Chapter 4: The early development of The Sacred Vale

The story of the Sacred Vale begins to the best of our knowledge at Thornborough and starts in the early Neolithic period, from 4,000 BC to 3,000 BC. During this period, many of the low-lying areas of England, including the areas between the rivers Ure and Swale, were heavily wooded, not cleared as they are today.

This river-dominated context provides something of a clue as to the reasons why people started to come to Thornborough. The landscape here had a major natural feature, this was the River Ure. Rivers were important to people because they were natural route-ways – carving their way through the landscape.

Travel along a river, even along its banks, particularly in summer when water levels are low may well have been the easiest form of travel compared to cutting through the many dense forests that covered the British countryside at the time.

Rivers were also a natural source of food and water, again during the summer months, the low water helped to concentrate fish, making them more abundant and easier to catch.

The River Ure, seen as a route-way, is of great potential importance. It cuts through half the width of Britain, leading from the heart of the Yorkshire Dales to the Humber Estuary, a place of great potential importance in terms of trade.

Rivers were also important to our Neolithic ancestors for another reason – a religious importance. Rivers like the Ure and Swale are powerful symbols of the natural world, they speak of a whole series of processes on which the lives of people to this day depend. They speak of life in the sense that not only do they provide water, but they also provide a range of other natural resources. Rivers also have a darker side. They have the power to take life, they can flood, they can be unpredictable and can destroy. The River Ure, as it flows through the landscape, is a powerful symbol of the natural world.

Image: Bronze Age square house. Artists impression. Joanne.

This simple observation begins to tell us why Neolithic communities started to come to this plateau between the Swale and Ure Rivers during the fourth millennium BC. It may also explain the first monument that they built here.

A further clue to the importance of the River Ure perhaps remains in the name of the river. It is thought that Ure is derived from the Celtic word isure meaning “holy one”, a name reflected in the name for the nearby capital during Roman times – Isurium Brigantia. It should also be remembered that Ur is thought to be the name of one of the oldest gods known – the origin of the name for the ancient city of Ur in modern Iraq.

Thornborough Cursus

At some point in the latter half of the fourth millennium BC, Neolithic people built at least one cursus monument at Thornborough.

At some point in the latter half of the fourth millennium BC, Neolithic people built at least one cursus monument at Thornborough.

A cursus monument is a giant rectilinear enclosure – a huge cigar-shaped Earthwork structure, bounded by a slight ditch and a slight bank – almost like an exaggerated Roman road. The cursus was 1.2km long. 43m wide and ran from the River Ure towards the River Swale.

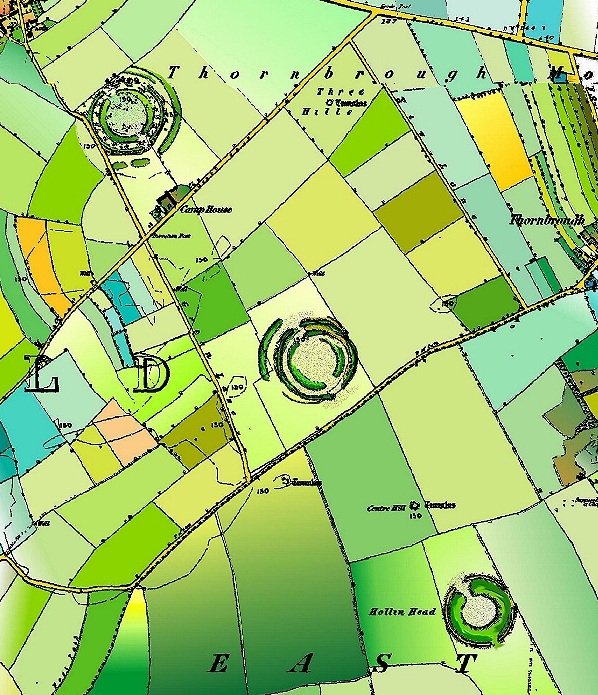

Image: Cursus Monuments at Thornborough, after Harding.

It is possible that more of the cursus remains underneath the village of Thornborough. The above diagram shows two further monuments, the Northern Cursus and the Eastern Cursus. These have yet to be confirmed by excavation.

Scorton Cursus

At the same time as the cursus monuments at Thornborough were being created, another much larger cursus was constructed some 12 miles to the north at Scorton, close to Catterick.

