Contents

- 1 Wincobank Fort

- 2 Description

- 3 Site visit notes

- 4 Research Notes

- 5 Wincobank Hill-fort, Sheffield, South Yorkshire - Current State of Play

- 6 Research gaps

- 7 Significance

- 8 “Roman Rig” and Wincobank Hill-fort – what scholars think in 2025

- 9 What would settle the debate?

- 10 Review of main features and Archaeological Research

- 11 Site Gallery

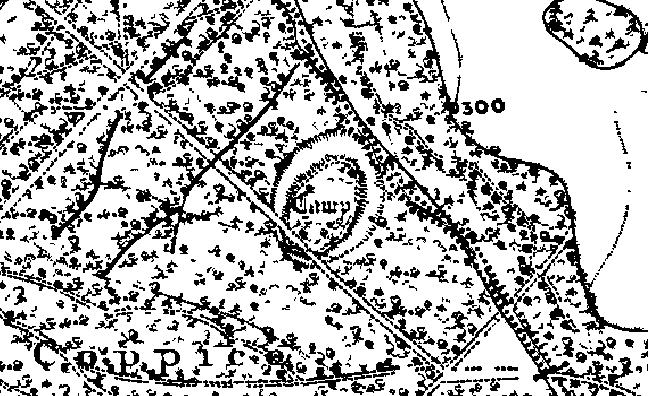

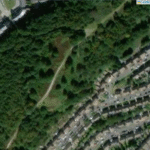

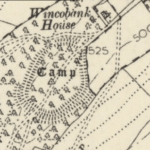

1903 OS map of Wincobank

Wincobank Fort

Location

Wincobank (W.R.), Hillfort (SK/378910) 2.5 miles NE of centre of Sheffield. Finds in Sheffield Museum.

Description

"This is an oval fort with an internal area of 2.5 acres. A bank, ditch and counterscarp bank are continuous around it except on the N side where the ditch and counterscarp have been destroyed. The banks now nowhere exceed 3 ft. in ht. There is an entrance on the NE side, where one end of the main bank is thickened and the other end runs out across it for 30 ft., forming a type of our turned entrance.

Excavation in 1899 showed that the ditch had an original depth of 5-6 ft. The main bank has a rubble core with stone facings. It had contained much timber work holding it together; at some period this had been burnt, accidentally or otherwise, until much of the rampart had been fused into a solid mass by heat. Not dated." - N Thomas, Guide to Prehistoric England.

|

Part of the southern Rampart, and the view to the south from Wincobank |

"The oval 2.5 acre fort at Wincobank, north of Sheffield, almost certainly provides an example of timber-laced rampart construction. Excavations in 1899 (Howarth, 1899) indicated that the internal rampart, surviving to a height of about 3 feet, was 18 feet wide, and had well-built stone revetments. The core was of sandstone rubble, badly burnt and in parts fused, with variable quantities of charcoal and burnt timber. There was an outer earthen rampart with a little burnt wood and burnt stones, and a ditch between the two ramparts. No material remains were found." Later Prehistory from the Trent to the Tyne. Challis and Harding 1975.

Wincobank's vitrified inner rampart.

Site visit notes

I was told about Wincobank by my father-in-law, who said it was vitrified. When I visited, the first bit of rampart I looked at had indeed been fired. I've made lots of fires in my time and the top layer of rock reminded me of rock which had been in an intense fire for several days - we used to have the biggest bonfire around, and I was chief firelighter! I'd call this type of rock example A, I took a chunk of it. As I walked round the inner rampart (this fort looks like it has two ramparts) I could see that this seemed to have been subject to the same temperatures along the entire length of the rampart covering the entire circumference of some 430m and formed a layer which was 3-4 ft wide.

The burnt effect was graduated, with those rocks on the outside of this layer apparently reaching a cooler heat than those in the middle of this layer. Possibly showing that the rocks which were originally on the top of the rampart reached a higher temperature.

As I walked along the rampart I could see many areas where the rock had almost melted and had certainly fused with other rock, I also got a sample of this kind of rock (Example B).

Looking at the samples, example B seems to be several pieces of rock which have bonded together, they all show surface bubbling with bubble diameters of between 1 and 5 mm. Rather than being reddish like example A, example B is much blacker and very black in places

1857 map of Wincobank, shown on the bottom left. Of interest is its relationship to Roman Rig, identified on the upper right.

