Site Details:

For over five hundred years, the miners and smelters of Reeth produced mountains of precious lead. The lead ores from Reeth had high concentrations of Silver, Lead itself became an important ingredient in bronze. Maiden Castle, deep in the Swaledale lead mining territory a unique piece of Iron Age architecture. It is the only known fort with what seems to be a processional entrance.

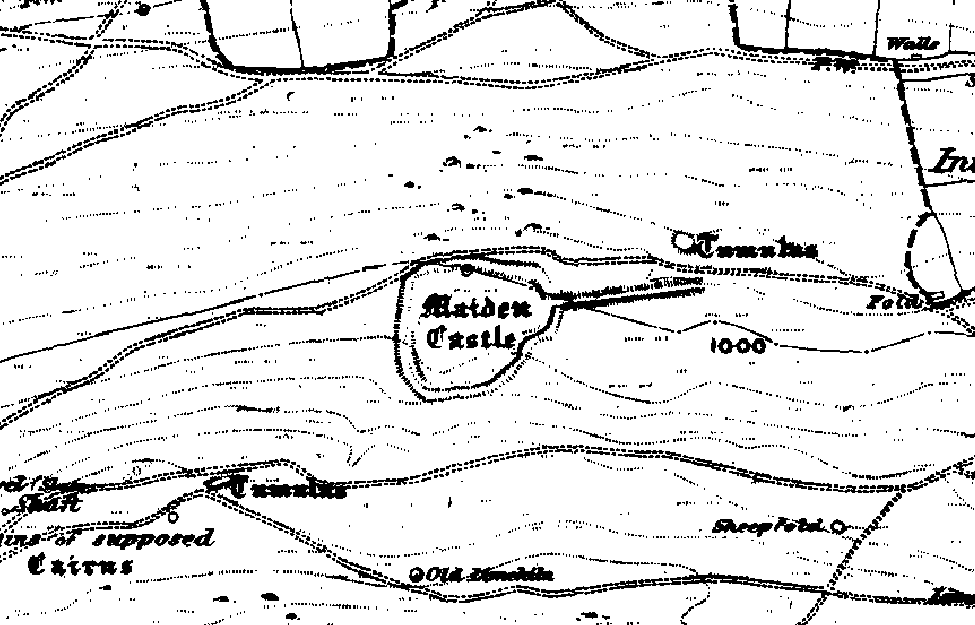

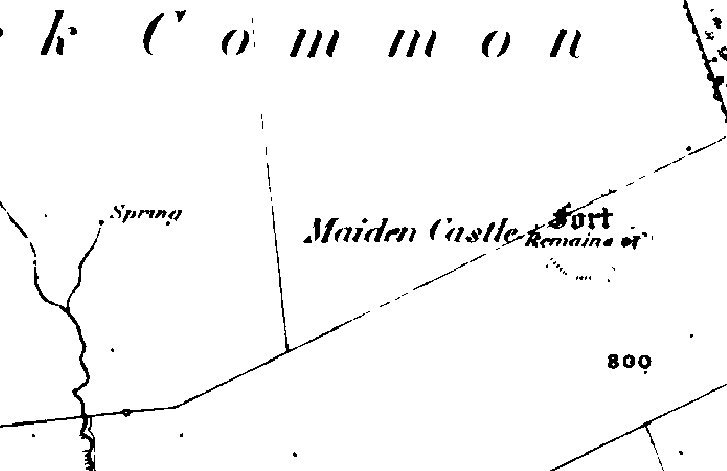

Maiden Castle, Swaledale. The long entrance wall can be seen to the left of the picture.

