| FRONTIERS |

Stanegate Frontier

|

The Stanegate Frontier is a suggested late first century system based on an earlier road. The Stanegate (not its Roman name) road was built c 80 AD from Carlisle to Corbridge. There were forts approximately every 22 km (Carlisle, Nether Denton, Chesterholm, Corbridge and Whickham). Around 100 AD, following the withdrawal from Scotland, the road and its forts formed the frontier of the Province. Extra forts (Old Church, Burgh-by-Sands, Carvoran and Newbrough) and fortlets were added. There may have been defences on the Cumbrian coast. See Cumbria and Northumberland for details.

Jones, G. D. B., The emergence of the Tyne – Solway frontier in Maxfield and Dobson (EDS) Roman Frontier Studies 1989, Exeter, 1991, pp98-107 |

|

Hadrian’s Wall

|

118 km long and built c 122 – 130 AD. The Wall was originally intended to be stone from Newcastle to the River Irthing and then turf to the Solway. It had mile castles every Roman mile and two turrets between each mile castle. The Wall garrison was to have been based in forts on the Stanegate. During Hadrian’s reign 12 forts were added at c 11 km intervals (Wallsend, Benwall, Rudchester, Halton Chesters, Chesters, Housesteads, Great Chesters, Birdoswold, Castlesteads, Stanwix, Burgh-by-Sands and Bowness) to house the garrison on the Wall. Later in Hadrian’s reign three further forts were added (Carrawburgh, Carvoran and Drumburgh).

The last section of turf wall was rebuilt in stone c 160 AD.

Forts and the Wall were reconstructed under Septimus Severus (early 3rd century), Constantius (early 4th century) and Theodosius (c 367 AD).

The Wall was not occupied during the Antonine advances into Scotland.

There were outpost forts at Birrens, Netherby, Bewcastle, High Rochester and Risingham and the frontier extended as a palisade, turrets and mile castles 42 km down the Cumbria coast, where there were also forts (Beckfoot, Maryport and Moresby). See Cumbria and Northumberland for details, but note that only visible turrets and milecastles have been included in the gazetteer.

Breeze & Dobson, Hadrian’s Wall, London 1991

Bellhouse, R. L., Roman Sites on the Cumberland Coast, Kendal, 1989

Collingwood Bruce, J, Handbook to the Roman Wall 13th edition, Newcastle, 1978 |

|

|

|

BRADFORD

|

Ilkley

Verbeia

SE1147 |

Flavian fort, abandoned early in the 2nd century. The 1.3 ha site was re-occupied from the late 2nd – 4th century. Garrisoned by Cohors II Lingonum equitata (late 2nd century).Frere, S. S., et al Tabula Imperii Romani – Britannia Septentrionalis, London, 1987 |

|

|

|

CUMBRIA

|

Aikton

NY3652 |

Watch tower Britannia XXVII, 1996, p405 |

Aldoth

NY1348 |

Watchtower Britannia XXIV, 1993, p286 |

Ambleside

Galava

NY3703 |

0.8 ha late Flavian fort that was enlarged under Hadrian to 1.2 ha and held, apart from during the reign of Antonine?, until 4th century. Britannia XXI, 1990, p320 |

Augill Castle

NY8014 |

Signal station? on road between Maiden Castle and Brough Britannia XX, 1989, p275 |

|

Barron’s Pike

NY5975 |

Signal station, east of Bewcastle fort. Britannia XX, 1989, p275 |

|

Beckfoot

Bibra

NY0948 |

1.1 ha Hadrianic fort held to the 4th century. Garrisoned by Cohors II Pannoniorum equitata (2nd century?). Frere, S. S. and St. Joseph, J. K., Roman Britain from the air, Cambridge, 1983, pp71-3 |

|

Beckfoot Beach

NY0846 |

Coastal mile fortlet (number 15) on Hadrian’s Wall. Bellhouse, R. L., Roman Sites on the Cumberland Coast, Kendal, 1989 |

|

Bewcastle

Fanum Cocidi?

NY5674 |

A 2.4 ha outpost fort for Hadrian’s Wall that may be on the site of an earlier fort. Garrisoned by Cohors I Aelia Dacorum milliaria? (2nd century). Britannia IX, 1978, p474 |

|

Biglands

NY2061 |

Milefortlet, part of the coastal system of Hadrian’s Wall. Bellhouse, R. L., Roman Sites on the Cumberland Coast, Kendal, 1989 |

|

Birdoswold

Banna

NY6166 |

Early 2nd century fortlet that was succeeded by a 1.6 ha Hadrian’s Wall fort. Garrisoned by Cohors I Thracum civium Romanorum (early 3rd century), Venatores Bannieuses (3rd century) and Cohors I Aelia Dacorum milliaria (3rd-4th century) Frere, S. S. and St. Joseph, J. K., Roman Britain from the air, Cambridge, 1983, pp69-71 |

|

Bleatarn

NY4661 |

Quarry for Hadrian’s Wall Collingwood Bruce, J, Handbook to the Roman Wall 13th edition, Newcastle, 1978, p43, 227, 234 |

|

Blennerhasset

NY1941 |

Fort, 3.4 ha Britannia XVIII, 1987, p12 |

|

Blitterlees

NY1052 |

Coastal mile fortlet (number 12) on Hadrian’s Wall |

|

NY1051 |

Watch tower, Hadrianic? |

|

|

Bellhouse, R. L., Roman Sites on the Cumberland Coast, Kendal, 1989 |

|

Boomby Lane

See Grinsdale |

|

|

Boothby

NY5463 |

Early 2nd century fortlet, part of the Stanegate frontier. Collingwood Bruce, J, Handbook to the Roman Wall 13th edition, Newcastle, 1978, p230 |

|

Bowness-on-Solway

Maia

NY2262 |

Hadrian’s Wall fort of 2.8 ha and held, apart from the Antonine advance into Scotland, until 4th century. Garrisoned by Cohors I Hispanorum equitata (late 4th century). Potter, T. W. J., Romans in northwest England, Kendal, 1979 |

|

Brackenrigg

NY2361 |

Two marching camps, 1.2 ha and over 3.0 ha. Welfare, H., and Swan, V., Roman Camps in England: the field archaeology, London, 1995 |

|

Brougham

Brocavum

NY5328 |

2.0 ha fort, occupied late 1st – 3rd century. Garrisoned by Numerus Equitum Stratonicianorum (3rd century). Higham, N. and Jones, B., The Carvetti, Gloucester, 1985, p64-6 |

|

NY5429 |

Marching camp, 0.5 ha. Welfare, H., and Swan, V., Roman Camps in England: the field archaeology, London, 1995 |

|

Brough under Stainmore

Verteris

NY7914 |

1.1 ha fort, occupied late 1st – 4th century. Garrisoned by Cohors VII Thracum (3rd century?) and Numerus Directorum (late 3rd century). Royal Commission on Historical Monuments England, Westmoreland, 1936, p47-8 |

|

Brownrigg

NY0538 |

Coastal fortlet on Hadrian’s Wall tower Bellhouse, R. L., Roman Sites on the Cumberland Coast, Kendal, 1989 |

|

Burgh-by-Sands

Aballava

NY3258 |

Late first century signal station. Succeeded by an early 2nd century 1.6 ha fort, possibly part of the Stanegate frontier. |

|

NY3158 |

2.1 ha fort enlarged to 3.4 ha, later than the fort above and part of the Stanegate frontier. |

|

NY3259 |

Hadrian’s Wall fort, occupied from the early 2nd – 4th century. Garrisoned by Cuneus Frisionum Aballavensium (early 3rd century), Cohors I Nervia (Nervana?) Germanorum milliaria equitata (3rd century?) and Numerus Maurorum Aurelianorum (3rd century). Milecastle 72 of Hadrian’s Wall

Frere, S. S., et al, Tabula Imperii Romani – Britannia Septentrionalis, Oxford, 1987, p13 |

|

Burrow Walls

Magis?

