Timeline 60BC – 138AD

This timeline is focussed on the British Celtic culture and those cultures which had influence on the British Celts. It Read more

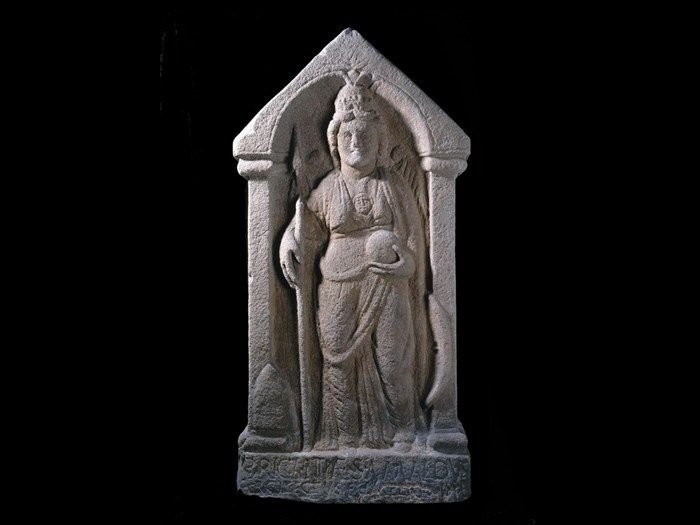

Cartimandua

Yorkshire, and much of northern Britain was also ruled by a queen, the most powerful ruler in Britain in fact. Read more

Caratacus

Caratacus was highly influenced by the Druids, and both he and his brother Togodumnus were among the leading lights of Read more

Cerialis Petillius

Quintus Petillius Cerialis Caesius Rufus was the son-in-law of Vespasian Cerialis and became Governor of Britain in AD.71; his instructions Read more

Julius Caesar

Ask anyone to name a famous Roman character, and the name of Julius Caesar is sure to be the most Read more

Vespasian

Born in the year 9 at Reate, north of Rome, Vespasian was the son of a tax collector, Flavius Sabinus Read more

Augustus

Suetonius wrote of him: He was very handsome and most graceful at all stages of his life, although he cared Read more

Claudius

Tiberius Claudius Nero Germanicus was born Lugunum in 10 BC, the youngest son of Nero Drusus, brother of Tiberius. He Read more

Celtic Gods

Many Celtic deities seem to have been associated with aspects of nature and worshipped in sacred groves. Some appear in Read more

Stanwick Iron Age Hill Fort

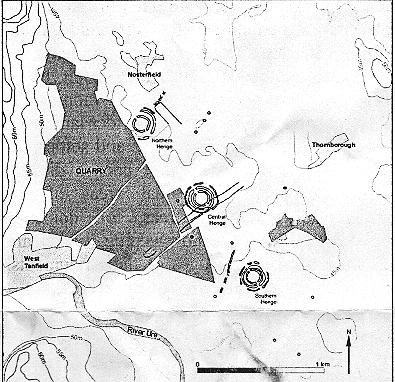

This note describes a partial perimeter walk of the largest hill fort in England. This walk covers some six miles and takes in the major extend of the fort and covers the two stages in it’s development.

