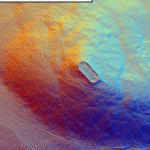

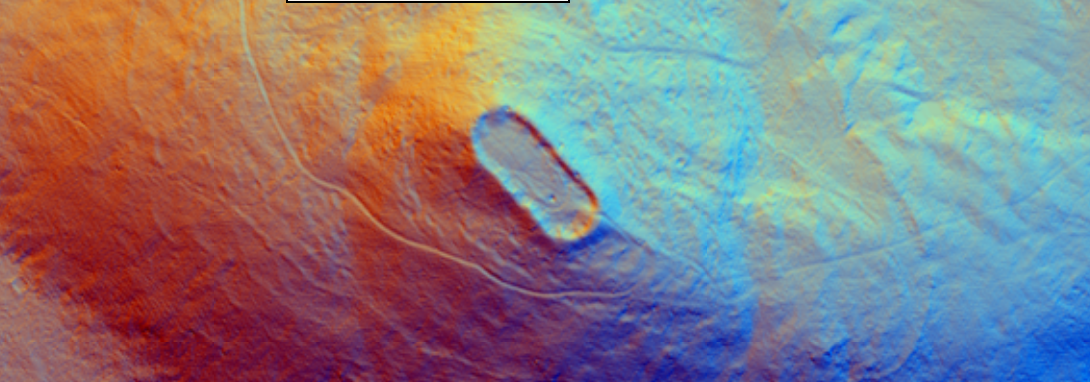

Tap O Noth LiDAR 1m - Thanks to the National Library of Scotland

Tap O Noth Hillfort

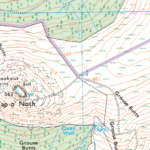

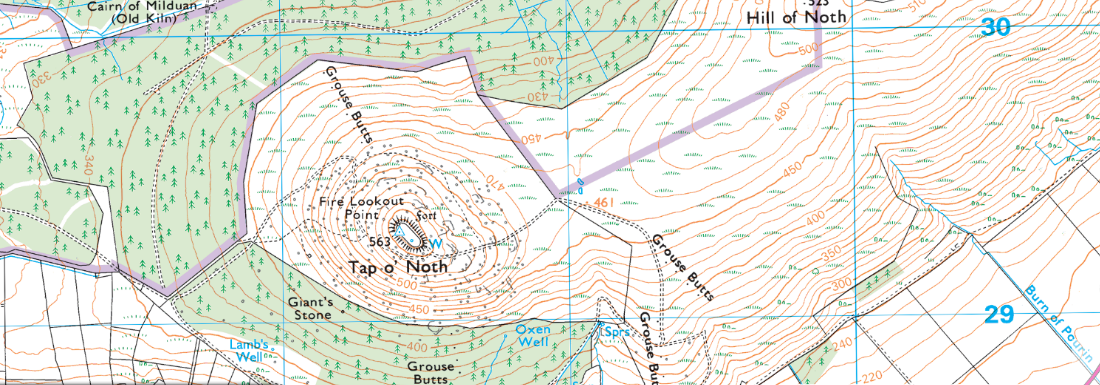

Grid ref: NJ 484 293 Ordnance Survey Landranger series sheet no. 37

20 miles W of Inverurie. The approach to this, the second-highest fort in Scotland, involves a somewhat arduous walk from Brae of Scurdargue, approximately 1 ½ miles NW of Rhynie on the A941 to Dufftown.

