Wincobank Hillfort, Sheffield

Why Vitrify a Fort?

Originally, it was thought that the forts had become vitrified due to an enemy attack. A theory proposed by Childe Read more

How to Vitrify a Fort

Castle Hill and Almondbury from Kirkheaton Vitrification of Hill Forts The Vitrification process Vitrification as seen Read more

Mémo : RC-Forts vitrifiés (mise à jour mai 2001).

L’énigme des forts vitrifiés

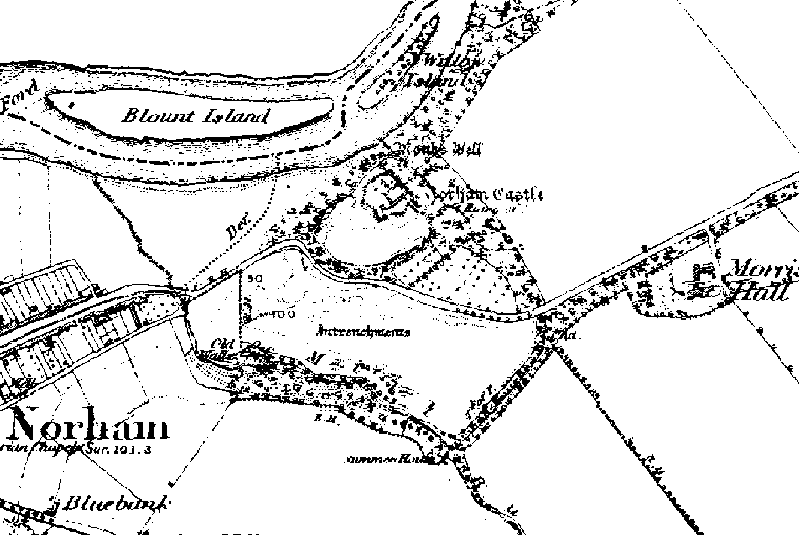

C’est lors d’un voyage en Ecosse, au cours de l’été 1997, que nous avons entendu parler pour la première fois de forts vitrifiés. C’était au château d’Urqhart, au sud d’Inverness. Les monuments historiques fermant tôt, dans ce pays, nous ne pûmes voir que de loin cette impressionnante forteresse en ruine du XIIe siècle qui domine la rive occidentale du Loch Ness. Nous nous contentâmes juste de faire des photos au téléobjectif depuis le parking et de lire les panneaux retraçant l’historique du site. Sur l’un d’eux, la mention selon laquelle le château faisait partie de l’«ensemble des forteresses vitrifiées des Iles Britanniques » nous intrigua sans que nous puissions étudier de visu le phénomène de « vitrification ».

De retour en France, cette question nous préoccupa. Nous avions le vague souvenir d’avoir entendu parler de « forteresses vitrifiées » par le passé, sans pouvoir déterminer la source de cette information. Nous nous mîmes donc à tenter d’en apprendre plus sur le sujet mais nous dûmes rapidement nous rendre à l’évidence : il semblait être totalement ignoré des archéologues de notre pays alors que, de l’autre côté de la Manche, on fait référence aux forts vitrifés, presque comme s’il s’agissait d’une banalité.

En effet, au même titre que sur le panneau du château d’Urqhart, plusieurs ouvrages, achetés sur place, font assez souvent référence, sans cependant s’y étendre démesurément, à des « forteresses vitrifiés » [Vitrified hillforts]. C’est le cas, par exemple, de Scotland BC (« L’Ecosse avant J.-C »), dont un chapitre, consacré aux forteresses préhistoriques, aborde la question :

« Quand les premières fortifications écossaises furent-elles construites ? Il s’agit d’une question apparemment simple – mais pratiquement impossible à résoudre . Notre appréciation moderne de ce que l’on peut considérer comme des « défenses » peut ne pas recouvrir celle des peuples préhistoriques (…). Notre jugement repose sur la découverte de traces structurelles et d’armes. Sur cette base, la société préhistorique apparaît comme une société relativement pacifique au moins jusqu’au début du 1er. millénaire avant J.-C., à une exception près : un ouvrage massif entouré de palissades situé à Meldon Bridge, dans les Borders, mais cet ouvrage peut avoir été réalisé aussi bien dans un but de prestige que de défense. Cependant, vers la fin de l’âge du bronze, on trouve des preuves selon lesquelles la société amorça un changement et devint plus agressive. Les forgerons qui travaillaient le bronze commencèrent à produire en grande quantité des objets comme des épées et des boucliers dont la destination ne laissait aucun doute (…). Au même moment, on commença à construire les premiers forts de caractère défensif. Certains de ces forts furent construits en pierres liées (« laced ») avec des poutres pour les renforcer ; si un tel dispositif prenait feu, que ce soit accidentellement ou suite à une attaque ennemie, et si les conditions étaient réunies, la combustion des poutres provoquait la fusion des pierres qui, de ce fait se trouvaient amalgamées, avec pour conséquences la déformation du mur (on désigne ce phénomène sous le nom de « forts vitrifiés ») .

Le phénomène des forts vitrifiés est aussi presque systématiquement signalé dans une importante collection d’ouvrages dressant l’inventaire des monuments historiques de Grande-Bretagne (éditions PENGUIN). Voici, par exemple, ce qui en est dit dans l’introduction, dans le paragraphe consacré à l’âge du fer :

« Une renaissance économique semble avoir débuté vers 600 avant J.-C. avec le début de l’âge du fer, le travail du fer, particulièrement orienté vers la fabrication de charrues, ce qui permettait le développement de l’agriculture. La grande majorité des établissements de l’âge du fer visibles de nos jours étaient entourée de défenses. Les défenses atteignant les 375 m² sont appelées « dun ». Lorsque, bien que d’une technique comparable, elles couvrent une surface supérieure, on les appelle « forts ». Ces fortifications occupent généralement un promontoire, par exemple Brough of Stoll on Yell (Shetland), une hauteur, par ex. Craig Phadrig, Inverness, ou quelquefois un tertre, par ex. Dun-da-Lamh, près de Laggan (Badenoch and Strathspey), ou encore une île : Dun an t-Siamain, près de Carinish, sur l’île de North Uist (Western Iles). Leur dénominateur commun est d’avoir augmenté les défenses naturelles du site par la construction d’un rempart qui incorpore parfois un appareillage de poutres de bois, ce qui, si le feu est MIS à l’ensemble, soit par accident ou volontairement par des attaquants, peut déterminer un incendie d’une telle intensité qu’il provoque une fusion des pierres qui se transforment alors en une masse vitrifiée, comme c’est la cas à Craig Phadrig ou à Dun Ladaigh, vers Ullapool (Ross and Cromarty) (…) » .

