What was so special about The Sacred Vale and Thornborough in particular, that meant this enormous monument complex had to be created? This is in no way a typical landscape for the time – nowhere else in Britain does a complex exist such as it does in The Sacred Vale. It was chosen to be transformed into a sacred landscape – a place of great importance. The landscape created here was unique, it required tremendous effort on an unprecedented scale, it was not at all like the same period landscapes elsewhere. It shone like a beacon in later Neolithic religion. Surely, there was some reason for this beyond purely a religious motivation – why here and not elsewhere?

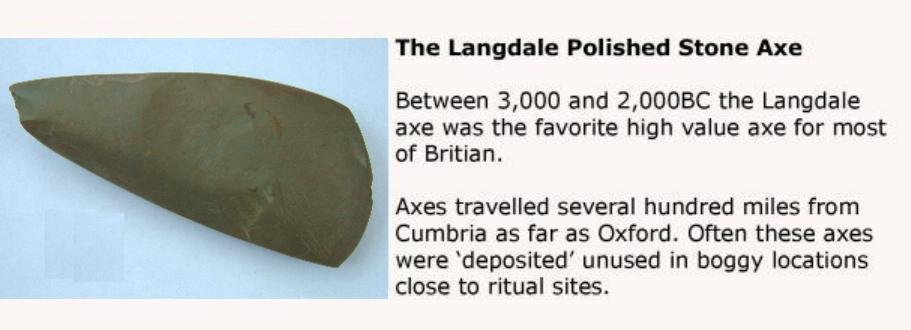

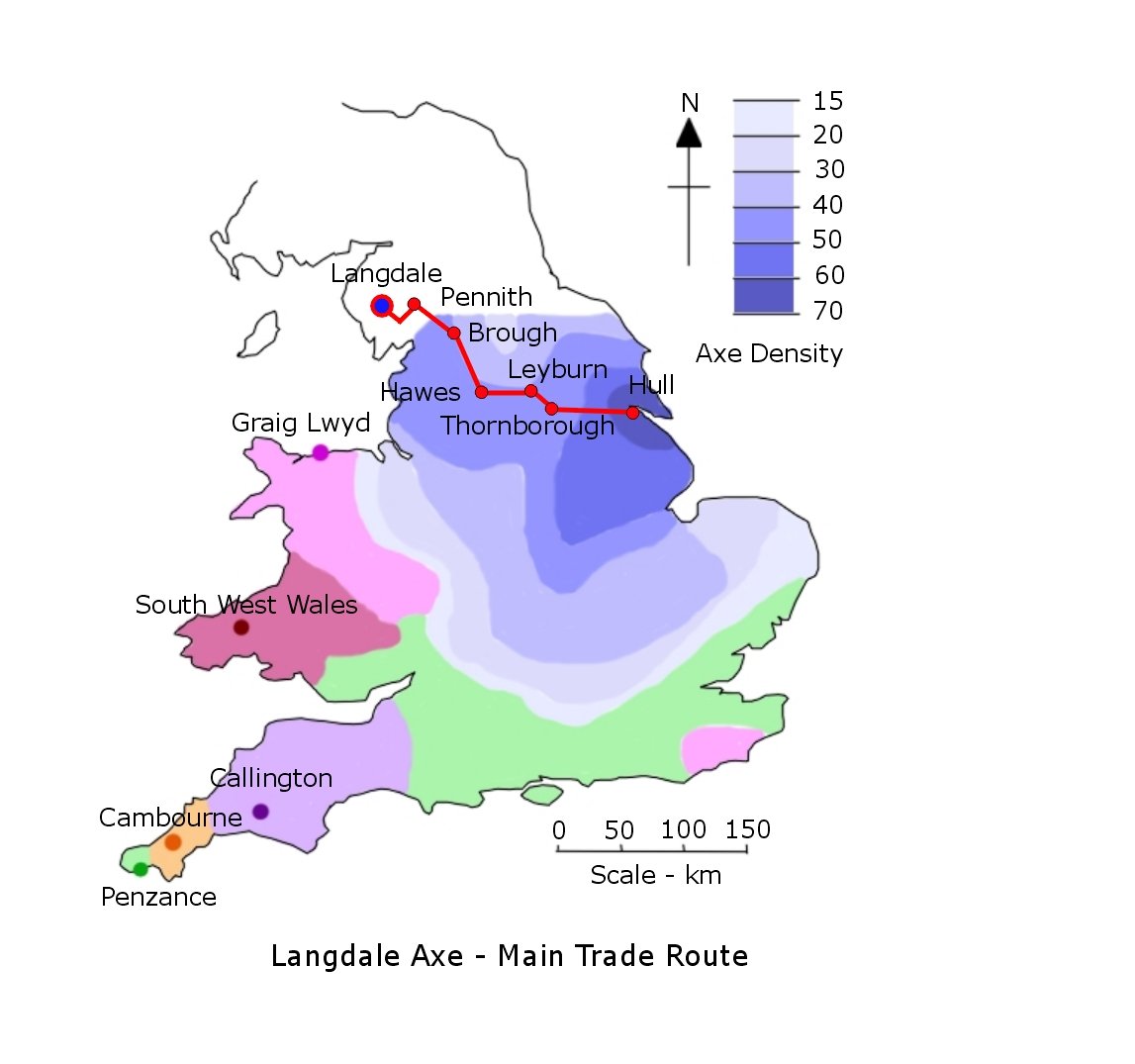

Image: Langdale Stone Axe Distribution. After Cummins.

Image: Flint Axe, Joanne.

The first thing to note is that Thornborough is on a line alongside the impressive river Ure. The religious connotations that the major rivers of the area such as the Ure would have had in the period have already been mentioned. Rivers were particularly important during the Late Neolithic period; this is because during this time across Britain, rivers were route-ways for exchange.

During the time of the growth of Henge building across Britain there was also a significant expansion in the trading of polished stone axes – a number of which have been found in the landscape around Thornborough.

In the Later Neolithic period there developed a remarkably widespread trade in polished stone axes. For some reason, axes from a few particular production centres were travelling very large distances and had obviously acquired a value well beyond the simple material value that an axe would have had in the period.

The diagram showing the distribution of the Langdale Axes illustrates this point. If these axes were for purely utilitarian purposes, the distribution pattern would centre on the place of origin – more would be found closer to the production centre than in those areas further away – as the distance to the axe source increased people, would be more likely to find alternative sources of axe material.