Research Notes

"This is an oval fort with an internal area of 2.5 acres. A bank, ditch and counterscarp bank are continuous around it except on the N side where ditch and counterscarp have been destroyed. The banks now nowhere exceed 3 ft. in ht. There is an entrance on the NE side, where one end of the bank is thickened and the other runs out across it for 30 ft., forming a type of out-turned entrance.

Excavation in 1899 showed that the ditch had an original depth of 5-6 ft. The main bank has a rubble core with stone facings. It had contained much timber work holding it together; at some period this had been burnt, accidentally or otherwise, until much of the rampart had been fused into a solid mass by the heat. Not dated." Guide to Prehistoric England, Nicholas Thomas, 1960.

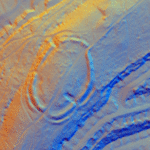

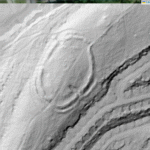

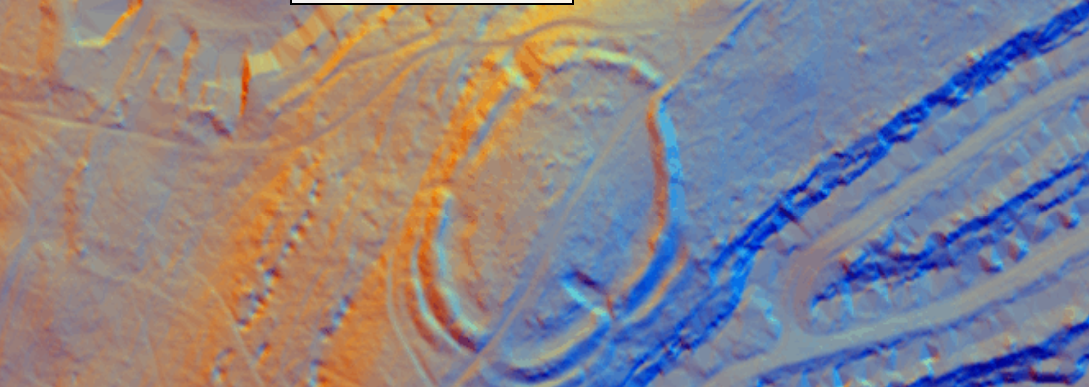

Wincobank Fort – LiDAR – National Library of Scotland 2

Wincobank Hill-fort, Sheffield, South Yorkshire - Current State of Play

| Topic | Current state of knowledge |

|---|---|

| Position & setting | The oval Earthwork crowns an isolated sandstone knoll (203 m OD) on the N side of the Don valley, 4 km NE of Sheffield city-centre. From its crest, the fort overlooks the Don/Sheaf confluence and the Roman-age route east to Mexborough. (Wikipedia) |

| Rampart/ditch system | Encloses c. 1 ha (≈ 2 acres). A single rock-cut ditch, 1.5–2 m deep, surrounds the interior except where the natural Scarp is precipitous. Material from the ditch forms a counterscarp bank, revetted by a 5-6 m-wide stone‐faced wall whose core retains large patches of vitrified Gritstone and charcoal. A slight inturned entrance lies on the SE arc. (Wikipedia) |

| Vitrification evidence | First noted by E. Howarth’s 1899 trenches: the inner stonework had collapsed into the ditch as green-black “slag-like” masses mixed with charred oak. Hand specimen petrography (Beswick 1984) and SEM on 1979 samples show quartz–feldspar fusion at >950 °C. The burning is patchy, implying deliberate firing of a timber-laced revetment rather than accidental brush-fire. (heritagegateway.org.uk) |

| Dating | Charcoal from Beswick’s drainage-ditch section produced a radiocarbon range of 530–360 BC (uncal) – an early or middle Iron-Age construction horizon. No later occupation floors were identified, though re-cutting of the entrance suggests intermittent use. (Wincobank Desktop Assessment) |

| Artefacts | Finds extremely scant: a Shale ring fragment, three pieces of unworked jet, a coarse hand-made potsherd and a few struck flints; a sherd of Roman greyware from earlier antiquarian digging is thought residual. Absence of diagnostic Late Iron-Age pottery echoes other South-Pennine forts. (heritagegateway.org.uk) |

| Later overprint | WWII anti-aircraft gun-platform and searchlight base occupy the SW corner; a Victorian water-main cuts the north bank. None of these features affected the vitrified wall core. (Wikipedia) |

