The Ninth Legion

By D. Mark Sansom BSc. (Hons)

The Ninth Legion Hispana: The evidence for its presence and campaigns in Britain

The inspiration for this work came from the author Rosemary Sutcliff and her book ‘The Eagle of the Ninth’ which she wrote in 1954. Although a fictional book it was based on a fact believed in at that time. In the 1990’s many people still refer to the Ninth as the ‘Lost Legion’; this response has caused me to question whether a legion had been lost in Roman Britain. It seemed to be an easy task to prove this theory, or disclaim it as a fantasy. However, it soon became apparent that nobody had ever established once and for all, that the Ninth had ever been based in Britannia. It has always been assumed they were, but I had to search for evidence to satisfy myself that they were based here. Research soon revealed that there were several references, to the Ninth in Britain and a quantity of archaeological artefacts have been recovered bearing the unit’s title; however, in total there are only 3 Literary references, 1 Monumental inscription, 1 Altar, 7 Tombstones and a quantity of Stamped Tile. This is not a lot to base a theory that the whole legion was based in Britain during the Roman Occupation. From the evidence available I have attempted to reconstruct the unit’s movement around the province based on the assumption that it was indeed present at this time.

In 43AD the Ninth Legion is thought to have landed at Richborough with the rest of the Roman invasion force comprising the Second, Twentieth and Fourteenth Legions. The invasion force was under the command of Aulus Plautius who was the governor of Pannonia just prior to the Claudian invasions. The Ninth Legion would have been only a part of this massive invasion force numbering 5500 men, not including the auxiliaries who were attached to the legion; these would number approximately 5000. The Roman historian Dio writes the only known contemporary account of the invasion (DIO LX, 19-22. He does not name the Legions involved in the fight but from evidence of later years we know the numbers and names of these legions. The Ninth Legion commander, therefore, probably had 10.000 men under his command

The Ninth Legion is thought to have advanced north eastwards into Norfolk – Suffolk area.. In doing this it would have had to cross the river Medway. It is possible that at this time, the Ninth Legion was still in company of the Fourteenth and Twentieth Legions. It was during this crossing that the Romans met strong resistance by the native British army under joint command of Caratacus and Togodumnus. The battle was fierce and lasted two days, so the historian Dio tells us. Caratacus escaped the Roman onslaught, and fled to Wales.

The ninth Legion having crossed the Medway, probably advanced up into the friendly territory of the Iceni in Norfolk, a client Kingdom under the rule of King Prasutagus. The arrival of the Emperor Claudius, to take Colchester was probably only a military side show; the area is already likely to have been secured by the Ninth Legion. There is no evidence to support the fact that the Ninth took part in this action, or even if the Ninth was present in Britain during these early actions. It would, however, seem more than likely it was since Aulus Plautius was the Governor of the province they were based in, just prior to the invasion of Britain.

The archaeological evidence for the bases of the Ninth Legion is not present until it moved to a fortress at Lincoln in about 66AD; prior to that there are two strong possibilities for bases of the unit. The first has been located at Longthorpe in Cambridgeshire, near modern-day Peterborough. The second has been located at Newton on Trent in Nottinghamshire. These are vexillation fortresses, and it is possible that the Ninth Legion was, at this time, split into several small units. A third early vexillation fortress has possibly been located at Lincoln; a later fortress is known but this seems to predate it.

It is probable that the tribes of Eastern England had not been totally pacified, and as such needed constant monitoring by the Roman Military, which could explain why the Ninth Legion was split into at least two parts. These vexillation fortresses were occupied until about 66AD when the Ninth legion moved further North. Before this move, the legion and the Roman Province suffered a drastic set back.

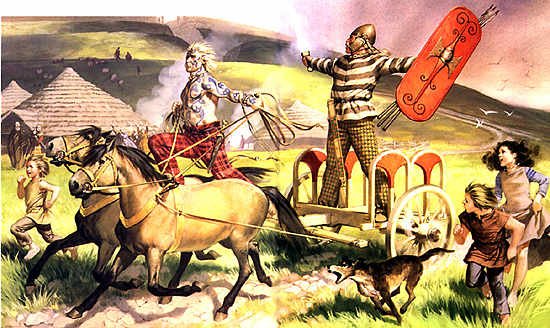

The first positive proof of the Ninth Legion being on campaign in Britain is during the Boudican Revolt of 60-61 AD. The death of King Prasutagus of the Iceni, and the handling of his will by the Romans, caused his wife Boudica to raise an army of natives and go on the rampage in the East of England. Boudica’s first target was the colonia at Colchester, and the Romanized people who lived within the area.