Mais, en France, même dans les milieux archéologiques, nous n’avons rencontré que très peu de personnes ayant entendu parler du phénomène de vitrification et encore moins à s’y être intéressés. Le premier ouvrage dans lequel nous avons trouvé une amorce de réflexion sur ce sujet est un livre destiné au grand public de Jean MARKALE, auteur d’un grand nombre d’ouvrages sur les Celtes :

« Un autre système est assez curieux : il remonte dans le temps, puisqu’on a commencé à l’employer à la fin de l’âge du bronze, c’est-à-dire aux environs de 800 avant notre ère. Il s’agit du procédé dit de vitrification. On a longtemps cru qu’il s’agissait d’un phénomène déclenché par l’incendie d’une forteresse au cours d’un combat, mais en fait, cette vitrification a été provoquée délibérément pour des raisons tactiques. Le noyau du rempart est constitué par une masse calcinée très dure et entièrement compacte, formée de pierres et de sable, ce qui donne au résultat un aspect très proche du verre épais et grossier. Cette calcination n’a pu se produire que sur place, après qu’on eut mélangé du bois aux matériaux entassés et qu’on y eut mis le feu. C’est une technique que les archéologues reconnaissent comme difficile à réaliser, mais qui a l’avantage incontestable d’assurer un rempart d’une solidité à toute épreuve, comme dans le fameux camp de Péran, non loin de Saint-Brieuc (Côtes d’Armor), qui reste un modèle du genre. »

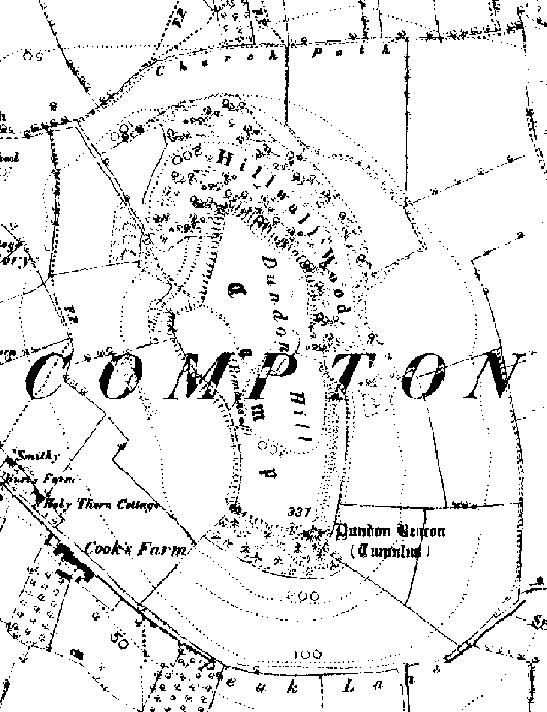

Ayant eu l’occasion d’aller en Bretagne, au cours de l’été 1998, nous avons saisi l’occasion pour nous rendre à Péran. Le site, très facile d’accès, à la différence de beaucoup d’Oppida que nous avons visités depuis, se trouve sur butte peu élevée, à quelques kilomètres du village de Plédran. A la sortie de l’agglomération, les panneaux routiers indiquent soit « camp romain » soit, encore plus curieusement « camp viking ». Sur le site même, des panneaux explicatifs, réalisés par le Centre archéologique de Péran (C.A.P.), font référence à une « destruction du camp par les Vikings ». On a en effet trouvé sur le site plusieurs objets attribués aux Vikings, « près du rempart ». Ces objets provenant de Grande Bretagne, en particulier des pièces de monnaies frappées à York vers le Xe. Siècle, on en a déduit, un peu hâtivement à notre avis, que le site, bien antérieur au Xe siècle puisque remontant à l’âge du fer, avait été détruit par les Vikings. Ce qui est plus étonnant, c’est qu’aucun de ces panneaux ne fait la moindre allusion au phénomène de vitrification, pourtant patent, comme on va le voir.

Le camp, de forme circulaire, se développe sur une circonférence d’environ 200 mètres. Une levée de terre est couronnée par les vestiges d’un mur dont les pierres sont littéralement fondues ensemble. Péran, pour reprendre les termes de Jean MARKALE, est effectivement un « modèle du genre ». De cela, nous pouvons en témoigner après avoir vu d’autres vestiges de forts vitrifiés beaucoup moins significatifs. Ici, le phénomène de vitrification saute aux yeux : on l’observe sur l’ensemble du rempart. Les pierres, d’origines géologiques diverses (mais toutes des roches dures : quartzites, dolérites, aplites ) sont fondues et collées entre elles (certaines ont même coulé, se transformant en un magma solidifié rappelant de la lave volcanique ) pour former une seule masse compacte.

Une partie du rempart a été reconstituée par les archéologues selon la technique du « murus gallicus ». Cette méthode, décrite par César dans la Guerre des Gaules, et attribuée par lui aux Gaulois (mais nous savons maintenant qu’elle remonte au moins à l’âge du fer), consistait à alterner poutres de bois et pierres.

M. Jean-Louis PAUTE, président du C.A.P., à qui nous nous étions adressé pour obtenir plus d’explications sur le site, nous a aimablement fait parvenir une brochure, éditée en 1991, qui retrace l’historique des recherches à Péran et leurs conclusions. Alors que, nous l’avons vu, aucune mention n’était faite de vitrification in situ, le texte de la brochure aborde largement le phénomène. Force est même de constater qu’il fut à l’origine de l’intérêt des archéologues du XIXe siècle pour cet Oppidum, comme il le fut, d’ailleurs, nous l’avons constaté depuis, pour la plupart des oppida vitrifiés connus. Le site date, à l’origine, de l’âge du fer et son occupation a duré jusqu’à l’époque carolingienne. Selon les archéologues l’ayant étudié, l’oppidum aurait été détruit par les Vikings vers 905-925 après J.-C. Leur hypothèse, pour expliquer la vitrification du rempart, est classique : pour eux, il ne fait aucun doute que l’incendie du « murus gallicus », mis à feu lors du sac de l’oppidum, est le seul responsable du phénomène de vitrification . A l’appui de leur affirmation, les auteurs invoquent les datations obtenues par le Carbone 14 et l’archéomagnétisme. On sait toutefois depuis quelques années, particulièrement pour le C 14, que l’on ne peut plus avoir une confiance aussi absolue dans ses indications, en particulier dans le cas où de fortes températures ont été en jeu ; il est en effet désormais admis que de telles circonstances ont pour conséquence de rajeunir démesurément les datations obtenues .

Mais un autre constat nous fait prendre ces datations avec précautions : en effet, si la destruction de Péran remontait au Xe siècle, son cas serait unique car ce serait la vitrification la plus récente que l’on connaisse ! Quant à l’affirmation selon laquelle le phénomène qui a transformé le rempart de Péran en un magma vitreux serait imputable à la combustion du poutrage interne, on verra qu’il s’agit d’une allégation gratuite, sans doute bien pratique pour « expliquer » l’une des plus grandes énigmes de l’archéologie, mais qu’elle est totalement contredite par l’expérimentation.

