Celtic Heads

Celtic Head from Witham, 2nd c B.C. (British Museum) "Celtic" carved heads are found throughout the Read more

Timeline 60BC – 138AD

This timeline is focussed on the British Celtic culture and those cultures which had influence on the British Celts. It Read more

Cartimandua

Yorkshire, and much of northern Britain was also ruled by a queen, the most powerful ruler in Britain in fact. Read more

Caratacus

Caratacus was highly influenced by the Druids, and both he and his brother Togodumnus were among the leading lights of Read more

Cerialis Petillius

Quintus Petillius Cerialis Caesius Rufus was the son-in-law of Vespasian Cerialis and became Governor of Britain in AD.71; his instructions Read more

Julius Caesar

Ask anyone to name a famous Roman character, and the name of Julius Caesar is sure to be the most Read more

Vespasian

Born in the year 9 at Reate, north of Rome, Vespasian was the son of a tax collector, Flavius Sabinus Read more

Augustus

Suetonius wrote of him: He was very handsome and most graceful at all stages of his life, although he cared Read more

Claudius

Tiberius Claudius Nero Germanicus was born Lugunum in 10 BC, the youngest son of Nero Drusus, brother of Tiberius. He Read more

Celtic Gods

Many Celtic deities seem to have been associated with aspects of nature and worshipped in sacred groves. Some appear in Read more

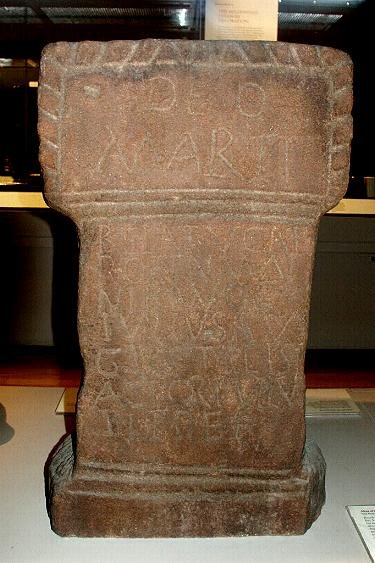

Roman Altar Inscriptions to Brigantia

Goddess Brigantia

Votive inscriptions to the Goddess Brigantia have been found in the North of England using four names: Caelestis Brigantia, Nympha Brigantia, Brigantia Augusta, and Victoria Brigantia. In this report I review what is known about them, and how this knowledge can help us understand how the Romano-British viewed the Goddess.

Adel: Altar by Cingetissa. RIB 630

The Goddess Brigantia

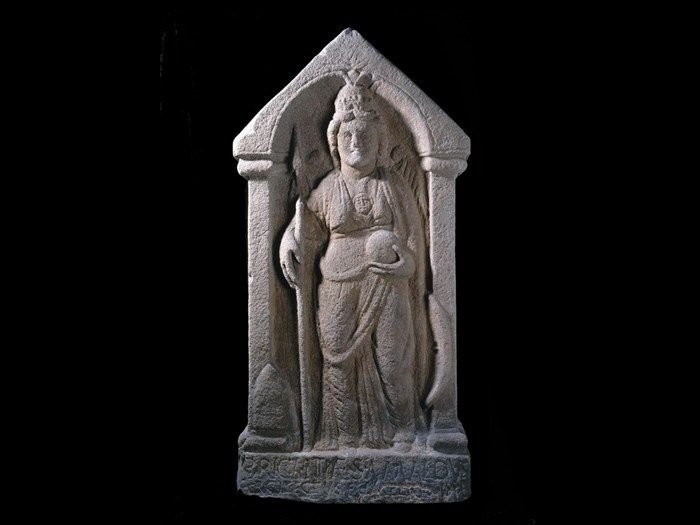

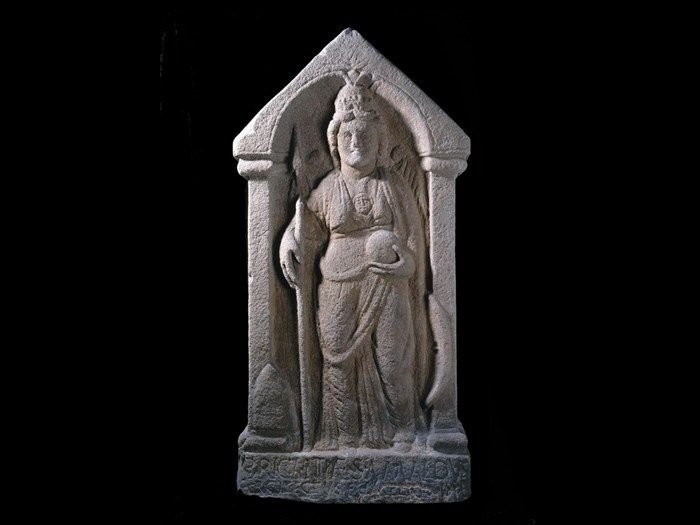

Birrens: Figure in gabled relief by Amandus arcitectus. RIB 2091 (49) (Above image)

South Shields: Altar by Congeniccus. RIB 1053

Bath: There is a curse tablet dedicated to A God called Bregneus, which has been loosely equated with the Brigantes and Brigantia

Caelestis Brigantia

Corbridge: Altar by G. Julius Apolinaris, centurion of VI Victrix, his name, rank and unit replacing someone else’s or else recarved to make a correction. RIB 1131 (with Jupiter Aeternus Dolichenus and Salus). See also Brit. xxvi (1995), 380, no. 7 for another possibility.

Nympha Brigantia

Castlesteads(?): Altar to Nympha Brigantia in honour of Caracalla and his divine house by M. Cocceius Nigrinus, [pr]oc(urator) Aug(usti) n(ostri), ‘procurator of our Emperor’, between 212-17. RIB 2066 (with Domus Divina)

Victoria Brigantia (Victorious Brigantia)

Castleford: Altar by Aurelius Senopianus. RIB 628

Greetland: Altar by T. Aurelius Aurelianus, magister sacrorum, in 208. RIB 627 (with Numina Augustorum)

Brigantia Augusta

Slack: There is a Altar dedicated to Bregans, currently interpreted as representing a male aspect of Brigantia. But it is tenuous without further evidence.

Discussion regarding the implications of the names used for Brigantia

The variations of the names used for Brigantia in Roman inscriptions—such as Caelestis Brigantia, Nympha Brigantia, Brigantia Augusta, and Victoria Brigantia—reflect the complex syncretism between the native Celtic goddess Brigantia and the Roman pantheon, alongside shifts in religious and imperial ideology. These variations offer insights into how the Romans adapted and integrated local deities within their own religious frameworks, often reshaping or aligning them with Roman concepts.