NY0030 |

Fort, 4th century? Garrisoned by Cohors I Aelia Classica ? or Numerus Pacensium? Cumberland and Westmoreland Antiquarian and Archaelogical Society (2nd series) LV, 1955, p30-45

|

|

Caermote

NY2036 |

1.47 ha late Flavian fort. Hadrianic or Antonine fortlet of 0.5 ha.

Cumberland and Westmoreland Antiquarian and Archaelogical Society (2nd series) LX, 1960, p20-3 |

|

Campfield

NY1960 |

Watch tower (2b) on the coastal section of Hadrian’s Wall close to Bowness on Solway. Britannia XXV, 1994, p261-263 |

|

Cardurnock

NY1758 |

Coastal mile fortlet, 0.2 ha Bellhouse, R. L., Roman Sites on the Cumberland Coast, Kendal, 1989 |

|

NY1759 |

Coastal mile fortlet Bellhouse, R. L., Roman Sites on the Cumberland Coast, Kendal, 1989 |

|

Carleton

NY4451 |

Marching camp, 0.5 ha. Welfare, H., and Swan, V., Roman Camps in England: the field archaeology, London, 1995 |

|

Carlisle

Luguvalium

NY3956 |

A timber fort built c72/3AD and demolished c103/5AD . A second timber fort was built shortly after. In turn this was replaced by a stone fort around 165 AD. A second stone fort was built in the late in the 2nd century and held until early 3rd century? Tile stamps from all the British-based legions have been found at Carlisle. Recently discovered writing tablets suggests that the earliest garison could have been Ala Gallorum Sebosiana. Hassall, see below, suggests that Legio VIIII may have been based nearby in the early 120s AD.

See also Scalesceugh

Britannia XXI, 1990, pp320-2

Britannia XXIX, 1998, pp31-84

Hassall, M., Pre-Hadrianic legionary dispositions in Roman Fortresses and their legions, ed Brewer, London & Cardiff 2000 |

|

Castle Hill

see Boothby |

|

|

Castlesteads

Camboglanna

NY5163 |

Hadrian’s Wall fort of 1.5 ha that was held until the 4th century. Garrisoned by Cohors IIII Gallorum equitata (2nd century), Cohors I Batavorum equitata (2nd century?) and Cohors II Tungrorum milliaria equitata civium latinorum (3rd century). Collingwood Bruce, J, Handbook to the Roman Wall 13th edition, Newcastle, 1978, p228-9 |

|

Castrigg

NY6722 |

Watch tower on road between Maiden Castle and Brough Journal of Roman Studies XXXXI, p53 |

|

Coombe Crag

NY5965 |

Quarry for Hadrian’s Wall Collingwood Bruce, J, Handbook to the Roman Wall 13th edition, Newcastle, 1978, p43, 218 |

|

Crackenthorpe

NY6523 |

Marching camp, 9.3 h, Flavian? Welfare, H., and Swan, V., Roman Camps in England: the field archaeology, London, 1995 |

|

Dalston

NY3853 |

Fort, 2.4-3.2 ha Britannia XXVII, 1996, p405 |

|

Drumburgh

Concavata

NY2659 |

0.8 ha Hadrian’s Wall fort that was replaced circa 160 AD by a smaller fort with a stone wall. Garrisoned by Cohors II Lingonum equitata (4th century). Collingwood Bruce, J, Handbook to the Roman Wall 13th edition, Newcastle, 1978, p250-1 |

|

Dubmill Point

NY0745 |

Coastal mile fortlet, number 17, on Hadrian’s Wall. Bellhouse, R. L., Roman Sites on the Cumberland Coast, Kendal, 1989 |

|

East Cote

NY1155 |

Fortlet Bellhouse, R. L., Roman Sites on the Cumberland Coast, Kendal, 1989 |

|

Farnhill

NY3057 |

Watchtower Britannia XXVI, 1995, pp342-3 |

|

Finglandrigg

NY2657 |

Fort, 1.6 ha, part of the western Staingate system? Watchtower

Britannia XVIII, 1987, p13 |

|

Galley Gill

See Old Penrith |

|

|

Gelt

NY5258 |

Quarry for Hadrian’s Wall |

|

NY5357 |

Quarry for Hadrian’s Wall Collingwood Bruce, J, Handbook to the Roman Wall 13th edition, Newcastle, 1978, p42, 227 |

|

Gillalees

see Robin Hood’s Butt |

|

|

Golden Fleece

See Carleton |

|

|

Grey Havens

NY2362 |

Marching camp, 0.6 ha. Welfare, H., and Swan, V., Roman Camps in England: the field archaeology, London, 1995 |

|

Grinsdale

NY3657 |

Four marching camps, 0.5 ha, 0.2 ha, 2.3 ha and 1.2 ha Welfare, H., and Swan, V., Roman Camps in England: the field archaeology, London, 1995 |

|

Hardknott

Mediobogdum

NY2101 |

2nd century fort, 1.3 ha that was unoccupied during the Antonine occupation of Scotland. Rebuilt circa 165 AD? Garrisoned by Cohors IIII Delmatarum (early 2nd century?). Garlick, T., Hardknott Castle Roman Fort, Lancaster, 1985 |

|

Heather Bank

see Low Mire |

|

|

Herd Hill

NY1759 |

Coastal mile fortlet, number 4, on Hadrian’s Wall Bellhouse, R. L., Roman Sites on the Cumberland Coast, Kendal, 1989 |

|

High Crosby

NY4559

|

Fortlet? on the Stanegate frontier. Britannia XVII, 1986, p383 |

|

NY4560 |

Two marching camps, 1.0 ha and 9.7 ha Welfare, H., and Swan, V., Roman Camps in England: the field archaeology, London, 1995 |

|

Johnson’s Plain

NY8414 |

Signal station on road between Maiden Castle and Brough. Britannia XXII, 1991, p235-7 |

|

Kirkandrews

NY3458 |

Watch tower Britannia XXVII (1996) p406 |

|

Kirkbampton

NY2657 |

Watch tower Britannia XXVII (1996) p406 |

|

Kirkbride

Briga?

NY2357 |

3 ha Trajanic fort. Part of the Stanegate frontier occupied till circa 120 AD. Transactions of the Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society 2nd series LXXXII, 1982, Carlisle, pp35-50 |

|

Kirkby Thore

Bravoniacum

NY6325 |

Flavian fort site, re-occupied early in the 3rd century and maintained until the 4th. Garrisoned by Numerus militum Syrorum sagittariorum (3rd century) and Numerus Defensorum (late 3rd century). Journal of Roman Studies XLVIII, 1958,

pp86-7 |

|

NY6225 |

Three marching camps, 4.8 ha, 1.7 ha and 1.2 ha Welfare, H., and Swan, V., Roman Camps in England: the field archaeology, London, 1995 |

|

Knockcross

See Grey Havens |

|

|

Knowe Farm

See Old Penrith |

|

|

Langwathby Moor

NY5733 |

Marching camp Welfare, H., and Swan, V., Roman Camps in England: the field archaeology, London, 1995 |

|

Low Borrowbridge

NY6001 |

Flavian fort that was succeeded by Hadrianic fort with stone wall 1.1 ha and occupied until the 4th century. Shotter, D., Romans and Britains in North-West England, Lancaster, 1993

|

|

Low Mire

NY0741 |

Coastal mile fortlet, number 20, on Hadrian’s Wall. Bellhouse, R. L., Roman Sites on the Cumberland Coast, Kendal, 1989 |