L’un des rares ouvrages français qui aborde la question de la vitrification de remparts de l’âge du fer, « Villes, villages et campagnes de l’Europe celtique » , nous apprend que cette question a préoccupé, depuis plus d’un siècle, de nombreux archéologues. Certains, et non des moindres , ont même essayé de reproduire le phénomène à grand renfort de moyens techniques, mais la plupart on dû reconnaître leur échec :

« La toponymie, les légendes populaires, et encore aujourd’hui la littérature archéologique font une large place aux « enceintes vitrifiées » ou « calcinées ». Dans la masse des remparts de pierre écroulés, des « noyaux de chaux » ou des blocs fondus et soudés par la chaleur ont été découverts sur environ 150 sites. La plupart d’entre eux se trouvent en Ecosse et dans le Massif central . Ils ont excité la curiosité des chercheurs, et des hypothèses de toutes sortes ont été émises pour expliquer ce phénomène.

« Au début du XIXe siècle, leur origine a été attribuée aux feux qu’auraient allumés les guetteurs pour transmettre des nouvelles à la ronde. En effet les auteurs de cette époque sont très préoccupés des relations d’enceinte à enceinte, et chaque description du site s’accompagne de considérations sur la surveillance du territoire. Une hypothèse plus audacieuse attribue les vitrifications à la foudre, qui aurait ainsi eu une prédilection particulière pour les remparts préhistoriques. Enfin certains auteurs imaginent qu’il s’agit d’une technique mise au point pour augmenter la cohésion des matériaux du rempart. Même si la réalisation d’un tel projet dans des roches cristallines suppose une quantité de bois considérable, il est facile de concevoir l’intérêt du procédé qui permettrait d’avoir un rempart plus solide qu’un mur en béton. En revanche, les noyaux de chaux, que des auteurs comme Drioton croyaient avoir reconnus au cœur de talus érigés dans des régions calcaires, semblent d’un intérêt plus limité.

« En 1930, G. Childe parvient à fondre des blocs au cours d’une expérience sur une reconstruction, mais le choix des matériaux utilisés a été critiqué. Youngblood montre en 1978 que la combustion de l’armature de bois d’un rempart à poutrage interne ne peut pas provoquer de vitrification si un feu n’a pas été délibérément provoqué et entretenu dans ce but. I. Ralson reprend l’expérience en 1981 avec un rempart long de 9 m, large de 4 et haut de 2,40 m. Il le garnit intérieurement de poutres horizontales entrecroisées, dont les têtes dépassent en façade. Plusieurs camions de bois ont été déversés devant le parement et enflammés. La température au cœur du rempart ne s’est élevée que très lentement. Elle s’est effondrée chaque fois que le vent, au lieu de rabattre les flammes vers le rempart, les éparpillait dans les autres directions. Dans les restes du rempart disloqué par la chaleur, quelques fragments vitrifiés ont pu être recueillis. Il est donc bien clair qu’il faut un feu intense, bien entretenu dans des conditions météorologiques favorables, pour obtenir une vitrification (…).

« Dans tous les cas qui ont pu être étudiés jusqu’à maintenant, l’action du feu ne laisse jamais de traces régulières, systématiques, qui pourraient seules être interprétées comme la preuve de l’emploi d’une technique de construction basée sur la combustion de la roche . Il s’agit toujours d’observations localisées ou de traces irrégulières, jamais d’un parement vraiment soudé par le feu. De plus I. Ralston a montré que la carte des enceintes vitrifiées ou calcinées correspondait assez exactement à la répartition des enceintes à poutrage interne, de la protohistoire jusqu’au Moyen Age .

« S’agit-il alors des traces de l’attaque des habitats fortifiés ? La technique de siège la plus répandue avant l’intervention romaine consiste en effet à cribler de projectiles le sommet des remparts pour en déloger les défenseurs, puis à mettre le feu aux portes avant de se ruer à l’intérieur. Il est peu vraisemblable que, en pleine action, les assaillants aient eu le loisir d’entretenir un feu suffisamment intense pour obtenir des vitrifications qui réclament, l’expérience l’a montré, beaucoup de combustible et un vent favorable. Certaines enceintes écossaises sont d’ailleurs vitrifiées sur tout leur pourtour . Nous imaginons volontiers que la vitrification est le produit d’une destruction systématique des fortifications de l’adversaire après la prise et souvent le pillage de la place, pour bien marquer le caractère irrémédiable de la défaite. »

On regrettera que cette intéressante analyse, l’une des plus développées que nous ayons pour l’instant trouvées sur le sujet, ne fasse référence à aucun site précis , si ce n’est pour leur dénier la qualification d’enceintes «vitrifiés » (i.e. le camp de Myard et du Châtelet d’Etaules, fouillés par J.-P. Nicolardot , en Bourgogne ), ni ne renvoie, dans la bibliographie citée, à aucune étude de référence sur la question…

En conclusion, il semblerait que toutes les tentatives qui ont à ce jour été faites pour tenter de reproduire le phénomène de vitrification se soient soldées par un échec. La raison en serait que la température obtenue, si elle a permis de rubéfier les pierres, n’a cependant jamais été suffisante pour les vitrifier, sauf sur de toutes petites surfaces.

D’après les géologues consultés , la vitrification de matériaux comme le granite ne peut se produire en dessous de à 1000°. Une telle montée en température ne semble pas pouvoir être atteinte à l’air libre mais seulement à l’intérieur d’un four. Comment imaginer qu’on ait construit un four tout autour d’une enceinte de pierres de plusieurs centaines de mètres (Péran fait partie des « petits » oppida mais il en existe de beaucoup plus étendus…). Cela exclut de facto l’incendie accidentel.

Penchons-nous un instant sur l’hypothèse, défendue par certains , selon laquelle la vitrification aurait été obtenue volontairement pour solidifier l’ensemble. Voire… Nous avons nous-même constaté que, si certaines parties de remparts étaient en effet rendues plus résistantes par la vitrification, d’autres, au contraire, avaient été fragilisées, en particulier lorsque, dans le magma, on trouve des noyaux de chaux, résultante de la combustion du calcaire… Le mur, au lieu d’être renforcé, s’effondre alors.

Une autre hypothèse, que nous n’avons trouvé évoquée par quiconque, serait l’utilisation d’un produit chimique dont on aurait enduit les pierres et qui, mis à feu, aurait dégagé une chaleur supérieure à 1000°. Reste à savoir quel produit aurait pu être utilisé ? Reste aussi à comprendre la raison qui aurait poussé nos ancêtres de l’âge du fer à vitrifier (volontairement) leurs oppida ou ceux de leurs ennemis.

Voici pour les faits. Aucune explication rationnelle ne pouvant à ce jour être obtenue par l’archéologie, nous rappelant que les oppida vitrifiés se trouvaient, de par leur ancienneté et leur situation, liés à l’aire celtique, et nous souvenant de l’intéressante réflexion initiée par Jean MARKALE à propos de Péran, nous avons décidé d’aller voir d’un peu plus près du côté de la mythologie celtique si elle pouvait nous apporter des pistes inédites.

