Contents

- 1 Setting the scene for debate — defence, dwelling or ceremony?

- 2 The need for debate

- 3 Yeavering Bell – why this North-Northumbrian hillfort is a key test-case

- 4 Voices from each side of the modern discussion

- 5 Why start the case-study here

- 6 Yeavering Bell and the older ritual landscape – a clear-spoken overview

- 7 Key sources for further reading

- 8 Was Yeavering Bell built to face a real enemy?

- 9 What threat might the builders have had in mind?

- 10 But could the fort also have been ceremonial?

- 11 How that differs from Yeavering Bell

- 12 Take-away

- 13 An opposing viewpoint

- 14 A wall as theatre as much as shield

- 15 Working hypothesis

- 16 How we can test “continuity-of-ritual” at Yeavering Bell — step by step

- 17 A quick analogy: the stone axe becomes the iron sword

- 18 What this means for Yeavering Bell

“Looking north to Yeavering Bell – geograph.org.uk – 246376.jpg” by Stuart Meek is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

Setting the scene for debate — defence, dwelling or ceremony?

Over the last five years Iron-Age specialists have been re-examining what British hillforts were really for. The question is no longer just “fortress or farm?” but whether many of them were built first and foremost as places of gathering, display and ritual. Three factors have pushed the issue back onto conference programmes and journal pages:

- high-resolution LiDAR that shows elaborate entrances and viewing platforms which make little military sense;

- a run of large, open-area excavations (Caerau, Ham Hill, Broxmouth) revealing surprisingly thin domestic layers inside huge ramparts;

- a fresh look at ethnographic parallels where imposing Earthworks host ceremonial arenas rather than battles.

“Maiden Castle Iron Age Fort” by tudedude is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Two quotations capture the poles of the current argument.

Barry Cunliffe (defence-first, with settlement in mind):

“The forts provided defensive possibilities for the community at those times when the stress burst out into open warfare … Some were attacked and destroyed, but this was not the only, or even the most significant, factor in their construction.” (en.wikipedia.org)

Mark Bowden & Dave McOmish (ceremony-first):

“The idea that some hillforts performed ceremonial functions is not a new one … The morphology and topography of the ramparts themselves may indicate ceremonial activity.” (valeofleven.org.uk)

Between those positions sits a growing middle-ground view—championed by scholars such as Niall Sharples and Ian Armit—that hillforts could switch emphasis through time, sometimes housing households and livestock, sometimes staging seasonal assemblies, and sometimes offering real refuge when trouble loomed.

Photo by Giancarlo Revolledo on Unsplash

The need for debate

Personally, as a Mortimer Wheeler “fan-boy”, it took a lot to shift my boyish delight in the idea of all these forts, built by tribes that were forever fighting over something, as Julius Caesar and other Roman writers were keen to imply. However, the work I did trying to stop the ritual landscape of Thornborough had it’s affect, and as I opened myself to ideas of ritual and Henges, it struck me that many hillforts may well have been more like an evolution of henges, and other similar earthworks into a new Iron Age, which included a need for more elaborate structures, that may also serve as defence if needed, but this was, to me, increasingly seeming like a third design input, behind, tribal ritual, and acts of leadership.

The fact that so many of these forts were built in graveyards from the past, or had cursus or other Neolithic and Bronze Age monument inside them, or closely related to them. In addition, discoveries such as the Iron Age date for Castle Dykes Henge in Wensleydale adds fuel to this notion.

Similarly, such discoveries as the Arras style square Barrows at Thornborough, again shows, to my mind, a potentially very significant inter-tribal ritual act, which pays full attention to the henges and the wider ritual landscape. Not to mention the Iron Age pit alignments, one of which seems to travel directly to the Northern Henge.