Maiden Castle

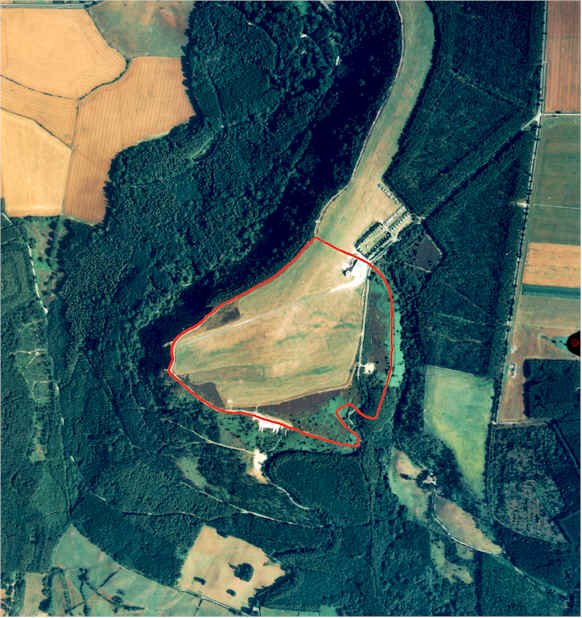

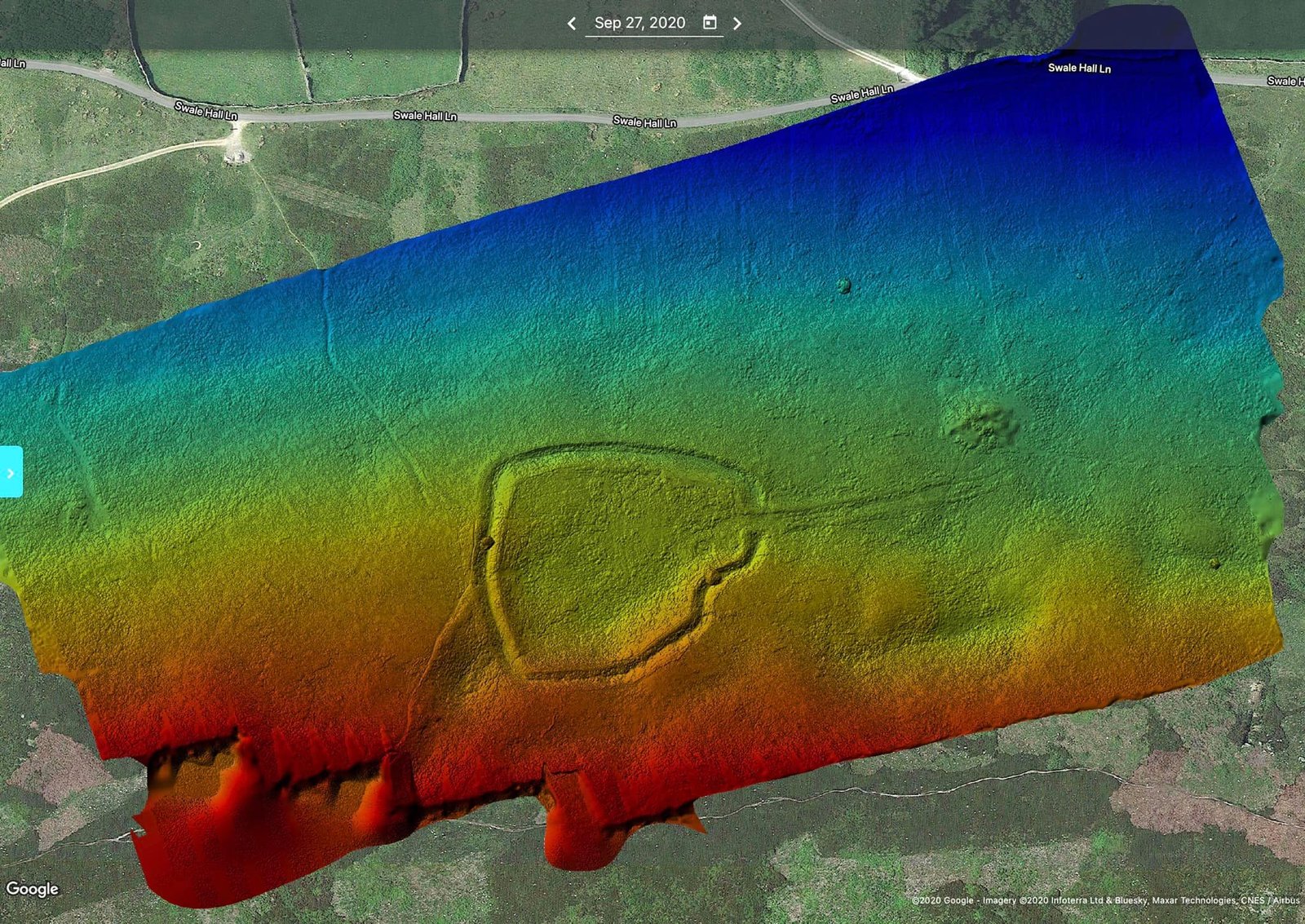

Air photo of Maiden Castle, from Multimap.

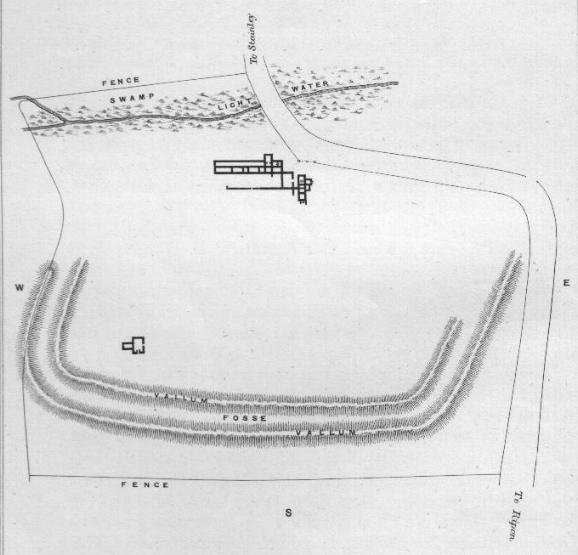

The Entrance Corridor

The only entrance to Maiden Castle, shown on the left, is via a 110m stone corridor.