Yet for all polished stone axes, not just Langdale, the opposite is the case – more axes are found as one travels away from the production site. With Langdale Axes, the production sites are found in the Lake District in Cumbria, yet the largest concentrations of axes have been found in East Yorkshire.

Perhaps for the first time in Britain, items that would have been a commodity appear to have transcended the low value of local utility, becoming objects of national desirability.

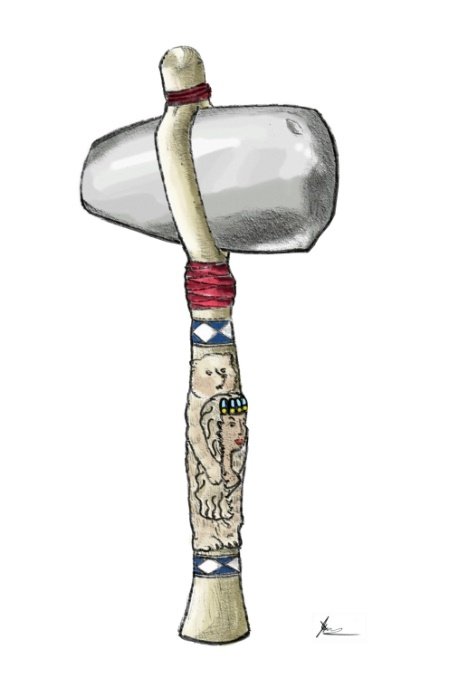

Image: Stone Axes – analysis of the dominant types.

Axes began travelling hundreds of miles from their source, some even crossing the North Sea into Europe. This growth in long-distance trade, and the unrealistic value that was apparently attached to them, is a phenomenon that appears to coincide with the massive growth in henge building.

Image: Scottish Flint Axe from Thornborough.

The evidence presented by the distribution of the Langdale axes tells an important story. It is almost as if they were a prestige-branded good – for Neolithic people they were objects of desire that demanded a high price; they were “must have” items that travelled hundreds of miles and were made in large quantities.

The Langdale Axe is distributed in the highest quantities and over the greatest geographic area of any axe for the period – “outselling” the rivals by over 250%, if the number so far found is to be taken as representative. Comparatively speaking, the Langdale Axe trade was a very significant economic exercise that was important countrywide.

What is of most interest is the role these axes appear to have played in the ritual life of the Late Neolithic people. Archaeologists have concluded that they were of prestigious importance and were high status objects.