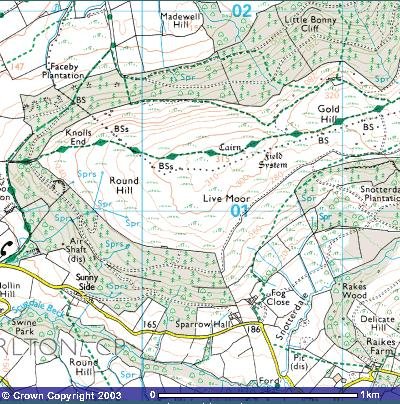

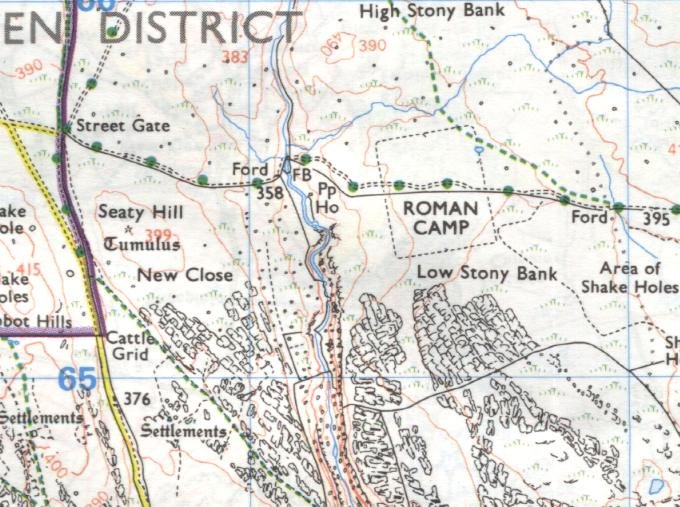

Location:: O/S 1:50,000 map 92 ref, 178123

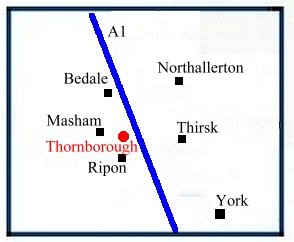

Stanwick is very close to the Scotch Corner junction of the A1, close to Darlington. From Scotch Corner, take the A66 towards Barnard Castle for a couple of miles then take the right turn towards Forcett. The road will take you past part of the defenses, at which point a left turn will take you to Stanwick St John Church, which is a suitable starting point for any visit.

The original Enclosure dates from around 400 BC, so far this has not been mapped but it appears to have been a small settlement.

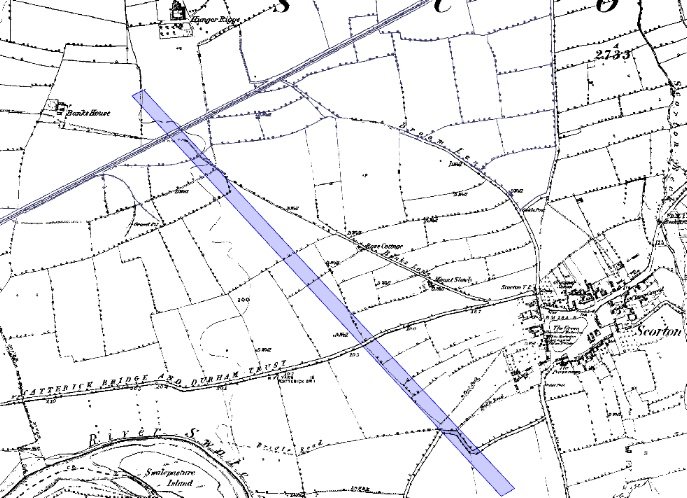

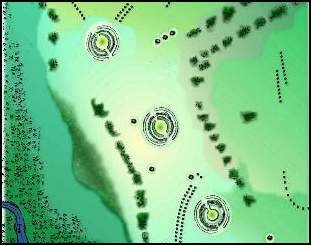

Around 50AD this original enclosure was then replaced with a 650 acre “super fort”. The building of this stage has been widely attributed to Venutius, given the period in history and was abandoned before the end of the 1st century AD. Much later in medieval times a further fortification was “butted up” to its southern outer wall.. The history of this remarkable place is still being pieced together but all indications are that this fort was the most important site for the Brigantes in the immediate run up to the Roman conquest of Brigantia in AD. 69-70. Recent excavations by Colin Haselgrove have to a certain extent conflicted with Sir Mortimer Wheeler’s original evaluation and also in part with the authors. Haselgrove extends the chronology to the middle Iron age and claims that the largest outer wall (Wheeler Phase III) was built first in a growth stage in the mid 1st century AD. This was then subdivided with a smaller better fortified area within. Evidence of high status has been found in the form of a building of a significant and unusual size, accompanied with high status Roman artifacts. Our own site visits indicate that there are significant areas of interest yet to be excavated and it is certain that Stanwick has more secrets to tell. Also certain is that the history of Stanwick holds the key to the story of the Roman conquest of Brigantia in 69-70AD.

In his evaluation Haslegrove seems to conclude that an Earthwork so large was not defensible and it was therefore built as an impressive trading post by Cartimandua just prior to the Romanisation of Brigantia, and fell out of use shortly afterwards.

Recent early days investigations linked with Carl Wark indicate that Venutius may have been responsible for a dike running from Sheffield to Rotherham, possibly on to Doncaster and following the Don up to the Humber. Alongside this at regular intervals are a series of fortified Iron Age camps, of which Carl Wark may be a member. If proven this would indicate that long fortifications were considered defensible, and if this line did show Venutius’ south eastern border, it is unlikely that Cartimandua will have been establishing a trading post at Scotch Corner at the same time.

