Mickley Riverworks

← Wensleydale

Kilgram Bridge Ford

Kilgram bridge itself is of known ancient construction, and is believed to date from the early 12th century - probably Read more

Marrick Priory

Marrick Priory, a historic gem nestled in the Yorkshire Dales, has a rich history that dates back to the 12th Read more

Carperby in Wensleydale

Carperby, nestled in the heart of Wensleydale, North Yorkshire, is a village steeped in history and archaeological significance.

Tamworth Castle

Tamworth Castle, has known origins that trace back to Anglo-Saxon times when it served as a residence for the Mercian Read more

Site Details:

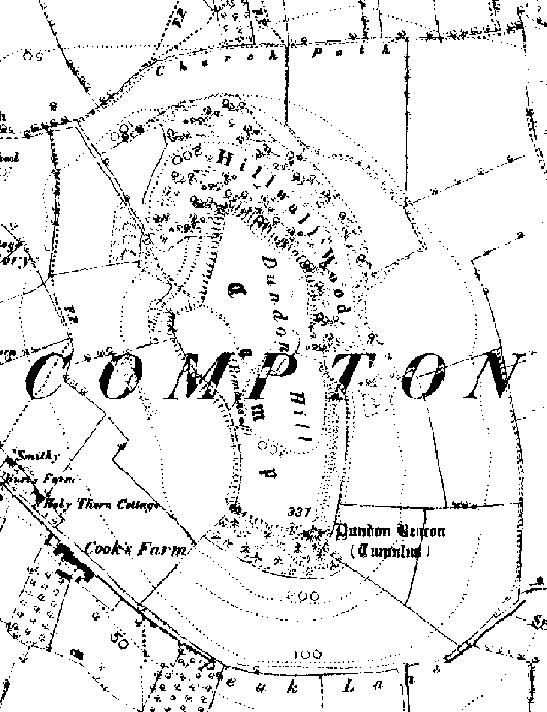

Mickley Mill, its weir-and-leat system, and the rumour of a Roman ford

| Element | What we can document | Key evidence |

| Industrial complex | Flax (formerly corn) mill built c. 1790–1810 on the south bank of the Ure. A 65 m-long angled weir diverts water into a 620 m leat that hugs the foot of Mickley Barras Wood before re-entering the river at a tail-race just above the mill ruins. 1851 census lists c. 100 mill hands; the mill closed c. 1882 and was dismantled after 1892. | Grewelthorpe local-history article with census abstracts and sale notice ; Geograph photographs of the surviving weir, leat embankment and mill race . |

| Hydraulic engineering | The weir occupies a pre-existing shale riffle only 0.5–0.7 m deep in summer flow—ideal for both a ford and a mill-head. 19th-c. stone pitching is visible on the weir crest and on the leat head-wall; sluice-gate ironwork survives in situ. Modern EA monitoring site “Mickley New Weir” records 1.2–1.5 m head in normal flow. | |

| Any earlier mill? | No mill is shown on Jefferys’ county map (1771) or the 1767 Bolton-estate terrier, suggesting the complex is strictly late-Georgian onwards. | |

| “Roman ford” tradition | Anglers and canoeists still talk of “Roman Ford” on the Swinton fishing beat immediately upstream of Mickley (turn4search0) and the name appears in estate fish-catch returns from the 1920s. The idea is that a paved crossing pre-dated the weir and was later buried beneath it. No Roman finds have been reported to PAS or the Historic Environment Record. | |

| Topographical clues | A shallow gravel bar beneath the present weir gives the only natural fording point for c. 4 km upstream and 6 km downstream—matching Roman practice of choosing pre-existing shallows. A straight, partly causewayed track shown on the tithe plan (1845) and LiDAR leads off the south bank towards Malley Bank, aligning with the Bridle Lane to Aldfield, which, in turn, lines up with the known Roman road from Aldborough/Isurium to Bainbridge/Virosidum. | |

| Comparative precedent | At Kilgram Bridge (10 km upstream) the medieval bridge was built directly over a paved Roman ford that can still be seen at low water (turn4search1). The Mickley-weir locality therefore mirrors a proven Roman practice on the same river. | |

Weighing the Roman-ford hypothesis

| For | Against |

| The natural riffle sits at an obvious route-node between Nidderdale and the Dere Street corridor. | No artefacts, coins, or paving blocks have yet been recovered at Mickley. |

| 19th-c. engineers exploited the same spot for a weir – common where earlier paved fords gave a firm foundation. | Roman road alignments from Aldborough towards the Ure are not continuous on the ground; the main Catterick–Bainbridge route crosses at Kilgram, not Mickley. |

| Persistent folk-name “Roman Ford” in estate and angling lore (at least from 19th c. onwards). | Folk names alone are not proof; similar names occur where late-medieval fords reused Roman-looking cobbles. |

High-level assessment: the Mickley riffle

could have served as a Roman (or later) vehicular ford that was buried under the weir apron after 1790; but there is

no hard archaeological evidence yet. Its strategic setting and the

Kilgram analogue make the idea worth testing.

Research steps that would answer the question decisively

- Under-water and bank-edge survey at low summer flow: look for laid sandstone sets, timber sill-beams, or iron wheel-ruts.

- Twin-auger transects across the leat head and weir toe: if a cobble surface lies below the 18th-c. stone pitching it should survive as a distinct horizon.

- Ground-penetrating radar along the south-bank causeway to map any metalled approach road buried under alluvium.

- Archive trawl: estate road-repair ledgers (Bolton, Swinton) c. 1740–1790 may mention “old ford paving” or payments to lift stones before the new weir was built.

- Surface artefact scan on fallow fields in either bank: Roman hob-nails, pottery or brooch fragments would strengthen the case for a maintained crossing.

Why the site matters whether or not it is Roman

- Industrial archaeology: Mickley’s leat-and-weir ensemble is one of the best-preserved rural flax-mill water systems in the Ure catchment.

- River-ecology barrier: the weir is now a partial fish obstacle; any restoration scheme must respect its heritage status.

- Landscape story-telling: from possible Roman crossing to Georgian industry to 21st-century salmon monitoring, the spot embodies two millennia of Ure-side ingenuity.

So the “Roman ford” remains an informed possibility, not established fact—yet it flags Mickley as a perfect candidate for small-scale geo-archaeological testing that could, quite literally, put another Roman crossing of the Ure on the map.

Site Gallery