“Inside the Celtic Iron Age hillfort of Tre’r Ceiri, Gwynedd Wales, with its 150 houses; finest in Europe 61” by Llywelyn2000 is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

Wider zones of control

Also, research based on wider geographies seems to show to me, that the Iron Age was one of regional, not, village locality based command and control. Tribes occupied and protected large swaths of land, and those hillforts that sit on tribal boundaries served to protect entire regions, not just the local village. So to me, increasingly, the notion of a local tribe building a fort to retreat to, when attacked, is really, far too simplistic, and assumes some kind of “cave-man” quality to our Iron Age ancestors that speaks, to me, more of a Christian/Roman need to see our ancestors as “thick” 🙂

I recently did a quick survey of Edinburgh, for example, and it seemed very likely that Edinburgh was a very old tribal capital, and it have a ring of forts demarking a much wider territory then the immediate surroundings of those forts and other structures.

Location over absolute best defence

From my perspective, I think it clear that some Iron Age forts, were never so, they had too many entrances, and whilst build on a steep hill, tended not to use that steep slop of the hill to it’s maximum advantage. i.e., many forts are built back from the edge to the hill, and that means, any “enemy”, can climb up the hill, catch their breath, and attack the fort from a much lower height difference. I personally think that this is a very important question, as it determines the types of questions archaeological investigators ask of these places in their research. We all know that it is too easy to “prove” a cognitive dissonance simply by only looking for evidence that supports the dissonant idea.

So I thought I would put my oar into the debate and suggest so ways that we could start trying to identify exactly what particularly types of forts were for.

Next steps in this could be to test the “ritual first” idea at a handful of case-study forts where the stratigraphy is well dated and domestic traces are minimal. For example, Yeavering Bell in Northumberland or Traprain Law in East Lothian comes to mind as good targets for that. So let us first take a look at Yeavering Bell.

“Yeavering Bell walk” by Pete Reed is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

Yeavering Bell – why this North-Northumbrian hillfort is a key test-case

Where and what it is

Yeavering Bell rises to 396 m in the northern Cheviots, overlooking the broad mouth of the River Glen near Kirknewton, Northumberland. On its twin-peaked summit sits the largest prehistoric hillfort in the county, enclosing about 5–6 hectares behind a massively built stone wall up to 3 m thick. Survey has mapped more than 120 round-house platforms inside the rampart, and a polygonal inner enclosure that seems to post-date the main occupation. (heritagegateway.org.uk, archaeologydataservice.ac.uk, doi.org)

Why it matters to the “ritual vs defence” debate

The fort combines some of the clearest defensive traits in Britain with a position that also proclaims power and identity.

Topography made for war – steep scree slopes guard three sides; the only original gateway lies on the gentler south saddle, funnelling any attacker up a long, exposed approach.

Stone rampart and vitrification – core‐drilling confirms deliberate burning of the wall, a phenomenon widely taken as evidence of siege or deliberate destruction.

Crowd capacity – the sheer number of house platforms suggests either a permanent community or, more likely, a place where hundreds of people (and their stock) could retreat in crisis.

Commanding visibility – the fort crowns the highest point for kilometres; even if it was primarily defensive, its silhouette would have projected the status of the Votadini (the Iron-Age tribe credited with its building).

Because Yeavering Bell scores high on every defensive metric, it is a useful counter-example when set alongside low-lying, multi-entranced enclosures that have been argued to serve mainly ceremonial purposes.

Voices from each side of the modern discussion

“Hillforts provided defensive possibilities for the community at those times when stress burst out into open warfare.” — Barry Cunliffe, Iron Age Communities in Britain (quoted widely) (en.wikipedia.org)

Yeavering Bell fits this view: strong walls, limited access, room for refuge.

“The ramparts and ditches around many hillforts were so complicated as to undermine any defensive function … a ceremonial role is a more likely explanation.” — Bowden & McOmish, “The Required Barrier” (1987) (researchgate.net)

Their critique works better at hillforts with multiple, theatrically in-turned entrances. At Yeavering Bell, the single gate and cliff-edge walls answer their objections, making it one of the few sites that even ritual-first scholars concede was purpose-built for real defence.

Why start the case-study here

- Clear defensive architecture lets us set a baseline for what a genuine stronghold looks like in northern Brigantia.

- Abundant internal platforms provide evidence to test refuge-versus-residence models.

- Later re-use – the early-medieval royal site of Ad Gefrin sits directly below, offering a chance to see how a defensive Iron-Age monument was re-read in post-Roman power politics.

