Contents

- 1 Nathwaite Bridge river crossing points

- 2 Do two neighbouring fords make sense on the River Cover?

- 3 Bottom line

- 4 Questions regarding the age of Nathwaite Bridge

- 5 Could Nathwaite have hosted an earlier bridge?

- 6 Why a bridge here makes historical sense

- 7 What would prove (or disprove) an earlier bridge?

- 8 Precedents elsewhere in the Dales

- 9 Working conclusion

Nathwaite Bridge from the West Scrafton side

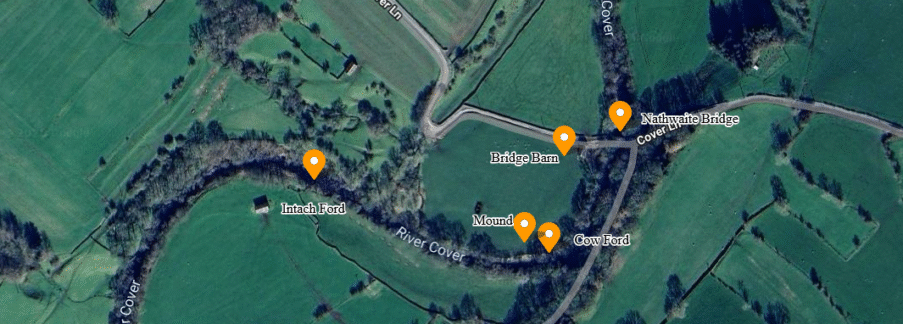

Nathwaite Bridge river crossing points

Nathwaite Bridge, over the river Cover in Coverdale, is just about the only way any heavy traffic can easily cross between the key villages of Carlton and West Scrafton. The importance of the location is perhaps underlined as the last place down the river Cover where it remains reasonably ford-able, and therefore crossable in past times when no closer bridge existed.

The purpose of this article is to expand on this observation, and understand more about how this location was used in past times, as we try to shed some light on Coverdale’s past.