Again this cursus is close to a river, this time an elbow in the River Swale.

This cursus was 40m wide and 2.3km in length.

Together, the cursuses of Thornborough and Scorton are the only such monuments in the whole of North Yorkshire, and already the

Image: Scorton Cursus. After Topping.

place that was to become the Sacred Vale was being mapped out.

These monuments represent the first ceremonial complex built within the Swale-Ure plateau, part of a new and widespread phenomenon of monumental building that was spreading throughout the British Isles.

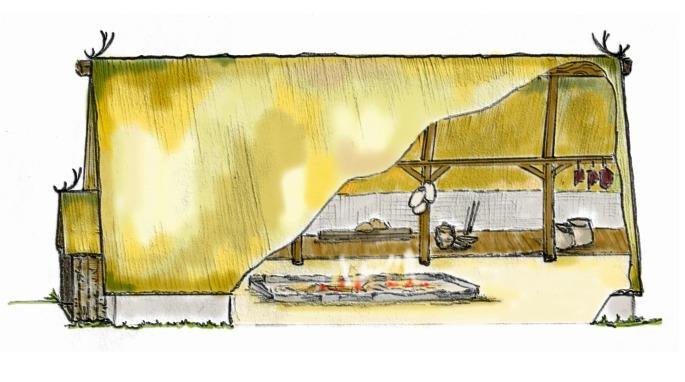

Image: Central Henge and Cursus at Thornborough. The Cursus can just be made out as two parallel crop marks running alongside the road and under the henge. English Heritage.

Cursuses are enigmatic monuments. They are often found in the many river valleys that run up and down the length of Britain. The physical remains are typically visible today only as crop marks.

Cursus monuments were very long and thin rectangular Earthworks, varying in length from 250 m to several miles, yet in width they seldom exceed 40-100m. They were constructed by digging a shallow ditch that defined the whole of the cursus area. The earth extracted was typically placed outside the ditch, creating a low circumnavigating earth wall. Sometimes earth was also piled up in the area enclosed by the ditch, creating a slightly raised plateau. Cursus monuments were often built with extreme accuracy; the length of the monument often being so straight as to rival the best Roman road.

Image: The pyramids of Giza – Possibly aligned to the constellation Orion?

One aspect that has often been emphasised about cursus monuments is the notion that they are processional ways – places where people were congregating, perhaps moving up and down them as part of a required ritual, as part of their religious practice. This would seem to make sense at Thornborough.

During the early Neolithic the main cursus at Thornborough would have been sited between two very marshy areas. The area to the south would have been the graded river channels of the River Ure, whose course would probably have been different to that which we see today. To the north there is the possibility of a marshy area at this extent of the cursus. So we have a piece of land, two kilometres wide and along that strip of land the cursus monument is built – linking the rivers – perhaps underlining a symbolic relationship between those two route-ways.

Similarly, at Scorton there is also a water association. This time the Cursus may have linked two glacial lakes, one to the south-east, the other to the north-west. It may also be that there is also a symbolic connection with the Swale.

It is likely that during the Neolithic period the region surrounding the Swale held many drying up glacial lakes.

Cursus monuments elsewhere tend to link in with or refer to natural features, Thornborough is a good example of this – its western end is very close to a bend in the River Ure, its eastern end is aligned on the northern Scarp of the Hambledon Hills as well as travelling towards the River Swale (it is not clear that this cursus actually stopped at the village of Thornborough, where we see it today, but this may well have travelled even further towards the River Swale).

It may well be that the main cursus at Thornborough reflects a route between the rivers Swale and Ure, perhaps an early trade route that cuts across the rivers to head directly east rather than follow them to their terminus at the Humber Estuary. This notion may show a significance in terms of the relationship between early trade routes and religious development.

A Link To Orion?

It would appear that the cursus at Thornborough has certain astronomical properties; work performed by Dr Jan Harding of Newcastle University has suggested that the cursus may be aligned towards celestial or astronomical events. Dr Harding has suggested that the eastern terminal of the cursus is aligned to the midsummer sunrise; the western end is aligned towards the setting of the main belt of the constellation of Orion.

This relationship with celestial events is also true of a number of other monuments of the British Isles, including cursuses and Henges. It may well have an origin based on practicalities as much as any mysticism.