“Maelmin Heritage Trail” by itmpa is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

Yeavering Bell and the older ritual landscape – a clear-spoken overview

A fort on a natural balcony above a ritual valley

Yeavering Bell stands at the south edge of the Milfield Basin, a wide, fertile floor that has the densest cluster of Neolithic henges in northern England. From the summit you can look straight down onto:

- Yeavering Henge – a 75-metre-wide earth ring tucked beside the River Glen, just 800 m south-east of the fort (Waddington 2005, pp. 67-71).

- Coupland and Milfield North/South henges – two to four kilometres downstream, forming a chain along an old river terrace (Harding 2013, chap. 9).

These monuments were built about 3000-2500 BC, two thousand years before the hillfort was started.

Bronze-Age cairns on the summit itself

Before any rampart encircled the peak, small stone cairns—probably Bronze-Age burial markers—were set on the natural crest. Excavations by Jobey (1965) found one Cairn partly sliced by the later Iron-Age wall. This shows the builders of the fort were aware of, and perhaps deliberately incorporated, an earlier sacred feature.

”

”

” by null is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Visual dialogue, not physical overlap

Unlike later medieval castles that often sit on top of churches or Roman forts, Yeavering Bell does not bulldoze the henges. Instead, it rises above them like a watching platform. Anyone visiting a ceremony in the valley would have seen the stone-walled rampart crowning the skyline. That commanding view may have been the point: the Iron-Age Votadini could project their authority over a landscape already loaded with ancestral meaning.

Continuity into the early medieval period

After the fort was long abandoned, the early-seventh-century royal settlement of Ad Gefrin (Hope-Taylor 1977) was planted on the valley floor, right beside Yeavering Henge and under the north slope of the hill. There Bishop Paulinus baptised King Edwin’s followers in AD 627. The site choice suggests that both the pagan henge and the Iron-Age hill-top still carried prestige that Northumbria’s new Christian rulers wished to tap.

Why Yeavering Bell is a good “defensive” control case

Despite sitting in this ritual landscape, the fort itself is textbook military:

- a single, easily-defended gate on the least-steep side;

- massive stone walls, some vitrified by intense heat (a sign of attack or deliberate firing);

- over a hundred round-house platforms that could shelter a large population in crisis.

Its builders may have saluted the older sacred valley below, but the hilltop enclosure was clearly designed to hold out against real enemies—a reminder that not every Iron-Age fort was primarily ceremonial.

Key sources for further reading

- Hope-Taylor, B. Yeavering: an Anglo-British centre of early Northumbria. HMSO, 1977.

- Waddington, C. Milfield Basin: Archaeology and Environment. Oxbow, 2005.

- Harding, J. Henges and Ring Monuments of the British Isles. Tempus, 2013.

- Jobey, G. “Excavations at Yeavering Bell.” Archaeologia Aeliana 4th ser. 43 (1965): 1–28.

Was Yeavering Bell built to face a real enemy?

A fort with ‘hard’ defensive gear

- Massive stone wall: up to 3 metres thick, built of rubble faced with large blocks.

- Single usable entrance: a narrow south-side gate reached by the only gentle slope; all other sides plunge down loose scree.

- Vitrified rampart stones: trenching on the west side has revealed blocks fused by extreme heat, the classic trace of a wall deliberately fired—usually during attack or a ritual destruction after occupation ended. (doi.org)

- Round-house crowding: more than a hundred platforms lie inside; that is far more than a family farm needs and matches the idea of a refuge that could hold many households and their stock in danger periods. (etheses.dur.ac.uk)

No arrowheads or slingshot caches have been found in the published excavations (Jobey 1965), so we cannot point to a known battle. But the deliberate burning of the wall and the costly stonework make it clear that the builders planned for genuine sieges, not just ceremony.

What threat might the builders have had in mind?

Rival Iron-Age communities: Classical geographers place the Votadini south-east of the Cheviots and the Selgovae just to the west. Ian Armit (2012) notes a chain of strongly walled hillforts running along Dere Street between the two zones, suggesting chronic low-level tension. Yeavering Bell sits on that same line overlooking the Glen valley route into the Milfield Basin. (doi.org)

Control of stock and pasture: The summit commands the best summer grazing in north Northumberland. A fort that can be seen for kilometres is a statement of ownership—and a secure pen if raiding parties appear.