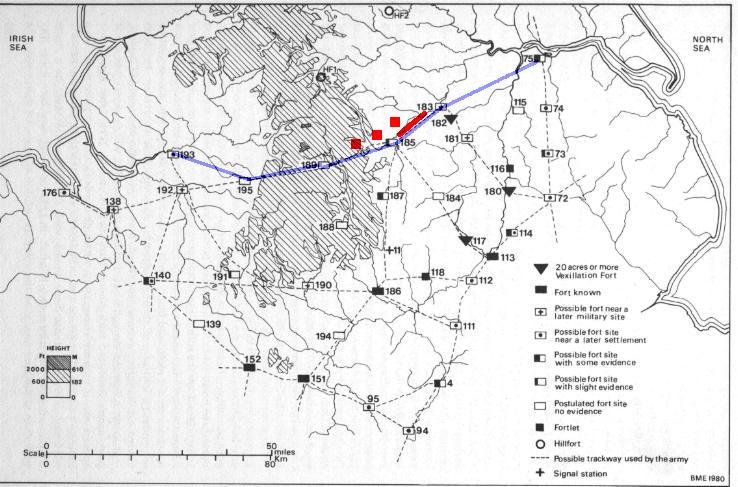

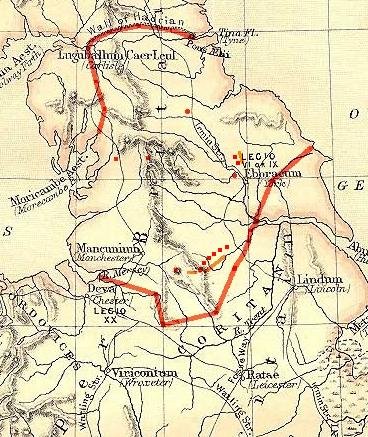

| Interpretation & wider context | Archaeologists now favour a Brigantian attribution and note the fort’s line-of-sight to Carl Wark and Scholes Coppice; together with the bank-and-ditch known as Roman Rig they may form a 1st-century AD defensive cordon against Roman advance. Whether the rampart was burnt during intertribal conflict, as a ritual “closure”, or in response to Rome remains unresolved. (Wikipedia) |

| Management | Scheduled Monument (List No. 1004794). Friends of Wincobank Hill manage scrub clearance and visitor access; small watching briefs (ARS 2016) have ensured recent works do not disturb vitrified zones. (Archaeology Data Service) |

Wincobank Fort – LiDAR – LiDAR Finder 2

Research gaps

- No high-resolution geophysics: magnetometry and resistivity could locate round-house gullies or metal-working floors hidden beneath collapse.

- No modern material science campaign: thin-section petrography and lead-isotope assays would confirm firing temperature and fuel source, allowing comparison with better-studied Scottish vitrified forts (Tap o’ Noth, Craig Phàdraig).

- Environmental coring on the adjacent Southey Wood peat would test for synchronous woodland clearance / fire spike c. 5th century BC.

Significance

Wincobank is the best-preserved vitrified hill-fort in lowland England and a keystone for understanding South-Pennine Iron-Age power. Its fused rampart captures the drama of timber-laced wall construction, high-temperature conflagration and the unsettled politics on the eve of Rome—yet, remarkably, the fort remains under-researched. A small multidisciplinary programme could turn anecdotal vitrification into hard narrative and place Wincobank securely in the wider story of Brigantia.

