Dunagoil Hillfort

Dunagoil Hillfort, (Isle of Bute, Argyll & Bute)

Introduction

Geography

Dunagoil crowns a 30 m-high columnar-basalt promontory on the south-west coast of Bute, overlooking the Sound of Bute and the Cumbraes. Cliffs on the north and west form natural ramparts; only the gentle ESE saddle gives easy access. The oval summit plateau measures c. 110 × 45 m and commands wide sea-lane views, hinting that maritime traffic as well as land routes were monitored from the fort. The underlying dolerite/basalt sill, is crucial: when fired it melts readily into dark green-black glass, explaining why Dunagoil is one of the most spectacularly vitrified forts in Britain. (Canmore, hillforts.arch.ox.ac.uk)

History & Chronology

Artefact typology anchors the main occupation in the Late Iron Age (≈ 400–200 BC): finds include La Tène 1c iron brooches, rotary quern fragments and decorated bone pins. Earlier activity is attested by a Bronze-Age clay spear-butt mould and polished stone axes, while scattered flints hint at even earlier use of the headland. No radiocarbon or archaeomagnetic dates have yet been published, so the precise firing episode remains to be fixed. (Canmore, butemuseum.org.uk)

Archaeology

A single timber-laced curtain wall, about 3.6 m thick, encloses the summit; on the south-west side its rubble core has fused into a continuous slag sheet several decimetres thick, confirming thorough vitrification. Beam-socket voids and charcoal lenses show where the wooden lacing once ran. Adjacent knolls carry a smaller enceinte (“Little Dunagoil”) and a cliff-edge outwork, implying a multiphase defensive scheme. Excavation milestones include Ludovic Mann’s 1913–19 trenches, RCAHMS’s 1942 emergency survey, and a full EDM/plane-table survey by the University of Edinburgh in 1994–95; all records reside with Canmore and Bute Museum. (Canmore, Britain Express)

Heritage & Access

Dunagoil is a Scheduled Monument (SM90017) managed by Historic Environment Scotland. The crag lies in open pasture, reached by footpath from Dunagoil Bay car-park; visitors can examine glassy basalt blocks in situ (caution: the vitrified faces are slick when wet). Artefacts are displayed in the Bute Museum, Rothesay, which interprets the site within Bute’s wider prehistoric landscape. Dunagoil’s dramatic vitrification, rich multi-period finds and commanding coastal position make it a cornerstone for studies of Iron-Age polities and the technology—and symbolism—of rampart melting in Atlantic Scotland. (butemuseum.org.uk)The Dunagoil Story – unfolding a century of investigation

Below is a narrative that traces how our understanding of the vitrified fort on the Isle of Bute has evolved, stage by stage, as fresh techniques and questions were brought to bear. It deliberately avoids any mention of contemporary projects so that it can be dropped straight into a public “site page”.Location in brief

Perched on a basalt ridge above Dunagoil Bay (NGR NS 0847 5312), the fort commands both the coastal route up the Firth of Clyde and the over-land pass to St Blane’s. A single timber-laced wall (≈ 3.6 m thick) encloses an oblong summit 85 × 20 m; its core is fused into green-black glass over much of the south side. (Atlas of Hillforts)

Dunagoil Hillfort - Roy Highland Map 1752 - National Library of Scotland

Chronicle of enquiry

| Phase | Who / what was done | How this changed the picture |

|---|---|---|

| 1780–1890s: estate plans & antiquarian sketches | 1780 estate map, Ross (1880) & Hewison (1893) publish descriptions. | First recognition of artificial rampart and cliff-edge gaps; no real attempt to date or explain vitrification. (Atlas of Hillforts) |

| 1914 – 1919: Marshall & Mann excavations | John Marshall and Ludovic Mann cut trenches through wall and summit midden over three campaigns. | Confirmed timber lacing + vitrification, recovered a remarkably rich artefact suite (ring-headed pins, La Tène I-style brooch, crucibles, moulds, faunal and shell midden). These finds later underpinned the “Dunagoil series” typology of ring-headed pins and suggested metal-working on site. (Atlas of Hillforts, Canmore) |

| 1943: RCAHMS Wartime Emergency Survey | Rapid wartime record photographs and dimensioned sketch. | Provided the base-line archive used by later researchers; highlighted erosion of wall faces. (Atlas of Hillforts) |

| 1958 – 61: Little Dunagoil training dig & cave work | Dorothy Marshall led Glasgow University students in the neighbouring “Little Dunagoil” enclosure and the two occupation caves. | Demonstrated continuous activity from Late Bronze Age to medieval period in the wider complex, showing the vitrified fort sat within a multi-period landscape. (Historic Environment Scotland, wosas.net) |

| 1960s – 70s: scientific turn | Helen Nisbet’s geological sampling (1974–75) and photographs; OS field visit (1976). | Petrographic work linked the glass to local basalt and proved in-situ burning; moved debate from “lightning strike” folklore to deliberate high-temperature firing. (Atlas of Hillforts) |