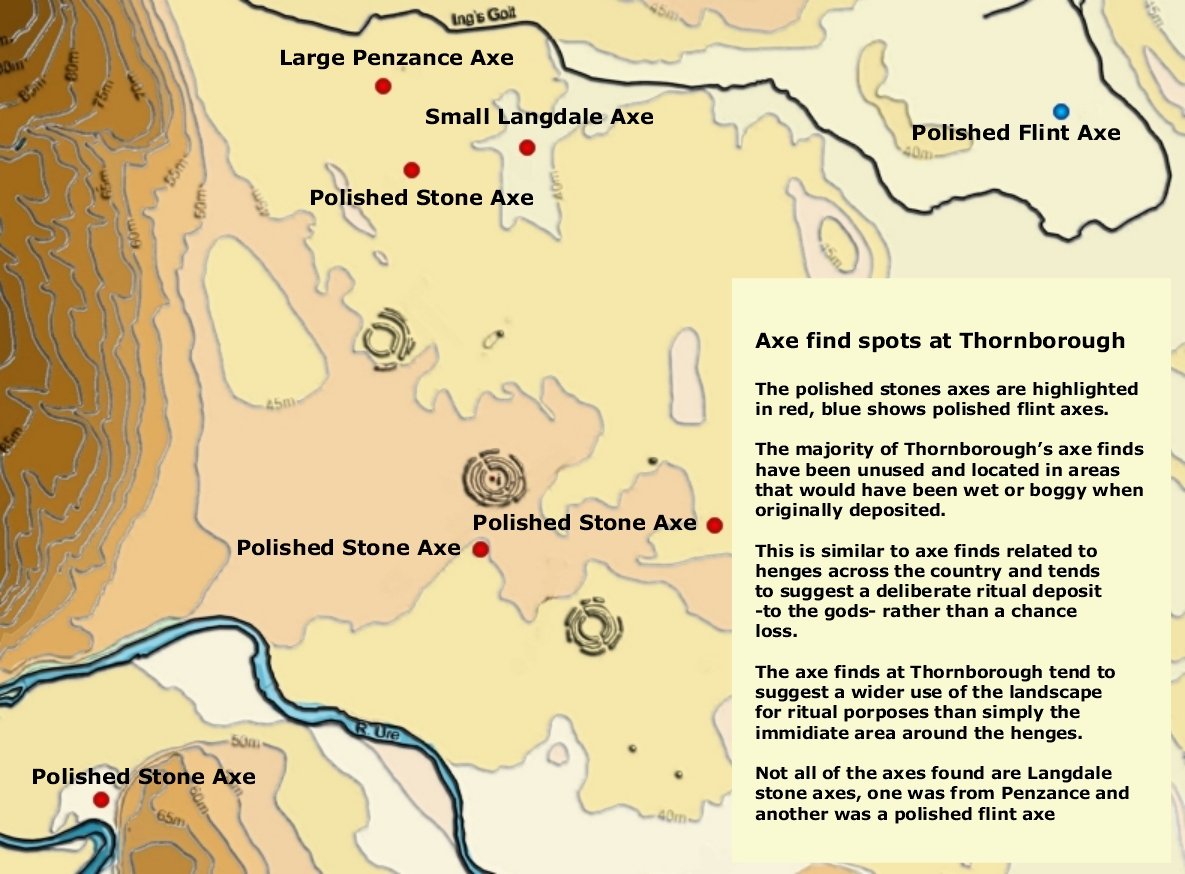

Rather than being used as axes, it would appear that a great many of these polished stone axes were used as ceremonial items. Many have been found in an unused state either deposited as offerings in ritual deposits, typically in a watery context, or included in the grave goods of high status individuals.

They were symbols of leadership and could well have been regarded as the most worthy objects of ritual donation. At least three of the axes found at Thornborough were deposited in water – an act that is recognised as an offering to the gods.

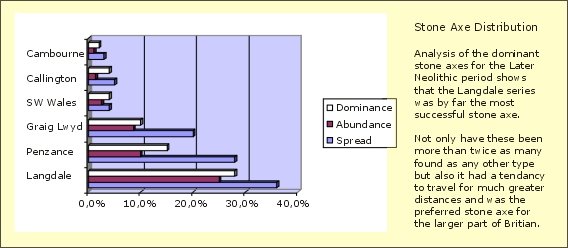

Image: Langdale Axe from Heslerton.

Archaeologists have called the Langdale Axe the “Ferrari of the Neolithic Age” as a way of communicating their value during the period – an object whose value was almost incalculable. Any locations that sat on a major trade route for such goods would have seen a massive increase in the value of goods and the number of people passing through.

This is very significant for Thornborough because of the river Ure. It would appear that the river Ure was a major trade route during the Later Neolithic period, creating part of a major route-way from the east of England to the west. This included the route to the Lake District and the Langdale axe factories.