To try to take the mystery away from this monument and place its construction as perhaps a natural outcome of human activity, it may be appropriate to think about the development of early trade and the effect this may have had on the environment at Thornborough.

If we accept that trade was a growing phenomenon (which will be discussed later), primarily a result of the increasingly settled farmstead lifestyle of the Neolithic people, then it is likely that trade will have been a seasonal aspect of life. It would make sense to have a farm fully manned during the growing season and until harvest time, but immediately after the harvest there is a period in the late Summer/early Autumn where for a couple of months the weather is still reasonably good, and the rivers are still low in water following the drought of Summer.

If we accept that trade was a growing phenomenon (which will be discussed later), primarily a result of the increasingly settled farmstead lifestyle of the Neolithic people, then it is likely that trade will have been a seasonal aspect of life. It would make sense to have a farm fully manned during the growing season and until harvest time, but immediately after the harvest there is a period in the late Summer/early Autumn where for a couple of months the weather is still reasonably good, and the rivers are still low in water following the drought of Summer.

This time of the year is ideal for early farmer traders to travel to trade for items not locally available.

If we follow this theme further and accept that rivers played a major role with early trade – providing food and an added opportunity to ease transportation problems. Then there must have quickly sprung up overland linkages between rivers to allow trade in other regions.

It may be that at Thornborough this is precisely what happened – it became the preferred overland route between the Swale and the Ure, perhaps by way of an easy shortcut – the rivers merge about 8 miles downriver. This overland route would cut out some 16 miles or so of unnecessary travel.

If we assume that this was the case at Thornborough, that increasing numbers of people started passing through Thornborough to trade then it is not unreasonable to think that perhaps at some point the local people will have set up some form of trading post.

Perhaps here was a place where traders could rest and trade food and other goods to help them on their journey. Perhaps locals offered themselves as porters to help carry goods from one river to the other.

Taking this one step further, the additional wealth coming to the area due to trade will have made Thornborough a local centre – somewhere to come and catch the passing traders and a place of enhanced wealth and importance in the local area, thanks to that trade.

This background would mean that when the people of the Vale of Mowbray built their first monument – the cursus – Thornborough was the obvious site. It was visited by a great many people compared to other places

in the area, and was a source of significant extra wealth for the region. In capitalist terms, it was also the obvious place for a local “authority” such as a religion to gather income, either by donation or taxation.

Image: Thornborough Henges, English Heritage.

Image: Neolithic Village, Joanne.

Just as Thornborough sits on a possible trade route, Scorton sits close to a historic river – crossing at Catterick. This has been the favoured crossing point for the last two thousand years, and it would hardly be surprising if its Neolithic equivalent were not close by.

This trade hypothesis also holds a claim to the particular alignment of the central cursus at Thornborough – The Orion Constellation.

The Orion Constellation appears at night sky towards the end of Summer. Perhaps as Thornborough’s fame as a good place to meet and arrange trades for the forthcoming season spread, the time to meet was expressed as a particular astronomical event that happened once a year – the rising of Orion?

Image: Thornborough Central Henge. (G. Chaplin)

The Neolithic period was one of transition from a nomadic existence to one of farming. Settling down had disadvantages in so much as a farm ties the labour to a fixed location. This meant that for significant periods of the year it would be difficult to release people to fetch resources that were not available locally.

Perhaps the early farming communities found that there were certain periods of the year that were best for trade. During the summer months, most labour would have

been best kept close to the settlements – to tend the crops and animals and to help with the harvest.

There is a relatively short period, after the crops have been gathered and before the onset of the harsh Winter weather when the rivers are low and the weather is still relatively clement, when a significant proportion of the workforce could be released for trading activities. The beginning of this period is coincidental with the rising of Orion. Perhaps this was a time when people chose to trade, and the relationship with Orion was recognised with the building of the cursus at Thornborough.

A further point that should not be overlooked is that autumn is an ancient time for celebration – the harvest festival of later years no doubt began life perhaps even before the Neolithic period. Again, the link between this time of year and the appearance of Orion tends to suggest that this cursus may have been linked with a very early harvest festival.

It is likely that the other cursus monuments at Thornborough (should they be confirmed as such) will have relationships with events at other times of the year. In spring, another possible trade window opens before the main growing season has begun. It is likely therefore that of the other cursus monuments in the area, either here or at Scorton to the north, one may be connected with an astronomical event related to this time of year.