|

Maiden Castle

NY8713 |

0.2 ha, fortlet, occupied from the late 2nd to the 4th century. Farrar, R. A. H., in Hanson and Keppie, Roman Frontier Studies 1979, Oxford 1980, pp220-1 |

|

Mains Rigg

NY6165 |

Stone signal station between Nether Denton and Throp. Part of the Stanegate frontier. Collingwood Bruce, J, Handbook to the Roman Wall 13th edition, Newcastle, 1978, p208-9 |

|

Maryport

Alauna

NY0337 |

Fort (occupied from the early 2nd – 4th century) that was part of the coastal system of Hadrian’s Wall. Garrisoned by Cohors I Aelia Hispanorum milliaria equitata (early 2nd century century), Cohors I Delmatarum equitata (mid 2nd century), Cohors I Baetasiorum civium Romanorum ob virtutem et fidem (late 2nd century) and Cohors II Nerviorum (4th century). Jarrett, M. G., Maryport, Cumbria: A Roman fort and its garrison, Kendall, 1976 |

|

Mawbray

NY0847 |

Coastal fortlet on Hadrian’s Wall Bellhouse, R. L., Roman Sites on the Cumberland Coast, Kendal, 1989 |

|

Moresby

Gabrosentum?

NX9821 |

Fort, 1.5 ha occupied from the late Hadrianic – 4th century. Garrisoned by Cohors II Lingonum equitata (2nd century) and Cohors II Thracum equitata (3rd-4th century). Collingwood Bruce, J, Handbook to the Roman Wall 13th edition, Newcastle, 1978, p281-3 |

|

Moss Side

See High Crosby |

|

|

Netherby

Castra Exploratum

NY3971 |

Outpost fort for Hadrian’s Wall. Abandoned before Bewcastle and the eastern outposts. Garrisoned by Cohors I Nervia (or Nervana) Germanorum milliaria equitata (3rd century?), Cohors I Aelia Hispanorum milliaria equitata (3rd century) and Numerus Exploratorum (early – mid 4th century). Collingwood Bruce, J, Handbook to the Roman Wall 13th edition, Newcastle, 1978, p311-4 |

|

Nether Denton

NY5964 |

Flavian fort, 2.8 ha, reduced to 1.8 ha and rebuilt in stone under Trajan? when it may have formed part of the Stanegate frontier. Replaced by a fortlet under Hadrian? Jones, G. D. B., The emergence of the Tyne-Solway frontier in Maxfield and Dobson (eds) Roman Frontier Studies 1989, Exeter, 1991, pp98-107 |

|

Nowtler Hill

See Grinsdale |

|

|

Old Carlisle

Maglona

NY2646 |

Fort of 1.8 ha. Garrisoned by Ala Augusta Gallorum Proculeiana(late 2nd – mid 3rd century) and ?Numerus Solensium (late 4th century). Ala Augusta ob virtutem appellata which is also recorded here may be a synonym for Ala Augusta Gallorum as the fort was only large enough for one quingenary unit. Higham, N. and Jones, B., The Carvetii, Gloucester, 1985, pp60-2 |

|

Old Church

NY5162 |

1.5 ha fort Trajanic? on the Stanegate frontier? Collingwood Bruce, J, Handbook to the Roman Wall 13th edition, Newcastle, 1978, pp230-2 |

|

Old Penrith

Voreda

NY4938 |

Late 1st century fort that was unoccupied circa 120 – 160 AD?, but then held until the late 4th century. Garrisoned by Cohors II Gallorum equitata (3rd century), ?Vexillatio Voredensium (3rd century) and ?Vexillatio Marsacorum (3rd century). Higham, N. and Jones, B., The Carvetii, Gloucester, 1985

Marching camp 1.6 ha (Galley Gill)

Welfare, H., and Swan, V., Roman Camps in England: the field archaeology, London, 1995 |

|

NY4839 |

Marching camp, 1.6 ha (Knowe Farm) Welfare, H., and Swan, V., Roman Camps in England: the field archaeology, London, 1995 |

|

Papcastle

Derventio

NY1031 |

Late 1st or early 2nd century fort. It had a stone wall added in 2nd century and was held until 3rd century. A late 4th century fort of 2.8 ha was built on same site. Garrisoned by Cuneus Frisionum Aballavensium (mid 3rd century). Transactions of the Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society 2nd series LXV, 1965, Carlisle, pp102-14 |

|

Pasture House

NY1860 |

Coastal mile fortlet on Hadrian’s Wall Bellhouse, R. L., Roman Sites on the Cumberland Coast, Kendal, 1989 |

|

Plumpton Head

NY4935 |

Marching camp 9.5 ha, Flavian? the camp is an irregular shape and includes a incurved section to avoid boggy ground. Welfare, H., and Swan, V., Roman Camps in England: the field archaeology, London, 1995 |

|

Punch Bowl

NY8214 |

Signal station on road between Maiden Castle and Brough. Britannia VII, 1976, p312 |

|

Raise Howe

see Aldoth |

|

|

Ravenglass

Glannoventa

SD0895 |

Hadrianic fortlet succeeded by a Hadrianic fort of 1.5 ha. This was rebuilt early 2nd century. Rebuilt again late 4th century and held until beginning of the 5th century. Garrisoned by Cohors I Morinorum et Cersiacorum (4th century) Potter, T. W. J., Romans in northwest England, Kendall, 1979 |

|

Risehow

NY0234 |

Coastal mile fortlet on Hadrian’s Wall. Bellhouse, R. L., Roman Sites on the Cumberland Coast, Kendal, 1989 |

|

Robin Hood’s Butt

NY5771 |

Signal station close to Bewcastle fort. Southern, P., Signals versus Illumination on Roman frontiers, Britannia XXI, 1990, p233 |

|

Sandford

See Warcop |

|

|

Scalesceugh

NY4449 |

Tile works and pottery of late 1st – early 2nd century date. Operated by Legio IX Hispana. Bellhouse, R. L., Roman tileries at Scalesceugh and Brampton, Transactions of the Cumberland and Westmoreland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society (2nd series) 71, pp35-44 |

|

Silloth

see Beckfoot |

|

|

Skinburness

NY1356 |

Coastal mile fortlet on Hadrian’s Wall Bellhouse, R. L., Roman Sites on the Cumberland Coast, Kendal, 1989 |

|

Stanwix

Uxelodunum

NY4057 |

4.0 ha fort on Hadrian’s Wall that was held until the 4th century. Garrisoned by Ala Augusta Gallorum Petriana milliaria civium Romanorum bis torquata (2nd – 4th century), the only milliaria ala in the British garrison and the most powerful unit on the wall. Collingwood Bruce, J, Handbook to the Roman Wall 13th edition, Newcastle, 1978, pp236-9 |

|

Steadfolds

See Watchclose |

|

|

Swarthy Hill

NY0640 |

Coastal mile fortlet, number 21, on Hadrian’s Wall occupied in the first half of 2nd century. Bellhouse, R. L., Roman Sites on the Cumberland Coast, Kendal, 1989 |

|

Troutbeck

NY3827 |

1.5 ha fort and 0.7 ha fortlet. Frere, S. S. and St Joseph, J. K., Roman Britain from the air, Cambridge, 1983