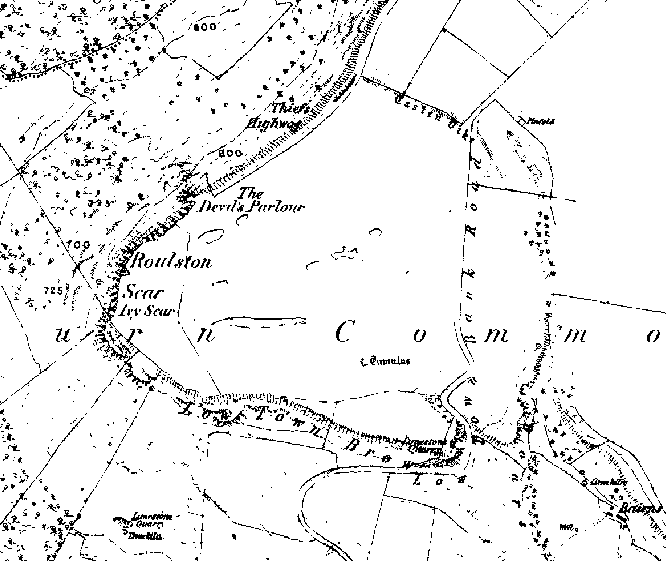

Map of Stanwick, Haslegrove’s outline of the fort in blue.

General description of walk

Approx. Length: 6Miles.

Difficulty: Moderate. Liable to Mud.

Time taken: 5 hours

The Walk

The Walk starts at the Church of Stanwick St John which can be traced back to 850AD, the church and churchyard itself are well worth a second look, the church has in many places reused older carved stone showing weapons, shears and other items. In the oval churchyard there is a Celtic Cross which dates to 850 AD.

Church of Stanwick St John, together with part of the reused carved stone in its interior.

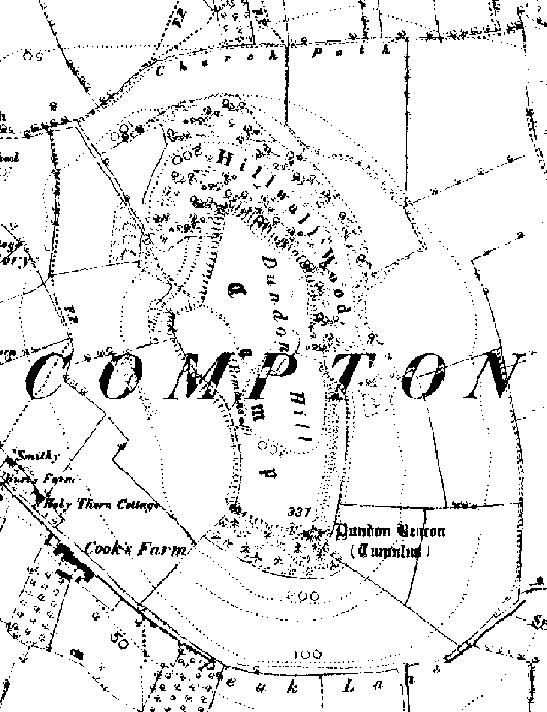

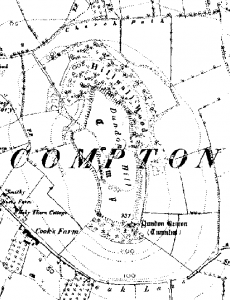

From the Church of Stanwick St John walk along the road down towards Tofts Hill across the Mary Wild Beck and to a footpath into the hill on the right hand side of the road. Take the footpath up through the center of ‘The Tofts’ hill area, this allows a view of what Wheeler regarded as the first phase of the building of Stanwick however Haslegrove with a much more recent excavation has proposed a different chronology and thinks that this was the final phase of building at Stanwick, adding the high status area.

Haslegoves interpretation of his findings at Stanwick indicate that this point is were a small defended settlement was built around 400 AD. The fort occupied broadly the same proportions as can be seen by the current visible enclosure, but had its northern defense closer to the Mary Wild Beck, this is now a 1-2 ft dip around the northern perimeter of the hill fort. Our primary interest is the use of the fort during the middle of the 1st Century AD, at the time when Venutius and Cartimandua ruled a Brigantes split by civil war and ultimately subdued by the advancing Roman army.