Here is a breakdown of the implications of these different titles:

Caelestis Brigantia

Meaning: Caelestis means “heavenly” or “celestial” in Latin. This title for Brigantia aligns her with the Roman concept of the divine celestial sphere, suggesting that she was associated with the sky, the heavens, or divine power, which is a common Roman attribute given to various gods.

Implication: This title indicates a higher, possibly more abstract or universal role for Brigantia, aligning her with celestial or sky deities like Juno Caelestis (the Roman “Heavenly Juno”). It may reflect her transformation into a more Romanized or cosmopolitan deity, one that could be worshiped not only in specific local contexts but also in broader Roman religious practices. By emphasizing her “heavenly” nature, it elevates Brigantia from a local tribal goddess to a more universal divine figure, potentially linked to Roman imperial aspirations.

Nympha Brigantia

Meaning: Nympha refers to a type of female spirit or deity associated with nature, often linked to rivers, trees, and forests in Greek and Roman traditions. By using this title, Brigantia may be associated with natural, liminal spaces.

Implication: The title Nympha connects Brigantia with the ancient, elemental spirits of nature and suggests a more localized, nature-based role. This connection could have been particularly appealing in Roman Britain, where natural places such as rivers, forests, and springs were sacred to both the native peoples and the Romans. The term Nympha Brigantia might suggest that, in certain contexts, she was revered in more intimate, pastoral settings. It could also indicate a more nurturing, life-giving aspect of her character, emphasizing fertility and nature rather than warfare or victory, which are typically associated with Roman goddesses like Victoria.

Brigantia Augusta

Meaning: Augusta is a title used by Roman emperors and empresses, meaning “venerable” or “majestic,” and signifying imperial divinity or elevated status. The title Brigantia Augusta might imply that Brigantia was being equated with imperial power or was being revered as a goddess of the imperial family.

Implication: The use of Augusta implies that Brigantia had been elevated in status to a level befitting the imperial cult, perhaps as a patroness of the emperor or empire. This could indicate a shift towards state-sponsored religious practices where local deities were integrated into the imperial cult. The title might suggest an imperial policy of incorporating regional deities into the Roman pantheon as a way of legitimizing imperial rule by presenting the emperor as the earthly representative of the gods, with Brigantia acting as a supporter or protector of the empire.

Note: This extrapolation is made in the knowledge that the evidence to support this name suggestion, is reasonably tenuous.

Victoria Brigantia

Meaning: Victoria is the Roman goddess of victory, often depicted as a winged figure, symbolizing success in war and conquest. The title Victoria Brigantia combines the Celtic goddess Brigantia with the Roman concept of victory.

Implication: This fusion points to a Romanization of Brigantia, aligning her with the Roman goddess of victory. The combination likely reflects the role of Brigantia in the local religious system and her association with triumph, which was of great importance in Roman military culture. It suggests that Brigantia was viewed as not just a protector of the local tribes but also as a deity who could bring success and victory in battle, aligning her role with Roman imperial ideals. This shift might have been used to enhance the legitimacy of Roman power in the region, where victory was a central theme in both military and cultural contexts.

General Implications

Syncretism: These various names reflect the Roman practice of syncretism, where Roman deities and local gods were blended. The changing titles of Brigantia show how local deities were adapted to Roman religious ideas, incorporating elements of Roman imperial culture, nature spirits, and celestial powers.

Regional Variations: The choice of different titles might indicate regional or local preferences in how Brigantia was understood and worshiped. Different communities might have emphasized aspects of Brigantia that aligned with their specific needs—whether for victory in battle, protection in nature, or association with the imperial cult.

Elevation of Brigantia: Over time, the use of titles like Caelestis and Augusta reflects Brigantia’s elevation from a local Celtic goddess to a more cosmopolitan figure, one who could be worshiped in the broader Roman religious context, and even connected with the emperor’s divine authority.

Adaptation for Roman Worship: The Romans were skilled at adapting local gods into their pantheon, giving them Roman qualities and associating them with Roman virtues like victory, power, and imperial glory. This approach allowed for smoother integration of local populations into the Roman Empire, as it was easier for them to accept imperial authority when it was seen as consistent with their own deities.

Brigantia as a Triple Goddess and the Symbolism of Three-in-One

You may have a notion that Brigantia is a triple goddess, yet here we see four names applied to Brigantia here. From my work in spiritual circles. I understand that a collection of spirits that work together in unison form another, highest version of that archetype – The one that embodies all three. This notion is often lost in our interpretations. But here, it makes quite a great deal of sense. Let me explain:

In Celtic traditions, Brigantia is often conceptualized as a Triple Goddess, a deity represented by three distinct but interconnected aspects. This concept of the triple deity is a common motif in many cultures, reflecting a unity of three forces or manifestations that work together to form a singular, potent divine entity. The three faces or aspects can represent different parts of the goddess’s nature, like:

- Brigantia as a Warrior (the protector, the one associated with victory, success, and war),

Brigantia as a Healer or Nurturer (the life-giving, creative, and nurturing aspect),

Brigantia as a Wise or Prophetic figure (the teacher, the spiritual guide, the connection with the ancestors).

In this context, the Triple Goddess is more than just three separate roles; it’s a powerful spiritual unity of complementary energies, as well as a model for understanding the cyclical nature of life, death, and rebirth.

Augusta as the Symbolic One: The Hidden Fourth

Now, when one considers the idea of Brigantia Augusta—”Augusta” being a title often conferred upon the imperial gods, elevating them to a divine and revered status—the concept of a “hidden fourth” begins to make more sense. In this case, Brigantia Augusta could be seen as representing the symbolic, unifying force that binds the three aspects of Brigantia into a single, divine whole.

The term Augusta in Roman contexts denotes something venerable, majestic, or worthy of imperial respect. In the Roman imperial cult, the emperor was often associated with the divine and referred to as Divus Augustus, symbolizing the unity of all Roman virtues. By giving Brigantia the title of Augusta, the Romans may have been elevating her to the role of a supreme, unified force that transcends her individual aspects.

Brigantia Augusta may not only signify a singular divine form of Brigantia but also symbolically embody the concept of the three-in-one. She is the fourth, the invisible force that holds the other three aspects together. This “hidden fourth” could represent a deeper, more esoteric quality, such as the unity of body, mind, and spirit, or perhaps the balance between life, death, and rebirth, the cyclical nature of existence—concepts inherent in Triple Goddess imagery.

This aligns with the mystery religions and certain esoteric traditions in the Roman world, where the fourth element often symbolized wholeness, completion, or the divine unity that is beyond visible comprehension. The idea of a “hidden fourth” is also seen in other mythological systems, like the fourth dimension or the invisible axis that supports the visible three.

Hierarchy within Roman Gods

In terms of where these deities sit in the hierarchy of Roman gods, we can look at the Roman pantheon and see how the titles and attributes of Brigantia align with different categories of divinity.

