“Celtic” carved heads are found throughout the areas of Europe once dominated by those peoples Caesar called Celts, in the area dominated by the Iron Age Brigantes tribe (United Kingdom) more than 2000 carved heads have been identified which are thought to be of ancient origin, although the portability of many head carvings means that dating is almost impossible and it is also safe to assume that the carving of heads was not limited to the Iron Age period but was a ritual/religious form of expression which continued from at least the Iron Age to modern times, the practice continuing, though almost certainly the reasons and motives behind the act will have changed.

Some Celtic heads certainly have a provable ancient origin, and their location establishes a close relationship between religious practice and the carving of of heads.

St Michaels Church, Brough in Westmorland has a good example of a head carving with potential ancient origins. This head was built into the lower stage of the Norman tower of the Church, no doubt rebuilt several times over the years however the head is certainly out of character for the design of the modern church, and given the church was built over the site of a Roman temple or shrine within a Roman fort it is safe to assume that this location was a centre of religious devotion for at least 2000 years. The Romans tended to build their temples over or alongside the temples of the indiginous peoples so it is a reasonably safe assumption that this site was a Celtic place of ritual and that this carving was inspired by local Iron Age beliefs if not actually of Iron Age origin.

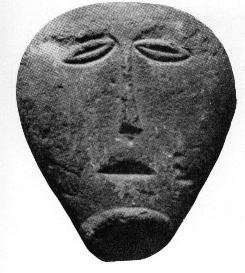

Carved head from St. Michaels Church, Brough.

Relief of Celtic God from Roman York, The head of the god has large eyes, a drooping moustache and hair which flairs from the face.

Head from Bradwell Church, Derbyshire. This ghostly head come from a region where the last of the “original” British Celts claim to survive.

Head from Hope Church in Derbyshire It is difficult to say the date for this head, although again it is built into the lowest section of the Norman tower, so certainly has ancient origins. Hope church is dominated by heads of later origins and surely was a centre for the continuity of the head “cult”.

Head on sale in an antique shop in Hawes for £140.00. Heads such as these have no provenance and whilst this one exhibits many features that would indicate that it is a “Celtic Head” it’s lack of provenance would make one hesitate to purchase it. Stone can be sculpted and made to look old quite easily.

Heads from All Saints church, Birchover.

Heads from Egglestone Abbey, Durham. These heads, like many others are undoubtedly later, but were they inspired by the local tradition?

This Head from the church at High Bradfield, Derbyshire has a moustache and may also have been of Celtic inspiration.

Pagan gargoyle from the church at Hope, Derbyshire, a mixing of Celtic heads with water?

Celtic head intalled under a water gully in a modern bridge in Derbyshire. Continuation of a Celtic fascination?

Celtic Heads and Water

The evidence of ritual deposits in watery locations has shown that throughout the Iron Age and before, man attached a ritual significance with water, it is highly probable that the Celts believed many of there gods existed in water and could be comunicated with by the placing of a ritual sacrifice.

There is some evidence, of both modern and ancient origin to suggest that there was also a significance to the placing of heads in the proximity of water.

Often it appears that a head should be placed so water should flow over it, which is possibly the inspiration for later gargoyles so common throughout Europe.

Guy Ragland-Phillips identified this association in his book – Brigantia:

“Giggleswick, near Settle, has a number of wells which not long ago were regarded as healing. … Giggleswick Church stands in the middle of the group of wells. Inside the church, as a corbel to an arch, is a carved stone Celtic head far older than the church itself. Built into the wall on the outside is another, probably about 1,700 years old or more. The church’s dedication of “St Alkeld” is the Saxon for “Holy Well”.”

“Over the hill in Kirkby Malham, the church has two well known Celtic stone heads built into one wall in the nave. There is a third in the porch this is reminiscent of a crude stone carving found at Carraburgh. Two hundred yards away up the dell is a “spa well” reputed to be sulphorous and healing.”

“The St. Helens wells between Skipton and Bolton Priory are rarely visited. The one on the lower wharfe, just beside a ford which the Romans used, is now abandoned on the edge of a sewage farm. Only the one at Eshton still seems safe….Bend double beside the pool, and feel the big stones that stand just under the water at the junctions of the kerbstones, and you will find that they are carved stone heads.”

Head from Bedale church, North Yorkshire. This head is found in the interior of the church, and is in particularly good condition.

Horned Head from Well, North Yorkshire. Horned heads are also a common feature of the Celtic heads that are found. This is part of a cluster, others occuring in Catterick, Aldborough (both in Roman Context) and Kirklington.