Cow Ford |

Nathwaite Bridge |

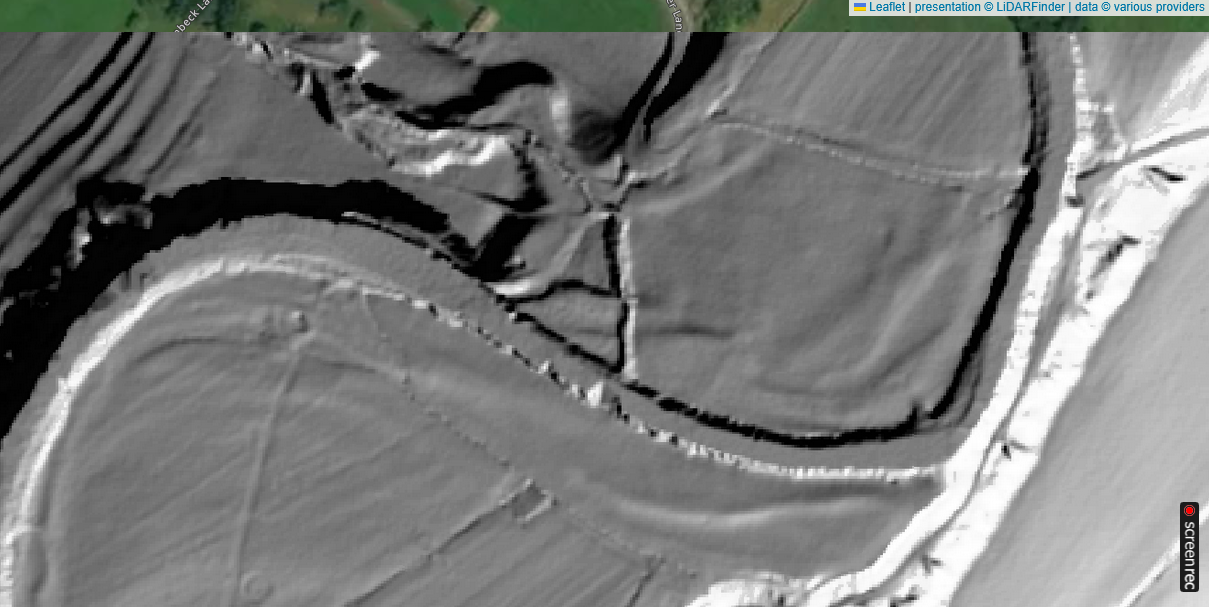

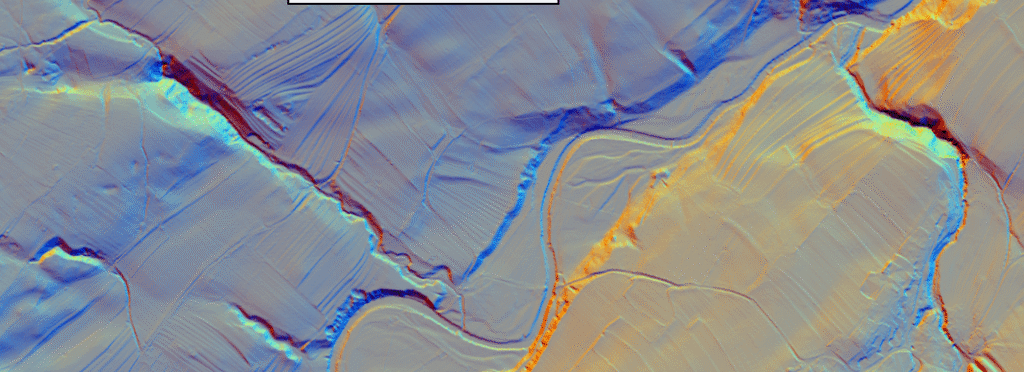

Fords and River crossings at Nathwaite Bridge Coverdale – LiDARFinder |

Do two neighbouring fords make sense on the River Cover?

On a small, fast-rising moorland river such as the Cover, usable fords are rare, seasonal and highly localised. Having two riffle-crossings within a single hay-meadow actually follows the logic of dale hydrology and land-use.

| Hydrological factor | Coverdale reality | Consequence for ford siting |

|---|---|---|

| Bedrock & riffle formation | The Cover cuts down through gently dipping Yoredale limestones and Shales. Where a tough Grit or Limestone band outcrops, the river develops a shallow “riffle” with a stony pavement only 10–30 cm deep in moderate flow. | Fords can be opened only where such natural steps occur; in the kilometre around Nathwaite Bridge there are just two continuous Limestone pavements, hence two viable fords. |

| Flash-flood regime | Winter Spate flows (> 25 m³ s⁻¹) after snow-melt or frontal rain make the river waist-deep and unfordable for days. Base-flow in late spring–summer drops below 1 m³ s⁻¹, exposing the riffles. | Fording season naturally shrinks to late April – early November in an average year. Once frosts return, cattle are yarded and coal is sledged or carted over the bridge instead. |

| Flood-plain topography | The north bank carries a relict terrace; south bank meadows are flatter and liable to winter inundation. A ford must start and end on ground high enough to stay above moderate Spates. | Only the two riffles near Bridge Barn have compatible landing slopes on both banks; elsewhere, steep or marshy banks prohibit exit. |

| Human routing logic | Medieval Pack-horse routes aimed for the straightest line up-dale, accepting a seasonal ford rather than detouring for a bridge. Once a masonry bridge was funded (late 18th c.), carts used it year-round, but the fords still served livestock and, briefly, mining spoil-carts (upper ford). | The coexistence of a bridge and two “legacy” fords reflects different traffic classes and seasons, rather than redundant duplication. |

River Crossings at Nathwaite Bridge. LiDAR image showing wider area. – National Library of Scotland

Seasonality in practice

- Pack-horse era (pre-c. 1800) – Coal or wool trains timed river crossings for late spring through early autumn; in winter the same goods were sledged along frost-hardened field lanes or stored until levels fell.

- Bridge era (post-1800) – Wheeled lime, coal and produce carts concentrated on Nathwaite Bridge, but stock still used the fords when drifting between intakes or when a swollen beck made the bridge approaches boggy.

Nathwaite Bridge – Wider Satellite view – Google Maps

Why no more fords upstream or downstream?

- Upstream, the valley narrows, and bedrock steps are buried beneath deeper pools—no suitable pavement for fording until Arkleside (4 km west).

- Downstream, the Cover enters confined, limestone-gorge sections where banks are 3–4 m high; the next natural crossing is Cover Bridge (mason-arch, 17th c.).