“Roman Rig” and Wincobank Hill-fort – what scholars think in 2025

| Question | Evidence | Current consensus / open options |

|---|---|---|

| What is Roman Rig? | A sinuous bank-and-ditch up to 8 m wide, 1.2 m high, traceable in discontinuous lengths for c. 4 km from the Don valley at Brightside, past Wincobank, to the Rivelin watershed. First mapped by Hunter (1821); L-IDAR (Environment Agency 2020) confirms at least five breaks caused by quarrying, railway cuttings and housing. | Not a Roman road agger; it is a linear earthwork whose line may link several Iron-Age/Pictish knolls (Wincobank, Scholes Coppice) but is probably not of one build. |

| Has it been dated? |

|

Mixed results: Iron-Age charcoal is likely residual from slope clearance, while medieval pottery shows re-cut or erosion in the Middle Ages. No Roman artefacts confirmed. |

| Alignment with Wincobank | The bank rises to meet the fort’s east ditch, then stops abruptly; no physical junction or construction bond observed. A 2009 resistivity survey showed the Rig cuts across the tail of the fort’s outer counterscarp, not vice versa. | The linear work post-dates Wincobank’s main rampart. If defensive, it re-uses the hill-fort as an anchor, not part of the original fort circuit. |

| Strategic rationale | The line could screen the Don valley approach to the Aire Gap; alternatively, it may demarcate intertribal pasture or woodland rights. Its slight profile would slow stock or foot-traffic, not halt legionaries. | Most researchers now call it a territorial boundary dyke begun in the later Iron Age and maintained or re-cut in the early medieval period. |

| Any Roman connection at all? | No Roman finds or construction methods (agger makeup, metalling) recorded; the name “Roman Rig” appears first on Jefferys’ 1775 county map, reflecting antiquarian habit of labelling big Earthworks “Roman”. | The label is antiquarian, not archaeological: Roman only in name. |

Working model (2025)

- Wincobank hill-fort built and partly vitrified c. 5th–4th century BC.

- Linear dyke(s) laid out sometime after the fort was already ruinous; hazel charcoal in the ditch may be clearance debris rather than construction residue.

- The dyke’s intermittent maintenance into the medieval period explains the small later pottery scatter.

Thus, the “Rig” is not a Roman defensive outwork, nor was the fort built as a bastion in a single continuous frontier line. More likely, later communities saw the prominent fort and aligned their own land-boundary bank to take advantage of its commanding position—recycling Iron-Age prestige into early-medieval territorial geography.

What would settle the debate?

- Wide-area LiDAR & soil-magnetism to confirm whether all segments share one ditch plan.

- Paired OSL & AMS dating on primary ditch fills from several segments to test for a single construction horizon.

- Palaeoenvironmental transects down-slope: a synchronous spike in charcoal/pollen clearance might reveal a large coordinated building phase.

Until then, “Roman Rig” remains best described as a multiphase boundary dyke that later peoples draped across the flank of an older, vitrified hill-fort, not as a purpose-built component of Wincobank’s Iron-Age defences and certainly not as a Roman work.

Review of main features and Archaeological Research

Monument Layout & Construction

-

Form: A slight univallate (single-bank) enclosure roughly 130 m by 80 m (internal area ~1 ha).

-

Defences: Originally surrounded by a 1.5–2 m-deep ditch, with the Upcast earth forming a turf-faced rampart up to 3 m high. A counterscarp bank of rubble lay beyond the ditch en.wikipedia.org.

-

Revetement & Vitrification: Stone facings held in place with timber elements, some of which were vitrified (charred by intense heat), suggesting at least one episode of deliberate burning—perhaps during inter-tribal conflict around the 4th–3rd century BC en.wikipeia.org.

Entrances & Internal Features

Early scholars misidentified breaks on the NE and SW sides as gates; detailed survey shows the true entrance on the SE side, where the bank turns inward and where a small mound—possibly a watch-tower base—still survives historicengland.org.uk.

"Gold Medallion of Constantius Chlorus" by AncientDigitalMaps is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0 |

"Medallion of Constantius Chlorus" by AncientDigitalMaps is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0 |

Archaeological Investigations

-

Howarth (1905) cut a drainage trench through the NE rampart, recovering 2nd-century Roman sherds and a Constantius Chlorus coin, evidence of later reuse or rubbish dumping rather than primary occupation btckstorage.blob.core.windows.net.

-

Preston (1950) and subsequent field surveys confirmed the bank-and-ditch profile and found no Roman road surfaces—underscoring its non-Roman origin btckstorage.blob.corewindows.net.

-

Historic England Scheduling (2024) notes Mesolithic–Bronze Age flint scatters around the hill, but no definitive post-Iron Age re-fortification. During WWII an anti-aircraft gun platform and searchlight emplacement were installed in the SW rampart gap historicengland.org.uk.