Two marching camps, 9.7 ha Flavian? and 0.6 ha |

|

NY3727 |

Marching camp 4.0 ha Welfare, H., and Swan, V., Roman Camps in England: the field archaeology, London, 1995 |

|

Upper Denton

See Mains Rigg |

|

|

Warcop

NY7416 |

Marching camp Welfare, H., and Swan, V., Roman Camps in England: the field archaeology, London, 1995 |

|

Watchclose

NY4760 |

Marching camp, 0.5 ha Welfare, H., and Swan, V., Roman Camps in England: the field archaeology, London, 1995 |

|

Watchcross

See Watchclose |

|

|

Watercrook

Alauna

SD5190 |

1.5 ha Flavian fort; held until mid – 2nd century and until 4th century? Potter, T. W. J., The Romans in northwest England, Kendal, 1979 |

|

Wetheral

NY4653 |

Quarry (Triassic sandstone) for Hadrian’s Wall Johnson, G. A. L., Geology of Hadrian’s Wall: Geologists’ Association Guide 59, London, 1997 |

|

Willowford

NY6266 |

Bridge carrying Hadrian’s Wall over the river Irthing Marching camp, 0.8 ha

Welfare, H., and Swan, V., Roman Camps in England: the field archaeology, London, 1995 |

|

Wolsty North

NY0950 |

Watch tower on the coastal section of Hadrian’s Wall. Bellhouse, R. L., Roman Sites on the Cumberland Coast, Kendal, 1989 |

|

Wolsty South

NY0950 |

Watch tower on the coastal section of Hadrian’s Wall. Bellhouse, R. L., Roman Sites on the Cumberland Coast, Kendal, 1989 |

|

Wreay

NY4449 |

1.3 ha fort Transactions of the Cumberland and Westmoreland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society (2nd series) LIV, 1954, pp9-16 |

|

NY4448 |

Fortlet or signal tower, 4th century? Marching camp, 0.4 ha

Farrar, R. A. H., in Hanson, W. S. and Keppie, L. J. F., (eds) Roman Frontier Studies, Oxford, 1971, pp213-5 |

|

|

|

DARLINGTON

|

Piercebridge

Morbium?

NZ2115 |

4.6 ha fort of late 3rd – 4th century date. Garrisoned by Equites Catafractarii? (4th century). Although the fort was built about 260 AD the vicus is older, but no sign has yet been found of an earlier, Flavian?, fort. Britannia XIV, 1983, pp292-3 |

|

|

|

DONCASTER

|

Burghwallis

SE5112 |

Three forts of late 1st – 2nd century date.Frere, S. S., et al Tabula Imperii Romani – Britannia Septentrionalis, London, 1987 |

|

Doncaster

Danum

SE5703 |

A Flavian fort (2.6 ha) abandoned circa 120 AD.Followed by a 2.4 ha fort, built mid 2nd century.

The final fort, 2.4 ha, dates from the late 3rd – 4th century. Garrisoned by Equites Crispiani (late 4th century).

Buckland, P. C., Roman South Yorkshire: a source book, Sheffield, 1986 |

|

Rossington

SK6399 |

Small fortress (9.3 ha), Flavian or earlier.Buckland, P. C., Roman South Yorkshire: a source book, Sheffield, 1986 |

|

|

|

DURHAM

|

Binchester

Vinovium

NZ2131 |

3.8 ha Flavian fort that was occupied apart from part of the 2nd century till the 4th. Garrisoned by Ala Hispanorum Vettonum civium Romanorum (late 2nd – early 3rd century?) and Cuneus Frisiorum Vinoviensium (3rd century). Hanson and Keppie, Roman Frontier Studies 1979, Oxford 1980, pp233-54 |

Bowes

Lavatris

NY9913 |

Flavian fort, 1.7 ha. The site was occupied again from mid 2nd until the 4th century. Garrisoned by Cohors IIII Breucorum (2nd century), Cohors I Thracum equitata (3rd century) and Numerus Exploratum (late 4th century). Journal of Roman Studies LVIII, 1968, pp179-81 |

Bowes Moor

NY9212 |

Signal station, occupied late 3rd – 4th century. Farrar, R. A. H., in Hanson and Keppie, Roman Frontier Studies 1979, Oxford 1980, pp220-3

Small marching camp, contemporary with the signal station?

Welfare, H., and Swan, V., Roman Camps in England: the field archaeology, London, 1995 |

|

Chester-le-Street

Concangis

NZ2751 |

Mid to late 2nd century timber fort that was succeeded by a stone fort during the 3rd century and occupied until the 4th. Garrisoned by Numerus Concangiensium? (3rd century?) and Numerus Vigilum (4th century?). Bishop Archaeologia Aeliana XXI, 1993, pp29-85 |

|

Ebchester

Vindomora

NZ1055 |

Flavian fort of 1.6 ha that was occupied until the 4th century, but with a gap in occupation from circa 140-160AD. Garrisoned by Cohors IIII Breucorum (3rd century). Archaeologia Aeliana XLII, 1964, pp179-80 |

|

Greta Bridge

Morbium?

NZ0813 |

Antonine (?) fort that was occupied until the 4th century. Britannia XXIX, 1998, pp111-184 |

|

Lanchester

Longovicium

NZ1546 |

Fort, 2.5 ha that was occupied from the late 2nd century and again from mid 3rd – 4th century. Garrisoned by Cohors I fida Vardullorum milliaria equitata civium Romanorum (late 2nd century), Cohors I Lingonum equitata (3rd century), Vexillatio Sueborum Longovcianorum (mid 3rd century) and Numerus Longovicianorum. Journal of Roman Studies XXVIII, 1938, pp177-8 (plan, plate xvii) |

|

Rey Cross

NY9012 |

8.1 ha marching camp, Flavian? with 11 titulu. Large enough to have accomodated a legion with auxiliaries. Welfare, H., and Swan, V., Roman Camps in England: the field archaeology, London, 1995 |

|

Roper Castle

NY8811 |

Signal station. Farrar, R. A. H., in Hanson and Keppie, Roman Frontier Studies 1979, Oxford 1980, pp220-2 |

|

Sandforth Moor

NZ2021 |

Marching camp, 0.8 ha. Welfare, H., and Swan, V., Roman Camps in England: the field archaeology, London, 1995 |

|

Scargill Moor

NY9910 |

Shrines and altar associated with the fort at Bowes. |

|

Vale House

NY9412 |

Signal station? Farrar, R. A. H., in Hanson and Keppie, Roman Frontier Studies 1979, Oxford 1980, pp224-5 |

|

|

|

GATESHEAD

|

Whickham

NZ2160 |

Flavian earth and timber fort with several occupation periods.Frere, S. S., et al Tabula Imperii Romani – Britannia Septentrionalis, London, 1987 |

|

Washing Well

See Whickham |

|

|

|

|

KIRKLEES

|

Grimescar

SE1319 |

Tile kilns operated by Cohors IIII Breucorum. Tiles made here found at Slack and Castleshaw.Frere, S. S., et al Tabula Imperii Romani – Britannia Septentrionalis, London, 1987 |

|

Slack

Camulodunum

SE0817 |

Flavian fort, 1.5 ha, abandoned circa 140 AD. Garrisoned by Cohors IIII Breucorum (early 2nd?).Frere, S. S., et al Tabula Imperii Romani – Britannia Septentrionalis, London, 1987 |

|

|

|

LANCASHIRE

|

Castlehows

See Low Burrow Bridge |

|

Burrow in Lonsdale

Calacum

SD6175 |

1.9 ha fort, occupied from the Flavian period until – early 2nd century. In the 3rd century a stone fort was built and occupied until mid 4th century. Shotter, D. and White, A., The Romans in Lunesdale, Lancaster 1995 |

|

Kirkham

SD4332 |

Flavian fort that was abandoned early in the 2nd century. Shotter, D., Romans and Britons in North-West England, Lancaster 1993 |