Bottom line

In upland dales, a ford is a singular hydrological gift—a shallow, stony riffle aligned with firm banks on both sides. If two such spots lie within the same meadow, people will exploit both: one may specialise for livestock or ad-hoc industrial haulage (the “cow ford”), the other evolve into a permanent bridge once year-round wheeled traffic demands it. Outside those sweet-spots the Cover is either too deep, too fast, or bordered by soft alluvium, explaining the long gap to the next crossing upstream or downstream.

Questions regarding the age of Nathwaite Bridge

|

|

|

In regard to Nathwaite bridge, we have visited it, and can see the site is quite complex, with signs of earlier construction, some of which seems to be older than the current build date for the bridge. That needs to be proven, of course. But, given the seasonality of fords, there is still the possibility of an earlier, now forgotten bridge here. Given the presumed need for communications between Carlton and West Scrafton, it makes sense that there would be at least one permanent river crossing between the two villages.

|

|

|

Could Nathwaite have hosted an earlier bridge?

Everything we can see on the ground—and what is not on the early maps—keeps that option alive:

| Field observation (2025 visit) | What it may mean |

|---|---|

| A second masonry footing 0.8 m upstream of the present arch, built of roughly tooled blocks markedly darker than the main bridge fabric. | Could be the south-west abutment of an earlier span robbed for stone when the extant bridge went up c. 1790–1800. Its coursing and tooling look more 17th-century than late-Georgian. |

| A flat, rubble-packed causeway (now grassed) leading from the north bank directly to that footing, not to the modern arch. | Suggests a historic approach road on a slightly different line—more consistent with pack-horse or footbridge alignment. |

| Rounded orthostats lying in the riverbed 3–4 m downstream. | These water-worn slabs could be the kerb stones of a timber trestle or clapper bridge that collapsed and was swept just downstream. |

| No obvious full-height wing walls on the modern bridge; instead a butt-return of older fabric keyed in behind the later parapet. | Builders of the late-Georgian bridge may have tied into an existing medieval/post-medieval abutment rather than starting from scratch. |

Why a bridge here makes historical sense

- Cross-dale traffic nexus – Carlton (monastic grange, later Bolton Abbey estate centre) and West Scrafton (copyhold township) exchanged stock, cheese and coal daily. A permanent crossing would shorten the 5 km detour via Cover Bridge.

- Seasonal unreliability of fords – The Cover’s winter spates regularly exceed 0.8 m depth; anything more than knee-deep is unsafe for laden pack animals. Medieval estate accounts for many Yorkshire dales show timber footbridges erected on primary routes decades—even centuries—before stone arches were affordable.

- Parish boundary quirks – The field south of Nathwaite is in Carlton township; just across the bridge you are already in West Scrafton. Parish vestry minutes often note joint responsibility for “wood briggs” at township boundaries—exactly what might once have stood here.

What would prove (or disprove) an earlier bridge?

| Line of enquiry | Specific steps |

|---|---|

| Archival |

|

| Map regression |

|

| Fabric analysis |

|

| Sub-surface survey |

|

| Place-name & field-name evidence |

|

Precedents elsewhere in the Dales

| Lost timber bridge, later replaced by stone | Documentary & field evidence |

|---|---|

| Crackpot Footbridge (Swaledale) | Lease of 1601 mentions “wood brigge” at Rake’s Dyke ford; stone arch built 1814; LiDAR revealed embanked track to earlier footing. |

| Kettlewell Upper Bridge (Wharfedale) | 1625 verdict for sharing repair of “woode brig”; OS 1st-ed shows stone arch (still standing); downstream spoil reveals oak sill beam tree-ring dated to 1582 ± 10 yrs. |

These parallels strengthen the hypothesis that Nathwaite once hosted a timber foot- or pack-bridge, later upgraded when estate and Turnpike capital converged in the late 18th century.

Working conclusion

- Yes, a forgotten bridge is plausible: the non-aligned causeway, older masonry fabric and seasonal logic all point toward an earlier timber structure.

- Proving it will require a blend of map regression, archival trawl, mortar dating, dendrochronology and sub-river probing—feasible, low-budget techniques that have paid off elsewhere in the Dales.

- Whatever the result, that enquiry will refine your traffic-flow model and help explain why two seasonal fords and a late-Georgian arch coexist within a single hay-meadow bend of the River Cover.