Cana Barn Henge - 1805 OS map

Cana Barn Henge, Copt Hewick, North Yorkshire

Location

Cana Barn Henge (grid reference SE 3608 7185) lies c. 3 km north‑east of Ripon and 800 m south‑east of the River Ure on gently undulating farmland between the villages of Copt Hewick and Marton‑le‑Moor. The monument sits at ≈ 38 m OD on the fertile Vale of Mowbray, midway along the celebrated alignment of great henges that runs from the Devils’ Arrows at Boroughbridge north‑west to the Thornborough complex.

Cana barn henge - OS Series 1 - National Museum of Scotland

Geological & Topographic Setting

The henge occupies a low gravel terrace formed by Devensian outwash over Permian Magnesian Limestone. Local soils are free‑draining brown earths that favour arable cultivation and would have provided a well‑drained platform overlooking the wide alluvial meadows of the Ure. The river’s palaeochannels, visible on LiDAR, emphasise that Cana Barn commanded a liminal zone between dry ground and wet valley floor—an echo of the water‑edge settings favoured by several other North Yorkshire henges.

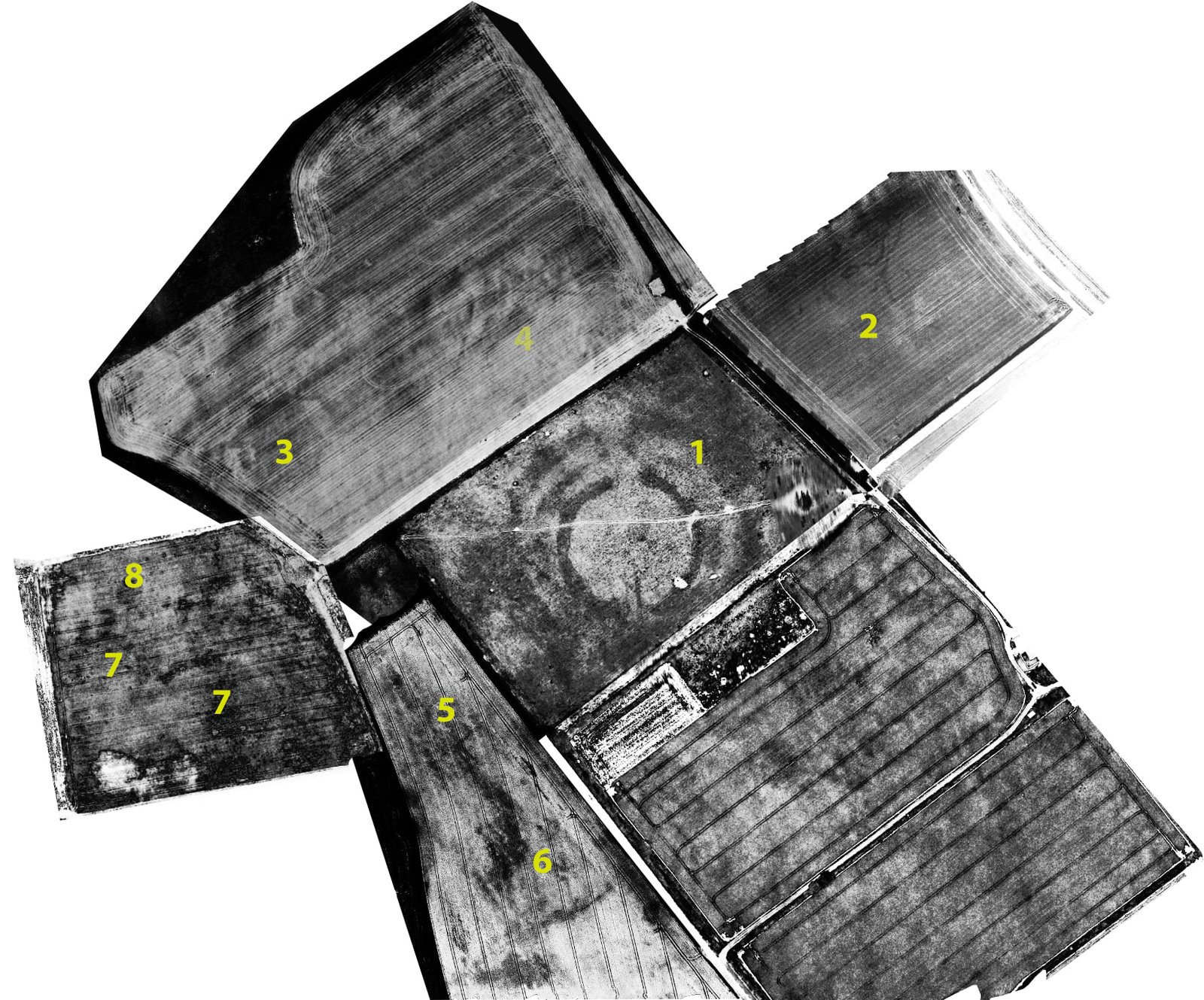

Cana Barn Henge - LiDAR - LiDAR Finder

Form & Dimensions

Aerial photography and LiDAR show Cana Barn as a near‑circular enclosure defined by a broad inner ditch (4–10 m wide) and a slight external bank. The outer diameter is c. 174 m, making it one of the larger henges in the Vale. Two opposed causewayed entrances face almost due north and south. Cropmarks reveal:

- irregular lengths of ditch suggestive of segmented excavation;

- faint pits on the bank line, perhaps stone‑holes for an internal timber setting;

- a narrow double‑ditched feature running south‑north through the southern entrance—possibly an avenue or processional way. Surviving Earthworks today comprise a low, spread bank <0.3 m high and a shallow internal hollow; the southern arc is clipped by a modern field boundary.