Tap o' Noth - geograph.org.uk

Site Description

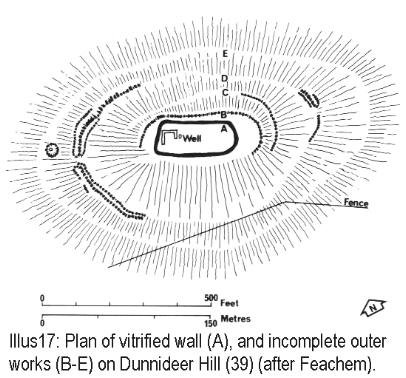

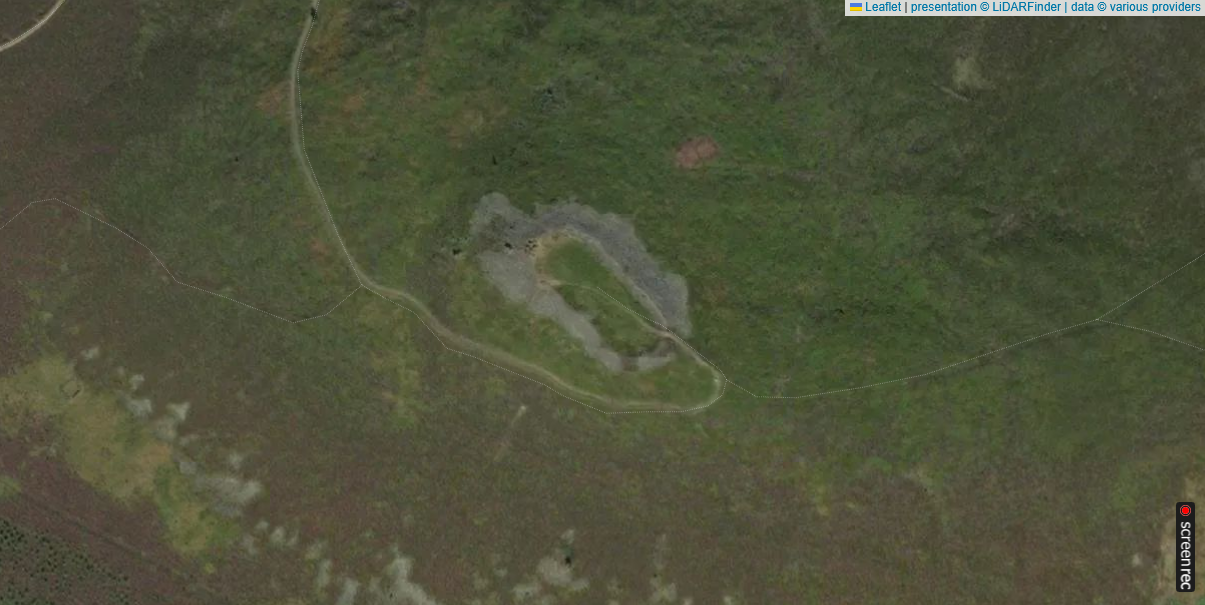

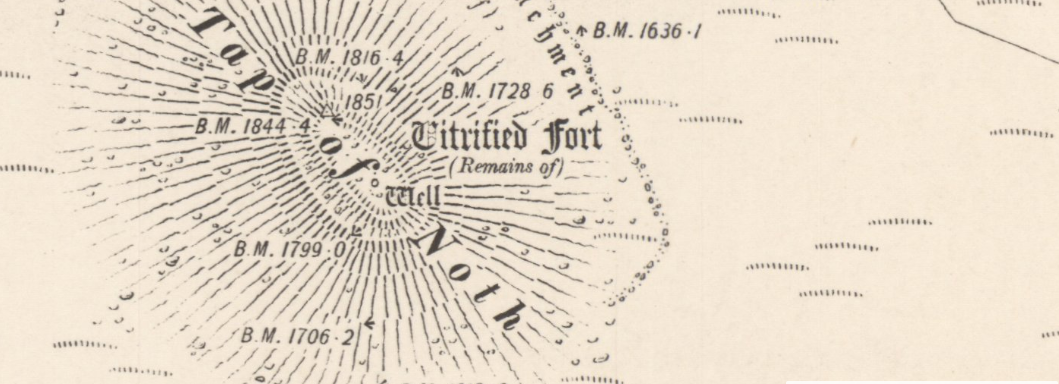

The site crowns the conspicuous 562 m high SW summit of the Hill of Noth. The major feature is the substantial remnant of the vitrified wall, defining an oblong approximately 100 m by 30 m in size. An internal depression, in which water may sometimes be seen, probably served as a cistern for the initial inhabitants. Although it is difficult to imagine such a high site being occupied on a permanent basis, there are slight traces of platforms, perhaps for circular wooden houses, on the S side beyond the collapsed rubble from the vitrified enclosure. Much further out, on the N and E, there is a much less impressive defence, formed by boulders strung out along the flanks of the hill.

