dateable finds, including organic material from the bottom of the few henges so far excavated. This means that for complexes in particular there still remains a question: were the monuments within the complex built and/or used simultaneously, or were they a protracted series of developments indicative of an evolving pattern of use?

Comparing the different complexes reveals a number of themes.

It is probable that whilst some complexes were built over a very long period of time, others were part of a single plan and much of the complex that we see today was the outcome of that plan.

At Stonehenge, we see that the variety of monument types, backed up by dating evidence, shows a complex that was the outcome of a gradual incremental design. Millfield, on the other hand, is more likely to have been built to a single concept – a deliberate goal of creating a widespread monument complex.

It should be emphasised that except for the Stonehenge dates, very few samples are available for the other monuments, and this date analysis must therefore not be thought of as absolute evidence.

A number of the complexes form linear alignments; although some (such as Knowlton) may be entirely accidental, at Millfield and at Brodgar there is more clear evidence of such linear relationships.

Most of the henge complexes also show a relationship with water. Five of the six henges at Millfield link up to form a path through a valley where two rivers meet. At Brodgar the two main ritual sites appear to create a link through water between two bodies of land.

At Stonehenge the River Avon forms a ritual routeway between the two major sites. Two other sites, Conybury and Woodhenge, also appear to relate to the river. It should be noted that during the Neolithic period a great many lakes left after the Ice Age would have existed. This may be an important aspect of the Neolithic landscape that we miss today.

The monuments of the Sacred Vale appear to have been built along two straight lines that converge at the Devil’s Arrows standing stones at Boroughbridge. This gives the impression that at some point a plan for this ritual landscape was laid out. Almost from the start, it was decided that it should stretch through a massive part of the landscape. The identical nature of the monuments, as seen at Millfield, would tend to agree with this suggestion.

This created a truly monumental complex that is twenty miles in length and apparently built to a single master plan, whilst still referencing earlier monuments within the area.

In the next chapter we shall look at the monuments of the Sacred Vale in more detail and expand on a number of these themes to see how and why they may apply.