Victoria Brigantia: Victoria, the Roman goddess of victory, was important in military contexts and could be considered among the major deities when it came to military and imperial triumphs. Placing Brigantia alongside Victoria could elevate her to a powerful, imperial status, especially in contexts where military conquest or imperial success was a key focus.

Caelestis Brigantia: The title Caelestis suggests a higher divine status, linking Brigantia to the heavenly or celestial sphere. This would place her among the more universally revered deities—those associated with the heavens or divine forces that transcend specific, localized religious practices. She could be seen as akin to gods like Juno Caelestis or Sol Invictus, who were worshipped for their broader, celestial powers.

Nympha Brigantia: As Nympha, Brigantia is perhaps relegated to the lower levels of the pantheon, aligning her with nature spirits or deities of specific places (rivers, trees, springs). Nymphs in the Roman system were considered minor deities or spirits connected to nature. This aspect might be seen as Brigantia’s more earthy and local manifestation, perhaps more accessible to the people but still significant in the broader spiritual landscape.

Brigantia Augusta: As Augusta, Brigantia would be among the imperial deities, occupying a position of reverence and authority akin to that of Roman gods like Apollo or Minerva, who were associated with both the state and the imperial family. In the context of imperial cults, a deity with the title Augusta is elevated to the highest ranks of divine veneration, suggesting that Brigantia’s imperial status was key to her acceptance within Roman society. We do, however, need to take care to bear in mind the evidence for this appellation is the weakest.

The Hidden Fourth in a Broader Context

The idea of a “hidden fourth” is not just an interesting theological speculation but also a potentially transformative aspect of how we understand the process of the Romanization of local Celtic deities. The Romans were adept at reinterpreting and reshaping local religious systems, which included not only integrating deities into their pantheon but also elevating them by giving them imperial titles like Augusta and Caelestis. In a sense, the Romans could have re-envisioned Brigantia as not just a Celtic deity but as a figure capable of embodying Roman virtues like imperial strength, military success, and cosmic power—all of which could be expressed through her hidden, unifying essence that encompasses both the three and the one.

Brigantia Augusta may be seen as the force that holds these aspects of Caelestis, Nympha, and Victoria together, representing the unifying divine essence that transcends individual forms. This interpretation could help us understand better, and see triple goddesses as actually being capable of understood to be the three, embodied within the one, in their most potent form.

The Birrens Statue of Brigantia: Are we seeing the full picture?

The Birrens statue was discovered at the Roman fort of Birrens, located in Scotland. It is a marble statue that depicts Brigantia, the Celtic goddess, in a form that incorporates Roman imperial iconography. It’s possibly Britain’s most important statue relating to the Goddess Britannia, As it seems to show her as some kind of equivalent local deity as Juno, plus a number of other Goddesses and levels of divine power. This is intriguing, as there seems to be little or no evidence of any female deity elsewhere being potentially paid this kind of honour.

However, I have to remind myself to keep my cool, remember I don’t really know anything, and take a look at the scant evidence, and what I dare extrapolate from it. Remember, I am no professional. I love making connections, looking that bit deeper. It’s part of the process to jump to a premature conclusion or two, just so they can be proven wrong later, and maybe, in so doing shed a little extra light on the subject.

Sometimes academic sources, can be difficult to navigate or too technical to understanding at first pass. Most people do not have the time to sift through sources and work out the cryptic meaning to the some commentary or report data itself, never mind it’s voracity. This was the case when I first tried to dig into the reasoning behind the current accepted interpretation of the Birrens Statue inscription:

“Sacred to Brigantia: Amandus, the engineer, by command fulfilled the order.”

On the surface, this sounds simple enough, but as always, I wanted to check the original source – What was the original Latin? I could not find this. But I did spot this discussion about the translation:

“imp · i, Clerk, suggesting imp(eratoris) I(uliani); imp · i, Hors., suggesting as an alternative imp(endit); imp · i, McCaul, suggesting imp(erante) i(psa) or [n]imp(hae) i(psius); im͡p · i, Gord. in pl.; imp, Grotefend, conj. i{m}p(sius); Henzen conj. imp(ensa) [s(va)] and quoting Mommsen’s conj. imp(eratum) [f(ecit)], which Hueb. accepts with reserve. imp, : The splayed m, at first ligatured to p, was corrected to imp. This can hardly be expanded as imp(eratoris), for the emperor would be cited as Aug(usti). It seems best to take it as imp(eratum fecit). In Germany dedications to the Matronae use the phrase ex imperio ipsarum (CIL xiii 7904, 7905, 7906, 7925), so imp. may have been mistakenly drafted for ips(ius) the command will have come from the goddess R.P.W.”

Now I’m no expert on Latin, but what jumped out at me, was that the term “IMP I” seems to have been in the original text, but was no longer mentioned, either in the translation, or in a sidenote stating that it had been removed, and why, in plain English. So people like me can understand. Especially when the reference links include 70 year old Latin documents.

I could also see, that although they had referenced German Matronae inscriptions, they did not seem to have reviewed either the context of the inscription itself: The Birrens Statue. Neither had they referenced the other Roman Brigantia inscriptions.

I therefore decided to see what I could do to decipher this commentary, and retest those assumptions, including the symbolic meaning of the status itself, and the evidence from the other inscriptions. Plus a look at how this potentially new conclusion fits with Roman interactions with local deities fits with evidence from elsewhere.

Given that the visual symbolism of the Birrens statue must be central to the debate regarding the supporting context to the inscription, it’s surprising that this, in the least, was not mentioned. The discussion focused more on the inscription itself, leaving out important contextual details like the apparent Orb she is holding, along with a spear. These are all potential symbols of great power. Yet, this debate seems to have concluded that the Romans made a mistake, and ended up repeating a daily comedy of errors as they accidentally honoured Brigantia as potentially, the sacred consort of their emperor.

Let’s review the Birrens Statue

Objects in the Statue

-

Spear: The spear in the Birrens statue is a symbol commonly associated with both military power and authority. This is consistent with the idea of Brigantia being depicted as a protector and warrior figure. The spear was often used in Roman military iconography, symbolizing leadership and power, particularly in depictions of gods and goddesses connected to victory and protection (similar to Minerva, the Roman goddess of wisdom and warfare, who was depicted holding a spear). The Spear is also an important symbol of power for the local Iron Age people, as can be seen in such deities as Lugh.

- Orb: Brigantia seems to be holding a Orb parallels the Orb held by modern monarchs, and historically, those who held a Orb were understood to possess divine or inherited authority. The Orb symbolizes the right to rule, and its connection to Brigantia ties her to a higher authority—that of the Roman Empire. In this way, Brigantia could be seen as not only a local goddess but also a divinely sanctioned figure whose power could protect and legitimize Roman rule in the Britannic territories. Either that, or we should see other Goddesses, not linked to Brigantia but having similar status, recognised in their local area.