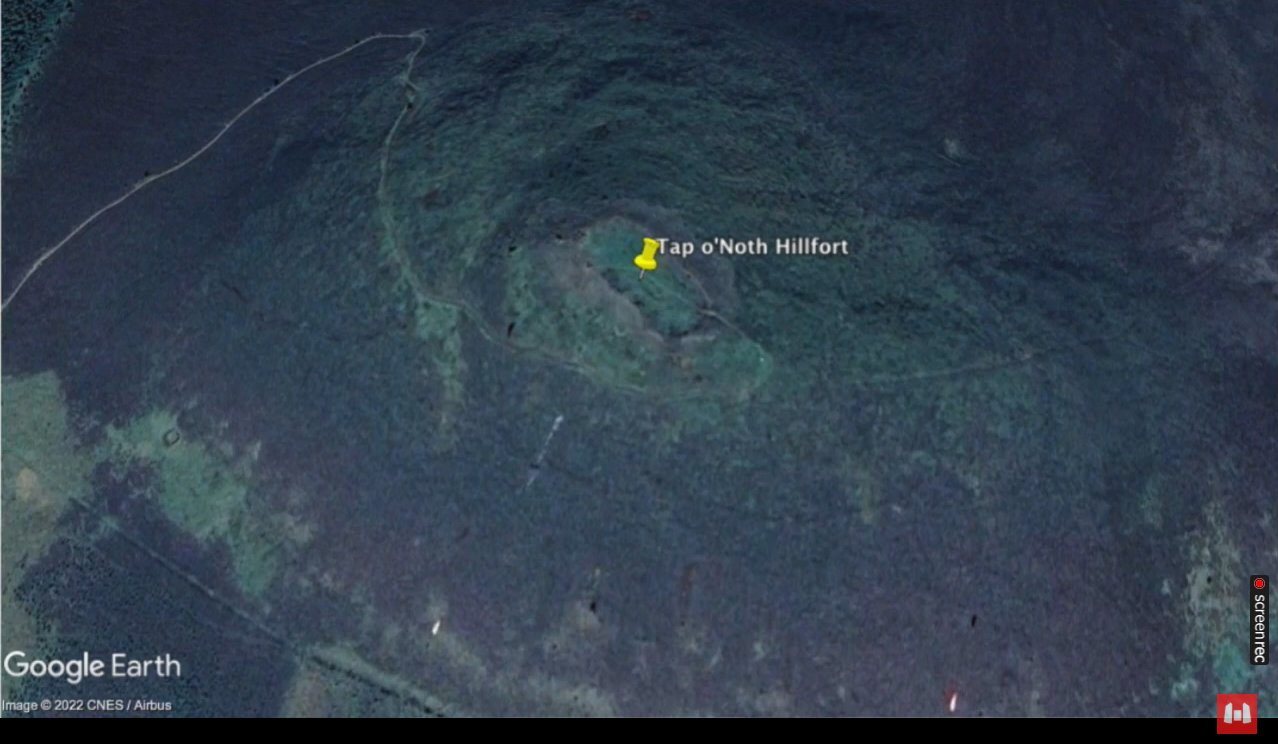

Tap O Noth - Satellite - Google Earth |

Tap O Noth - Satellite - Thanks to LiDAR Finder |

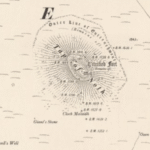

Tap O Noth OS 25000 Leisure Map - Thanks to the National Library of Scotland |

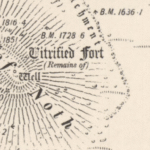

Tap O Noth OS Series 1 map - Thanks to the National Library of Scotland |

Best example of vitrification

This is one of the best examples of a vitrified fort, it is near the village of Rhynie in northeastern Scotland. This massive fort from prehistory is on the summit of a mountain of the same name which, being 1,859 feet (560 metres) high, commands an impressive view of the Aberdeenshire countryside. At first glance it seems that the walls are made of a rubble of stones, but on closer look it is apparent that they are made not of dry stones but of melted rocks! What were once individual stones are now black and cindery masses, fused together by heat that must have been so intense that molten rivers of rock once ran down the walls.