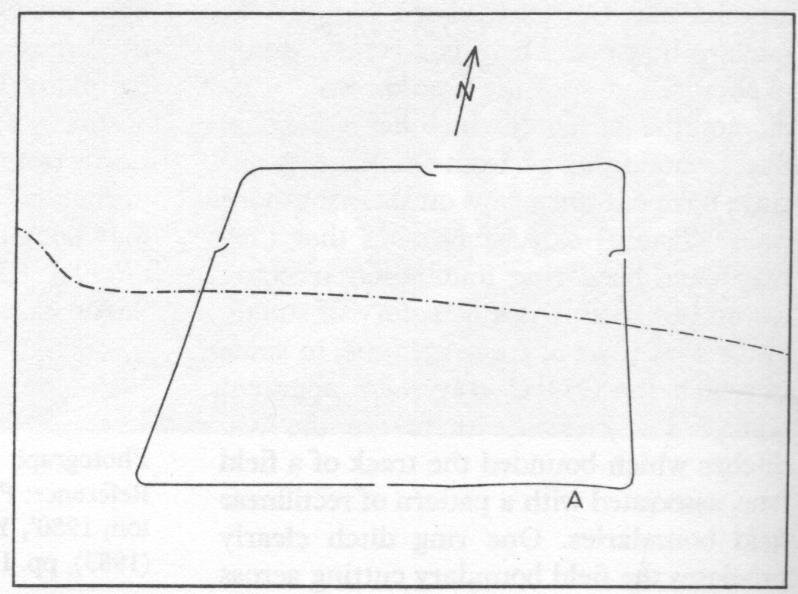

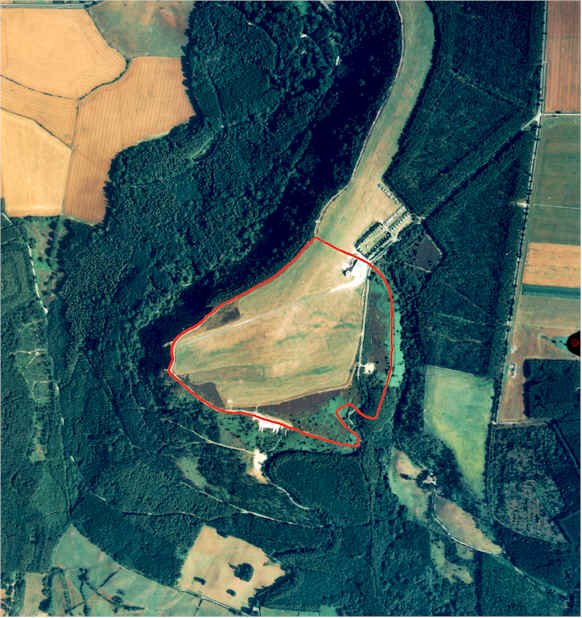

The high status enclosure on Tofts Hill.

The Inner Fort

The earlier fort was completely swallowed by a much larger fortification (original fort 27 Acres, new fort 850 acres) in the middle of the first century AD. The inner sanctum for this new fort was placed directly on top of the original fort, the sight being flattened before hand. Running down the inside of Tofts Hill The Northern the southern defensive wall can be seen, Haslegrove has confirmed the authors earlier opinion that the wall originally continued down the hill to join the Mary Wild Beck, evidence of this can be seen towards the end of the visit. At the top of The Tofts the Southern rampart of the enclosure are very well preserved, but shrouded by undergrowth and trees.

The Southern outer defenses

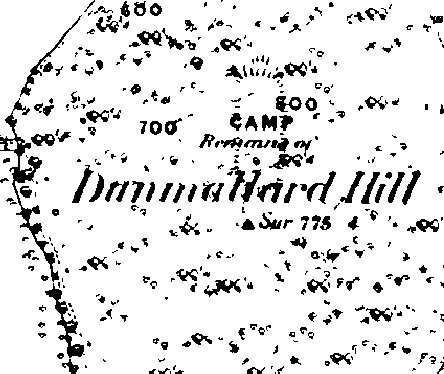

The footpath continues down into the southern heart of the massive main enclosure and eventually turns a sharp right up a prominent hill towards Hill House Plantation. This hill is the obvious focus for a command and control point as it has clear view of the entire southern perimeter.

At the end of the track a road junction appears, continue straight-ahead to meet up with the western defense earthwork at Forcett Park. Although the perimeter has a modern wall, the outer rampart of the fort is still quite tall and can be seen, with what looks like a two meter mound and a four meter ditch.

