The Goddess Brigantia

Historical Background On The ‘Exalted One’

Tina Deegan

Brigit was one of the most popular, and widely worshipped, goddesses of the Celtic-speaking peoples. Brigit, which is Old Irish for “The Exalted One”, is just one of the variant spellings for this native goddess. Her name can also be spelt as Brighit, Briid and Brigid.

Caesar mentioned Minerva and the insular evidence of the British Isles highlights a Minerva type goddess important within these isles: ‘the exalted one’. Known as Brigantia from the Roman inscriptions in the north of England where she was the tutelary goddess of the Brigantes tribe(s), some of the iconography has ‘victory’ imagery. This goddess has been identified as identical with the Gaulish goddess Brigindo and also linked with Brigit, the pre-Christian Irish goddess who was linked with fire, smithing, fertility, cattle, crops and poetry.

She is usually believed to be the same goddess as Brigantia for Brigit is cognate with that name (or its’ pre-Roman form of Briganti). Brigantia, meaning “High One”, was the tutelary goddess of the confederation of Brythonic tribes called the Brigantes who were based in the north of the British Isles (very approximately equating to the modern north of England). Ptolemy also mentioned the Brigantes as being within southern Ireland. Yet, this goddess is not only found in the Insular cultures for inscriptions of another goddess, cognate with Brigit and Brigantia, called Brigindo, have been found in what was eastern Gaul.

John Koch has suggested (1) that, in the same way as there may have been a mortal high priestess at Brigit’s cult centre in Kildare in Ireland, there may have been a high priestess of Briganti in Britain and Cartimandua is an example of this. She was a queen of the Brigantes in the early Roman period of British history. He further supports this concept by considering the male leader of the Brigantes. Binchy has shown the derivation of the Welsh word for king, brenin, as being from brigantinos or “consort of the goddess Briganti” which originally referred to the male leader of the Brigantes.

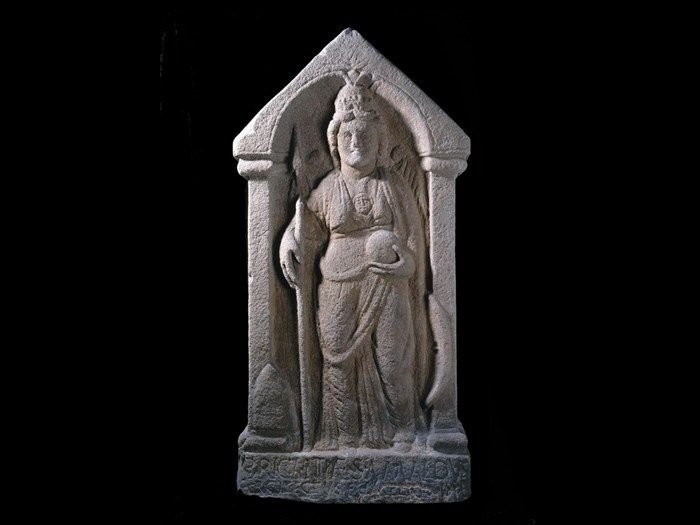

A Romano-British carving survives of Brigantia and was found at Birrens in southern Scotland. She wears a crown and has a face in the centre of her chest: symbolism which links her with the classical goddess Minerva (the face being the Gorgon’s head in classical terms). She also cradles a spear with one arm and cradles a globe at her waist with the other hand. This is symbolism associated with the Roman goddess Victory.

The consideration of the nature of the Pre-Christian Irish goddess, Brigit, is complicated in that our surviving evidence comes from later Christian writers. Also, there is no surviving pagan imagery as Ireland was not conquered by the Romans, which might have led to some contemporary stone carvings or inscriptions as in Britain.