|

Lancaster

SD4761 |

Flavian fort that received a stone wall in the Trajanic period. The site was unoccupied from the mid 2nd – 3rd century? A stone fort of typical late design was built during the 4th century. Garrisoned by Ala Augusta Gallorum Proculeiana, (late 1st), Ala Gallorum Sebosiana (3rd century) and Numerus Barcariorum (4th century). Shotter, D. and White, A., The Romans in Lunesdale, Lancaster 1995 |

|

Low Burrow Bridge

NY6001 |

Fort founded in the Flavian period that may have been reconstructed in the late 1st or early 2nd century. The site was occupied until the late 4th century. Shotter, D. and White, A., The Romans in Lunesdale, Lancaster 1995 |

|

Overburrow

See Burrow in Lonsdale |

|

|

Ribchester

Bremetenacum Veteranorum

SD6434 |

Early Flavian fort that was succeeded by a 2.7 ha timber late Flavian fort. This was in turn succeeded by a stone fort early in the 2nd century that remained in use into the 4th century. Garrisoned by Ala II Asturum (late 1st-2nd century?), Numerus equitatum Sarmatarum (2nd-3rd century?) and Cuneus Sarmatarum (3rd-4th century). Shotter, D. Romans and Britons in North-West England, Lancaster 1993 |

|

Walton-le-Dale

SD5528 |

Supply base and industrial site from the late 1st century into the early 2nd century. Shotter, D. Romans and Britons in North-West England, Lancaster 1993, p21 |

|

|

|

LEEDS

|

Adel

SE2741 |

Fort?Frere, S. S., et al Tabula Imperii Romani – Britannia Septentrionalis, London, 1987 |

|

|

|

NORTH LINCOLNSHIRE

|

Kirmington

TA0511 |

3.4 ha fort Britannia VIII, 1977, pp189-91 |

|

|

|

MANCHESTER

|

Manchester

Mamucium

SJ8397 |

1.6 ha Flavian fort. The site was re-occupied from late 2nd – 4th century. Garrisoned by Cohors III Bracaraugustanorum (early 2nd?), and Cohors I Frisiavonum (early 2nd?). Shotter, D. Romans and Britons in North-West England, Lancaster 1993 |

|

|

|

NEWCASTLE UPON TYNE

|

Benwall

Condercum

NZ2164 |

Hadrian’s Wall fort (2.3 ha). Garrisoned by Cohors I Vangionum milliaria equitata (late 2nd century) and Ala I Hispanorum Asturum (late 2nd – 4th).Frere, S. S., et al Tabula Imperii Romani – Britannia Septentrionalis, London, 1987 |

|

Newcastle upon Tyne

Pons Aelius

NZ2563 |

Fort of unknown size guarding the bridge over the Tyne, may have predated Hadrian’s Wall. Garrisoned by Cohors I Thracum equitata (2nd century?), Cohors I Ulpia Traiana Cugernorum civium Romanorum (early 3rd century) and Cohors I Cornoviorum (4th century).Frere, S. S., et al Tabula Imperii Romani – Britannia Septentrionalis, London, 1987 |

|

East Denton

NZ1965 |

Hadrian’s Wall turret (no 7b).Breeze & Dobson, Hadrian’s Wall, London 1991 |

|

|

|

NORTHUMBERLAND

|

Barcombe

NY7765

|

Watch tower? |

| NY7866 |

Watch tower. Quarry (Carboniferous sandstone) for Hadrian’s Wall.

Johnson, G. A. L., Geology of Hadrian’s Wall: Geologists’ Association Guide 59, London, 1997 |

Bagraw

NY8496 |

Marching camp with annex or two camps, 7.7 ha in total. Welfare, H., and Swan, V., Roman Camps in England: the field archaeology, London, 1995 |

Bean Burn

See Seatsides |

|

|

Bellshiel

NY8199 |

16.0 ha marching camp, Flavian? Welfare, H., and Swan, V., Roman Camps in England: the field archaeology, London, 1995 |

|

Birdhope

NY8298 |

Three marching camps, 12.3 ha Flavian?, 3.1 ha and 2.1 ha. Welfare, H., and Swan, V., Roman Camps in England: the field archaeology, London, 1995 |

|

Bishop Rigg

see Corbridge – Red House |

|

|

Blakehope

NY8594 |

Marching camp? 6.2 ha, succeeded? by 1.5 ha fort. |

|

Brown Dikes

NY8370 |

Marching camp, 0.4 ha. Welfare, H., and Swan, V., Roman Camps in England: the field archaeology, London, 1995 |

|

Burnhead

NY7066 |

Marching camp, 3.5 ha. Welfare, H., and Swan, V., Roman Camps in England: the field archaeology, London, 1995 |

|

Carham

NT7937 |

Marching camp? Welfare, H., and Swan, V., Roman Camps in England: the field archaeology, London, 1995 |

|

Carrawburgh

Brocolitia

NY8571 |

Hadrian’s Wall fort, 1.5 ha. Garrisoned by Cohors I Aquitanorum equitata (early 2nd century), Cohors II Nerviorum civium Romanorum (2nd century?), Cohors I Ulpia Traiana Cugernorum civium Romanorum (late 2nd century?) and Cohors I Batavorum equitata (3rd-4th century). Mithreum

Frere, S. S., et al, Tabula Imperii Romani – Britannia Septentrionalis, Oxford, 1987

|

|

Carvoran

Magnis

NY6665 |

Stanegate frontier fort that was succeeded by a Hadrian’s Wall fort (1.5 ha) and held until 4th century. Garrisoned by Cohors I Hamiorum sagittariorum (early 2nd century, late 2nd century), Cohors I Batavorum equitata (2nd century?) and Cohors II Delmatarum equitata (3rd-4th century).Frere, S. S., et al, Tabula Imperii Romani – Britannia Septentrionalis, Oxford, 1987 |

|

Cawfields

NY7166 |

Hadrian’s Wall milecastle, early 2nd century. Marching camp, 0.6 ha. See also Chesters Pike and Burnhead temporary camps.

Welfare, H., and Swan, V., Roman Camps in England: the field archaeology, London, 1995

|

|

Chapel Rigg

NY6465 |

Marching camp, 0.6 ha. Welfare, H., and Swan, V., Roman Camps in England: the field archaeology, London, 1995 |

|

Chesterholm

Vindolanda

NY7766 |

Timber fort, 1.4 ha, built late 80s AD and garrisoned by elements of Cohors I Tungrorum, which may have been enlarged to a milliaria cohort during this period. This fort was followed by another timber fort built late 80s early 90s AD and garrisoned by Cohors VIIII Batavorum. A third timber fort, 3.2 ha, was built circa 95-105 AD and garrisoned by Cohors VIIII Batavorum now milliaria equitata with elements of Cohors III Batavorum milliaria equitata (the Batavians were replaced by Cohors I Tungrorum milliaria circa 105 AD – mid 2nd century). Also present in the early 120s AD were the cavalry element of Cohors I fida Vardullorum equitata civium Romanorum and possibly legionaries.

This fort was replaced by a stone one, 1.6 ha, built circa 120 AD. Cohors II Nerviorum civium Romanorum is recorded here during the 2nd century but may not have been the garrison.

A second stone fort, 1.4 ha, was built circa 230 AD and garrisoned by Cohors IIII Gallorum equitata (3rd-4th century).