« Il faut d’ailleurs voir dans ce procédé de vitrification l’origine des traditions concernant l’Urbs Vitrea, Care Gwtrin et autres lieux du genre Royaume de Gorre, c’est-à-dire des « Cités de Verre » qui se rencontrent si souvent dans les romans arthuriens et d’une façon générale dans toutes les traditions mythologiques irlandaises ou bretonnes. Les « Villes Blanches » de la tradition orale, qui désignent toutes d’anciennes forteresses ruinées, sont un souvenir évident de cette technique, par ailleurs parfaitement oubliée. »

Si Jean MARKALE a raison, si toutes les « cités de verre », « châteaux de verre » (et leurs variantes) des légendes celtiques signalent d’anciens « forts vitrifiés », les voies de recherche sont immenses !

Nous commencerons par le site le plus occidental de l’aire celte où l’on ait signalé des vestiges de vitrifications : l’Ile de Tory, située au large de la côte ouest de l’Irlande. Cette île doit son nom à une tour, l’une de ces nombreuses round towers (« tours rondes ») qui se dressent encore par centaines sur l’Ile Verte (ainsi qu’en moindre quantité en Ecosse) et dont on n’a jamais réussi à ce jour à savoir quel en avait pu être l’usage véritable. Généralement, on les date des tout débuts de l’ère chrétienne et on les relie à l’existence des premiers monastères ; on suppose qu’elles ont pu servir de tours de guet ou qu’elles servaient à entreposer le trésor des monastères menacés par les raids des Vikings. Comment, alors, on-t-elle résisté alors que les monastères qui les entouraient ont été détruits ? L’extraordinaire qualité de leur architecture, faite de pierres magnifiquement appareillées, explique sans doute en partie le mystère. Le fait est qu’une de ces tours a tellement marqué l’histoire de cette petite île que l’île elle-même a pris le nom de la tour (Tor-Inis signifie « Ile de la Tour »). Voici ce que nous avons pu lire à son sujet :

« La tour de l’île de Toriniz, aujourd’hui île Tory (…), d’âge si vénérable, n’existe plus en tant que bâtiment. Toutefois, elle perdure encore, ou du moins perdurait au siècle dernier, en tant que ruines. Le grand étonnement des archéologues fut de constater que ces vestiges étaient vitrifiés. Quelle peut être la raison de cette vitrification ? » .

Or, c’est précisément sur cette île que, selon la tradition mythologique irlandaise, les Fomoire (ou Fomore), avaient installé leur camp de base et c’est de là qu’ils lançaient leurs expéditions militaires sur l’Irlande. Ce peuple mythique était composé de géants maléfiques, à la fois alliés, par des liens familiaux complexes, et néanmoins ennemis, des Tuatha de Danaann (les « enfants de la déesse Dana ou Ana »). Aucun de ces deux peuples n’était autochtone ; ils venaient tous les deux des « Iles du Nord du Monde », endroit mythique situé dans l’extrême nord dont on ne sait pratiquement rien. Les uns et les autres étaient dotés de puissants pouvoirs, réputés magiques pour nos ancêtres mais que nos connaissances techniques actuelles nous rendent familiers.

L’un des chefs des Fomores, le géant Balor, par ailleurs grand-père du « dieu » Lug, un des Tuatha de Danaann, vivait sur Toriniz. De là, il envoyait un puissant flux d’énergie de l’autre côté du bras de mer qui le séparait de la terre d’Irlande pour foudroyer ses ennemis. Les descriptions que l’on a de Balor évoquent plus une machine qu’un être vivant : on le compare à un cyclope dont l’œil unique émettait un rayon qui réduisait en cendres ses ennemis : « C’est un géant effrayant dont l’unique œil foudroie toute une armée lorsqu’il soulève les sept paupières qui le protègent ». Cet « œil » extraordinaire devait être maintenu ouvert grâce à des crochets métalliques soulevés par plusieurs aides. Lors de l’une des trois batailles de Mag Tured qui se déroulèrent en Irlande entre les Fomore et les Tuatha de Danaann, le dieu Lug réussit à neutraliser l’œil maléfique de Balor en utilisant sa lance personnelle, que les textes appellent « lance d’Assal », l’un des quatre objets magiques rapportés des Iles du Nord du Monde . Cet objet avait lui aussi des propriétés étranges : il ne manquait jamais son but et devait être refroidi dans un chaudron rempli de sang humain .

Jean MARKALE, dans Les Celtes et la civilisation celtique, donne plus de détails sur cet instrument fabuleux :

« Lug est le possesseur d’une lance magique qui fait penser aux flèches à la fois meurtrières et guérisseuses d’Apollon. Elle s’appelle Gai Bolga . C’est l’emblème de l’éclair. Elle provient d’Assal, une des îles du nord du monde (allusion à l’Hyperborée) d’où étaient originaires les Tuatha Dé Danann. Cette lance avait un pouvoir venimeux et destructeur et, pour atténuer ce pouvoir, il fallait plonger la pointe dans un chaudron rempli de poison et de « fluide noir », c’est-à-dire de sang » .

Après avoir été lancée, en utilisant un cri particulier (« ibar », qui signifie « if »), et touché son but qu’elle ne ratait jamais (« sa valeur est telle qu’elle ne frappe pas par erreur ») elle revenait d’elle même dans la main du dieu grâce à un autre cri, « athibar » : « elle revient en arrière jusqu’à la main qui l’a lancée » .

Qu’était donc cet objet ? Quelles techniques étaient-elles utilisées par Balor et par Lug pour se faire la guerre ? N’est-il pas étrange que la Tour de Toriniz, l’endroit précis où résidait le géant Balor, ait été vitrifiée ?

Depuis la première version de ce mémo (10/12/98), nous avons eu connaissance des travaux de RALSTON sur les oppida du Limousin et, pendant l’été 1999, nous sommes allés dans la Creuse pour tenter de voir quelques uns des sites cités dans cet ouvrage comme portant des traces de vitrifications. Nous avons dû constater que le travail de RALSTON, qui est l’un des inventaires les plus complets qui soient sur les forteresses de l’âge du fer en France, fait une large place au phénomène de vitrification. Malheureusement, sur place, l’accès aux sites est souvent rendu difficile par une végétation débridée et un manque d’entretien flagrant.

Nous dûmes ainsi renoncer à nous rendre sur certains oppida que nous avions envisagé de voir en raison d’indications trop imprécises (ce fut le cas pour nous aux Muraux, commune de St. Georges de Nigremont). D’autres oppida, où l’on avait par le passé signalé des vitrifications, ont été détruits par une urbanisation sauvage et le manque de contrôle des instances dont ce devrait être le rôle: c’est déjà le cas de celui de Thauron qui ne bénéficie d’aucune mesure de protection. Lors de notre visite, nous avons même vu un brave homme démolir allègrement un mur de pierres qui se trouvait sur sa propriété et qui, d’après nos indications, était vraisemblablement l’un des seuls vestiges de l’oppidum…

Les autres sites visités, pour n’être pas urbanisés, n’en sont pas pour autant mieux protégés. C’est le cas du fameux Puy de Gaudy, au-dessus du village de Ste. Feyre, au sud de Guéret, qui est le lieu de rendez-vous de promenade favori des pensionnaires de la maison de retraite de la MAIF située juste au-dessous et surtout des « VTTistes » qui franchissent sans sourciller les murailles de l’oppidum. Dans ce département, pourtant fort riche en vestiges archéologiques et historiques, rien ne semble fait par les autorités pour protéger les sites dont elles ont la responsabilité (sur aucun des oppida visités nous n’avons vu la moindre mention « site archéologique » ni la moindre interdiction !).