“[The Gauls] cut off the heads of enemies slain in battle and attach them to the necks of their horses. The blood stained spoils they hand over to their attendants and carry off as booty, while striking up a paean and singing a song of victory, and they nail up these first fruits upon their houses just as those who lay low wild animals in certain kinds of hunting. They embalm in cedar oil the heads of the most distinguished enemies and preserve them carefully in a chest, and display them with pride to strangers, saying that, for this head, one of their ancestors, or his father, or the man himself, refused a large sum of money. They say that some of them boast that they refused the weight of the head in gold…” Diodorus Siculus.

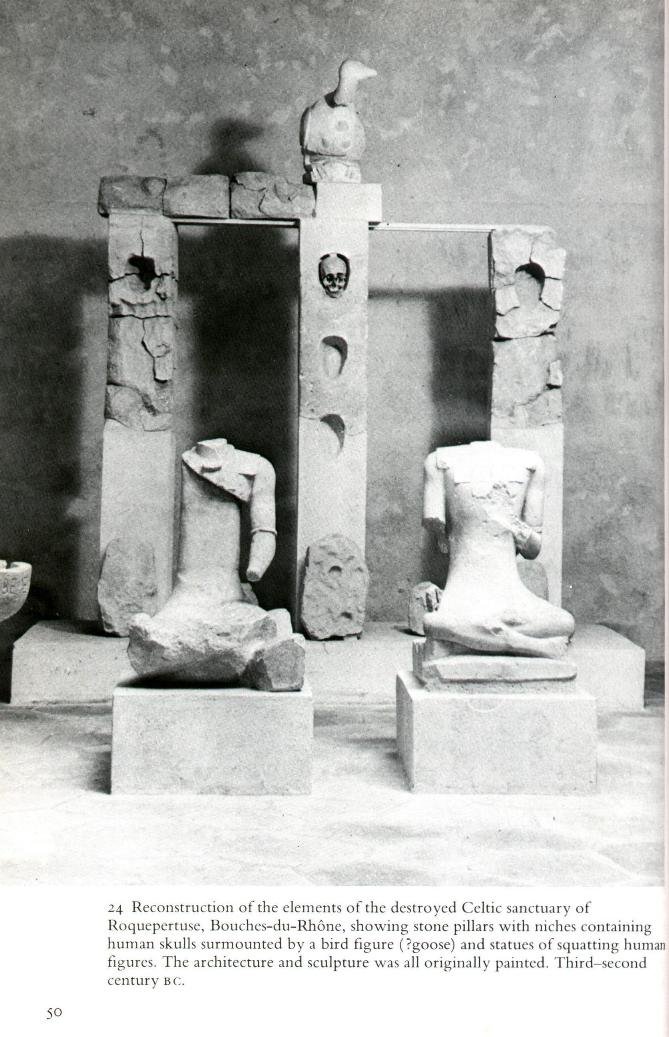

This carved stone pillar dating to the second century BC shows that head carving was certainly a feature of Iron Age western Europe.

The “Blackamoors Head” from Rivington, submitted by Martin Davies has a drooping mustache typical of some Celtic heads, however, it’s general makeup would indicate a date of possible Medieval origin.

“There is also that custom, barbarous and exotic, which attends most of the northern tribes…when they depart from the battle they hang the heads of their enemies from the necks or their horses, and when they have brought them home, nail the spectacle to the entrance of their houses. At any rate Posidonius says that himself saw this spectacle in many places, and that, although he first loathed it, afterwards through his familiarity with it, he could bear it calmly.” Strabo IV, 4,5. Speaking of the Gauls.

Horned Head from Carvoran, Northumberland. 3rd Century AD.

“What strikes me as above all significant is not so much whether this head or that is genuinely Celtic or not, but the extraordinary continuity of culture shown by this collection, Presumably without knowing it, there are local craftsmen of this very century in these Yorkshire industrial valleys, carving heads with specific characteristics such as the “Celtic eye”. I had always imagined the West Riding to be an industrial hotchpotch in which all traces of past cultures would have been obliterated. I had failed to realise that each mill-town and village was, almost to this day, largely cut off from the others and isolated. It is a treasure house of continuity” Anne Ross, speaking about Sidney Jacksons collection of “Celtic” heads from West Yorkshire

Head from Castleton, South Yorkshire (Sheffield Museum).

One of Sidney Jackson’s Celtic heads.