The majority of the Roman army was away on campaign in Wales, under the command of Suctonius Paullinus. It would seem that the only legion available to deal with the revolt was the Ninth under the command of Petilius Cerialis. It is known that the Ninth Legion was sent to deal with the trouble and suffered appalling losses because the historian Tacitus tell us:

The victorious Britons also intercepted Petilius Cerialis, the legate of the Ninth Legion, as he was advancing to the rescue, routed the legion, and slaughtered its infantry contingent. Cerialis escaped with his cavalry to their camp and found shelter behind its defences (ANNALS,XIV, 32)

If this passage is read on its own, it would seem that the Ninth Legion was totally destroyed apart from its 120 cavalry, and Cerialis. The scale of the destruction only becomes apparent when the author Tacitus wrote:

Caesar increased troop numbers with 2000 legionary soldiers sent from Germany together with eight auxiliary cohorts and 1000 cavalry. On arrival the Ninth Legion was brought up to strength in terms of legionary troops (ANNALS XIV, 38)

The worst losses the Ninth Legion could have received was the loss of 2000 infantry, almost half of the legion. If the evidence from one of the fortresses of the Ninth Legion at Longthorpe is correct then only part of the Ninth Legion was involved in this action. The legion would have been sent to try and crush the revolt either after Suetonius Paulinus ordered the legion to crush it, or word of a revolt was received from the inhabitants of Colchester.

It would seem from Cerialis’ career that he was a rash and impetuous soldier. In the case of this revolt he seems to have pushed his men too hard; as he marched he was careless and the legion was ambushed by the Britons. It would seem likely that the Legion was ambushed on the march as if it had time to come to battle drill it could possibly have won the engagement.

The fact is that the Ninth Legion may have suffered a loss of around 2000 men and Cerialis retreated to his base with what was left of his cavalry contingent. The base he came from, and ultimately retreated to, is likely to have been the Vexillation fortress at Longthorpe in Cambridgeshire. The first fortress (Longthorpe 1) on the site is approximately 27 acres in area. It was excavated between 1967 and 1973 and shows that emergency defences cut the camp to under half this size (Longthorpe 11), an area of 1 1 acres. The buildings within Longthorpe 11 show no evidence of being reorganised and it may be possible to say that these defences were a panic measure built by Cerialis in the fear that Boudica would follow and attack what was left of the Ninth Legion.

It would seem that only half of the legion was based at Longthorpe 1 prior to the Boudican revolt; there are two other places in the area that may have housed elements of the Ninth at this time. The first may be at the vexillation fortress of Newton on Trent and the second could be at Lincoln. Wherever they were based it must be assumed that that area was also under threat of revolt since there is no evidence that they went to the assistance of Cerialis.

It is likely that after the revolt the Ninth legion, once it had been brought back up to strength, moved from Longthorpe and Newton on Trent to two new bases, the first a new fortress at Lincoln and the second at Rossington or Osmanthorpe. These have all been identified as pre-Flavian vexillation fortresses. The new fortress at Lincoln is presumed to have been built by the Ninth Legion due to the amount of burials of soldiers of the Ninth found below the fortress. There are unfortunately no monumental inscriptions to say that the Ninth built the new fortress, but it may be inferred by the presence of these burials.

It would seem that the Ninth Legion was again split into at least two, if not three parts. The next problem the Ninth Legion probably had to deal with was the feud in Brigantia between Cartimandua and her ex-husband Venutius. Trouble in Brigantia had been brewing since 52AD when the Queen, Cartimandua handed over the fugitive Leader Caratacus who had fled to Brigantia in the hope of evading the Romans. It seems that the Queen had been pro – Roman since they had invaded, although her husband Venutius seemed more cautious about the Romans. It would also seem from the evidence that she had taken on the luxuries of Rome such as fine glass wares and wines. Cartimandua must have been loyal to the Romans because in 60AD when Boudica revolted the tribe of the Brigantes did not rise in support of her.