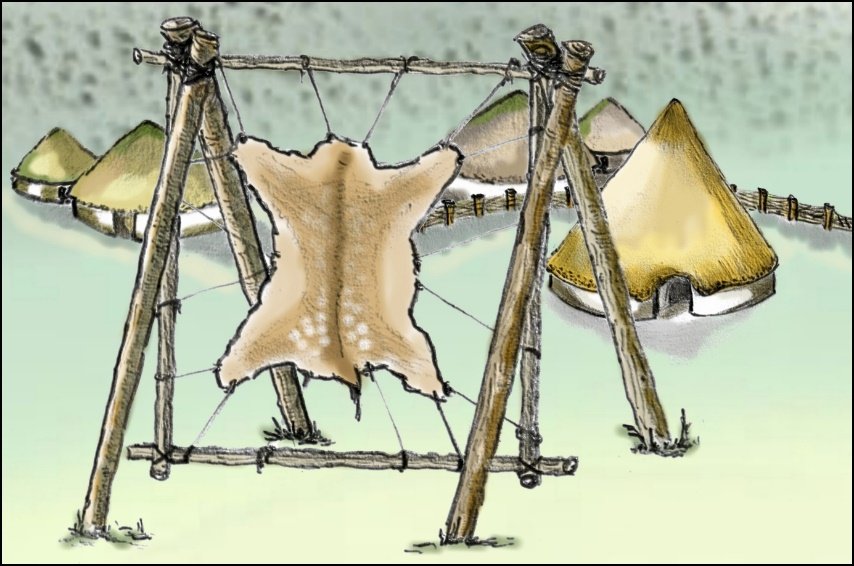

Image: Central Cursus at Thornborough. Joanne.

However, care should be taken when looking at these ancient monuments. Whilst the cursus at Thornborough seems to give good reason to assume a relationship with Orion, other monuments may not have the same trade-based linkage. This is after all, a very poorly understood period, one that we continually realise is more complex than has been previously assumed.

Building a Cursus

An interesting diversion may be to discuss the economic impact of building a cursus. This may help gain some sort of understanding as to the level of organisation required to create a cursus, as well as perhaps the regional power-base of the people who built it. This exercise will simply try to work out the minimum effort required so we can gain some perspective on the effort required to build these monuments.

Let us assume that one man could dig 15m of ditch per day. Remember, this was the time before metal – tools had to be fashioned from wood, stone or animal parts (horn, bone etc.). Let us also assume that the population density of the time was 1 person for every square kilometre. This equates to a population estimate of approx. 100,000 in Britain, which is in line with many estimates.

Let us also assume that construction of the monument was done as a long-term shared labour exercise, using one day per week donated labour from every able body.

If these uneducated guesses are correct, and we know that the perimeter of the Thornborough Cursus is 2,700m, then we could calculate that it took 180 days of human effort to build it – ten people working one day per week could build it in eighteen weeks.

If we then assume that for every able-bodied person, there are ten others who were unable to participate due to other commitments, then this works out to a minimum population needed of perhaps just 110 people to build this monument. This equates to a 10 x 10 km region of land under a single leadership to command the manpower to build this monument.

This rough-and-ready calculation can in no way be relied on, but the geographic area suggested does fit favourably with the concept that this was a monument of local/regional importance, built by local people without outside help.

The Cursus at Scorton would have required perhaps twice the manpower and whilst together the two mark out the area that would develop into what we call the Sacred Vale, it is likely that both the Scorton and Thornborough Cursuses were individually conceived local monuments, marking out a place of importance to local people.

It should also be noted that in the calculation we have ignored the effort required to clear the area of trees and also any wooden structural work – most cursus monuments are known to have had wooden post alignments associated with them – either in the ditch or within the enclosed space.

Whilst it is difficult to draw too much information from the little we know about these structures, it is clear that around 3,500BC a means of organising a large construction project existed, the technology to plan very long straight lines in the landscape existed, and sufficient excess of food enabled people to be taken away from food production to carry out such projects.

Whilst the construction of the cursus was not a massive effort for the people of the Vale, it was nonetheless a significant investment in resources,

including the set aside of land for non-productive use. Perhaps the construction of the monument was in itself an exercise in establishing a tribal identity?

