Contents

- 1 Empathic Archaeology: Building and Breaking Straw Men for Deeper Understanding

- 2 The Active Imagination in Archaeology: Building the “Straw Man”

- 3 The Value of the Straw Man: A Flexible Tool for Exploration

- 4 The Importance of “Testing” the Straw Man in the Field

- 5 Imagination as a Tool for Empathy, Not Fantasy

- 6 Why the Collapse of the Model is Crucial

- 7 Conclusion: Empathic Archaeology as a Dynamic Process

Empathic Archaeology: Building and Breaking Straw Men for Deeper Understanding

“It’s like trying to psychoanalyse an imaginary alien in your mind, and hoping some of those wild ideas make sense out in the field”— A quote which beautifully encapsulates the challenge and creativity at the heart of empathic archaeology. It highlights the active imagination required to understand ancient peoples who may seem entirely foreign to us, and the constant process of refining or discarding our interpretations in response to new evidence.

At first glance, the idea of psychoanalyzing an “imaginary alien” might sound outlandish, but it perfectly mirrors the approach many archaeologists must take when trying to understand ancient cultures. These cultures are far removed from our own in time, and often in social structure, belief systems, and material culture. To bridge the gap between the modern researcher and these ancient peoples, we must use a form of active imagination, thinking creatively about how they might have thought, felt, and acted.

The Active Imagination in Archaeology: Building the “Straw Man”

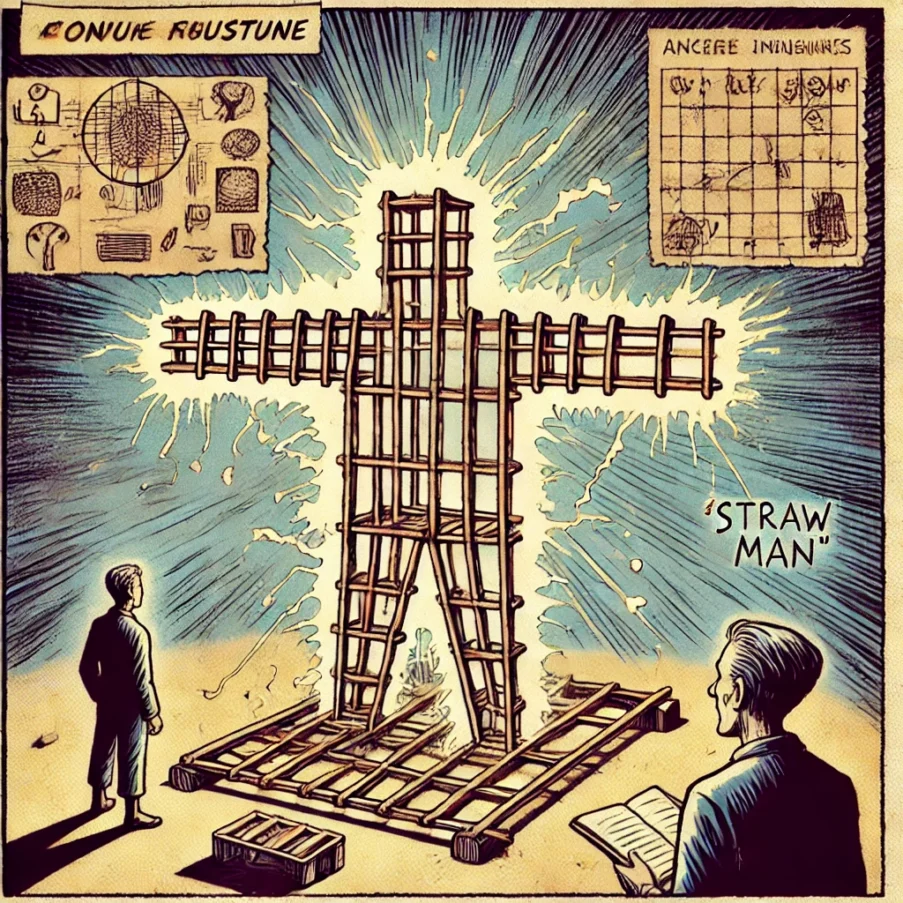

The idea of building a “straw man” is a useful metaphor here. In the context of empathic archaeology, a “straw man” represents a provisional, imaginative model of the ancient people you are trying to understand. This model is, at its core, speculative and may be completely wrong—but it serves as a starting point for exploration. Just as a straw man is deliberately constructed to resemble an argument or concept that can later be tested and torn down, the empathic archaeologist creates a mental construct of the people or society they are studying, based on available evidence.

For example, when studying an ancient civilization, archaeologists might imagine their social structures, motivations, and worldview in the following way: “What might a member of this society have believed about life after death?” or “How might they have viewed their relationship with the natural world?” These speculative ideas, though speculative, are built upon data from artifacts, rituals, and ethnographic analogies. The archaeologist then tests these ideas against what they observe in the field.