This fragile peace to be found in Brigantia may have been the reason that over half of the Ninth Legion did not come to the aid of Cerialis. Since it was based around the edge of Brigantia it was probably expecting trouble. The peace only lasted until 69AD when the Queen divorced her husband, Venutius, and took her armour-bearer, Vellocatus, as a lover.

The Roman army at this time was in discord as each British legion supported a different candidate to become the new emperor of Rome. It is possible that elements of the Ninth Legion were removed from Britain at this time to support one of the candidates for emperor. Cartimandua was no longer supported by the Roman army and her ex-husband took the chance to take over Brigantia, Tacitus tells us that Cartimandua, was only just rescued, by a force of auxiliaries. (HIST 111,45)

When Petilius Cerialis returned to, Britain in 71 AD as the governor his first role was to invade Brigantia. The Ninth Legion at this time moved to York which was on the edge of Brigantian territory and some of the legion are likely to have been based at Malton. Brigantia was now feeling the power of the Roman force and the historical record does not tell us what happened to Venutius but it is likely that he met the might of the Ninth legion at Stanwick, the supposed centre of Brigantia, in 72AD.

After the defeat of Venutius it is likely that the Ninth legion tried to pacify the Brigantes, and under the new governor Julius Frontinus 73-77AD embarked on the consolidation of the newly conquered territory. It was during this time that the legion would have started building a new permanent base at York which could house the whole legion in comfort. It was not until the governorship of Agricola that the rest of Brigantia was subjugated, possibly agency of the Ninth Legion.

In 78AD Agricola was made governor of Britain and his first task as governor was to sort out the remnants of trouble in Brigantia. The natural choice in making this advance northwards would have been the Ninth Legion as it was based at York and must have been familiar with the surrounding area. The historian Tacitus tells us a great deal about the campaigns of Agricola in Britain, but he omits to say which legions were involved and where they were used The dates of all of Agricola’s campaigns are questioned , fiercely by historians and for the purposes of this text two years will be given in each case. Agricola started his first campaign in. 78/79AD and he is thought to have reached as far north as the Bowes-Tyne line, later to become Hadrian’s wall, by the end of the first season. Tacitus tells us that it was a two pronged attack moving up either side of the Pennines and it would seem probable that the Ninth Legion advanced up the eastern side of the Pennines, possibly as far as Corbridge where Agricola established a supply area.

In 79/80AD Agricola again advanced and it would seem likely that the Ninth went with him. It is possible at this stage that the Ninth was combined with another legion for this advance, which other legion is not known. By the end of the 79/80AD campaign it could be possible that the Ninth Legion was returned to York. No mention of it occurs until the campaigns of 82/83AD, however, it may be possible that it was responsible for the building of the new legionary fortress at Inchtuthil, and may have been stationed there.

In 82/83AD the Forth-Clyde line was crossed by Agricola and the Ninth Legion were involved; Tacitus tells us that they were attacked at night in their camp:

‘As soon as the enemy got to know of this they suddenly changed their plans and massed for a night attack on the Ninth Legion.’ (AGRICOLA,26)

Tacitus also describes the Ninth legion Maxime invalida, weakest of all. A possible reason for this is because detachments from the Ninth had been sent from Britain to Germany to fight the Chatti in Chatten wars. an inscription records the fact that a senior Tribune of the Ninth won decorations during the war (ILS 1025).

It would seem that detachments were taken from all the British legions, leaving Agricola with a smaller force than was desirable. The defeat of the Ninth would have been on a large scale for it to be worthy of a note by Tacitus. It could, however, just be another ploy to make Agricola look good when he won the day and the Ninth. It is not known where this attack on the Ninth took place but it has been suggested that a marching camp sited near Dornock (NN 890180) may fit Tacitus’s story; being 33 acres it could have easily accommodated a legion under canvas.

It is not known what happened to the Ninth after it was attacked. Depending on its condition it would either have continued to campaign with Agricola or withdrawn either to Inchtuthil or back to York. It would seem likely that, because short of troops. Agricola retained the Ninth legion in the field until the end of the campaign. After Agricola was recalled from Britain his conquests in Scotland were let go, and the army retreated back to the Bowes-Tyne line; the Ninth Legion may have moved back to York. Agricola was a prolific fort builder and it may be possible that many of the forts built in his name were constructed by the Ninth legion. From the evidence of these forts it is almost possible to plot Agricola’s campaigns.