Au cours de ces visites, par ailleurs assez décevantes pour les raisons que nous avons indiquées, nous n’avons relevé que peu de vitrifications indiscutables. Ce fut le cas sur l’un des sites, qui n’était pourtant pas réputé comme le plus représentatif : l’oppidum de Châteauvieux à Pionnat qui fait face au Puy de Gaudy. Elles sont pourtant tout-à-fait remarquables et indiscutables, mais le site, outre le fait qu’il n’est pas indiqué, est situé dans un bois à la végétation inextricab le. Nous avons pu cependant constater le même phénomène qu’à Péran : les pierres étaient littéralement « cimentées » entre elles par leur surface, certaines avaient fondu et s’étaient transformées en véritable « lave ». Sur place, la théorie lue ou entendue à propos de plusieurs sites, selon laquelle ces pierres vitrifiées étaient du machefer résultant d’un processus de fonte de métaux dans des haut-fourneaux répartis le long du rempart ne tient pas.

En effet, à Pionnat, nous avons compris comment l’on pouvait confondre certains éboulements du rempart, qui forment une sorte de voûte cimentée par la vitrification des pierres, avec le cul-de-four d’un haut-fourneau. Cette confusion, excusable pour des non-spécialistes cherchant à tout prix une explication satisfaisant le bon-sens, ne l’est plus lorsqu’on la lit sous la plume d’archéologues officiels. Il suffit pour cela d’observer le rempart dans sa continuité pour s’apercevoir que ce que l’on a pris un peu vite pour des vestiges de hauts-fourneaux ne possède aucune des structures nécessaires au fonctionnement d’un tel dispositif (prise d’air, etc.). Il s’agit bien, purement et simplement, d’une « bulle de lave » comme on en observe dans les formations volcaniques naturelles, sauf que, dans le cas qui nous occupe, nous avons affaire à une construction qui a été artificiellement vitrifiée et non à un phénomène naturel.

Depuis ce voyage dans la Creuse, nous avons bien entendu poursuivi nos investigations qui nous ont permis d’identifier avec certitude d’autres forts vitrifiés, en particulier deux dans la région de Roanne (en mai 1999), et un autre dans l’Allier (en mai 2000).

Nous avons trouvé que l’aire d’extension de ces structures, que nous pensions au départ limitée aux Iles Britanniques, était beaucoup plus large puisqu’elle s’étend sur une grande partie de l’ère dite celtique, bien que chronologiquement antérieure à l’arrivée des Celtes en Europe de l’Ouest, puisque remontant à l’âge du fer.

Bibliographie

– Françoise AUDOUZE et Olivier BUCHSENSCHUTZ (1989): Villes, villages et campagnes de l’Europe celtique. Paris, Hachette, 1989 (collection Bibliothèque d’archéologie), pp. 120-121.

– Base Mérimée (Ministère de la Culture) ;

– Les Celtes (1997), ouvrage collectif publié sous la dir. De Sabatino Moscati à l’occasion de l’exposition Les Celtes au Palazzo Grassi à Venise, 1991. Paris, Stock, 1997.

– Gordon CHILDE : Excavations of the vitrified Fort of Finavon, Angus.

– John GIFFORD (1992): The buildings of Scotland : Highland and Islands London, Penguin Books, 1992.

– Guide Bleu Bretagne, Paris, Hachette, 1992.

– Guide Bleu Grande-Bretagne. Paris, Hachette, 1990 (réed. 1994).

– Guide du Routard Ecosse 1996-1997. Paris, Hachette, 1995.

– E. KOARER-KALONDAN et GWEZENN-DANA (1973) : Les Celtes et les extra-terrestres. Verviers, Marabout, 1973 (ouvrage épuisé).

– KOUSNETSOV, IVANOV et VELETSKY (1989): « Effects of fires and biofractionation of carbon isotopes on results of radiocarbon dating of old textiles », in : Actes du symposium scientifique international du CIELT, Paris, 1989.

– Jean MARKALE (1997): Petite encyclopédie du Graal. Paris, Pygmalion, 1997.

– Jean MARKALE (1992): Les Celtes et la civilisation celtique. Paris, Payot, 1969 (rééd. 1992).

– Sabine MARCILLE (1999) : « Civilisation celtique : ces étranges cités vitrifiées », in : Efferve-Sciences, n°11 (1999).

– J.-P. NICOLARDOT (1991): Le Camp de Péran, Saint-Brieuc, Centre archéologique de Péran, 1991.

– Jean-Paul PERSIGOUT (1985): Dictionnaire de mythologie celte. Paris, Ed. du Rocher, 1985 (rééd. 1990).

– Ian B.M., RALSTON (1992) : Les enceintes fortifiées du Limousin. Paris, éd. De la Maison des Sciences de l’Homme, 1992 (Documents d’Archéologie Française, n°36).

– Anna RITCHIE (1988) : Scotland BC Edinburgh, 1988 (rééd. 1994), H.M.S.O. (coll. Historic Scotland).

– Divers sites Internet anglais, le plus complet (pour les sites britanniques) étant : Prehistoric Web Sites..

Remerciements

Nous remercions :

– Notre frère Yvon COMTE, Documentaliste à la Direction Régionale des Affaires Culturelles Languedoc-Roussillon, pour nous avoir indiqué quelques forts vitrifiés recensés en France au titre des Monuments Historiques. C’est aussi grâce à ses recherches sur Internet que nous avons eu connaissance du site anglais Prehistoric Web Sites qui donne, à notre connaissance, la liste la plus étendue de forts préhistoriques des Iles Britanniques (dont un certain nombre sont vitrifiés). Nous lui devons aussi de nous avoir mis en contact avec Michel WIENIN, chargé de l’étude du patrimoine industriel à l’Inventaire Général, Direction des Affaires Culturelles Languedoc-Roussillon, qui nous a proposé de faire analyser certains échantillons de vitrifications recueillies par nos soins par l’Ecole des Mines d’Alès. Nous attendons avec impatience le résultat de ces analyses…

– Denise BONJOUR, éternelle chercheuse aux frontières du réalisme fantastique, qui nous a adressé une copie d’un article récent de Sabine MARCILLE (1999). Outre que nous avons ainsi l’impression de nous sentir moins seuls, nous y avons trouvé quelques nouveaux sites qui ont enrichi notre documentation.

– Michel ROUVIERE, pour nous avoir retrouvé d ans sa bibliothèque Le livre des secrets trahis de Robert CHARROUX, livre que nous avions eu en main il y a bien des années et où nous avions entendu pour la première fois parler de « Cités vitrifiées ».

– Merci aussi à tous ceux dont les indications sur place nous ont permis de visiter certains oppida difficiles à trouver, en particulier : Mme DUQUESNE, à Lussac-les-Châteaux (86), M. Eugène MAZEROLLES (à Bègues, Allier), qui nous a offert quelques échantillons de vitrifications prélevées sur sa propriété, les mairies de St. Alban-les-Eaux et de Villerest (42) ainsi que tous les anonymes qui ont bien voulu nous consacrer un peu de leur temps.

