Egglestone Abbey, nestled on the southern bank of the River Tees, is a testament to the spiritual and architectural endeavours of the Premonstratensian canons. Founded between 1195 and 1198 by the de Moulton family, the abbey was established during a period of monastic expansion in England.

Egglestone Abbey, nestled on the southern bank of the River Tees, is a testament to the spiritual and architectural endeavours of the Premonstratensian canons. Founded between 1195 and 1198 by the de Moulton family, the abbey was established during a period of monastic expansion in England.

The Premonstratensians

The Premonstratensians, emerging in the early 12th century, represent a unique blend of monastic traditions and clerical duties. Founded by St. Norbert of Xanten in Prémontré, France, this order of canons regular adopted the Rule of St. Augustine but infused it with the rigorous asceticism reminiscent of the Cistercian way of life.

The White Canons, as they were colloquially known due to their distinctive white habits, sought to harmonize the contemplative life with active ministry, thus bridging the gap between the cloistered devotion of monks and the pastoral engagement of secular clergy.

Tribulations

Egglestone Abbey was not immune to the tribulations of the time. The abbey frequently faced financial hardships, exacerbated by its proximity to the volatile English-Scottish border. This led to repeated devastation during cross-border conflicts, particularly during the Scottish raids in 1315.

The raids of 1315 were a continuation of the First War of Scottish Independence, a conflict that arose from a series of events following the death of Alexander III of Scotland in 1286 and his granddaughter Margaret, Maid of Norway in 1290. The lack of a clear heir led to a power vacuum, with thirteen claimants to the Scottish throne. The nobles of Scotland sought the arbitration of Edward I of England, who asserted his lordship over Scotland in the process. His imposition of John Balliol as king did not sit well with other claimants, leading to Balliol's eventual deposition and the Scots' alliance with France against England.

Edward I's military campaigns into Scotland began in 1296, marking the start of the war. Despite initial English successes and the capture of significant figures like William Wallace, the Scots continued to resist. The tide turned with the rise of Robert the Bruce, who was crowned King of Scotland in 1306. His leadership culminated in the pivotal Battle of Bannockburn in 1314, where the Scottish forces defeated Edward II of England, significantly boosting Scottish morale and unity.

The raids into Northern England, including those in 1315, were part of a strategy by Robert the Bruce to apply pressure on England and to assert Scottish sovereignty over contested border areas. The Siege of Carlisle in July 1315, although unsuccessful for the Scots, was one of the most notable events of these raids. The Scottish forces, lacking the means to sustain a prolonged siege, withdrew, but their actions underscored the ongoing conflict and the volatility of the Anglo-Scottish border during this period.

Architecture

Architecture

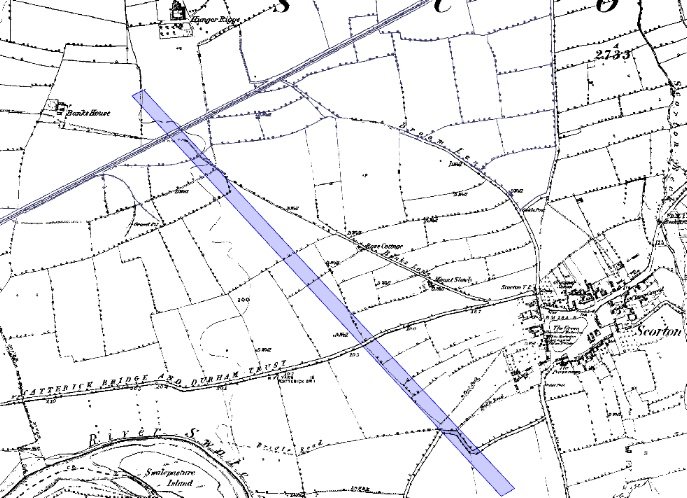

The abbey's architecture reflects its history of economic struggle. Unlike wealthier institutions, the buildings of Egglestone Abbey were modest, with the church itself being unusually situated on the south side of the cloister.