Late-Iron-Age instability just before Rome: Coin finds from Traprain Law and Eildon Seat imply vigorous cross-border movement in the first centuries BC/AD. A large, stone-walled fort would offer insurance while power blocs shifted.

“Hill of Tara IR – Cnoc na Teamhrach” by Daniel Mennerich is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

But could the fort also have been ceremonial?

Possibly—but the evidence is weaker than at sites built for ceremony, such as the Hill of Tara.

View of older sacred places: Yeavering Bell rises directly above Yeavering Henge and its neighbouring henges. That sight-line might have been meaningful, yet the fort does not encroach on the valley monuments; it towers over them.

Bronze-Age cairns on the summit: at least two earlier cairns underlie the rampart, so the peak already held ancestral echoes.

No built platforms or entrance forecourts: forts argued to be “ritual first” (for example Hambledon Hill in Dorset) often have wide funnel entrances and meeting terraces; Yeavering’s single tight gateway and sheer flanks look purely tactical.

Contrast with the Hill of Tara (Co. Meath)

Tara’s main Earthwork, the Ráth na Ríogh, has broad gaps, gently sloping banks and internal Ritual Mounds (the Mound of the Hostages, the LIA Fáil stone). Nothing about it would halt an army for five minutes. Tara’s earthworks frame assemblies and inauguration rites; Yeavering Bell’s walls are built to keep enemies out.

Working conclusion

Yeavering Bell stands out in the Cheviots as a fortress first:

- Its builders spent huge labour on a stone wall and chose the steepest summit in sight.

- The only certain violent trace is the vitrified wall—proof that someone set the defences ablaze, whether attacker or abandoner.

- While the valley below remained an important ceremonial arena right into the early medieval period, the peak above was almost certainly picked for security, surveillance and statement power rather than for hosting gatherings.

Future excavation that samples the house-platform interiors or the gate passage may yet uncover weapons or slingstones, but—on present evidence—Yeavering Bell is best read as the hard-edged military counterpoint to the softer ritual landscape spread out beneath it.

“Rath of the Synods” by Stefan Jürgensen is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Enter the Raths

However, a wider look shows the Hill of Tara does not sit in splendid isolation. A belt of smaller earthworks –Rath Lugh, Rath Maeve and scores of early-medieval ringforts (known in Irish as ráth or lios) – forms a loose halo two to five kilometres out from the royal enclosure. These are true defended homesteads: circular banks and ditches about 25–50 metres across, once topped by a timber palisade and intended to keep stock in and raiders out. Some of them, notably Rath Maeve on the western ridge, were large enough to muster armed retainers for Tara’s ceremonies.

That defensive cordon is one reason Tara’s own summit earthworks could remain almost theatrical in design: when a king convened an inauguration or an óenach (fair) on the hill-top, his followers were already quartered – and his flanks already guarded – in the ringfort belt below.

How that differs from Yeavering Bell

- Single peak versus dispersed network

Yeavering Bell is itself the defensive hub; there is no known ring-fort necklace on the surrounding slopes. If the Votadini wanted cover, livestock pens and look-outs, they put them all inside the big stone wall on the summit. However, we need to take care to not expect an exact similarity in design or purpose between the two locations. The is a need for a wider review of the tribal area that Yeavering served. - Scale and date

The Irish ringforts around Tara belong mainly to the 6th–9th centuries AD, long after the large Iron-Age rampart on Yeavering Bell had gone out of use. They are also far smaller – farmsteads, not hillforts. - Ceremony kept low versus high

At Tara, public ritual happens inside the ring-fort-protected hollow on the crest of the ridge, while the practical defence lies further out. At Yeavering, the ritual focus (Yeavering Henge and, later, the Anglo-Saxon royal hall and baptismal site of Ad Gefrin) stays on the valley floor; the hill-top is reserved for the stronghold.