A point to note about Iron Age walls of this manufacture, typically a third of the mound height will have eroded away and two thirds of the ditches depth would be lost to in-fill, thus a defense which is 9m high in modern times could have easily reached 18m in height when originally built, furthermore it is highly likely that the Brigantian builders would have built a six foot dry stone wall on top of the mound as is evidenced later in the visit.

At the end of the road a further road junction appears, here turn left to walk parallel with Forcett Quarry. It is possible that Forcett Quarry was originally built by the Brigantes as both a defensive measure and as a source for Stone, evidence of an entrance exists at this southwestern corner of the fort. About two hundred metres from the road junction the clear line of the Southern Defense can be seen coming from the direction of Park House. Follow the road past the defenses then turn right, just past the farm building then head Eastwards across Carkin Fields to walk in parallel with the Southern rampart and to approach the medieval intrusion.

Prior to turning it should be noted that one kilometer up this road on the right can be seen what is marked as a moat. Often moats were build over existing earlier fortifications and further investigation may prove worthwhile.

Following the Southern Defensive line, the impressive extent of the defenses becomes apparent, the huge mound that remains of the rampart clearly gives this site its importance. Wheeler estimated that this entire 4.5 mile stretch of was erected within a year or thereabouts, giving credit to the degree of organisation the Brigantes were able to exert.

Whilst crossing Carkin Fields the path crosses from the end of the original field over to the field closer to the ramparts and continues, skirting the right hand side of the field an on to the road junction at the end.

At the B6274 turn left to meet up with the rampart and then turn right to carry on just inside the defenses, heading towards a plantation North West of Park House.

From the road turn right to the interior of the defensive wall. The massive size of the remaining Rampart and Ditch are awe inspiring. Still more impressive is the thought that the rampart, currently about 4m high in places was originally over 30% higher, probably with a 2m dry stone wall on top. The ditch, now some 2m deep, was originally up to 6m deep.

How many occupied Stanwick?

As part of his Maiden Castle excavations Wheeler calculated that a typical occupied hill fort (one which people actually had homes in) could hold up to 100 people per acre, this indicates that Stanwick could have held 85,000 inhabitants. However it has been suggested that Stanwick may have had a significant amount of space for animal enclosures, this has not been proven.

About half way along this stretch of the wall, (OS 182107) there is a circular tower, which was obviously a much later folly. Also at this point and more prominent, is a half-sunken water tank, which looks very interesting, but isn’t.

An interesting point to note is that much of the stone face of the wall has been recently (last 150yrs) used to create much of the deer (HaHa) wall that follows the rampart line. Apart from the obvious destruction of a major piece of archaeology, the fact that the original dry stone topping was close enough to the surface to allow its re-utilisation in the 19th century indicates that it was left intact across this entire stretch and was not therefore a point of incursion by enemy forces (Haslegrove has also made the point that Stanwick does not seem to have been defeated, although Wheeler felt that there were signs of deliberate collapse at the northern rampart, discussed later). This was one factor which led Haselgrove to conclude that it must have been a Roman friendly fort (Cartimanduan) which simply fell out of use rather than being slighted. Given that less than 1% of the rampart area has been excavated this conclusion should not be given a significant amount of weight at this time. Certainly there are large areas of the fort which do not seem to have been slighted.

The Later – medieval? extension

After following the track for about a mile and a half the defenses travel through a plantation, and the track follows the rampart through the wood along a clear track in an easterly direction. Further along this stretch the rampart diminishes to a slight mound and ditch – no more than a 1.2m total drop. Clear evidence that the ramparts at this stage have been collapsed for some time. This however does not look to be due to activity in the Iron or Roman ages. More likely is that this is due to the medieval ‘extension’ which, if Sir Mortimer Wheeler was right, is due to a much later Saxon work, linked to the nearby Scots Dyke.