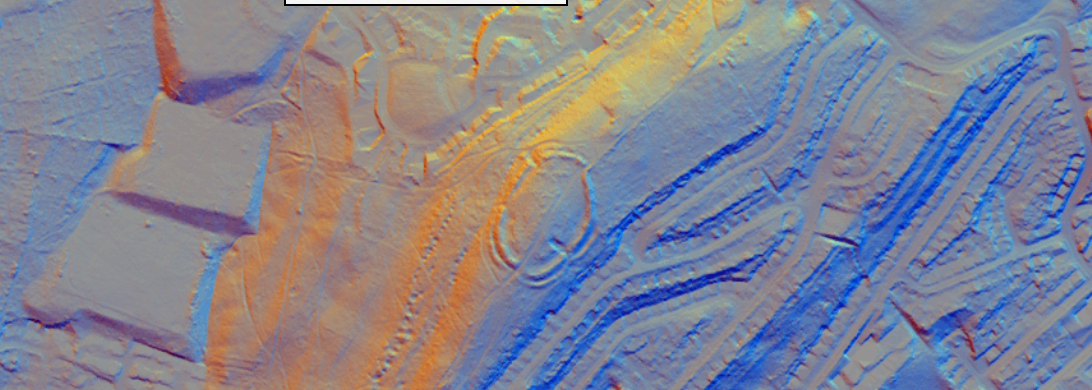

| 1994 – 95: Edinburgh University analytical survey | Harding, Ralston & Burgess produced EDM plans, terrain model and assessed stonework. | Proposed an outer ‘bailey’ incorporating the adjacent ridge, implying a two-phase expansion; pushed scholars to view Dunagoil as a potential high-status citadel. (Atlas of Hillforts) |

| 2004: Harding’s re-assessment | Paper in Trans. Buteshire NHS re-examined earlier trenches & topography. | Suggested re-interpretation of the NE terrace and emphasised reuse of vitrified rubble in secondary defences. (Canmore) |

| 2009 – 10: RCAHMS re-survey | High-resolution GPS and Photogrammetry; contested the ‘bailey’ hypothesis, arguing outer walls are later agrarian. | Opened a live debate on the fort’s true extent and sequence, illustrating the value of revisiting legacy interpretations with new data capture methods. (Atlas of Hillforts) |

| 2010s – 2020s: laboratory & modelling studies | Samples from Dunagoil feature in mineralogical, thermoluminescence and micro-CT studies on vitrification processes (e.g. Dolan 2020 PhD). | The fort now serves as a reference set for experimental firing trials and archaeomagnetic calibration, anchoring wider Scottish research into why and how ramparts were turned to glass. (DSpace Stirling, DSpace Stirling) |

Dunagoil Hillfort - Satellite - National Library of Scotland |

Dunagoil Hillfort - OS Series 1 - National Library of Scotland |

From curiosity to type-site – why Dunagoil matters in research practice

- Artefact typologies – The ring-headed pins and glass bangles recovered by Mann are so characteristic that they lend the site’s name to an entire subgroup in Iron-Age metalwork catalogues. (Canmore)

- Vitrification science – Nisbet’s bedrock studies first proved that wall-stone melted in place; modern micro-analyses continue to use Dunagoil slag to model phase changes at 1 100 – 1 200 °C. (Atlas of Hillforts, DSpace Stirling)

- Training ground – From the 1950s student digs to 1990s total-station work, Dunagoil has been a favourite ‘classroom’ because the vitrified wall, caves, middens and later farmsteads illustrate excavation, survey and palaeoenvironmental methods all within 300 m.

- Debate test-bed – Conflicting readings of the NE terrace exemplify how fresh datasets (GPS models, LiDAR) can overturn surveys barely a decade old, making the fort a live case study in interpretative caution. (Atlas of Hillforts)

Current consensus and gaps

- Date-range – Artefacts point to primary occupation in the mid-Iron Age (c. 400 BCE – 100 CE) with later reuse, but absolute dating (radiocarbon/archaeomagnetic) is still missing.

- Purpose of vitrification – Laboratory melting demonstrates controlled, prolonged firing, but whether this was a display of power, a construction technique or ritualised destruction remains unresolved.

- Outer works – The extent of any secondary enclosure is disputed; high-resolution LiDAR combined with limited coring could settle the question.

- Landscape story – Integration of cave midden sequences, field-system mapping and coastal change modelling would place the fort in its dynamic shoreline setting.

Dunagoil’s story mirrors the growth of Scottish hill-fort studies itself: from sketch-map curiosity, through artefact-rich trenching and geological detective-work, to today’s laser-scans and experimental furnaces. Each wave of investigation has re-framed the questions, ensuring the charred rampart on its basalt crag continues to fire both imagination and cutting-edge research.