Craig Phadrid Hillfort

Region : Scottish Highlands District : Inverness Town or village : Inverness Grid Reference : NH 640 452 Period : 500 BC-AD 600

Craig Phadraig is a hilltop fort within a Forestry Commission plantation, 2.5km west of Inverness. It occupies a position with excellent views over the Beauly Firth. The rectangular area enclosed within the ramparts measures 75m x 23m. Radiocarbon dating indicates that the fort was built in 5th or 4th century BC. The site comprises two steep ramparts, which are mainly grass grown. These were constructed of timber laced stonework and then burnt, producing extensive vitrification. A vitrified part of the wall can be seen near a pine tree at the northern end.

The ramparts are grass covered, the inner stand 4m high externally and 1m internally, the ruined ramparts spread some 10m in width. No entrances to the inner rampart have been found. The interior of the fort has an area of 0.2 hectares.

The outer rampart is much slighter, a mound in the eastern corner may be natural.

Excavation in 1971 has produced evidence of re-occupation in the time of the Picts, 6th century AD.

Research Notes

"The construction of the circling rampart at Craig Phadrig has been examined in detail, and the basic principles there established probably apply to all forts within the Inverness area. The total thickness of the wall at Craig Phadrig was just under 21 feet (6 m.) and, on the basis of the quantity of the collapsed debris still remaining, must have originally stood at least 26 feet (8 m.) high. The rampart consists of two revetments enclosing a rubble core. All stone was obtained locally if available, by surface collection, although for some forts (including Craig Phadrig?) quarrying must have been essential, particularly for suitable blocks for the revetment

The rampart was founded on the natural turf, no previous preparation having been undertaken except the marking out of the line of the wall. In some cases it is suggested that the rampart was founded on a raft of logs, but no examples of this type appear in this area.

The revetting walls were carefully constructed, each occupying about one-third of the total width of the wall at the base, and gradually thinning as the structure reached its full height. The lowest yard (m.) is invariably constructed of very large blocks to provide an adequate foundation, while above this smaller blocks were used, and frequently timber lacing was introduced into the design.

Clear evidence of horizontal timber beams running from the inner revetment into the core was found at Craig Phadrig, and circumstantial evidence supports a network of horizontal, transverse and vertical limbers tying the inner revetment thoroughly to the core.

Although timber beams appear in the outer face of some continental forts, they never did so at Craig Phadrig. Besides its value in tying revetment to core, limber lacing has the advantage of preventing a large section of the core "running" should the outer revetment be breached by attackers. If that happened, a natural causeway would be provided for the invaders. Furthermore, timber lacing has the property of spreading the weight-load in a massive structure. Brochs built entirely of dry stone, without any timber lacing, frequently show intensive shattering and cracking of stones in the lower courses due to the pressure from above.

Small finds and continental parallels were the original dating criteria for fixing these forts firmly within the Celtic Iron Age, and the use of radio-carbon dates on the Scottish forts in the last decade has confirmed the date for Craig Phadrig, to be 350 B.C.; Craig-marloch Wood. The evidence from several sites, including Craig Phadrig. Suggests that the primary fort survived for a relatively short time, and was refurbished later.

"A preliminary examination of the bones from Craig Phadrig shows a high proportion of red deer, and also possibly reindeer. The European wild boar is also recorded. Of the pastoral animals, cattle were by far the most important." The Hill Forts of the Inverness Area, ALAN SMALL

Craig Phadrig hill-fort, Inverness

| Topic | Current understanding |

|---|---|

| Topography & plan | A sub-rectangular summit enclosure (c. 75 m × 25 m) crowns a 172 m-high knoll overlooking the Beauly Firth. Two stone ramparts – an inner wall up to 8 m thick and an outer belt 15-20 m below – ring the crest; both display extensive vitrification (quartz-rich stones fused to glass). No original entrance is visible. (Canmore) |

| Excavation history | ● 1920s probing by H. Dryden and W. J. Ross;● 1953-57 full trenching by J. R. C. Hamilton;● 1971-72 sampling by A. Small;● 1993 RCAHMS survey; recent Photogrammetry for Forestry & Land Scotland. Radiocarbon on rampart charcoal gives construction/first burning in the mid-1st millennium BC (409–176 cal BC). Finds of imported E-Mediterranean amphora sherds, bronze pins and crucibles in overlying floors show re-occupation in the 7th century AD, probably as a Pictish royal seat (Bridei mac Maelchon). (Wikipedia, Highland Pictish Trail) |

| Nature of the vitrification | thin-section and SEM work (Dolan 2020) confirms temperatures > 1000 °C: quartz melted, feldspar partially fused, vesicles show timber-fuel dehydration. Fusion is patchiest where timber revetments once abutted stone, matching experiments at Tap o’ Noth and Loup of Fintry. (Stir University DSpace) |

| Why was the rampart burned? | Deliberate strengthening is unlikely (fusion is irregular and weakens the stone). Excavators now favour destructive conflagration – either: 1) an enemy attack/abandonment at the close of the Iron-Age phase; or 2) a ritual “closure” at the point of Pictish re-fortification, symbolically purging earlier defences. No weaponry or siege debris was found in Hamilton’s burnt tumble – leaving intent unresolved. (NOSAS Archaeology Blog) |

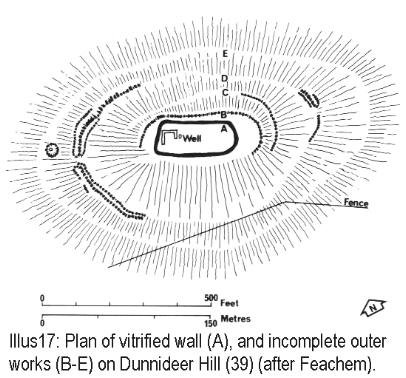

| Regional context | Craig Phadrig belongs to a cluster of Moray Firth vitrified forts (Finavon, Dunnideer, Tap o’ Noth) – all timber-laced, all apparently burned between 400–100 BC. Later Pictish re-use of such vitrified sites is noted at Burghead and Dun Deardail, supporting the idea that early-medieval elites re-occupied “ancestral” hill-tops for political theatre. (Arch Highland, Antiquaries of Scotland Journals) |

Key points on vitrification

- Fuel & method: experimental firings show a timber framework packed tightly against dry stone can reach vitrifying heat within 24 h; Craig Phadrig’s vesiculated glass matches this model.

- Scale: only the inner wall is consistently fused; outer circuits show patchier burning, suggesting a single, short-lived conflagration of a timber-laced revetment rather than repeated attempts.

- Chronology split: vitrified collapse is Iron-Age, but occupation debris (hearths, iron slag, imported pottery) above the tumble is Pictish. The fort was therefore repaired or re-inhabited centuries after the fire, not destroyed in the Pictish period.

Unresolved questions

- Trigger event – was the burn offensive (siege) or internal (ritual abandonment)? Lack of weapon finds leans to internal.

- Extent of Pictish rebuilding – the visible rampart is much reduced; whether Picts rebuilt in timber over fused stone awaits geophysical mapping.

- Political role – if Craig Phadrig was Bridei’s seat, is vitrification a memory device enhancing dynastic legitimacy by displaying a “fire-forged” ancestral wall?

Future work possibilities

- High-resolution magnetometry could trace hidden timber-slot lines and confirm entrance positions.

- Dendrochronology on surviving charcoal lenses may refine the Iron-Age firing date.

- Comparative glass chemistry across the Moray Firth forts may reveal whether a single conflagration tradition swept the region, or each fort burned in isolation.