INVENTAIRE DES FORTS VITRIFIES

(mise à jour août 2000)

– ECOSSE (10 sites)

1.1. An Cnap (Iles d’Arran) (source : site internet des Iles d’Arran) ;.

1.2. Barry Hill (Allyth, Perthshire) (“All that remains of this vitrified fort are a massive tumbled stone wall and subsidiary ramparts”, site internet d’Alyth);

1.3. Craig Phadrig, département d’Inverness (« Two vitrified walls enclose an area 75m by 25m. The inner wall stands 1.2m high on the inside”, site internet easyweb.easynet);

1.4. Dun Deardail (vers Lochaber, ouest de l’Ecosse) [source : site internet de Lochaber] ;

1.5. Dun Lagaidh, commune de Ullapool, département de Ross & Cromarty ) (« Massive stone rampart of the 1st millenium BC, now vitrified and so originally timber-laced (…)” [Source : HAI];

1.6. Finavon (Angus) [Source : CHILDE, 1935];

1.7. Knock Farril, commune de Strathpeffer, dépt. Ross & Cromarty, (Oblong hilltop fort of the 1st millenium BC, its stone rampart heavily vitrified so presumably originally laced with timber » ; Source : HAI);

1.8. Tor a’Chaisteal Dun, Ile d’Arran (Irlande) ;

1.9. Urqhart Castle (près d’Inverness) ;

1.10. White Caterthun (Incidemment signalé par RALSTON, 1992 comme étant vitrifié à propos du site français du Camp de César à CHATEAUPONSAC, Hte.-Vienne).

2) IRLANDE (1 site)

2.1.Tour de Toriniz, Tory Island (Irlande). Voir ce qui en est dit dans le texte ci-dessus..

3) FRANCE ( plus de 70 sites recensés, dont au moins une 20e vitrifiés)

3.1. Allier (03)

3.1.1. BEGUES : Oppidum de Bègues (« Rempart vitrifié », RALSTON, 1992). Une visite, en mai 2000, nous a permis d’obtenir la preuve de la vitrification. Echantillons prélevés .

3.2. Cantal (15)

3.2.2. COREN : Puy de la Fage [RALSTON (1992), p. 124]. Confusion possible avec La Fage-Montivernoux (Lozère).

3.2.3. ESCORAILLES : Pas de lieu-dit. [RALSTON (1992), p. 124].

3.2.4. LA COURBE : « Le Château Gontier ». Attention ! : risques de confusion avec La Courbe, près d’Argentan (Orne).

3.2.5. MAURIAC (a) : « Vieux Château », hameau d’Escoalier* (« Certains indices laissent à penser que les deux communes voisines peuvent avoir chacune une enceinte vitrifiée », RALSTON, 1992). * Confusion possible avec Escorailles (voir ci-dessus).

3.2.6. MAURIAC (b)

3.2.7. MAURIAC (c)

3.3. Charente (16)

3.3.1. MOUTHIERS-SUR-BOEME : Pas de lieu-dit [RALSTON (1992), p. 124].

3.3.2. VOEIL ET GIGET : « Camp des Anglais ou de la Pierre Dure » (« Traces de calcination sur toute la longueur du talus, 210 m de long, 5-6 m de haut et 25 m de large. La surface de cet éperon barré couvre 3 ha env. », RALSTON, 1992). Bien qu’on ne parle que de « calcination », le toponyme de « Pierre Dure » pourrait être un indice de vitrification.

3.3.3. SOYAUX : « Camp de Recoux ». [RALSTON (1992), p. 124].

3.4. Cher (18)

3.4.1. LA GROUTTE : « Camp des Murettes » (ou « de César »). « S’étend sur 4 ha. » [RALSTON (1992), p . 124].

3.5. Corrèze (19)

3.5.1. LAMAZIERE-BASSE : « Champ du Châtelet » au lieu-dit Les Bessades (« Pierres vitrifiées dans l’éboulement à l’extrémité orientale du mur intérieur. Autres gneiss vitrifiés, non seulement dans l’éboulis du rempart mais également à l’extrémité orientale du mur à l’extérieur. La vitrification semble être limitée à cette partie du site », RALSTON (1992), pp. 46-47. Dans sa bibliographie, l’auteur renvoie à VAZEILLES : Station vitrifiée avec muraille vitrifiée du Châtelet, commune de Lamazière-Basse (Corrèze).)

3.5.2. MONCEAUX S/DORDOGNE : « Puy de la Tour » ou « du Tour » (« Un bloc de pierre vitrifiée », RALSTON (1992), pp. 49-53).

3.5.3. MONCEAUX S/ DORDOGNE : « Puy Grasset » ou « Granet » au lieu-dit « Le C(h)astel » ou « le Chastelou » au village de Raz. « Quelques traces de vitrifications visibles dans les roches schisteuses du sommet de la motte (qui serait d’époque médiévale ». « Desbordes décrit l’enceinte comme vitrifiée et, sans doute, médiévale ». [RALSTON (1992), p. 53]

3.5.4. ST. GENIEZ-Ô-MERLE : « Puy de Sermus » ou « Vieux Sermus ». (« L’indice principal de fortifications consistait en un tronçon de mur vitrifié, haut de 1,5 m et long de 3 m, situé sur le côté nord-ouest du site où l’accès était le plus facile. (…) Les défenses reconnaissables consistaient en deux tronçons de murs vitrifiés avec une pente artificielle à l’extérieur. (…) Une fouille sur le côté nord-ouest a montré que le mur vitrifié était construit directement sur la roche, qui présentait quelques signes d’une vitrification superficielle. », RALSTON, 1992.)

3.5.5. ( ?) ST. PRIVAT : « Camp de Srmus » (ou « Sermus ») [MARCILLE, p. 17]. Il doit s’agir d’une confusion avec le précédent.

3.6. Côtes d’Armor

3.6.1. PLEDRAN : Camp de Péran [MARKALE (1997), pp. 133-135. Site visité en juillet 1998. La vitrification est patente sur l’ensemble du site, qui était parfaitement dégagé lors de notre visite. La roche est fondue et amalgamée en de gros blocs soudés ensemble. Echantillons prélevés. Voir ce que nous en disons plus haut.

3.7. Côte d’Or (21)

3.7.1. BOUILLAND : « Le Châtelet ». Sans autre précision.

3.7.2. CRECEY-SUR-TILLE : « Camp de fontaine Brunehaut » [RALSTON (1992), p. 124. Il ne dit pas s’il est vitrifié ou non].

3.7.3. CHAMBOLLE-MUSIGNY : « Enceinte de Groniot » (ou « Gromiot »). Sans autre précision.

3.7.4. ETAULES : « Le Châtelet » (« Restes carbonisés de poutres », RALSTON, 1992). On ne parle pas de vitrification. MARCILLE (1999), p. 17 cite « Le Chevalet ». Nous pensons qu’il doit s’agir d’une graphie erronée.