Archaeological Evidence

The site was first recognised on RAF vertical air‑photos in 1946 and mapped in detail during the National Mapping Programme. Field‑walking in the 1980s recovered struck flint, including a leaf‑shaped arrowhead and several scrapers, hinting at Late Neolithic activity, but no controlled excavation has been undertaken. Its place within the Ure‑Swale ‘sacred vale’ suggests Cana Barn formed part of a planned monumental landscape conceived around 3000–2500 BC, broadly contemporary with Thornborough.

State of Preservation & Protection

Plough‑levelled for decades, Cana Barn survives primarily as a cropmark; earthworks are slight and best appreciated in low‑angle light or LiDAR imagery. Despite this, the ditch fills and any buried occupation layers remain largely undisturbed beneath cultivation soils. The monument was scheduled in 1994 (NHLE 1009790) and is monitored under agri‑environment agreements that promote minimal‑tillage regimes.

Visiting Advice

The henge lies on private farmland with no on‑site interpretation. It is best viewed from the public footpath that skirts Cana Barn farm (SE 361 717), where the low outer bank is just perceptible in favourable light.

Here is a summary of what we can see:

Liminal Spaces

“Liminal” comes from the Latin limen — “threshold.”

Anything liminal sits in‑between clearly defined states, places or identities: neither here nor there, but on the edge of becoming one or the other. The idea shows up in several disciplines, each with its own emphasis:

| Field | What “liminal” means | Classic examples | Why it matters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anthropology (Arnold van Gennep → Victor Turner) | The middle, ambiguous phase of a rite of passage — after separation from the old status, before reincorporation into the new. | Initiation ceremonies, coming‑of‑age rituals, pilgrimages. | In liminality normal rules suspend; participants are “betwixt and between,” open to transformation. |

| Psychology / Human experience | Moments or spaces where familiar cognitive frames drop away; we feel disoriented, nostalgic, uneasy, or inspired. | Empty airports at 3 a.m., hotel corridors, waiting rooms, a school hallway during summer break. | They highlight how much meaning we normally borrow from context; remove the context and the mind rushes to fill the gap. |

| Architecture / Urban studies | Transitional physical zones that mediate between public ↔ private, inside ↔ outside, past ↔ future. | Foyers, verandas, bridges, stairwells, plazas under flyovers. | Good design can soften or dramatize transitions, influencing flow, security, even social interaction. |

| Art & pop‑culture (“liminal space” aesthetics) | Images of eerily vacant, mundane places evoke a shared dreamlike mood (“the Backrooms,” vaporwave malls). | Photos of fluorescent, carpeted office cubicles; childhood play centres; foggy parking lots. | Online communities use them to explore nostalgia, uncanny valley feelings, and collective memory. |

Ambiguity & potential

Liminality isn’t a destination; it’s a state of flux. Rules loosen, identities blur, and creativity (or anxiety) spikes because the usual boundaries are missing.

Threshold effect

Crossing a threshold—literal or symbolic—signals that transformation is possible. Mythic gates, initiation huts, or a mundane elevator ride all mark a change of context.

Communitas

Turner observed that people sharing a liminal phase often experience a brief sense of egalitarian camaraderie—rank and hierarchy fade while everyone is “in the same boat.”

The uncanny

When a space designed for bustle is suddenly empty, or when day‑to‑day objects appear out of context, we feel the uncanny: familiar yet strangely foreign.

Why liminal thinking matters today

Design & placemaking – Architects deliberately craft thresholds (atriums, courtyards) to calm, prepare, or impress users as they shift modes (street → sanctuary, public → domestic).

Work & technology – Remote work erases many physical and temporal thresholds (commute, office lobby). People recreate them with rituals—closing the laptop, going for a walk—to mark “work mode off.”

Mental health – Therapeutic practice often places clients in controlled liminal states (retreats, vision quests, psychedelic sessions) where old narratives can be rewritten.

Cultural analysis – Periods of rapid social change (pandemics, political revolutions) are collective liminal phases. Norms soften, new possibilities open—and anxieties surge.

A quick way to spot a liminal space or moment

Ask: “Is this a place/time where one frame ends and another hasn’t quite begun?”

If yes—and especially if it feels strangely charged, empty, or timeless—you’re standing in a liminal zone.

Whether encountered in a deserted shopping centre after closing time, or in the pause between life chapters, liminality reminds us that meaning lives in transitions. Embrace the threshold, and you often find fresh vision on the other side.