At the southeastern corner of the fort, the path crosses the defenses and continues in a northern direction immediately outside the eastern perimeter. The entire length of the eastern defense seems to be intact and in much the same condition as the majority of the southern defenses

Stanwick eastern rampart

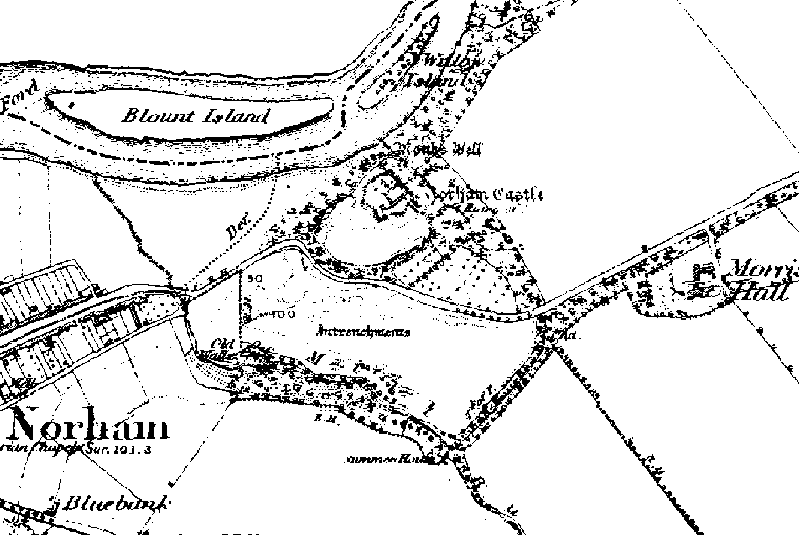

Note. About a mile east of this point is the closest point of Scots Dyke.

Half a mile up the eastern defense the footpath swings northeasterly to join with a nearby road, here turn left and head towards the bridge over Mary Wild Beck, at this point the eastern defense that is being followed disappears into the Beck.

The undefended western defenses?

Both Haslegrove and Wheeler has conjectured that the Mark Wild Beck was used as part of the outer defenses, although Haselgrove has also conjectured that the eastern defense originally continued northwards to encompass Henna hill but there is virtually no evidence of this and given the obvious size and extend of the defenses seen so far this particular stretch is a real conundrum and could be said to add weight to the notion that the fort was not built for defensive purposes, just to impress.

The Mary Wild Beck itself is a couple of foot wide and is very shallow, it is unlikely to have presented a formidable obstacle.

A little way up the road, just over the bridge is a stile on the left which should be taken to follow the Mary Wild Beck towards the start of the southern sweep of the defensive works. Note that OS Pathfinder Series NZ 01/11 goes horribly wrong at this point, stick with Landranger map 92.

The Walk along the Beck is delightful, in the distance the start of the southern rampart can be seen. It has been suggested that dam across the Mary wild beck, would have created a large lake in this whole area, possibly creating a defensive moat around Henah Hill. This lake could have also extended within enclosure, possibly as far as the church but these suggestions are untested.

The ‘Inner Sanctum’ taken from the south, close to the Mary Wild Beck. In the foreground the ditch left by a possible extension to the beck can be seen.

The interior of the fort

The first point of the this part of the defense looks to be a small entrance of some sort. This is the best site on the walk for the partaking of ones packed lunch. To the north is the great furrow that remains of the eastern stretch of the southern sweep of the rampart, curving up the incline at the back of Henah Hill, in its far corner the North Eastern entrance excavated by Wheeler (not visited this trip) can be seen.

Towards the south and south west the northern defenses can be seen curving round to the Beck in all their glory. To the East The Tofts Hill ‘Inner Sanctum’ can be seen. Note that wide furrows in the field to the west of the beck show that the enclosing rampart for the ‘Inner Sanctum’ may have originally extended down to the beck.

Part of the South eastern, from the interior.

The footpath continues along the Beck, through the eastern side of the outer defenses and passes through a very interesting area of ridges, furrows and mounds which so far do not seem to have been excavated. It should be noted that the modern footpath has deviated from that referenced on the OS maps and crosses the beck at a point some 200m before the beck meets the main road.

This is a good point to see the furrows left by the two sets of parallel Earthworks which extend the ‘Inner Sanctum’ to meet the Beck. The first travels from the point of the small bridge up to the nearest house in a northwesterly direction, here it seems to meet the interior forts south eastern defensive wall. The second starts much closer to the church, and is an obvious extension to the line made by the northern rampart.

View from The Mary Wild Beck to The Vicarage

In line with the footpath, the walk continues down the road past the church, and on towards The Vicarage to the north east to turn left onto the main road to Forcett through the center of the southern enclosure and on to the area of the wall that was re-erected by the late Sir Mortimer Wheeler, more than 50 years ago.