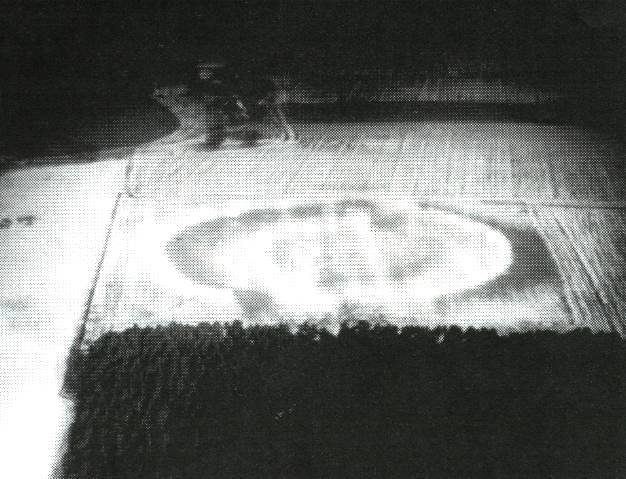

The architecture of Egglestone Abbey is a fascinating blend of austerity and adaptation, reflecting the monastic community's resilience and resourcefulness. The abbey's church, unusually positioned on the south side of the cloister, was initially built around 1200 and was modest in scale. However, it underwent significant expansion in the mid-13th century, likely to accommodate an increasing number of canons and the altars needed for their liturgical duties. This expansion included the construction of a larger presbytery and broad transepts, which were indicative of the abbey's evolving needs and spiritual commitments.

One of the most distinctive features of Egglestone Abbey's architecture is the great eastern window in the presbytery, which stands out for its lack of tracery, consisting instead of four tall mullions that allow light to flood into the space. This unique design choice may have been influenced by the abbey's limited resources, as tracery is typically more elaborate and costly to produce. The nave of the church also presents an unconventional aspect; it was widened southwards, breaking from the traditional alignment and symmetry often seen in ecclesiastical buildings of the period.

The east range of the abbey, adjacent to the church, housed the chapterhouse and the monks' dormitory on the first floor. The chapterhouse was where the canons would gather daily to discuss the business of the abbey and read a chapter from the Rule of St. Augustine. The dormitory, now mostly lost to time, would have been a communal sleeping area for the canons, emphasizing the communal living that was central to their way of life.

The north range, built slightly later than the east, included the refectory on the first floor and the warming house below. The refectory, where the canons took their meals, was an essential part of monastic life, emphasizing the importance of communal dining as a form of fellowship and reflection. The warming house was one of the few places in the abbey where a fire was allowed, providing a space for the canons to warm themselves during the cold months.

The abbey's church, with its great eastern window of five lights, is particularly noteworthy for its four tall mullions that stand without any tracery, a rare design choice that may reflect both aesthetic preference and economic necessity. The nave, originally narrow and occupying only two-thirds the length of the cloister, was later widened southwards, demonstrating a pragmatic approach to expansion and use of space.

The abbey's church, with its great eastern window of five lights, is particularly noteworthy for its four tall mullions that stand without any tracery, a rare design choice that may reflect both aesthetic preference and economic necessity. The nave, originally narrow and occupying only two-thirds the length of the cloister, was later widened southwards, demonstrating a pragmatic approach to expansion and use of space.

The east range of the abbey, which once housed the chapterhouse and the monks' dormitory, has largely been lost to time, but its layout still hints at the daily routines of the canons. The chapterhouse, where the canons convened to discuss abbey matters and read from the Rule of St. Augustine, would have been a centre of governance and spiritual reflection. Above, the dormitory provided communal living quarters, reinforcing the collective ethos of the Premonstratensian order.

Adjacent to the chapterhouse, the remains of a vaulted undercroft suggest the presence of storage or workspaces, essential for the self-sufficient lifestyle of the canons. A room above this undercroft, adjoining the garderobe or latrine, indicates the practical considerations considered in the abbey's design. The north range, built slightly later than the east, included the refectory on the first floor over the warming house, where the canons could find respite from the cold.

The abbey's conversion into a mansion and later into farmworkers' dwellings after the Dissolution of the Monasteries led to the loss of many monastic features. However, the surviving structures, such as the black stone table-tomb of Sir Ralph Bowes in the church crossing, provide a poignant connection to the past. The tomb, though missing its top, along with other tomb slabs evident on site, speaks to the abbey's role as a place of burial and memory.

The abbey's conversion into a mansion and later into farmworkers' dwellings after the Dissolution of the Monasteries led to the loss of many monastic features. However, the surviving structures, such as the black stone table-tomb of Sir Ralph Bowes in the church crossing, provide a poignant connection to the past. The tomb, though missing its top, along with other tomb slabs evident on site, speaks to the abbey's role as a place of burial and memory.

The Dissolution of the Monasteries under King Henry VIII marked the end of Egglestone Abbey as a religious institution. In 1548, the site was granted to Robert Strelley, who converted parts of the abbey into a mansion. Over the centuries, the abbey fell into disrepair, with some of its stones repurposed for other constructions, such as the paving of the stable yard at Rokeby Park. It wasn't until the 20th century that the ruins were placed under state guardianship, ensuring their Preservation.

Today, visitors to Egglestone Abbey can explore the remnants of this once-thriving monastic community. The site, managed by English Heritage, offers a glimpse into the daily lives of the White Canons, with the chapterhouse, dormitory, and refectory ruins providing a tangible connection to the past.