A couple of the earliest works, which specifically refer to the pagan goddess are the Lebor Gabála Érenn, a medieval work of pseudo-history which incorporates the old gods and goddesses, and also Sanas Chormaic, a glossary written about 900ce by Cormac mac Cuilennáin who was both bishop and king. The Lebor Gabala describes Brigid as “the poetess” or banfili. And the daughter of the Dagda whilst Cormac’s Glossary also refers(2) to her as the daughter of the Dagda but says she was one of three daughters called Brigit. She was the poetess and a woman of wisdom whilst her sisters were the physician and the smith.

Genealogy was significant to the Irish, for the basic family unit within the law was the fine : this was the surviving family to six generations. The recitation of a royal claimants’ genealogy was an integral part of the Gaelic coronation (as shown in Scotland). So it is notable she is one of the Tuatha Dé Danann, or ‘the people of the goddess Danu’ who were the Pre-Christian pantheon of Ireland, and also that her father is the Dagda, the ‘good god’ in the sense of skilled rather than as a moral description. He was a most important god to the Old Irish, he was known (amongst other things) by the titles “Father of All” and “Lord of Great Knowledge”.

She is described as married with children in a few tales. One account is where she is married to Bres (“The Beautiful”) and they have a son Ruadan who was killed in battle. Brigid went onto the battlefield to mourn for him and this was said to be the first keening (from caoine or “lament”) in Ireland. Bres is the son of Ériu (or Eri) by a Fomorian king, and he briefly takes the kingship of the Tuatha Dé Danann when Nuada loast an arm, but was exceedingly mean and oppressive and was deposed. After being captured in battle, Bres saves his life by advising the Tuatha Dé about agriculture. There is another account4 where she is said to be married to Tuireann and had three sons: Brian, Iuchar and Iucharba. In the Lebor Gabála Érenn these are listed as the “three gods of the Tuatha Dé Danann” though little is known of them as gods.

Modern linguistic analysis has shown Cormac’s analysis of Brigit’s name, i.e. as being from breo-agit or “fiery arrow”, to be wrong, but I am uncertain whether this is a part of the erroneous etymologies he used from Isidore of Seville or whether it was from some lost source which contained contemporary pagan imagery about her.

Another source of information about the goddess, though also a complicating factor, is details from the life of the (approximately) fifth century Christian Saint Brigit and the folklore associated with her. It is widely accepted that this most important female saint in Ireland has assumed some aspects of, and likely lore from, Brigit the goddess. But assumptions or deductions have to be made as to what about Saint Brigit is an inheritance from the pagan goddess. One likely indicator is that the saint’s feast day is 1st February, Lá Fhéile Bríde, which happens to be the same day as the old Pre-Christian feast of Imbolc.

There are also variant spellings associated with the saint such as Bridget (especially popular on the Isle of Man), Brigid, Bríd, Bride and Brighid. There is also a Breton saint, Saint Barbe, who is also believed to be derived from a Pre-Christian fire goddess.(3) She was the patroness of firemen. Though, unlike St. Bridget, she was venerated on the last Sunday in June.

Endnotes

1. John T. Koch (ed.) with John Carey, The Celtic Heroic Age, (Celtic Studies Publications, USA 1995), p.39

2. As cited in the website of Ord Brighideach (https://members.aol.com/gmkkh/brighid/ob.htm May 1999)

3. James MacKillop, Dictionary of Celtic Mythology, (Oxford University Press 1998), p. 30

4. As quoted by Peter Berresford Ellis, A Dictionary of Irish Mythology, (Oxford University Press 1991), p.49

Additional Sources

Séamas Ó Cáthain, The Festival of Brigit: Celtic Goddess & Holy Woman, (DBA Publications 1995)

Miranda Green, Celtic Goddesses, (British Museum Press 1995)

Dr. Daithi O hOgain, Myth, Legend & Romance: An Encyclopaedia of the Irish Folk Tradition, (Ryan Publishing 1990)

Bernard Maier (Cyril Edwards trans.), Dictionary of Celtic Religion and Culture, (Boydell & Brewer 1997)