The Ninth after its move back to York probably settled into a more mundane state of existence, patrolling the local area and bringing the unit back up to strength, after the mauling it received in Scotland. Between December 107AD and December 108AD the legion erected a monumental inscription dedicated to the Emperor Trajan (RIB665) over the south-eastern Gate of a rebuilt stone fortress. The Ninth may have used this period to redevelop the fortress at York and many of the buildings may have been replaced.

This inscription is only one of the ways that the Ninth is known to have built York, there have been three other inscriptions set up to men of the Ninth Legion, including a particularly fine one commemorating the standard-bearer Lucius Duccius Rufinius (RIB 673).

The evidence for the Ninth legion rebuilding in stone also comes from the stamped tiles that they used, these were embossed with the title LEG IX HISP. The inscription dedicated to Trajan is the last dated reference to the Ninth Legion being present in Britain, but it might not mean that the legion was absent from the province after that date. It would seem more than likely that the Ninth moved from York in about 120AD when the Sixth Legion appears to have moved into the fortress at York.

It is highly likely that the Ninth legion moved to Carlisle, which was probably established by Petilius Cerialis in 71 AD. After it vacated the fortress at York, there is evidence of the legion’s presence at Carlisle in the form of stamped tile embossed with the stamp LEG VIIII HISP. These tiles were being produced five miles south east of Carlisle at the recently identified legionary tile depot at Scalesceugh. A magnetometer survey of the site has identified 24 kilns which were probably used to produce enough tile to build the Ninth Legion’s new fortress at Carlisle.

It can be seen the Ninth started stamping the tiles from the kilns at Scalesceugh with the title LEG VIIII HISP. No tiles bearing this stamp have yet been found in the Vale of York, therefore, it can be assumed that the legion had several centres of tile production.

It should also be noted that stamped tiles bearing the title LEG VIIII HISP have also been found at Stanwix; so the legion may have again been deployed in two places in the north. Until further work is done on these two sites it will be difficult to prove that the Ninth was based at these sites. Inscriptions from the fort at Stanwix suggest that it was the home of the Ala Petriana; if this is correct then the Ninth may have built this fort. If the whole legion did move to Carlisle, there must have been a reason for the move, and one may assume that the reason was that it was used to help build the western end of Hadrian’s wall. As this half of the wall was built in turf the inscriptions would have been made of wood and that is probably why they do not survive. There must have been as many inscriptions on the turf wall as there were on the stone parts of Hadrian’s wall, but, it is a question of archaeological survival that means no inscriptions survive in wood to prove or disprove their presence.

It is unlikely that the Ninth stayed very long in Carlisle or Stanwix. The archaeological record shows that they then moved from Britain to Nijmegan in Holland to replace the Tenth Legion Gemina, where tiles and mortaria have been found bearing the Ninth legion’s stamp.

The history of the Ninth Legion in Britain and the campaigns it took part in are by no means certain. Due to so little archaeological and written evidence this task is almost impossible, but fortunately there is enough evidence to be certain of several things. Several members of the Ninth Legion are known to have been buried in this country, at both Lincoln and York. The legion built a gate in York, and dedicated it to emperor Trajan.

The Ninth Legion also stamped its tiles with the title LEG IX HISP or LEG VIIII HISP, at several locations around the north of Britain. There are only two campaigns that the Ninth are known to have taken part in during the Roman occupation, the first was the Boudican revolt and the second was with Agricola during his campaigns in Scotland.

As more archaeological discoveries are made the evidence for the Ninth legion being present in Britain may increase, and it could eventually be possible to chart their campaigns with a greater deal of accuracy.

It must, however, be remembered that the picture of Roman military occupation in Britain may be far more complicated than has been assumed by historians. This paper has used the evidence available for the Ninth legion to try and fit it into the historically known facts about the Roman campaigns in Britain. It must be noted that this article should be regarded as an individual’s interpretation and as such should be treated in this light. Due to the scope of this subject there may be many alternative suggestions to when and where the Ninth Legion campaigned in Britain.