Command and Control

At this point it is worth discussing the areas of command and control within the fort. Being so large no single line of sight position exists and therefore it is possible that there would have been a number of command points from which to view and direct activities. The inner fort of Tofts Hill has its most obvious command and control point at the top of the hill close to where the footpath crosses the field. For the Northern defenses a zone of command seems to establish itself at some point central to that part of the enclosure, probably close the middle of this stretch of road.

The southern defenses could not have had a single point of command, and possibly having two. The main control point could have been on the hill heading to Hillhouse Plantation, and a further command post to the south between Hergill Quarry and the unfinished southern entrance would have been required. Obviously a high level of communication will have been required to correctly command a possible defense of the fort.

During his excavation in 1988 Haslegrove came across a high status building with several very deep post holes to one side, suggesting a very tall structure. A further possibility is that this was the central command point, deliberately elevated so as to provide better line of sight communications.

The reconstructed Wall

After about a mile along the road a signpost indicates “Stanwick Fort” and points to a short path to the right of the road, at the end of which is one of the most impressive sights of the visit – Wheelers reconstructed wall.

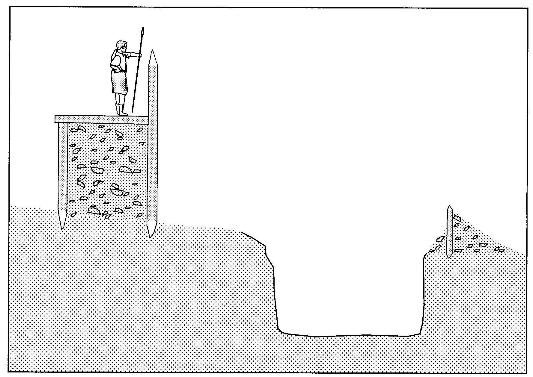

It was here that Sir Mortimer Wheeler excavated and rebuilt a section of the north western defensive wall, and even though he did not rebuild the mound to its original height the structure is certainly impressive.

An interesting aspect of this area of rampart is the hidden nature of much of the northern rampart. Since it is built on flat ground, from even a short distance away the defenses look like a normal dry stone wall, a couple of meters above the ground. A would be invader would not see the true size of the defenses until they were within 100 yards or so. At that point the huge 20-30 foot deep trench would open up before them, with a sheer wall some 4m higher at the other side.

However, it also raises a small problem. Historical evidence of Roman siege tactics show that commonly they would surround the Fort, sometimes building and outer rampart around the besieged fortress (fifteen mile circumference outer valets were known in France). They would then use projectiles to remove the defending soldiers from the ramparts and would fill the ditch and use siege towers in order to gain entry to the fort interior.

Stanwick was built some years after the Roman invasion commenced; Venutius had witnessed many sieges as part of his earlier southern campaigns and had a fair degree of success with his Roman engagements prior to the main advance north. Yet Stanwick seems to do half of the Romans job for them, impressive though they are, surely it would not take the Romans long to throw a few ladders across this section, thus gaining entry. Indeed Wheeler comments that this section of wall had obviously been deliberately collapsed very soon after the unfinished southern entrance had been abandoned. It is therefore likely that this was one of the Roman attack points.

This same point is could be used to strengthen the argument that Stanwick was simply a large trading town, which fell out of use and had no specific anti Roman defensive purpose.

“Wheelers Wall” with a colleague standing at the foot of the ditch.

On departing the Wheeler Wall you will have to retrace the path back to the start of the visit to end the tour.

Conclusions

Given the variance between Wheeler’s notes and those of Haselgrove it is difficult to provide a firm conclusion without running into serious argument However our initial best guess is:

1. The main Stanwick fort was built by Venutius and had a very short life, perhaps no more than ten years, or much less. By AD 75 Stanwick was deserted.

2. It is not clear as to whether Stanwick was defeated by the Roman’s or abandoned, however most of the excavation work has centered within the Tofts Hill area and this is not likely to show signs of siege activity or weaponry used. Stanwick does not appear to have had a large scale incursion, unless the ‘undefended’ south eastern section hides an outer rampart which was completely slighted. There is partial evidence of attack on the South western side.

3. The high status Roman artifacts represent Venutius’ ‘spoils of war’ after his defeat of Cartimandua and may have been captured from her ‘palace’. Another, wilder explanation is that Roman goods found their way to Venutius as payment for his help and support of a losing faction during the civil war of 69AD.