The Role of Symbols in Roman Imperial Cult

In the Roman context, the spear and laurel wreath are imperial symbols closely tied to the imperial cult and military victory. This type of iconography on local deities like Brigantia would have been part of the Romanization of local gods. The Romans often adopted and adapted native deities, blending them with their own pantheon, and this would include military symbols as part of the imperial cult to integrate local gods into the broader Roman imperial structure.

- Spear: The spear also represents military power. Roman gods associated with war, like Mars and Minerva, were often depicted holding a spear, a symbol of their authority in battle. Brigantia, shown with a spear, aligns her with these Roman military deities, further reinforcing her role as a protector and warrior goddess within the Roman imperial framework.

-

The orb (or globus in Latin) is a powerful symbol of imperial power in Rome and has a deep and evolving significance, both in Roman culture and in later periods, such as the Byzantine Empire and medieval monarchies. The orb itself, typically depicted as a spherical object held by emperors or other sovereigns, is associated with the idea of universal dominion, sovereignty, and cosmic order. The orb in Roman imperial iconography was frequently seen in depictions of the emperor, often in the hand of the emperor alongside other symbols of power, such as the sceptre or globe. Its significance evolved as a symbol of Roman authority, but the core symbolism remains tied to the concept of universal rule and divine legitimacy.

The Orb in Roman Imperial Power

The Orb as a Symbol of Universal Dominion

- The orb was frequently used as a symbol of the emperor’s sovereignty over the known world, particularly as Rome expanded its territory. The orb signifies the emperor’s rule over the Earth, encompassing the entire known world, which was considered to be under the emperor’s control.

- This aligns with the imperial ideology that Rome, under the emperor, ruled over the entire known universe, and the orb symbolized the totality of imperial power.

The Orb and the Concept of the Cosmos

- The orb also carried a cosmic significance. In Roman thought, the universe was often depicted as a sphere, a perfect shape that symbolized the harmonious order of the cosmos. Therefore, the orb in the hands of the emperor was also a reflection of his role as the divine guarantor of cosmic order.

- This connection between the orb and the cosmos would eventually influence later depictions of kings and emperors in the Christianized Byzantine Empire and medieval Europe, where the orb became a symbol not only of earthly dominion but also of the emperor’s role as a defender of divine order and God’s earthly representative.

The Orb and Roman Imperial Iconography

- The orb was often depicted alongside other imperial symbols. For instance, in Roman coins and sculptures, emperors are shown holding a sceptre in one hand and an orb in the other, signifying their combined authority over the military (sceptre) and the entire world (orb). This dual symbolism underscores the emperor’s role as both a military leader and a universal sovereign.

- The orb often appeared in representations of Augustus, Tiberius, and other emperors, emphasizing the idea of Roman world dominance. Over time, the orb became associated with imperial power itself, symbolizing the emperor’s authority over the empire.

Confirmation from Archaeological and Historical Studies

-

Brigantia’s Role in Roman Britain: As a local Celtic goddess, Brigantia was traditionally associated with protection, wisdom, and victory. After the Roman conquest of Britain, the Romans often syncretized local deities with their own pantheon. Brigantia’s association with victory and warfare through the laurel wreath and spear indicates her adaptation to the Roman religious framework, especially in relation to the imperial cult. This type of religious fusion is a characteristic feature of the Roman practice of interpretatio Romana, where local gods were associated with Roman deities to help integrate the local population into the Roman system.

-

Romanization of Local Deities: Romanization often involved the use of Roman symbols to elevate local deities. In the case of Brigantia, her adoption of imperial symbols can be seen as a way of giving her a broader, imperial significance, aligning her with the power and authority of the Roman Empire. Roman deities like Victoria (the goddess of victory) were central to the imperial cult, and the laurel wreath was a symbol used to represent imperial triumph. Brigantia’s use of such symbols places her within this context.

In the statue of Brigantia from Birrens, the objects she holds are pivotal in interpreting her symbolism:

Connection to Royal Symbols of Power

The objects in the Birrens statue—the spear and the orb—have clear parallels with symbols seen in the royal symbols of power, both in ancient times and in more modern settings. The spear, as a symbol of military authority and protection, directly connects Brigantia to concepts of sovereignty and leadership, much like how a monarch’s orb symbolize their right to rule.

-

Sovereignty and Power: Much like how modern royal families use symbols such as the crown (a sign of rulership and divinity), Orbs (symbols of control and governance), and the spear in Brigantia’s iconography position her as an authoritative figure whose power transcends her local tribal roots.

- Brigantia as a Higher Authority: The Orb is often used in royal iconography to symbolize the monarch’s divine right to rule. In both ancient and modern depictions of monarchs, the Orb signifies the sovereign’s authority and the divine or hereditary power they hold. The Orb is used by many ancient gods and goddesses as a symbol of their sovereignty and control over certain domains. For instance, in Greek and Roman mythology, gods like Jupiter is often depicted holding a Orb, signifying his governance over both the heavens and the earth.

The Symbolism of the Statue vs. the “IMP” Debate

The Birrens statue of Brigantia is a significant artifact that has been the subject of scholarly discussion, particularly concerning its iconography and the associated inscription. The statue depicts Brigantia holding a Orb and laurel wreath, symbols traditionally linked to imperial authority and victory. This portrayal suggests a syncretism between Brigantia and Roman deities such as Minerva and Victoria, reflecting the Romanization of local Celtic beliefs.

The inscription on the statue, which includes the title “IMP” (Imperator), has been a focal point of debate. Some scholars interpret this as an indication of Brigantia’s association with imperial power, while others view it as a standard honorific title. This debate underscores the complexities in understanding the extent of Roman influence on local deities and the nuances of religious syncretism in Roman Britain.

The commentary discussed earlier in relation to the interpretation of “IMP”, shows a series of interpretations regarding the abbreviation “IMP” and how it might be expanded. These interpretations are essential to understanding the inscription’s meaning and how it relates to the use of imperial symbols in the statue. Let’s break down the possibilities mentioned:

-

imp(eratoris) I(uliani) – This suggestion ties “IMP” to Imperator (a military title) and could reference Julius, possibly Julius Caesar or another figure. However, this interpretation would be unusual, as emperors are typically cited with their imperial title (Aug(usti)), rather than just “IMP”.

-

imp(endit) – This suggestion proposes IMP as part of the verb impendo, meaning “to dedicate” or “to make a vow.” This would imply that Brigantia or another divine figure is being dedicated or venerated, but this is somewhat disconnected from the Roman imperial context.

-

imp(erante) i(psa) – Here, the suggestion is that “IMP” could be expanded to “imperante ipsa”, meaning “the ruling goddess herself.” This interpretation aligns with the idea that Brigantia, as the divine protector, may have been associated with imperial authority or even military leadership in her own right.