A Brief History Of The Ninth Legion Hispana

The Ninth Legion has its origins in the pre-Augustan period and probably goes back to Julius Caesar’s Ninth legion based in Gaul during 58BC and may have come from Dubrovnic in the former Yugoslavia. Evidence suggests that at the beginning of the first century AD it may have been based at Sisca, in. Pannonia. It is known to have won battle honours in both Spain and the Balkans and in light of this carries the titles HISPANA and MACEDONICA (ILS 928). It seems, for reasons unknown that it only used the title Hispana as common practice and for official stamps.

During the units stay at Sisca it was called for service in Africa to control a riot that took place in 17-24 AD, but it returned before the end of the revolt. The legion under its commander Aulus Plautius, commander of the Roman invasion of Britain, is thought to have moved from Pannonia to Britain in 43AD as part of the invasion force.

The legion is known to have played a key role in the Boudican revolt of 60AD (ANNALS XIV,32) and after this action needed 2000 replacements (ANNALS XIV, 3 8).

In the year 69AD troops were taken from Britain to support Vitelius in his bid to become emperor, it is possible that elements of the Ninth were involved at this time (HIST.2,57).

In 79AD Agricola advanced northwards towards Scotland by an eastern route and it is likely that the Ninth Legion played a key part in this advance as at the time it was based at York (RIB 665).

During another campaign of Agricola in 83AD the Ninth Legion is known to have been attacked in camp at night by the Scots, north of the river Tay (AGRICOLA, 26).

A vexillation of the Ninth Legion was taken from Britain late in 83AD to help in the Chatten wars near the Rhine, in Germany and during that action a senior Tribune of the Ninth won decorations (ILS 1025).

The legion may have been moved up to a new legionary Fortress at Carlisle to assist in the building of Hadrian’s wall in about 122AD.

The legion was removed from Britain sometime between 120-130AD and was relocated to a base at Nijmegan in Holland (BRIT. 1978,381 fn 9).

By 180AD all trace of the lecion had disappeared and it is thought to have been lost in action whilst dealing with the Judean Revolt (DIO LXIX, 13) in 132AD. A list of all the legions found in Rome dating to around 161-180AD (ILS 2288), makes no mention of the Ninth Legion.

Evidence for the Ninth being present in Britain

LOCATION EVIDENCE

YORK INSCRIPTIONS (RIB 659/665/673/680)

TILE STAMPS (BRIT. 1978. 379-382)

LINCOLN INSCRIPTIONS (RIB 2541255/256/2571260)

TILE STAMP (BRIT. 1978,379-382)

CARLISLE TILE STAMPS (BRIT. 1978,379-382)

HILLYWOOD TILE STAMPS (BRIT. 1978, 379-282)

SCALESCEUGH TILE STAMPS (BRIT. 1978,379-382)

OLD WINTERINGHAM TILE STAMPS (BRIT. 1978, 379-382)

ALDBOROUGH TILE STAMPS (BRIT> 1978.379-382)

TEMPLEBOROUGH TILE STAMPS (BRIT. 1978, 379-382)

MALTON TILE STAMPS (BRIT..! 978, 379-382)

SLACK TILE STAMPS (BRIT. 1978, 379-382)

CASTLEF0Ki) I’ILE STAMPS (BRIT> 1979,288)

STANWIX TILE STAMPS (BRIT> 1986,,441)

B) LITERARY:

AUTHOR BOOK PASSAGE

TACITUS ANNALS XIV,32

TACITUS ANNALS XIV,38

TACITUS AGRICOLA 26

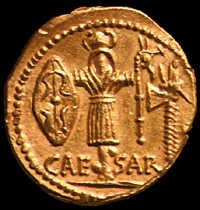

L. Hostilius Saserna, silver denarius, Rome 48 BCE (HCRI 18)

L. Hostilius Saserna, silver denarius, Rome 48 BCE (HCRI 18) The sister coin to the above shows a female Gaul with a typical Celtic carynx behind. She has often been called Gallia, a concept that would be absolutely foreign to the tribal Celts. More likely she represents a captive. Hear hair is long in a non-Roman fashion and almost modern in appearance, perhaps limed and forming dreadlocks. Her face is pretty in contrast to most Roman females depicted on coins.

The sister coin to the above shows a female Gaul with a typical Celtic carynx behind. She has often been called Gallia, a concept that would be absolutely foreign to the tribal Celts. More likely she represents a captive. Hear hair is long in a non-Roman fashion and almost modern in appearance, perhaps limed and forming dreadlocks. Her face is pretty in contrast to most Roman females depicted on coins.