[arve url="https://youtu.be/vQTC4EOq5gw" arve_link="false" autoplay="false" /]

Experimental attempts to replicate the vitrification seen at Tap o’ Noth

The rampart of Tap o’ Noth hill-fort is one of the best-preserved examples of a stone wall whose core has melted and fused into green-black glass. Because the temperatures required (> 1 000 °C) far exceed what an uncontrolled brush-fire can achieve, archaeologists have tried—twice and at full scale—to discover how such heat might have been generated and whether the melting was accidental, structural or deliberate.| Date & lead investigator | Where the replica wall was built | Construction details | Firing regime & peak temperature | Result | Main lessons |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1937 – V. Gordon Childe & W. Thorneycroft | Plean Colliery, Stirlingshire | 3.7 m long, 1.8 m wide, 1.8 m high “murus gallicus”: fire-clay bricks as faces, 30 cm timber lacing, basaltic rubble core. (the urban prehistorian) | 4 t of kindling & logs piled against both faces; fuel replenished for 20 h in sleet. | Wall collapsed inward after 5 h; core stones reached c. 900 °C; 3 kg of bubbly glass recovered. | Timber-laced stone can indeed vitrify, but only where flame and oxygen reach the rubble; a single firing would not strengthen a whole hill-fort but could melt patches. |

| 1980 – Ian Ralston (Yorkshire TV / Aberdeen Univ.) | East Tullos landfill, Aberdeen | 8 m long rampart based on Tap o’ Noth section: outer skin of granite blocks; gabbro rubble core; horizontal oak beams (≈ 30 % timber by volume). (the urban prehistorian) | Continuous pyres plus paraffin & animal fat; wind-shielding tarps; fire stoked for 28 h. Core probe after 15 h read 1 050 °C. | Partial vitrification in beam sockets and mid-core; 3 kg of fused granite-gabbro glass. Wall bulldozed for safety after 28 h while still hot. | Confirmed Childe’s results; showed that > 1 000 °C can be reached in a timber-rich rampart without industrial bellows; but vitrification remains patchy and weakens the structure. |

Key technical findings

- Fuel-to-stone ratio – Both experiments needed c. 1 part dry timber to 2–3 parts stone by volume. That equates to many thousands of mature trees for a full hill-fort wall: mass felling and organised labour are implied.

- Airflow control – Heat concentrated where through-drafts fed the core (beam sockets, gaps between facing stones). Stagnant pockets never melted.

- Glass chemistry – Melted granite and gabbro at 1 050 °C produced the same green-black glass and vesicles seen in Tap o’ Noth samples, vindicating the experimental design.

Behavioural implications for Tap o’ Noth

-

Deliberate conflagration is feasible: a well-planned firing could vitrify selected stretches in one episode, whether as an act of destruction or as a dramatic closure rite.

- Structural strengthening unlikely: both replica walls became unstable once timber burned out; vitrification weakens rather than “welds” a rampart.

-

Labour & resource cost: harvesting and hauling the timber needed for a 100 m-long, 3 m-thick rampart would require a supra-household workforce—fitting a scenario of elite display or punitive destruction, not accidental fire.

- Who lit the fire? —No siege debris or arrowheads were found in Tap o’ Noth’s vitrified tumble; ritualised self-burning remains as plausible as enemy attack.

- Why re-occupy a melted wall seven centuries later? —Pictish re-occupation (7th c. AD) suggests the ruined, glass-fused rampart still carried prestige or ancestral authority despite its weakened fabric.

- Regional pattern: comparable vitrification and radiocarbon brackets at Craig Phadrig, Dunnideer and Dun Deardail hint at a shared cultural practice of “fire-finishing” forts in north-east and Highland Scotland.

Take-away: the Tap o’ Noth experiments demonstrated that Iron-Age builders could intentionally melt a timber-laced wall using only locally available fuel and simple draught control. They did not prove whether the goal was tactical, structural or symbolic—but they push the balance of probability toward a planned, labour-intensive fire that turned a granite rampart into a smoking, glassy monument of power.