-

imp(hae) i(psius) – This conjecture suggests IMP could stand for “imp(hae) ipsius”, referring to the command or will of the goddess herself. This interpretation hints that Brigantia is directly responsible for the dedication and, by extension, for the imperial connection. This could imply she was intervening on behalf of the imperial power, in keeping with the protective and sovereign role she plays in the statue’s iconography.

-

imp(ensa) [s(va)] – This interpretation, which seems to be quoting Mommsen, suggests IMP could refer to “impensa”, meaning “expense” or “tribute.” In this case, it could refer to the dedication of a statue or altar, possibly funded by the imperial treasury or as part of the imperial system.

-

imperatum – This suggests IMP could be shorthand for “imperatum”, meaning “commanded” or “ordered.” This might imply that the dedication was made under imperial command, reflecting the imperial connection but without directly associating the goddess with imperial status. Henzen’s suggestion of “imperatum fecit” might indicate that the dedication was completed under imperial authority.

Conclusion on the “IMP” Debate

- “IMP” as “imperatum fecit” seems to be the most widely accepted interpretation. This suggests that the dedication was commanded or sanctioned by imperial authority, which aligns with Brigantia’s role as a divine protector of Roman military power.

- “IMP” as part of the word “imperante” or “ipsius” could indicate that Brigantia herself was perceived as holding imperial authority, which ties into her depiction in the statue with imperial symbols like the Orb.

The interpretations show that scholars are still grappling with the meaning of “IMP”, and it’s evident that there’s some ambiguity in how to expand it. The fact that Brigantia is depicted with a symbol of imperial sovereignty (Orb) suggests a strong connection between her and Roman imperial power, which may or may not be directly tied to the “IMP” in the inscription. However, it’s clear that the imperial link is a key part of the interpretation and understanding of Brigantia’s role in Roman Britain.

A New Interpretive Understanding

Given the additional context of other inscriptions where Brigantia is associated with the title of Augusta, I would lean towards the interpretation that “IMP” in the Birrens inscription likely refers to “imperatum”, meaning “commanded” or “ordered,” and signifies that the dedication was made under imperial authority.

Here’s why:

Brigantia as “Augusta”

The title “Augusta”, as has been proposed to have been applied to Brigantia, and this new acceptance of the legitimacy of the IMP appellation strengthens one’s confidence that The Goddess Brigantia was also known as Augustus, as previously suggested. Acceptance of the IMP title implies that Brigantia had been elevated to a divine, imperial status within the Roman religious system. The title of Augusta was typically reserved for goddesses associated with imperial power, either as direct consorts of the emperor or as powerful deities who were closely tied to the imperial cult.

In the case of Brigantia, having the Augusta title suggests that she was seen as a high-ranking deity whose role was linked to imperial triumphs and victories. This would align with her depiction in the Birrens statue holding imperial symbols like the Orb and laurel wreath. These symbols are traditionally linked with sovereignty, military command, and victory, which reinforce her role as a protector of Roman rule and a figure of imperial authority.

“IMP” as “imperatum”

If we consider “IMP” as “imperatum” (“commanded” or “ordered”), it fits with the idea that the dedication of the statue or altar was made under imperial authority—in other words, the act of dedicating the statue to Brigantia was sanctioned or ordered by the emperor or imperial representatives. This interpretation would be consistent with Brigantia’s role as a divine figure within the imperial system, similar to other Roman deities who were either incorporated into the imperial cult or venerated as figures that legitimized Roman power.

This interpretation also seems plausible when considering the context of Romanization. As a goddess associated with victory and divine imperial rule, Brigantia would likely have been worshipped not only for local protection but also for her role in supporting the emperor. The phrase “imperatum” would reinforce her association with Roman imperial authority, and it would make sense to consider the dedication of her altar as being sanctioned by imperial command.

Imperial Symbols in the Statue

The fact that Brigantia is depicted with a Orb and laurel wreath in the Birrens statue suggests that her image and role were directly tied to imperial symbolism. These objects were used to signify Roman authority—the Orb is a symbol of sovereignty, and the laurel wreath is linked to victory and triumph. This fits well with the idea that the inscription “IMP” refers to the dedication being made with imperial sanction rather than to Brigantia herself being considered as “imperator” (commander) in a direct military sense.

Context of the Title “Augusta”:

The title of “Augusta” used in the Slack Inscription further supports this idea. It is unlikely that Brigantia, as a local Celtic goddess, was seen as an “empress” or a military commander on the same level as the Roman emperor. Rather, her imperial title would reflect her role as a divine figure in the imperial cult—a symbol of imperial power and protection. Therefore, “imperatum” in the Birrens inscription likely refers to the imperial command to dedicate the altar to her, rather than an indication of Brigantia holding the title of “imperator” herself.

How Common is it for a local deity to have IMP within their Inscription?

In Roman Britain, the abbreviation “IMP” (Imperator) is so far exclusively associated with Brigantia, as seen in the Birrens inscription.

What about IMP Inscriptions Elsewhere?

Based on the current sources and research available to me, “IMP” is not typically used in inscriptions referring to goddesses like Isis, Artemis, Cybele, or the Matronae in the same way it appears in the Birrens inscription for Brigantia. This could be an area where more research may surface additional examples, but as of now, there is no strong evidence of these other goddesses commonly being associated with “IMP” in a similar fashion.

Interestingly, no IMP inscriptions appear to have been found for any of the female deities in Rome, as far as I can ascertain. Does that increase the likelihood of it being a mistake?

Given this rarity, is this likely to have been a mistake?

Given the significance of the Birrens inscription, the importance of its location, and the fact that it was likely used regularly by many people, it seems highly unlikely that the use of “IMP” in this context was a mistake that was overlooked or ignored by the authorities.

Here are several reasons why it is more plausible that the use of “IMP” was deliberate and meaningful:

Public and Ritual Importance of Inscriptions

- Inscriptions in the Roman world, particularly those found in public places or within military contexts (like a fort in Roman Britain), were often carefully considered and crafted with attention to correct symbolism. They were used for public display, often to communicate messages about imperial power, military victories, or religious devotion.

- If an inscription was to be permanent or displayed in a prominent location, it would have been reviewed and authorized by individuals in positions of authority. Given the strategic importance of the Birrens fort, the inscription would likely have been seen by those in charge—military commanders or local Roman officials—and could have easily been corrected if there was any doubt about its accuracy.

Deliberate Syncretism and Imperial Messaging

- The Roman Empire was meticulous in its religious messaging, particularly when it came to integrating local deities like Brigantia into the imperial cult. The use of “IMP” (Imperator) alongside Brigantia could have been a deliberate effort to elevate her from a local deity to a divine protector of Roman power—very much in line with the Roman strategy of assimilating local deities into the imperial structure.