3.7.5. FLAVIGNEROT : « Camp de César » dit aussi Enceinte du Mont Afrique. [RALSTON (1992), p. 125].

3.7.6. GEVREY-CHAMBERTIN : « Enceinte du Château-Renard » [RALSTON (1992), p. 125].

3.7.7. MESSIGNY : « Enceinte de Roche-Château ». Pas d’autres précisions.

3.7.8. PLOMBIERES-LES-DIJON : « Enceinte du Bois brûlé » [RALSTON (1992), p. 125]. Le toponyme de « Bois Brûlé », rencontré sur d’autres sites, peut être la confirmation d’une vitrification.

3.7.9. VAL SUZON : « Le Châtelet de Val Suzon ou de la Fontaine du Chat ». « Situé juste en face du Châtelet d’Etaules, de l’autre côté de la vallée » [donné comme étant vitrifié par MARCILLE (1999), p. 17]. (« Couche brûlée », selon RALSTON (1992).

3.7.10. VELARS S/OUCHE : « Enceinte de Notre-Dame de l’Etang ». Donné comme vitrifié par MARCILLE (1999), p. 17.

3.7.11. VIX : « Mont Lassois » (« La ‘levée de terre’ méridionale (…) semble avoir été construite sur un niveau brûlé sur lequel reposent des pierres parfois rubéfiées ou calcinées », RALSTON, 1992). On ne parle pas de vitrification.

Ainsi, peut-être, que d’autres sites d’après les études de Nicolardot (cité par RALSTON, 1992).

3.8. Creuse (23)

3.8.1. AUBUSSON : « Camp des Chastres ». Traces de vitrifications [RALSTON (1992), p. 70].

3.8.2. & 3.8.3. BUDELIERE : « Promontoires de St. Marien » et de « Ste. Radegonde ». Nous nous sommes rendus sur le promontoire de Ste Radegonde en 1999 à partir des indications de RALSTON mais le site étant très embroussaillé, nous n’avons pu observer de vitrifications.

3.8.4. JARNAGES : Enceinte sous le nom de « Château ».

3.8.5. PIONNAT : Oppidum au village* de « Châteauvieux ». [RALSTON (1992), pp. 75-79]. * Le hameau de Châteauvieux est distant de Pionnat de plusieurs km. Enceinte ovale de 128 m de longueur axiale. Malgré l’embroussaillement du site, notre visite de l’été 1999 nous a permis de confirmer l’existence d’une vitrification importante, bien visible et indiscutable : plus encore qu’à Péran, les pierres sont fondues et amalgamées entre elles. On voit même des traces de coulures, comme dans le cas de laves volcaniques. La chaleur a dû être d’une intensité extrême. Certaines descriptions du site parlent de vestiges de fours à chaux ou de fours à métaux. Nous pensons qu’il s’agit d’une mauvaise interprétation des observations faites par des personnes qui n’avaient jamais vu de vitrifications. Pour nous, il ne fait aucun doute que Pionnat montre des traces patentes de vitrifications. Echantillons prélevés. Un autre site, « Ville de Ribandelle (ou Ribaudelle ») lui ferait face.

3.8.6. STE. FEYRE : « Puy de Gaudy ». Visité à la même époque. Même observation qu’à Pionnat mais la dégradation du rempart et son embroussaillement ne nous ont pas permis de constater des traces évidentes de vitrifications. [RALSTON (1992) ; base Mérimée].

3.8.7. ST. GEORGES DE NIGREMONT : « Les Muraux » (ou « le Muraud »). [RALSTON (1992), pp. 80-81. Malgré les indications de RALSTON, complétées par des indications recueillies sur place auprès des habitants qui connaissaient l’existence du site, nous n’avons pu identifier l’emplacement de l’oppidum des Muraux. Ils nous ont conseillé de contacter Monsieur EUCHER à Rouzelie, qui avait fouillé le site, ce que nous n’avons pu faire.

3.8.8. THAURON : Village. Visite décevante : inutile de rechercher des traces de vitrifications. Le site a été totalement détruit par l’extension anarchique du village, installé sur l’oppidum et rien n’est fait pour préserver ce qui pourrait en subsister.

3.9. Dordogne

3.9.1. PERIGUEUX : Enceinte du « Camp de la Boissière » située sur l’un des contreforts de la rive droite de l’Isle en face de Périgueux. Ne pas confondre avec Périgneux (Loire).

3.9.2. ST. MEDARD D’EXCIDEUIL : « Castel Sarrazi » à Gandumas (« Au moins deux ouvrages distincts et profondément vitrifiés sont conservés (…). Les traces de la position originelle du poutrage ont été reconnues dans la masse vitrifiée (…). » [RALSTON (1992)]. Même observation à Péran.

3.10. Doubs (25)

3.10.1. MYON : « Châtelet de Montbergeret » [RALSTON (1992), p. 126].

3.11. Finistère (29)

3.11.1. ERGUE-ARMEL : « Berg-ar-Castel » [RALSTON (1992), p. 126]. Rien n’indique que ce site soit vitrifié.

3.11.2. HUELGOAT : « Camp d’Arthus ». « Rempart massif secondaire, non daté, recouvrant un murus gallicus de type Avaricum. » [RALSTON, 1992, p. 132]. Site visité au cours de l’été 1998. Malheureusement l’étendue du site, par ailleurs très embroussaillé, ne nous ont pas permis d’étudier si certaines parties montraient des traces de vitrifications.

3.11.3. LOSTMARC’H (près de CROZON). [Les Celtes, p. 586].

3.12. Ille-et-Villaine (35)

3.12.1. VIEUX-VY-SUR-COUESNON : « Oppidum d’Orange » [RALSTON (1992), p. 126.

3.13. Jura (39)

3.13.1. SALINS : « Camp du Château-sur-Salins ». « Matériau calciné sur environ 4 m de long sur le côté ouest du rempart préhistorique (…). » [RALSTON (1992), p. 127].

3.14. Loire (42)

3.14.1. PERIGNEUX : « Pic de la Violette » (« Un plateau à 650 m d’altitude est décrit comme partiellement enclos par de faibles murailles et des blocs vitrifiés », [RALSTON (1992), p. 127]. Ne pas confondre avec Périgueux (Dordogne).

3.14.2. ST. ALBAN-LES-EAUX : « Châtelus » [ ou « Châtelux », chez RALSTON, 1992, graphie manifestement erronée]. (« Matériaux vitrifiés retrouvés sur place », RALSTON, 1992). Visite superficielle du site en mai 1999, les broussailles et la mousse recouvrant les pierres m’ont empêché d’identifier tout vestige de vitrification. Cela ne veut pas dire qu’il n’y en ait pas. Sur place, les gens connaissent le site sous le nom de « Château de verre », appellation qui me paraît suffisamment significative pour qu’on puisse admettre ce site dans la liste des vitrifications (voir MARKALE).