This process of constructing an imaginative model—the “straw man”—is crucial for empathic archaeology. It’s a method of entering into the world of the ancient peoples, putting yourself in their shoes, and allowing the evidence to challenge and refine your understanding of their experiences.

The Value of the Straw Man: A Flexible Tool for Exploration

The key to this process is flexibility. Just as a straw man can be knocked down and rebuilt, so too can our understanding of the past be constantly revised as new evidence is uncovered. By using imagination to create a hypothetical model, archaeologists are giving themselves a conceptual framework through which to view the evidence. However, they must be open to the fact that this framework may collapse entirely once they test it against new data.

This is why empathic archaeology requires both creativity and intellectual humility. The creation of a straw man allows archaeologists to actively engage with the unknown, but the subsequent collapse of the model—when new evidence suggests a different interpretation—is equally important. Each time a model breaks down, a breakthrough is achieved, leading to a deeper understanding of the people being studied.

For example, early archaeologists studying ancient burial sites might have imagined that elaborate burial goods indicated an aristocratic social structure. However, as more evidence was uncovered, such as the presence of similar goods in the graves of people from different social classes, the original straw man (the idea of a strictly hierarchical society) would need to be adjusted. Perhaps the original idea of burial goods as status symbols was not entirely correct, and instead, the goods had symbolic or ritual significance, challenging and enriching the model.

The Importance of “Testing” the Straw Man in the Field

The fieldwork phase is where the true test of this imaginative process occurs. Just as a psychoanalyst might evaluate the validity of their theories by observing the patient, an archaeologist tests their models by examining the real, physical evidence. The “alien” analogy helps highlight the complexity here. When you’re attempting to understand a culture so distant from your own, you’re, in a sense, studying a kind of “alien.” The ideas that come to mind may seem bizarre or far-fetched—much like those alien ideas—but they are grounded in the best available evidence at the time.

A hypothetical example could be the interpretation of ritual practices: archaeologists might create a model that suggests certain artifacts were used in sacred rituals, with the “alien” assumption being that these people were deeply spiritual. They might build this model based on certain types of pottery or ceremonial objects found in specific locations, and begin imagining how these artifacts might have been used in a ritual. But when they test this hypothesis, it could be refuted by new evidence, perhaps showing that the artifacts were used for practical purposes and had nothing to do with ritual. The collapse of this model then provides crucial insight—it’s not just a failure, but an opportunity to revaluate and build something more refined.

Imagination as a Tool for Empathy, Not Fantasy

It’s crucial to note that this imaginative process is not about making up wild, unfounded ideas or letting fantasy take over. The “alien” metaphor is not an invitation to indulge in pure speculation. Rather, it is a method of creative thinking that works within the boundaries of evidence. Empathy requires imagination, but that imagination is grounded in the data and informed by research. This is where critical thinking comes in: the need to remain vigilant about the limits of our models and to test them rigorously against new findings.

It is also essential to recognize the difference between empathy-based imagination and wishful thinking. Empathy in archaeology is about understanding a worldview from the inside out—not projecting our own desires or preferences onto ancient peoples. An archaeologist’s imagination is not a blank canvas but a tool for integrating diverse strands of evidence, historical context, and comparative analysis.

Why the Collapse of the Model is Crucial

The beauty of this process lies in the constant recalibration. Every time a hypothesis (or straw man) collapses, it refines the understanding and brings us closer to a more accurate representation of the ancient world. The collapse of a model isn’t a failure; it’s an essential part of the scientific method. Each failure exposes new questions, directs attention to overlooked data, and leads to new perspectives. This iterative process of creation and destruction is fundamental to developing a deeper understanding of the past.

For example, in the study of prehistoric art, an initial theory might be that cave paintings were created for ritualistic purposes. As new evidence from similar sites emerges, or as more precise analyses of the paintings are made (perhaps revealing that some caves were only used as temporary shelters or have no other signs of ritual activity), the hypothesis begins to break down. This forces researchers to think in new ways about the significance of the art, perhaps considering it as a means of communication or storytelling rather than a purely ritualistic practice.

Conclusion: Empathic Archaeology as a Dynamic Process

Empathic archaeology is not a static process; it’s dynamic and constantly evolving. It requires the active imagination of researchers to build tentative models or straw men, but it also requires an openness to having those models tested, challenged, and even shattered. Every collapse of the model is an opportunity for a deeper breakthrough—a step closer to understanding the humanity of those who lived long ago.

By embracing this approach, archaeologists can continually refine their understanding of the past, driven by creativity, intellectual humility, and a commitment to uncovering the truth. It’s an iterative, imaginative, and rigorous process that bridges the gap between the present and the ancient world—one breakthrough at a time.