Frere, S. S., et al Tabula Imperii Romani – Britannia Septentrionalis, London, 1987

NB. The continuing work at Chesterholm makes providing a reference that easily expands this gazetteer entry difficult. |

|

Chesters

Cilurnum

NY9170 |

Hadrian’s Wall fort (2.3 ha) garrisoned by Ala Augusta ob virtutem appellata (early 2nd), Cohors I Vangionum milliaria equitata (late 2nd century?), Cohors I Delmatarum equitata (late 2nd?) and Ala II Austurum (late 2nd – 4th).Frere, S. S., et al Tabula Imperii Romani – Britannia Septentrionalis, London, 1987 |

|

Chesters Pike

NY7067 |

Marching camp, 0.5 ha. Welfare, H., and Swan, V., Roman Camps in England: the field archaeology, London, 1995 |

|

Chew Green

NT7808 |

Two marching camps, fort and two? fortlets, on Dere Street as it climbs over the Cheviots. The chronology is unclear, a possible sequence is marching camp 7.7 ha, fortlet? 0.3 ha? Flavian?, fort 2.6 ha Flavian?, marching camp 5.5 ha, fortlet 0.4 ha Antonine? Frere, S., S., and St Joseph, J., K., Roman Britain from the air, Cambridge, 1983 |

|

Coesike

NY8170 |

Three marching camps, 0.2 ha, 0.1 ha? and 0.2 ha. Welfare, H., and Swan, V., Roman Camps in England: the field archaeology, London, 1995 |

|

Corbridge

Coria? Corstopitum?

NY9864 |

Fort built circa 90 AD and occupied until the mid 2nd century. The garrison may have included elements of Cohors I Tungrorum. A late 1st century gravestone of a trooper of Ala Augusta Gallorum Petriana milliaria civium Romanorum bis torquata was found at Corbridge;. The fort was succeeded by an industrial complex, mid 2nd – early 3rd century, manned by vexilations of Legio VI Victrix and Legio II Augusta.

Gillam Archaeologia Aeliana (1977) pp47-74 |

|

Corbridge – Red House

NY9765 |

Flavian vexillation fortress? The base for Agricola’s advance into Scotland? Garrisoned by Legio VIIII Hispana? |

|

NY9665 |

Marching camp,1.0 ha; later than the fortress. Welfare, H., and Swan, V., Roman Camps in England: the field archaeology, London, 1995 |

|

Crooks

NY6365 |

Marching camp, 0.9 ha. Welfare, H., and Swan, V., Roman Camps in England: the field archaeology, London, 1995 |

|

Dargues

NY8693 |

Marching camp, 5.9 ha Flavian? Welfare, H., and Swan, V., Roman Camps in England: the field archaeology, London, 1995 |

|

East Learmouth

NT8736 |

Marching camp, 13.6 ha Welfare, H., and Swan, V., Roman Camps in England: the field archaeology, London, 1995 |

|

Fallowfield Fell

NY9368 |

Quarry (Upper Carboniferous sandstone) for Hadrian’s Wall. Johnson, G. A. L., Geology of Hadrian’s Wall: Geologists’ Association Guide 59, London, 1997 |

|

Farnley

NY9963 |

Three marching camps, one 1.6 ha the other two of unknown size. Welfare, H., and Swan, V., Roman Camps in England: the field archaeology, London, 1995 |

|

Featherwood East

NT8205 |

Marching camp, 15.9 ha. Welfare, H., and Swan, V., Roman Camps in England: the field archaeology, London, 1995 |

|

Featherwood West

NT8105 |

Marching camp, 15.6 ha. Welfare, H., and Swan, V., Roman Camps in England: the field archaeology, London, 1995 |

|

Fell End

NY6865 |

Marching camp, 8.7 ha. Welfare, H., and Swan, V., Roman Camps in England: the field archaeology, London, 1995 |

|

Four Laws

NY9082 |

Two marching camps , 2.4 ha and 0.3 ha Welfare, H., and Swan, V., Roman Camps in England: the field archaeology, London, 1995 |

|

Glenwhelt Leazes

NY6565 |

Marching camp, 1.2 ha. Welfare, H., and Swan, V., Roman Camps in England: the field archaeology, London, 1995 |

|

Great Chesters

Aesica

NY7066

|

Hadrian’s Wall fort, 1.4 ha. Garrisoned by Cohors VI Nerviorum (early 2nd century), Cohors VI Raetorum (mid 2nd century), Cohors II Asturum equitata (3rd century), Vexillatio Gaesatorum Raetorum (3rd century) and Cohors I Asturum equitata (4th century). See Burnhead, Cawfields and Chesters Pike for marching camps.

Frere, S. S., et al Tabula Imperii Romani – Britannia Septentrionalis, London, 1987 |

|

Greenlee Lough

NY7769 |

Marching camp, 1.4 ha. Welfare, H., and Swan, V., Roman Camps in England: the field archaeology, London, 1995

Quarry (Lower Carboniferous sandstone) for Hadrian’s Wall

Johnson, G. A. L., Geology of Hadrian’s Wall: Geologists’ Association Guide 59, London, 1997 |

|

Grindon Hill

NY8267 |

Marching camp, 0.1 h. Welfare, H., and Swan, V., Roman Camps in England: the field archaeology, London, 1995 |

|

Grindon School

NY8169 |

Very small marching camp. Welfare, H., and Swan, V., Roman Camps in England: the field archaeology, London, 1995 |

|

Halton Chesters

Onnum

NY9968 |

Hadrian’s Wall fort, 1.7 ha that was enlarged to 1.9 ha in the 3rd century. Garrisoned by Ala I Pannoniorum Sabiniana (3rd – 4th century). Frere, S. S., et al Tabula Imperii Romani – Britannia Septentrionalis, London, 1987 |

|

Haltwhistle

NY6965 |

Two marching camps, 0.4 ha and 0.6 ha. |

|

NY7065 |

Very small marching camp. Welfare, H., and Swan, V., Roman Camps in England: the field archaeology, London, 1995 |

|

Haltwhistle Burn

NY7166 |

Trajanic fortlet, 0.3 ha. Part of the Stanegate frontier Four temporary camps, 1.0 ha, 0.7 ha, 0.3 ha and the fourth tiny.

Welfare, H., and Swan, V., Roman Camps in England: the field archaeology, London, 1995

Quarry for Hadrian’s Wall |

|

Haltwhistle Common

See Markham Cottage |

|

|

High Rochester

Bremenium

NY8398 |

2 ha Flavian fort that was rebuilt as an outpost fort for Hadrian’s Wall in the mid 2nd century and held until mid 4th century. Garrisoned by Cohors I Linngonum equitata (mid 2nd century), Cohors I Aelia Dacorum milliaria (late 2nd century?) and Cohors I Delmatarum equitata (late 2nd century?). Several marching camps, see Birdhope, Sills Burn, Silloans and Bellshiel

Frere, S. S., et al Tabula Imperii Romani – Britannia Septentrionalis, London, 1987 |

|

Horsley

See Bagraw |

|

|

Housesteads

Vercovicium

NY7968 |

Hadrian’s Wall fort of 2.1 ha. Garrisoned by Cohors I Tungrorum milliaria (3rd century), Cuneus Frisiorum Vercoviciensium (early 3rd century) and Numerus Hnaudifridi (3rd century).Frere, S. S., et al Tabula Imperii Romani – Britannia Septentrionalis, London, 1987 |

|

Lady Shield

See Grindon Hill and Grindon School |

|

|

Learchild

Alauna

NU1011 |

Flavian fort, enlarged in the 2nd centuryFrere, S. S., et al Tabula Imperii Romani – Britannia Septentrionalis, London, 1987 |

|

Learmouth

See East Learmouth |

|

|

Lees Hall

NY7065 |

Temporary camp with an outerwork or a fort with internal clavicula, 4.2 ha. Welfare, H., and Swan, V., Roman Camps in England: the field archaeology, London, 1995 |

|

Limestone Corner

NY8771 |

Marching camp, 0.2 ha. Welfare, H., and Swan, V., Roman Camps in England: the field archaeology, London, 1995 |