Introduction

This is one of the most unusual forts in the British Isles, it combines a slightly odd but otherwise ordinary hill fort of the Iron Age period with a unique stone entrance corridor. The corridor was originally some 6-8m wide, lined with an unusual wall, it was completely parallel, very long, and tapered to a very low height.

The wall of the corridor has largely collapsed but in places the original dry stone walling still persists. The wall can be seen to 'taper' as fewer and fewer stones were used in its building the further away it gets from the fort. Originally, the wall must have started at a height of .5m or so and rose to perhaps 4m by the time it reached and joined the fort. The southern wall was not as big but followed the shape of the north wall.

Research Notes

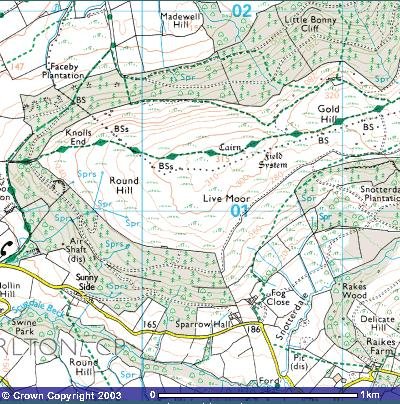

"... Maiden Castle at Grinton in Swaledale, is a curious place with a roughly circular bank and ditch approached from the east by a stone avenue. There are round barrows in the vicinity, and although the ditch lies outside the bank, it seems very probable that Maiden Castle is not a fort but some kind of sacred enclosure or meeting place" Jacquetta Hawkes, A Guide To The Prehistoric And Roman Monuments In England And Wales. Pub. 1978 Abacus

"Among the Pennines and the North Yorkshire Moors, too are linear earthworks comparable to those in the Parisian territory. Certainly, not all are Iron Age, but a strong case can be made for some. The usual suggestion is that these are ranch boundaries. At Maiden Castle, on the southern slope of Swaledale west of Grinton, a ditched enclosure of rather less than an acre with a stone wall has a stone-walled drove road leading to it from the east. This is comparable in its general nature to the 'banjo' enclosures of the south, and we are inclined to accept its Iron Age date." The Brigantes Brian Hartley and Leon Fitts. Pub. Alan Sutton 1988

"Mention should also be made of a type of small enclosure (normally less than 1.5 acres) with long entranceway which in the majority of cases is funnel-shaped: the banjo enclosure (Perry, 1966). The distribution seems to be confined mainly to Hampshire, Dorset, and Wiltshire, where the date on available evidence seems to cover the middle to later Iron Age. Two examples are known in the north of England. One at Risehow, Near Maryport, Cumberland (Blake, 1959, 11-2, fig.2), was dated by finds from an interior building to the later fourth century A.D. The corridor extending from the enclosure led to a drinking place still used by cattle. The other, at Maiden Castle in Swaledale (centred SE 022981), is situated on a hillside terrace. An area 320 by 240 feet is defined by massive earthworks, including a ditch up to 9 feet deep and an internal rampart of rubble with coursed dry stone facing. The shape is angularly oval, with two rounded corners at the broader western end, and an entrance at the eastern, narrower, and defined by well constructed wall termination's 15 feet apart. Extending from the entrance is a walled corridor 390 feet long and 17 feet wide. There is no dating evidence for Maiden Castle; it may be post Roman and related to the nearby Reeth and Fremington Dykes. However, its hill slope situation precludes a military function. Both these northern banjo enclosures probably served as cattle enclosures and defended homesteads" Later Prehistory from the Trent to the Tyne, Challis and Harding, 1975.

Brigantes Nation comment - George Chaplin

It is probable that both the Hartley and Fitz, and Challis and Harding comments come from interpretation of the same source, and both are swayed by the inclusion of it in the categorisation of it as a banjo enclosure. However, neither have benefited from a detailed survey of the fort, judging by the evidence available, this site has not been excavated, so most comment must be accepted as conjecture. Its categorisation as a banjo enclosure (even though it looks more like a banjo than any other) does it a disservice by allowing the possibility that it could have shared similar function. However, this enclosure has it's own unique environment - deep in an area plentiful with lead, copper and Silver, as well as other valuable mineral and ores. Note that all other banjo enclosures have a funnel shaped entrance, this very much does not, and its tapering structure for the entrance will have served as a very poor drove road.