- Given Brigantia’s evident association with military victory and Roman sovereignty, especially through her depiction with imperial symbols like the sceptre and laurel wreath, it’s very likely that the use of “IMP” was a strategic decision to link her with imperial authority. It would make sense that Roman officials would be aware of this choice and would approve of it as part of the Romanization process in Britain.

No Evidence of Correction or Objection

- In Roman times, inaccuracies in inscriptions, particularly those associated with imperial titles, were not easily ignored. The Roman military and administrative structures were incredibly organized, and any errors, especially those concerning titles like Imperator (which had specific connotations regarding the emperor’s authority), would typically have been corrected quickly.

- Moreover, there are no records or evidence of anyone in the Roman military or political structure objecting to or correcting the inscription. If it had been a mistake, especially one involving the “IMP” title, it would likely have been addressed by the local authorities—either by rewriting the inscription or by issuing a correction elsewhere.

The Role of Brigantia in Roman Britain

- Brigantia was clearly an important figure in Roman Britain, and her role as a goddess associated with victory and protection of the empire would have been well understood by both the military and local populace. Given her prominent position within the Roman religious framework in Britain, her association with imperial power would have been purposeful and intended to communicate the connection between local and imperial power.

- The imperial symbol on her altar, which connects her to the emperor’s power, would not have been a mistake. Instead, it reflects the growing integration of local deities into the Roman system, particularly in the provinces.

Symbolism and Long-Term Impact

- The inscription will displayed publicly and was not just for one-time or private use. It was intended to affirm the presence of Roman authority and legitimize the emperor’s power within the local religious context. Any mistake or inconsistency in such an inscription would likely have been noticed quickly by the public, especially if it affected the perception of imperial power.

- Therefore, the use of “IMP” in this context, particularly in association with Brigantia as a figure of imperial power, would have been carefully managed and seen as a calculated act.

Unlikely to Be a Mistake

The chances that the use of “IMP” in the Birrens inscription was a mistake that was overlooked or ignored by everyone in power are extremely low. Given the strategic importance of the inscription, the role of Brigantia as a protector of Roman power, and the highly organized nature of Roman military and administrative practices, it seems much more likely that the use of “IMP” was a deliberate decision meant to highlight Brigantia’s elevated status as part of the Roman imperial system.

Rather than being an error, it was likely an intentional choice to position Brigantia as a divine protector of imperial rule, symbolizing her authority and connection to Roman power in Britain.

Other Female Deities with Orbs

There are instances in Roman art and imperial iconography where female deities are depicted holding an orb or objects with orb-like symbolism. These examples reflect the importance of the orb as a symbol of sovereignty, cosmic order, and imperial authority, which were sometimes attributed to female deities, particularly those associated with victory, protection, and cosmic order. However, it’s important to note that while the orb was more frequently depicted with male rulers or gods, female deities also appeared with the orb in specific symbolic contexts.

Minerva

- Minerva, the Roman goddess of wisdom, warfare, and crafts, is sometimes depicted holding the orb in representations that emphasize her role in defending or protecting the cosmic order. As a deity closely linked to the emperor and the imperial cult, she could be shown holding the orb as a symbol of her sovereignty over wisdom and her divine role in maintaining cosmic harmony.

- In some Roman coins and sculptures, Minerva is shown holding both the spear and the orb, signalling her military and intellectual authority, as well as her divine protection of Rome and the empire.

Victoria

- While Victoria is more commonly shown with symbols of victory (such as a palm branch or wreath), there are instances where she is depicted holding an orb. These depictions symbolize her role as a goddess of imperial victory and cosmic power, often in conjunction with her association with the emperor’s triumphs.

- The orb in Victoria’s hand can represent her role in the emperor’s divine legitimacy—just as the emperor holds an orb to signify his rule over the empire, so too does Victoria hold it as a symbol of imperial success.

Cybele (Mater Deum)

- Cybele, the Great Mother goddess, was a deity widely worshipped in the Roman Empire, especially in the eastern provinces. She was often depicted holding the orb as a symbol of her cosmic power and authority. As a mother goddess associated with both fertility and protection, Cybele’s connection to the orb emphasized her role in maintaining cosmic order and providing sovereignty over the world.

- The orb also symbolized her role as a protector of the Roman state, and the orb in her iconography could serve as a representation of her protection of the imperial order, particularly during times of military expansion and conquest.

Roma

- Roma, the personification of the city of Rome, was often depicted as a powerful female deity holding the orb. In some of her depictions, Roma is shown as a warrior goddess, holding both a spear and an orb. The orb, in this case, represents Rome’s dominion over the known world—her rule over the empire.

- The orb in Roma’s depictions symbolizes not only the sovereignty of the city of Rome but also its role as the centre of imperial power and as the foundation of the Roman Empire’s cosmic authority.

Ceres

- Ceres, the goddess of agriculture and fertility, is sometimes depicted with an orb in later Roman depictions. While she is more commonly shown with wheat or cornucopia, the orb in some depictions emphasizes her role in the abundance and control over the earth and the cyclical nature of agriculture, symbolizing her sovereignty over the natural world.

- The orb here may also carry a cosmic or divine governance symbolism, suggesting her control over the earth’s fertility and the cosmic forces that govern it.

Summary: Female Deities and the Orb

- Minerva: The orb in Minerva’s depictions emphasizes her role in protecting cosmic order and possibly her connection to imperial authority.

- Victoria: While more commonly associated with victory symbols, she occasionally holds the orb as a representation of her role in imperial success.

- Cybele: The orb symbolizes her cosmic power and her role as a protector of imperial rule.

- Roma: The orb in Roma’s depictions represents her dominion over the empire and imperial sovereignty.

- Ceres: The orb in Ceres’ depictions suggests divine control over the natural world and cosmic order.

In these examples, female deities holding the orb are often associated with cosmic authority or imperial power, though it is more typical for male rulers or gods to be depicted with the orb. However, as the deities themselves often represented forces that governed imperial sovereignty (like victory, fertility, cosmic order, and protection), it is not surprising that female deities were depicted holding the orb in representations of their divine rule and guardianship over these powers.

Analysis of the Orb Position

The hand with which deities hold the orb can carry subtle symbolic significance, especially in the context of Roman iconography, where the position and symbolism of each object were carefully considered.

Analysing of Which Hand the Orb is Held With

Minerva:

- Positioning: Minerva is often depicted holding the orb in her left hand, while her right hand typically holds a spear or olive branch.

- Interpretation: The left hand holding the orb could symbolize the cosmic and intellectual domain over which Minerva rules, as the left hand was often associated with the passive, receptive side, representing wisdom, reason, and divine protection. The right hand, which is more often shown in active poses (such as holding the spear), might symbolize the military and active role of the goddess. This positioning reflects Minerva’s dual nature as both a goddess of wisdom and warfare.