|

Longshaws

NZ1388 |

Fortlets?Frere, S. S., et al Tabula Imperii Romani – Britannia Septentrionalis, London, 1987 |

|

Markham Cottage

NY7066 |

Two marching camps 16.8 ha and 3.4 ha. Welfare, H., and Swan, V., Roman Camps in England: the field archaeology, London, 1995 |

|

Milestone House

NY7266 |

Unusually long and thin marching camp, 7 ha. Welfare, H., and Swan, V., Roman Camps in England: the field archaeology, London, 1995 |

|

Mindrum

NT8433 |

Marching camp. Welfare, H., and Swan, V., Roman Camps in England: the field archaeology, London, 1995 |

|

Newbrough

NY8668 |

4th century fortlet, 0.3 ha. |

|

NY8767 |

Fort, part of the Stanegate frontier? Frere, S. S., et al Tabula Imperii Romani – Britannia Septentrionalis, London, 1987 |

|

Norham

NT8845 |

Marching camp, 0.5 ha. Welfare, H., and Swan, V., Roman Camps in England: the field archaeology, London, 1995 |

|

North Yardhope

See Yardhope |

|

|

Peasteel Crags

See Fell End |

|

|

Queen’s Crags

NY7970 |

Quarry (Lower Carboniferous sandstone) for Hadrian’s Wall Johnson, G. A. L., Geology of Hadrian’s Wall: Geologists’ Association Guide 59, London, 1997 |

|

Risingham

Habitancum

NY8986 |

An outpost fort, 1.8 ha, for Hadrian’s Wall built mid 2nd century and unoccupied in the late 2nd century. It was rebuilt early 3rd century and occupied until the mid 4th century. Garrisoned by Cohors IIII Gallorum equitata (late 2nd century), Cohors I Vangionum milliaria equitata (3rd century) and Numerus Exploratorum habitancensium (3rd-4th century), Vexillatio Raetorum Gaesa.

Frere, S. S., et al Tabula Imperii Romani – Britannia Septentrionalis, London, 1987

|

|

Rudchester

Vindobala

NZ1167 |

Hadrian’s Wall fort that was rebuilt early 3rd century and at least partly unoccupied during late 3rd century. Held until the 4th century. Garrisoned by Cohors I Frisiavonum (Frixagorum) (3rd-4th century).Frere, S. S., et al Tabula Imperii Romani – Britannia Septentrionalis, London, 1987 |

|

Seatsides

NY7566 |

Four marching and practice camps?, 6.7 ha, 3.4 ha, 0.3 ha and 0.04ha. Welfare, H., and Swan, V., Roman Camps in England: the field archaeology, London, 1995 |

|

Silloans

NT8200 |

Marching camp, 18.4 ha, Flavian? Welfare, H., and Swan, V., Roman Camps in England: the field archaeology, London, 1995 |

|

Sills Burn North

NT8200 |

Marching camp, 2.1 ha. Welfare, H., and Swan, V., Roman Camps in England: the field archaeology, London, 1995 |

|

Sills Burn South

NY8299 |

Marching camp, 1.8 ha. Welfare, H., and Swan, V., Roman Camps in England: the field archaeology, London, 1995 |

|

Sunny Rig

See Haltwhistle |

|

|

Swine Hill

See Four Laws |

|

|

Thorngrafton Common

see Barcombe |

|

|

Throp

NY6365 |

Trajanic fortlet, part of the Stanegate frontier. The site was re-occupied in the 4th century.Frere, S. S., et al Tabula Imperii Romani – Britannia Septentrionalis, London, 1987 |

|

Twice Brewed

See Seatsides |

|

|

Walwick Fell

NY8870 |

Marching camp, 0.5 ha. Welfare, H., and Swan, V., Roman Camps in England: the field archaeology, London, 1995 |

|

West Woodburn

NY8987 |

Marching camp, about 11.0 ha. Welfare, H., and Swan, V., Roman Camps in England: the field archaeology, London, 1995 |

|

Whitley Castle

Epiacum

NY6948 |

1.2 ha fort, occupied from 2nd – 4th century. Garrisoned by Cohors II Nerviorum civium Romanorum (3rd century).Frere, S. S., et al Tabula Imperii Romani – Britannia Septentrionalis, London, 1987 |

|

Written Crag

see Fallowfield Fell |

|

|

Yardhope

NT9000 |

2.0 ha marching camp. Welfare, H., and Swan, V., Roman Camps in England: the field archaeology, London, 1995 |

|

|

|

OLDHAM

|

Castleshaw

Rigodunum

SD9909 |

Late Flavian fort, of 1.3 ha. This was ucceeded by a fortlet (0.3 ha) of Trajanic date. Tiles stamped Cohors IIII Breucorum (see Slack, West Yorkshire) suggest it provided the garrison for the fortlet. Shotter, D. Romans and Britons in North-West England, Lancaster 1993 |

|

|

|

REDCAR AND CLEVELAND

|

Huntcliff NZ6821 |

Late 4th century coastal watch tower. One of a group that includes Filey, Ravenscar Goldsborough, and Scarborough (North Yorkshire). Wilson, P., Aspects of the Yorkshire signal stations in Maxfield and Dobson (eds) Roman Frontier Studies 1989, Exeter, 1991, pp124-147 |

|

|

|

EAST RIDING

|

Brough-on-Humber Petuaria

SE932 |

Marching camp Welfare, H., and Swan, V., Roman Camps in England: the field archaeology, London, 1995

1.8 ha Flavian fort that was maintained as a stores base until the early 2nd century. Garrisoned at some time? by Numerus Supervenientium Petueriensium a unit recorded at Malton in the late 4th century.

Naval base?

Wacher, J. S., Excavations at Brough on Humber 1958-61, London, 1969 |

|

Hayton

SE8145 |

Flavian fort, 1.5 ha Johnson Britannia IX (1978) p57-114 |

|

|

|

ROTHERHAM

|

Templeborough

SK4191 |

A timber fort, 2.6 ha, built circa 55 AD.Succeeded by a Trajanic fort of 2.1 ha that had a stone wall. It was held until circa 180 AD.

A second stone fort, 1.8 ha was possibly held until mid 4th century. Garrisoned by Cohors IIII Gallorum equitata (early 2nd century)

Buckland, P. C., Roman South Yorkshire: a source book, Sheffield, 1986 |

|

|

|

SUNDERLAND

|

Wearmouth

Dictum?

NZ4057 |

4th century fort?Dictum is recorded in the Notitia Dignatatum and should lie close to Wearmouth, although no fort has been found.

Rivet, A. L. F., and Smith, C., The Place names of Roman Britain, Batsford, 1981 |

|

|

|

NORTH TYNE

|

Wallsend

Segedunum

NZ3066 |

Eastern terminal fort, 1.7 ha, of Hadrian’s Wall. Garrisoned by Cohors II Nerviorum civium Romanorum? (2nd century?) and Cohors IIII Lingonum equitata (3rd-4th century).Frere, S. S., et al Tabula Imperii Romani – Britannia Septentrionalis, London, 1987 |

|

|

|

SOUTH TYNE

|

South Shields

Arbeia

NZ3667 |

Two periods of wooden buildings, extending back to the Flavian period? A stone fort was built around 160 AD as a late addition to Hadrian’s Wall. During Severus’s reign it was expanded and changed its role to a stores base (with 22 granaries) to support operations in the northern Britain.

Around 220 AD it was re-organised as a more conventional fort and occupied until the 4th century. Garrisoned by Cohors V Gallorum (3rd century) and Numerus Barcariorum Tigrisensium (4th century).