Cursuses are more difficult to explain in terms of practical purpose. They were a monumental construction that took the combined effort of a significant section of the local community. Cursuses have no known practical advantages to the communities that built them, other than a statement of organisation and control. The development of these monuments throughout the British Isles shows that this was a widespread phenomenon. Given the proximity of the Cursuses within the Sacred Vale to burial monuments and other later monuments of religious significance, it is probably best to see the primary function of the cursus as being religious.

So it can be seen that at Thornborough and Scorton, during the Later Neolithic period, there were two giant processional ways that cut through the landscape, these referenced natural features in a way that suggests it was a monument dedicated to some form of religious activity – part of the ritual life of the people who visited and lived in the Sacred Vale.

The building of the cursus brought about changes in the way of life at Thornborough. Increasing numbers of people were making wider use of the landscape, Thornborough was starting to become a destination – not just a good place to pass through.

The cursus complex at Thornborough was part of a wider and more complex landscape. This is borne out by the results of the extensive field-walking surveys that have been performed since 1994 by Newcastle University. These surveys were carried out with a specific view to locate and map the distribution of worked flint.

The Evidence from Flint

Worked flint is a useful indicator of the levels of occupation during these ancient times when it was extensively used to create tools. Flint can be worked by a process called knapping, this creates sharp flakes that can be fitted with wooden handles to form various cutting implements.

Flint was the most important source of sharp tool material from far into the Stone Age and continued to be useful even after metals were discovered in the Bronze Age. Over time, the techniques used in knapping became increasingly refined and as a result, flint tools of differing styles can be dated with reasonable accuracy.

Field-walking allows flint tools and waste fragments brought to the surface by ploughing to be gathered for analysis. Once dated, the level of concentration and type of wear seen on these flint tools can reveal details such as potential settlement sites, industrial (tool production) areas and even the duration that a site was lived in.

Thanks to Newcastle University’s field walking project at Thornborough, a picture of potential occupation and settlement in the area surrounding the henges has been revealed. Based on this, it is possible to say that during the time when the Cursus was in use there was a notable rise in the number and spread of flint in the region compared to previous times.

This evidence indicates that the cursus was acting as a magnet for people – the numbers of people coming to Thornborough was increasing. This compliments the

picture of the cursus being a tribal ritual centre – people were coming, descending on this landscape, living around this ceremonial complex, undertaking ritual activities and then probably moving on to other locations.

Image: The remains of Hutton Moor Henge, Ripon.

The First Rituals at Thornborough?

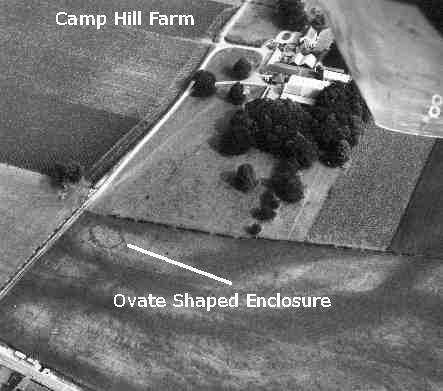

There is the distinct possibility that people were choosing Thornborough as a place to perform rituals related to the burial of their dead. Identified by aerial photography, and later excavated by Dr Jan Harding, is an oval-shaped enclosure located close to the eastern end of the main cursus monument at Thornborough. This was identified as the remains of a long mortuary enclosure.

From evidence found elsewhere, it is suggested that these long mortuary enclosures are linked with the treatment and the deposition of the dead during the Neolithic period. This indicates that the people who came to Thornborough were not just visiting the cursus and performing rituals upon it, but were also performing activities related to the deposition of human bones.

Furthermore, a Barrow excavated during 2003 by Dr Jan Harding was shown to be a burial mound dating from the same period – Thornborough was beginning to be a place where important people were buried and religious ceremonies were observed.

This is the brief picture that can be seen from the archaeology of the area for the fourth millennium BC; a fairly modest monument complex, not untypical of many such complexes located all over the British Isles – it is overshadowed in size by the nearby Scorton cursus for example, which was a mile longer (however the end of the Thornborough cursus has not been located).

Image: The ovate mortuary enclosure at Thornborough. English Heritage.

Image: Thornborough Henges; A beautiful past. G. Chaplin and Joanne.