Where the Ure runs out at the head of Wensleydale, it is a short trip to the River Eden that flows to the west towards the Langdale axe working sites, the source of the most widespread type of ritual axe in Britain.

The distribution of the Langdale axe serves to highlight a significant relationship between this axe trade and the Sacred Vale. Most Langdale axes have not been found at Langdale, or even Cumbria. They have the most widespread distribution of any Early Neolithic axes and, significantly, a very high proportion of Langdale axes have been found on the east coast of Britain around the Humber estuary. The River Ure ultimately terminates here, having changed its name to the River Ouse after it leaves the Sacred Vale.

This growth in trade and the value of the trade goods turned the River Ure into the equivalent of a motorway, a premier trade route that brought people, objects, ideas, relations and rituals flowing in either direction and passing through Thornborough.

In exchange for those axes, it is likely that other goods were moving westwards into Cumbria. This was a beneficial system of exchange that spanned the width of Northern England. Thornborough is likely to have been one of the hubs of this exchange route.

Image: Postulated axe route to the Humber.

Whilst much of this section has been written with an economic slant, it should be noted that it is highly unlikely that the people of the era recognised the same values as we do today, and it has been suggested that, like many modern tribal societies’ trade may also have included the acquisition of marriage partners, tribal alliances and information.

It should not be forgotten that modern people often impose their own concepts and values on the perceived behaviour patterns of our ancient forebears. The distribution of stone axes is widely accepted as the outcome of trade; however, other social drivers unknown to us may have been in place. For example, whilst there are many locations in Britain that could easily provide good sources of axe material, all the Neolithic polished axe sources are in particularly difficult to access locations. These sites may have been chosen for their own ritual significance and that the act of travelling to the site, making an axe and delivering it to a particular destination, was a specific ritual in itself. Perhaps the act of procuring the axe itself was an epic and heroic task, required before an individual would be accepted as a leader.

Axes at Thornborough

Image: Devil’s Arrows crop circle. 2003. www.northerncircular.org

To refocus on the Sacred Vale, and the six identical Henges in the alignment, it can be seen that the alignment serves to create a very significant ritual landscape along this river valley. The monuments form an alignment of identical henges along two straight lines – one approximating to the Ure, the other to the Swale. Both lines meet at Boroughbridge, home of the Devil’s Arrows stone alignment and also very close to the confluence of the two rivers. The Vale of Mowbray was well-placed to attract people; this was a major thoroughfare, an important route-way. People were coming and going through this landscape. This is important from an archaeological sense because it ties in with the evidence from the field walking.

During the Later Neolithic, the vast majority of people who visited Thornborough did not live here all year round. Rather they were visiting Thornborough – the flint that is found has very slight amounts of use that suggests that it was not used for long periods. This helps confirm the suggestions made in regard to the short-stay camps.

A piece of evidence relating to trade also comes from the flint. Of that found, among those implements made from local flint were a high proportion of objects made from east coast flint. There is also flint from the Yorkshire Wolds and churt from the Pennines. This helps confirm that people were travelling large distances to get to Thornborough.

To add to this, Langdale Axes have been found at Thornborough, and the most travelled axe found here, in a ritual deposit context, came from Penzance – a journey of more than 500 miles.

It was not just local people coming to Thornborough, but people who had come from very different landscapes. It is likely that they were travelling to Thornborough at set times of the year, and some were apparently coming to deposit offerings.

All this is very reminiscent when put in one context – pilgrimage. Pilgrimage is a global phenomenon even today; it’s been an aspect of worldwide religious expression for at least a thousand years. In the medieval years people undertook pilgrimages, this is the reason for the location of many of the cathedrals and churches of today. In places such as the Far and Near East, pilgrimage has been and still is a particularly important religious act.

What is suggested by the monument at Thornborough is the way the henges themselves cut out the exterior world. Pilgrim centres are often separated from every day life, they are in their own unique landscape. This is precisely the case at Thornborough.

Image: Distribution of stone axes at Thornborough. After Harding.

Pilgrimage centres today are places that habitually display architecture in the form of the monument. Whether Christian or from other beliefs, all pilgrimage centres have an exceptional and unique significance. They stand out from the norm – the same may be said about the Thornborough henges. They often span entire landscapes, they also create routeways – links to other pilgrimage sites. Furthermore, they typically require many different spaces for the people who visit. Perhaps this is precisely what can be seen in the other monuments within the Sacred Vale.

Image: Thornborough henges during the Late Bronze Age showing the Barrows double post alignment. By Joanne