Frere, S. S., et al Tabula Imperii Romani – Britannia Septentrionalis, London, 1987 |

|

|

|

WAKEFIELD

|

Castleford

Lagentium

SE4225 |

Fort, early Flavian of unknown size, but larger than its successor.Succeeded by a fort, 3.2 ha, in the period 80 – 90 AD. Garrisoned by Cohors IIII Gallorum equitata (early 2nd century).

Frere, S. S., et al Tabula Imperii Romani – Britannia Septentrionalis, London, 1987 |

|

|

|

YORK

|

Bootham Stray

SE5954 |

Two temporary camps now visible (18th Century reports are of eight camps), 0.9 ha and 1.1 ha, training site for the legions based at York?Welfare, H., and Swan, V., Roman Camps in England: the field archaeology, London, 1995 |

|

York

Eburacum

SE6052 |

Legionary fortress, 20.2 ha, built circa 70 AD by Legio VIIII Hispana.Legio VI Victrix replaced them circa 120 AD.

Frere, S. S., et al Tabula Imperii Romani – Britannia Septentrionalis, London, 1987 |

|

|

|

NORTH YORKSHIRE

|

Aldborough

SE4066 |

Fort? Flavian?Frere, S. S., et al Tabula Imperii Romani – Britannia Septentrionalis, London, 1987 |

Bainbridge

Virosidum?

SD9390 |

Flavian fort or fortlet; succeeded by a fort, 1.1 ha built circa 100 AD. The site was unoccupied 140 – 160 AD. The fort was rebuilt circa 200 AD. Garrisoned by Cohors VI Nerviorum (3rd-4th century).Frere, S. S., et al Tabula Imperii Romani – Britannia Septentrionalis, London, 1987

|

Brompton on Swale

SE2299 |

Stores base? on the opposite bank of the Swale from CatterickFrere, S. S., et al Tabula Imperii Romani – Britannia Septentrionalis, London, 1987 |

|

Breckenbrough

SE3783 |

Marching campWelfare, H., and Swan, V., Roman Camps in England: the field archaeology, London, 1995 |

|

Buttercrambe Moor

SE7156 |

Temporary camp Horne, P. and Lawton, I., Britannia XXIX, 1998 pp327-329 |

|

Carkin Moor

NZ1608 |

Fort, 1.0 haWelfare, H., and Swan, V., Roman Camps in England: the field archaeology, London, 1995 |

|

Catterick

Cataractonium

SE2299 |

Flavian? fort. The site was re-occupied from the mid 2nd- 4th century. See also Brompton on Swale.Frere, S. S., et al Tabula Imperii Romani – Britannia Septentrionalis, London, 1987 |

|

SE2399 |

Marching campWelfare, H., and Swan, V., Roman Camps in England: the field archaeology, London, 1995 |

|

Cawthorn

SE7890 |

Two forts one late 1st century? Temporary camp

Frere, S. S., et al Tabula Imperii Romani – Britannia Septentrionalis, London, 1987 |

|

Eggborough

SE5857 |

Fort?Britannia XXX, 1999, pp340-1 |

|

Elslack

Olenacum?

SD9249 |

Flavian fort, 1.3 ha that was occupied until c 120 AD and again around 150 AD. A 2.2 ha fort was built in the 4th century that was garrisoned by Ala Herculea.Frere, S. S., et al Tabula Imperii Romani – Britannia Septentrionalis, London, 1987 |

|

Filey

TA1281 |

Late 4th century coastal watch tower. One of a group that includes Goldsborough, Ravenscar, Scarborough and Huntcliffe. Wilson, P., Aspects of the Yorkshire signal stations in Maxfield and Dobson (eds) Roman Frontier Studies 1989, Exeter, 1991, pp124-147 |

|

Goldsborough

NZ8315 |

Late 4th century coastal watch tower. One of a group that includes Filey, Ravenscar, Scarborough and Huntcliffe. Wilson, P., Aspects of the Yorkshire signal stations in Maxfield and Dobson (eds) Roman Frontier Studies 1989, Exeter, 1991, pp124-147 |

|

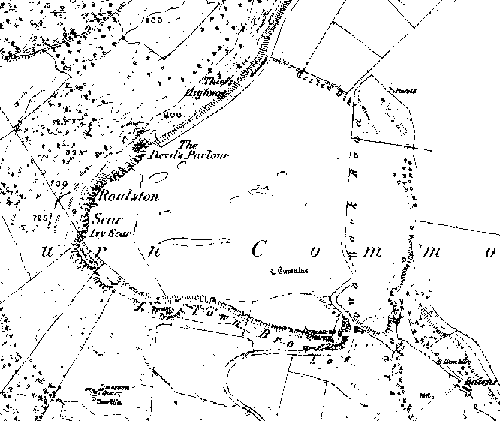

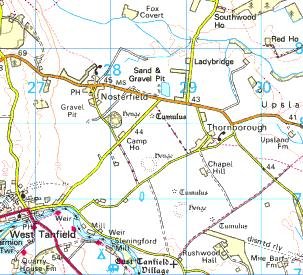

Healam Bridge

SE3283 |

Fort? Flavian?Frere, S. S., et al Tabula Imperii Romani – Britannia Septentrionalis, London, 1987 |

|

Lease Rigg

NZ8104 |

Flavian fort, 1.1 ha. It was abandoned circa 120 AD.Frere, S. S., et al Tabula Imperii Romani – Britannia Septentrionalis, London, 1987 |

|

Long Preston

SD8358 |

Fort?Frere, S. S., et al Tabula Imperii Romani – Britannia Septentrionalis, London, 1987 |

|

Malham

SD9165 |

Flavian marching camp (8.2 ha). Frere, S. S., et al Tabula Imperii Romani – Britannia Septentrionalis, London, 1987 |

|

Malton

Derventio

SE7971 |

Early Flavian small fortress (?) of circa 8.9 ha. A late Flavian fort, 3.4 h succeeded it and was held until circa 120 AD and again from circa 160 AD.

The fort was reconstructed in the 3rd century. Garrisoned by Ala Gallorum Picentiana (late 2nd century) and Numerus Supervenientium Petueriensium (late 4th century).

Frere, S. S., et al Tabula Imperii Romani – Britannia Septentrionalis, London, 1987 |

|

Newton Kyme

Praesidivm?

SE4545 |

Two Flavian forts, of circa 1.3 ha and 4.0 ha Frere, S. S., et al Tabula Imperii Romani – Britannia Septentrionalis, London, 1987 |

|

|

Two possible temporary camps, one overlain by the fort is at least 7.5 ha.Boutwood, Britannia XXVII, pp340-3 (1996) |

|

Ravenscar

NZ9801 |

Late 4th century coastal watch tower. One of a group that includes Filey, Scarborough, Goldsborough and Huntcliffe. Wilson, P., Aspects of the Yorkshire signal stations in Maxfield and Dobson (eds) Roman Frontier Studies 1989, Exeter, 1991, pp124-147 |

|

Roall

SE5625 |

1.3 ha Flavian fortBritannia XXIV (1993) pp243-7 |

|

Roecliffe

SE3866 |

Early? Flavian fort, 2.5 ha Britannia XXV (1994) pp265-6 |

|

Scarborough

TA0589 |

Late 4th century coastal watch tower. One of a group that includes Filey, Ravenscar, Goldsborough and Huntcliffe. Wilson, P., Aspects of the Yorkshire signal stations in Maxfield and Dobson (eds) Roman Frontier Studies 1989, Exeter, 1991, pp124-147 |

|

Wath

SE6774 |

Marching camp, 4.9 haWelfare, H., and Swan, V., Roman Camps in England: the field archaeology, London, 1995 |

|

Wensley

SE0889 |

A Flavian fort, 1.2 haFrere, S. S., et al Tabula Imperii Romani – Britannia Septentrionalis, London, 1987 |

|

|

|