Victoria:

- Positioning: Victoria is generally depicted holding the orb in her left hand, with her right hand either raised in a gesture of blessing or holding a palm branch, both symbols of victory.

- Interpretation: Like Minerva, the orb in the left hand of Victoria may emphasize her role as a cosmic or divine protector of victory, while the right hand (usually in the gesture of triumph) reinforces the active victory and empirical achievement associated with imperial triumphs. This positioning associates the right hand with action, while the left hand symbolizes cosmic order and victory’s divine backing.

Cybele:

- Positioning: Cybele is often depicted holding the orb in her right hand, with her left hand sometimes resting on a lion or a throne, or in some cases, holding a cornucopia.

- Interpretation: Holding the orb in the right hand may signify active rule, power, and sovereignty. As Cybele is the goddess of the earth and fertility, her right hand holding the orb indicates dominion over nature and the empire’s protection, tying her to imperial authority and the cosmic balance she represents.

Roma:

- Positioning: Roma is depicted holding the orb in her left hand, while her right hand often holds a spear or is in a gesture of salutation.

- Interpretation: Like Victoria, Roma’s holding the orb in her left hand may reflect her cosmic sovereignty over the empire, while her right hand, associated with action (holding a spear or making a salutation), symbolizes Roman military power and the active defence of the empire. The orb represents her worldly and cosmic power as the embodiment of the Roman state.

Ceres:

- Positioning: Ceres is sometimes depicted holding the orb in her left hand, with her right hand holding a sheaf of wheat or a cornucopia.

- Interpretation: The orb in Ceres’s left hand aligns with her dominion over the earth and natural order, while the right hand, which holds symbols of fertility and nourishment, emphasizes her active role in life-giving and agricultural abundance. The orb might symbolize her cosmic connection to the fertility of the earth.

General Symbolism Behind the Left and Right Hands

-

Left Hand (Passive): In Roman iconography, the left hand is often used to symbolize the receptive, passive side of a deity, representing cosmic order, divine protection, and sovereignty over the universe. Holding the orb in the left hand suggests a cosmic or divine authority that is above the physical or military realm. It may also reflect the idea of cosmic dominion, where the goddess is viewed as a higher power who presides over the earthly realm.

-

Right Hand (Active): The right hand, conversely, is typically associated with action, authority, and active power. It is often depicted in gestures that involve military leadership, triumph, or domination. For goddesses like Victoria or Roma, who are associated with military or imperial success, the right hand holding a spear or palm branch reinforces their role as active participants in the military or imperial triumph.

We can therefore conclude the following:

- The Left Hand: For most female deities associated with imperial power (such as Minerva, Victoria, Roma, and Ceres), the orb is typically held in the left hand, symbolizing their role in the cosmic and sovereign domain, over which they rule.

- The Right Hand: The right hand often holds symbols that represent action, such as a spear or wreath, and signifies the deity’s role in military leadership, victory, and imperial sovereignty.

This careful positioning highlights the dual nature of these goddesses: they combine cosmic authority with active rule, protection, and imperial power. The orb in the left hand represents their divine legitimacy, while the right hand emphasizes their role in earthly governance and the protection of Roman imperial order.

Suggested Revised Translation

The inscription is dedicated to Brigantia, of the divine Emperors, and it focuses on the dedication of the statue. It should be interpreted as:

“To the goddess Brigantia, of the divine Emperors. Lucius Celer, Centurion, fulfilled his vow. Well-deserved.”

Breakdown of the Revised Interpretation

“Brig(antiae Deae)”

- This simply means “To the goddess Brigantia.”

- It confirms that Brigantia is the central figure of the dedication and that the offering is made to her.

“Imp(eratoribus Divis)”

- This refers to the “divine Emperors”. In Roman religious practice, this would typically indicate the deified emperors who were considered divine figures.

- This doesn’t mean Brigantia is being deified alongside the emperors, but rather she is linked to them in her role as a protector of imperial authority and as part of the Romanized religious system. The wording connects her to the imperial cult and suggests that she shares in the divine protection of the empire, much like the emperors themselves.

“Votum Solvit”

- This means “fulfilled his vow,” indicating that the centurion, Lucius Celer, has completed a vow (likely a religious or military vow), which typically involved dedicating an offering or statue to a deity in return for divine favor or protection. In this case, the vow is fulfilled in the form of a dedicated statue of Brigantia.

“L(ucius) Celer, Centurio”

- This names the centurion (Lucius Celer) and his rank, emphasizing the military context of the dedication. This shows that the offering and dedication of the statue were directly related to the military and Roman soldiers’ religious practices, where they would offer votive dedications to the gods for their success and protection.

“Bene Merito”

This means “well-deserved,” affirming that the vow has been fulfilled properly, and likely that Brigantia, as a protector goddess, has provided the requested favour or protection.

Summary of the revised Interpretation

This inscription commemorates the dedication of a statue to Brigantia, associating her with the divine emperors—i.e., she is linked with the imperial cult and the imperial protection of the Roman Empire. The centurion Lucius Celer fulfilled a military vow by dedicating the statue, reinforcing Brigantia’s role as a protector of the Roman army and imperial authority.

I believe that the interpretation I’ve suggested is much more accurate in capturing the essence of the inscription. It highlights Brigantia’s status as a high-ranking Roman goddess, which, within Brigantia, we can now see clearer that there is indeed evidence to show this aspect of the inscription was never a mistake.

Conclusion: Brigantia’s Significance reinforced

Based on the various pieces of evidence we have explored, here’s a summary of the my proposal that an alternative interpretation of this important inscription holds a much stronger case for support that the current interpretation. The case for this can be summarised as follows:

- Iconography: Brigantia’s depiction with imperial symbols like the sceptre and laurel wreath aligns her with high-ranking Roman deities.

- Inscriptions: The use of “IMP” and “Augusta” in her inscriptions places Brigantia within the context of the imperial cult, suggesting that her role had been elevated to one of imperial significance.

- Syncretism: The blending of Brigantia with multiple Roman deities, such as Victoria, Minerva, and Roma, indicates her transformation into a goddess who not only represented local Celtic identity but also Roman imperial power and divine authority.

- The Orb: Her possible association with the orb reinforces the idea that Brigantia was positioned as a cosmic protector, similar to other top-tier deities like Juno or Minerva.

Confession time 🙂

You may have noticed, that whilst I stated that I wanted to build as strong a case as possible, that there is a lot of detail on the statue that I did not mention. Well, truth be told, I wanted to show you how much evidence there was. And how, actually, I was able to build a strong case by only looking at some of the evidence. It also made sense to try to about excessive verbiage caused by the need to include elements which, in the end were not need to in order to create a more safe interpretation of the evidence available.