Take-away

Yes, Tara’s ritual core is shielded by a scatter of ringforts, but that pattern belongs to the early-medieval period and to the Irish farming landscape. In Iron-Age north-east England the Votadini solved the same security problem in a different way: they put one massive wall around a single summit and looked down on the ceremonial plain below.

An opposing viewpoint

At this point, I’d like to turn this debate on it’s head, and suggest that we have been ignoring a great deal of evidence of ritual practice, when thinking of the Iron Age people.

Archaeologists have tended to start with the question “how well could this place fight?” instead of “why did people think this place mattered?” In doing so we risk pushing a long ritual history into the background and treating later walls as the reason for the site, when in fact they may be an after-layer added to protect – or proclaim – something older and sacred.

Below is a way to re-frame Yeavering Bell that keeps the ritual landscape at centre stage while still noticing the stone wall defences of the fort:

A sacred valley first

The Milfield Basin is thick with Neolithic henges and Bronze-Age cairns. Those circular earthworks are not random: they line the river terrace as if staking out a processional way. Long before anyone hauled stone up Yeavering Bell, people already treated this valley as special ground.

The hill chosen for its outlook, not its slope

Stand on the summit and the henges lie almost like beads on a string below you. The wall encloses both peaks, but the single gate points directly toward the valley floor – as though the builders wanted a controlled, framed view down to the ritual arena. That orientation makes just as much sense for ceremony and display as for defence.

A wall as theatre as much as shield

Yes, the rampart is massive and the entrance tight; that can deter enemies. But a huge stone circuit also turns the hill into a kind of open-air stage-set. When people gathered for midsummer at the henge, the ring of masonry glowing on the skyline would have dramatized the event and, at the same time, marked out who owned the high ground.

Continuity into early Christianity

When Bishop Paulinus set up his baptismal pool beside Yeavering Henge in 627 AD, he – or more likely his local advisers – chose a spot already freighted with meaning. Early missionaries often did that, baptising in “pagan” rivers and re-naming local gods as saints. The iron-age wall on the summit needed no new use; its looming presence simply underlined the authority of the rite below.

Absence of battle evidence cuts both ways

We have a vitrified section of wall – that proves intense fire, but it doesn’t prove an assault; ritual “closing” fires are just as possible. We lack arrow-heads, sling-stones or mass graves. Until they appear, wall-thickness alone is not enough to call Yeavering Bell a fortress “built because of war”. It could just as well be a sacred enclosure given monumental strength.

Working hypothesis

Yeavering Bell began as the high-altar to a valley of sanctuaries.

Its later stone defences served to frame, protect and proclaim that ancient holy ground, not only to keep out an unnamed enemy but to demonstrate, in stone, who controlled the rites performed below. The wall is therefore an addition to ritual continuity, not proof that ceremony stopped.

How we can test “continuity-of-ritual” at Yeavering Bell — step by step

- Map the finds by context, not by modern categories.

Where an object lies tells us why it may have been placed. If a sword turns up jammed upright in a rampart gap or buried under a round-house floor, that looks like deliberate offering, not a dropped weapon.- What we have so far at Yeavering Bell is thin: a handful of rotary-quern fragments, a small bronze brooch, two or three iron blades (Jobey 1965, 12-15). We need a new gridded metal-detector and soil-chemistry survey to see whether a pattern of “special places” emerges, particularly around the gate and the inner enclosure.

- Compare “special finds” with known ritual hoards.

Bronze Age people buried polished axes in rivers; Iron-Age people bent swords and spears before sinking them in lakes (Llyn Cerrig Bach; Hallstatt; South Cadbury rampart deposits). If the Yeavering material shows the same bending, burning or careful hiding, that points to ritual action continuing into the Iron Age. - Look for signs of forced entry or crisis layers.

A truly besieged fort usually leaves arrowheads in the entrances, sling-shot piles on the walls, or a burn-layer full of roof-daub and broken crockery inside the houses (Danebury, Ham Hill, Castle Dore). Yeavering Bell so far shows vitrified wall-stone but no battle rubbish. Vitrification can equally be an abandonment rite: walls burnt to seal the site when its owners moved away. Scientific work on the heat-altered rock (magnetic susceptibility, thin-section) can tell us whether burning was localised and controlled—common in ritual “closing”—or widespread and chaotic—more likely in attack. - Cross-reference with the valley ritual sequence.