3.14.3. VILLEREST : « Le Château-Brûlé » à Lourdon. Visite à Villerest en mai 1999. Je n’ai pu accéder au site mais la mairie m’a communiqué le résultat de fouilles effectuées par Stéphane Boutet (cité par MARCHAND, 1991), qui confirme l’existence d’un « rempart vitrifié » et le rapproche du « Château de verre » de ST. ALBAN-LES-EAUX ; ce texte indique en outre : « Ce type de rempart vitrifié n’est pas unique dans notre région ». A propos de l’appellation « château de verre », même remarque qu’au-dessus, voir ce qu’en dit MARKALE.

3.14.4. ST. BONNET-DES-QUARTS (région de ROANNE) : « Oppidum des Carres (ou des Quarts) ». Nous nous sommes rendus sur place en mai 1999, mais nous n’avons pu situer l’endroit de l’oppidum..

3.15. Lot (46)

3.15.1. CRAS : « Murcens ». [RALSTON (1992), p.127].

3.15.2. LUZECH : « L’impernal ». [RALSTON (1992), p. 127].

3.16. Lozère (49)

3.16.1. LA FAGE-MONTIVERNOUX : « Puy de la Fage ». [RALSTON (1992), p. 127]. Attention : confusion possible avec « Le Puy de la Fage » dans le Cantal (commune de COREN). Souvent ces sites remarquables ont été pris comme limite de plusieurs communes, ce qui peut induire des erreurs d’attribution à telle ou telle commune.

3.17. Mayenne (53)

3.17.1. LOIGNE-SUR-MAYENNE : « Les Caduries ». Vitrifié [RALSTON (1992), p. 127].

3.17.2. ST. JEAN-DE-MAYENNE : « Enceinte de Château-Meignan ». [RALSTON (1992), p. 127 ; MARCILLE (1999), p. 17].

3.17.3. STE. SUZANNE : « Le Château ». Il semble que nous ayons affaire à deux sites distincts : « Le Château » et « Le Camp des Anglais ». Selon RALSTON (1992) : « Le matériau vitrifié provenant de cette commune vient du pied du château de Ste. Suzanne et non du Camp des Anglais » .

3.18. Meurthe-et-Moselle

3.18.1. CHAMPIGNEULLES : « Enceinte de la Fourasse » (ou « Tourasse). Traces de vitrifications selon RALSTON (1992), p. 127. MARCILLE (1999).

3.18.2. ESSEY-LES-NANCY : « La butte (ou enceinte) Ste. Geneviève » (« Traces d’incendie du rempart encore observables sur le côté ouest du site », RALSTON, 1992). On ne parle pas de vitrification.

3.18.3. MESSEIN : « La Cité », ou « Le Camp d’Affrique » ou « le Vieux-Marché » (« Traces de calcination », RALSTON, 1992). On ne parle pas de vitrification.

3.18.4. SION-COUVENT : Lieu-dit non précisé. RALSTON (1992) parle de « Traces de calcination », non de vitrifications.

3.19. Morbihan

3.19.1. LANDEVANT-KERVARHET : « Kervarhet » (« Enceinte d’un diamètre de 200 m. Traces de vitrification », RALSTON, 1992).

3.20. Moselle (57)

3.20.1. LESSY : Pas de lieu dit [RALSTON (1992), p. 128].

3.21. Nièvre

3.21.1. LA MACHINE : « Enceinte du Vieux Château » ou « Cité de Barbarie ». Vitrification certaine [MARCILLE (1999), p. 18, avec un plan].

3.22. Oise

3.22.1. GOUVIEUX : Camp de César (« Traces de calcination », « Rempart massif secondaire élevé au-dessus d’un rempart à poutrage interne brûlé : ce dernier n’a pas été daté. » RALSTON (1992), p. 132. On ne parle pas de vitrification.

3.23. Orne (61)

3.23.1. ARGENTAN : Fort vitrifié. Il se peut qu’il s’agisse du même site que le suivant.

3.23.2. LA COURBE : « Le Haut du Château ». (« Traces étendues d’une combustion intense, notamment des blocs vitrifiés et des pierres de revêtement altérées par la chaleur », RALSTON, 1992).

3.24. Puy-de-Dôme (63)

3.24.1. et 3.24.2. CHATEAUNEUF-LES-BAINS : « Montagne de Villars » (« Le matériau vitrifié vient d’un rempart long de 14 m qui forme l’un des côtés d’un rectangle de 7 m X 15 m couronnant une butte de pierres », RALSTON, 1992). Une visite sur place en mai 2000 ne nous a pas permis de trouver le site mais un habitant du hameau de Villars, à qui nous avons demandé notre chemin, connaissait l’existence de « pierres fondues ». Il nous a indiqué qu’il n’y a avait pas un seul site, sur lequel on trouvait ces pierres, mais deux. D’après ses explications, nous avons compris qu’il s’agissait de deux oppida, proches l’un de l’autre.

3.25. Haut-Rhin (68)

3.25.1. HARTSMANWILLER : « H artmannswillerkopf ». « Des vestiges d’une enceinte vitrifiée d’époque protohistorique existaient au Hartmannswillerkopf mais ont été détruits durant la bataille du Vieil Armand en 1914 et 1915. » [Base Mérimée du ministère de la culture].

3.26. Haute-Saône (70)

3.26.1. BOURGUIGNON-LES-MOREY : Pas le lieu-dit. « Site de 3 ha. Traces de calcination dans un talus de pierres épais d’env. 3 mètres (On ne parle pas de vitrification) [RALSTON, 1992, p. 129].

3.26.2. MACHEZAL* : Crêt Chatelard (« Matériau vitrifié mais il n’est pas certain qu’il sot en rapport avec une vitrification » RALSTON, 1992). * Près de CHIRASIMONT, au S/E de Roanne.

Une autre source indique aussi un « tumulus burgonde et une tombe aux murs vitrifiés ». Il s’agit sans doute du même site.

3.26.3. NOROY-LES-JUSSEY : Pas de lieu-dit : « Enceinte de 2,5 ha. Traces de calcination des fortifications. » [RALSTON (1992), p. 129]. On ne parle pas de vitrification.

3. 27. Vienne (86).

3.27.1. ASLONNES : Camp d’Alaric (« Pautreau semble admettre que cette fortification a été calcinée », [RALSTON (1992)].

3.27.2. CHATEAU-LARCHER : « Site de Thors ou Thorus ». « Fort vitrifié ; les ruines n’ont pas été fouillées. »

3.27.3. QUINCAY : « Camp de Séneret (ou Céneret) » entre Quinçay et Vouillé (« Traces de calcination », [RALSTON (1992) et MARCILLE (1999)].

3.28. Haute-Vienne (87)

3.28.1. CHATEAUPONSAC : « Chégurat ou Camp de César ». Les vitrifications sont comparées à celles de White Catherhurn (Ecosse) [RALSTON (1992), pp. 89-90].

3.28.2. SEREILHAC-LA-BAISSE : Pas de lieu-dit (« Pierres vitrifiées qui ne semblent pas associées à une fortification ». [RALSTON (1992), p. 129].

3.29. Yonne (89)

3.29.1. ST. MORE : « Camp de Cora » [RALSTON (1992), p. 130].

“

“