But, now we have done all that, why not take a look at all the major features of the statue? Here is the official description:

“In high relief standing in a gabled niche. The goddess Brigantia is winged, has a Gorgon’s head on her breast, and wears a plumed helmet encircled by a turreted crown. In her right hand she holds a spear, in her left a globe; to her left stands her shield, to her right an omphaloid stone.”

ChatGPT said:

This detailed iconography significantly enhances our understanding of Brigantia’s elevated role in the Roman period, especially in relation to imperial power. Let’s break down the important elements of this statue and what they suggest about Brigantia IMP:

Winged Brigantia

Symbolism: The wings on Brigantia are a powerful symbol of divine power and speed, often indicating that the goddess is a figure who transcends earthly limitations. Wings are typically associated with deities of victory or those who represent military power (e.g., Victoria, the Roman goddess of victory, is often depicted with wings). In this case, the wings elevate Brigantia to the status of a divine protector, linking her to the imperial military and representing her role in ensuring the success of the Roman army.

Connection to Imperial Power: The wings also suggest that Brigantia is a transcendent and cosmic figure—one who is not only a protector of the local people but also a goddess associated with the entire empire, with the ability to oversee the Roman empire’s divine order.

The Gorgon’s Head on Her Breast

Symbolism: The Gorgon’s head (often associated with Medusa) is an ancient symbol of protection and warding off evil. It signifies power over adversaries and enemies. The Gorgon was frequently used in Roman iconography to symbolize divine protection against harm or military defeat.

Connection to Brigantia: The Gorgon’s head on Brigantia’s breast signifies that she has a role in protecting the empire—particularly through military victory. The presence of the Gorgon emphasizes her role as a protectress of the empire, particularly in its military endeavours.

The Plumed Helmet and Turreted Crown

Symbolism: The helmet and turreted crown reinforce Brigantia’s association with military power and sovereignty. The plumed helmet is a symbol of warrior status and military command. The turreted crown (a crown with turrets or fortifications) is a symbol of defence and fortress-like power. It often represents the protection of a city or empire, and the goddess’s dominion over it.

Connection to Brigantia: These elements signal that Brigantia is not just a local protector but is imperial in scope—a figure of defensive power who could be trusted to safeguard the Roman Empire and its military conquests. The turreted crown places her on a level comparable to Roman deities like Minerva or Victoria, both of whom were strongly connected to military success and protection.

The Spear in Her Right Hand

Symbolism: The spear is a classic symbol of military authority and victory. It directly associates Brigantia with military prowess, and its presence suggests that she is a goddess of military success. In Roman iconography, the spear often signifies active military power and defensive strength.

Connection to Brigantia: Holding the spear in her right hand, Brigantia embodies active power and control over military affairs. This reinforces her status as a warrior goddess and a military protector of the Roman empire.

The Globe in Her Left Hand

Symbolism: The globe represents sovereignty over the world and imperial dominion. In Roman iconography, the globe is often held by figures who symbolize cosmic rule or universal power. The left hand holding the globe may signify passive dominion or cosmic authority over the world, in contrast to the active military power of the spear in her right hand.

Connection to Brigantia: The globe in Brigantia’s left hand signifies that she not only holds earthly dominion (via her military protection) but also represents cosmic order and universal sovereignty. This elevates her to the rank of a cosmic protector, one who governs over the entire world, aligning her with the highest deities in the Roman pantheon, such as Juno or Minerva.

The Shield to Her Left

Symbolism: The shield represents defence and protection—it is a symbol of defensive strength, often associated with warrior deities and military leaders. In many depictions of Roman deities, the shield is used to signify their role as protectors of the empire and its people.

Connection to Brigantia: The shield suggests Brigantia’s defensive role, both as a protector of Roman soldiers and as a goddess of the empire’s security. This reinforces the idea that Brigantia is integrally connected to the defence of Roman power and military success, serving as a shielding force against both external and internal threats.

The Omphaloid Stone to Her Right

Symbolism: The omphaloid stone (often described as a navel-shaped stone) is an ancient symbol of the centre of the world, representing a point of divine origin or cosmic significance. It was often used to symbolize a link to the divine and the spiritual centre of the universe. The stone suggests a connection to the earth or the foundations of power.

Connection to Brigantia: The stone’s placement to Brigantia’s right emphasizes her role as a foundational figure—one who represents not just military defence but also divine authority rooted in the cosmic order. It connects her to the core of Roman power, suggesting she is at the centre of the empire’s spiritual and military strength.

Conclusion: The Elevated Status of Brigantia

The detailed description of Brigantia in high relief standing in a gabled niche conveys her elevated status in the Roman world, aligning her with some of the highest deities in the Roman pantheon. The combination of imperial symbols—the winged figure, Gorgon’s head, plumed helmet, turreted crown, spear, globe, shield, and omphaloid stone—places her at the centre of imperial power.

This depiction of Brigantia IMP is not only a goddess of victory and military protection, but also a cosmic ruler, embodying both earthly military dominion and universal sovereignty. She is equivalent to high-ranking deities like Victoria, Minerva, and even Juno in her role as a divine protector and emissary of imperial power. The imperial symbolism clearly positions Brigantia as a key figure within the Romanized religious system, possibly one of the highest-ranking deities in the Roman world.

Exploring Alternative Sources

To get a fuller view of the debate and symbology surrounding the Birrens statue and its inscription, you might find some alternative sources that directly address the iconography and visual culture of Roman Britain. These sources are likely to explore not only the inscription but also how local deities like Brigantia were represented visually, and how their iconography reflected Romanization. Here are a few suggestions:

- “Roman Britain: A New History” by Guy de la Bédoyère – This book provides a broader context of Roman Britain, exploring how Roman symbolism was applied to local deities, often using statues and artifacts to illustrate the fusion of Celtic and Roman culture. It might offer insight into how statues like Brigantia’s were reinterpreted to fit the imperial context.

- “The Art of Roman Britain” by Michael H. C. H. Williams – This source provides a more focused discussion on Roman art and iconography, including the use of imperial symbols in depictions of local gods. It might help explain how Brigantia’s Orb and laurel wreath fit within broader Roman visual traditions.

- “Roman Britain and the Roman Empire” by Peter Salway – This book discusses Roman Britain in both historical and cultural contexts, including the integration of local deities like Brigantia into Roman religious practices. Salway could provide an easier-to-understand framework for interpreting Brigantia’s iconography.

- “The Imperial Cult and the Roman Gods” by John Scheid – This work delves into how Roman deities were depicted with imperial symbols like the Orb, laurel wreath, and spear, and how these symbols reflected the imperial cult. The comparison with Brigantia would likely help bridge the gap between her local Celtic roots and her Romanized role.

-

-

Clann Bhríde Additionally, the article “The Exalted Ones” provides insights into the syncretic nature of Brigantia’s depiction, highlighting her association with Roman symbols and deities.