The henge at Yeavering has Late Bronze-Age animal-bone deposits and Iron-Age pits dug beside the bank (Waddington 2005). If the hill-top finds and the valley finds share artefact styles or radiocarbon ranges, that supports the idea that both places stayed ritually linked. - Strip away Roman spin.

Julius Caesar, Tacitus and Dio called northern peoples war-mad, but they were writing propaganda for Roman audiences. We balance their words against what the ground says. Absence of mass-grave trauma, plus careful deposition of “weapons,” undercuts the picture of a hill constantly at war.

A quick analogy: the stone axe becomes the iron sword

- 2500 BC – a polished jade axe from the Alps is buried in a Dorset Barrow: no one expects to chop wood with it.

- 800 BC – bronze leaf-shaped swords go into the River Thames, bent double.

- 100 BC – iron swords are burnt, broken and buried at sites like Danebury.

Different materials, same behaviour: offer a high-status object to a powerful place.

If Yeavering’s iron blades were heat-treated, snapped or buried under floor posts, that is continuity of practice, not evidence of combat.

What this means for Yeavering Bell

The stone wall could still be a genuine fortification, but its first role may have been to frame and guard ceremonies already anchored in the valley. Until we have artefact patterns that scream “battle debris,” a cautious reading is:

- Ritual first – defence added because sacred ground is worth guarding.

- Later Christian rites (Paulinus) follow the same valley-hill dialogue, re-energising the place rather than replacing it.

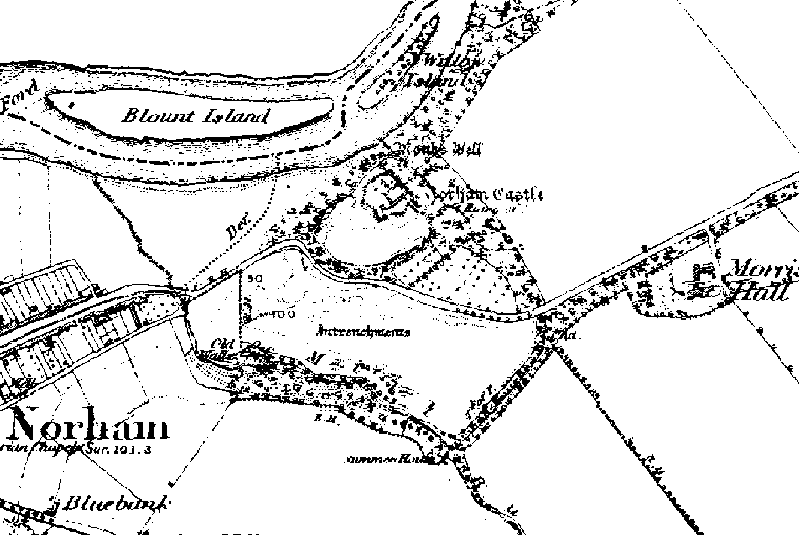

Yeavering Bell Finds Distribution

Here is a schematic plan to show where the main features and find-spots lie on Yeavering Bell:

- dashed black line — stone rampart

- blue polygon — small inner enclosure near the higher summit

- brown Xs — two Bronze-Age cairns incorporated into the rampart line

- red X — the only original entrance (south gate)

- orange X — stretch of vitrified wall on the west side

- green X — spot where Jobey (1965) recorded two iron blades

- purple X — find-spot of the small bronze brooch

- grey dots — some of the round-house platforms scattered inside

Positions are approximate, based on Jobey’s site plan and the National Monuments Record grid; the drawing is meant to help orientation rather than replace a surveyed map.

This layout makes two things clear:

- Weapons and brooch both lie well inside the wall, not in the gateway or on the rampart, supporting the idea that they were placed (or lost) during peaceful use of the interior rather than during a fight.

- The vitrified sector is localised—it does not ring the whole fort—consistent with a deliberate burning event focused on one stretch of wall.

I’m going to end this first part of my contribution to this debate. Clearly, there are many other areas to look into, and I won’t eat this elephant in one bite.