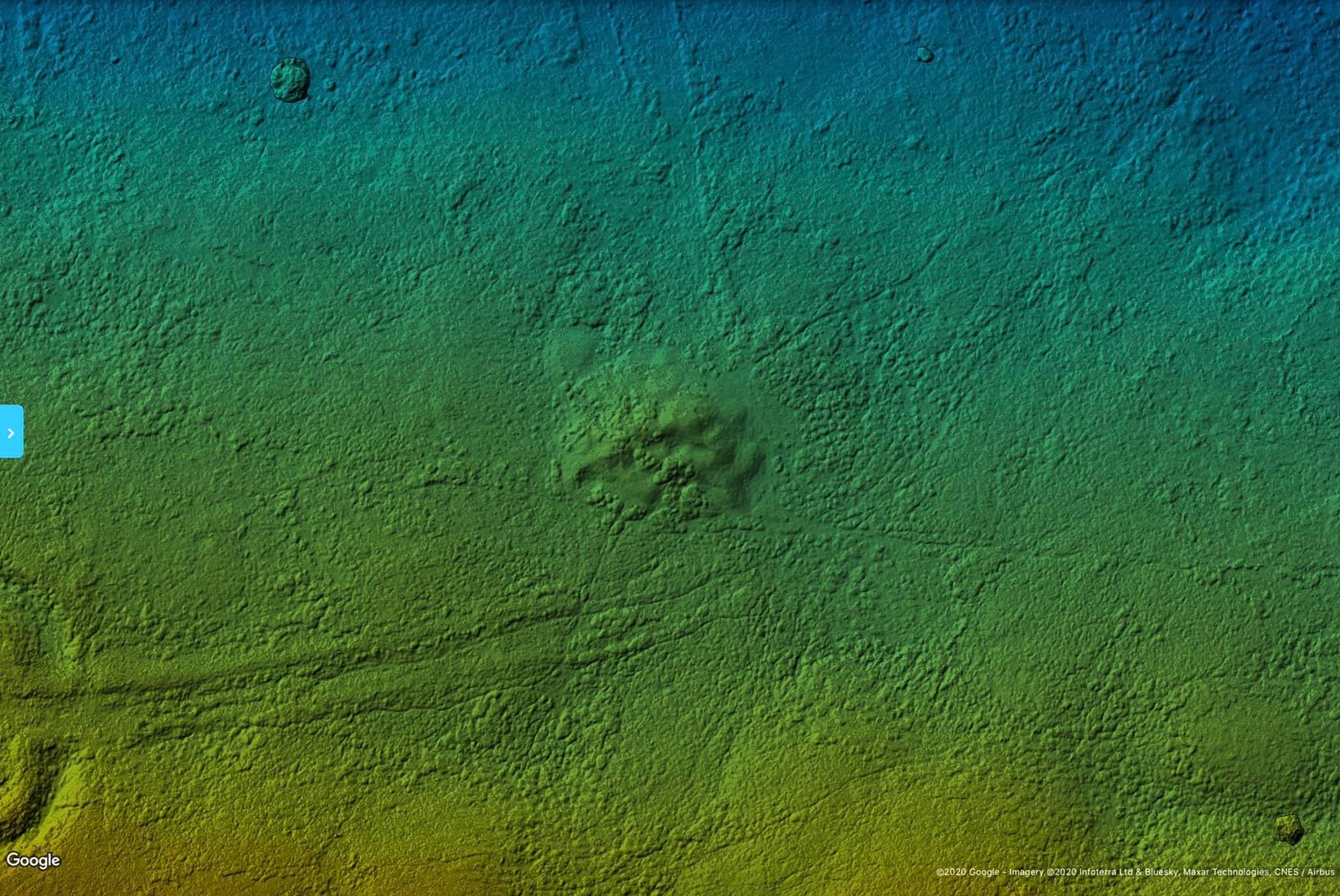

A huge tumulus marks the entrance to and is seen in the distance, this picture shows the straight parallel nature of the entrance, and shows the width of the wall 'spill' at its point closest to the fort.

Challis and Harding take its physical location to indicate a non - hillfort function, since it is overlooked by the hillside, but again this is a sample taken out of context with the contemporary environment. Less than ten miles away a further two hill forts enjoy similarly poor strategic location, both are in mining areas, it appears that building hillforts on the level or a slope was a common practice in Brigantia, and was possibly typical of the region.

Difficult to see but there is some fragmentary original wall shown here, at a site around 20m away from the fort end of the entrance walkway. These rocks are not very large, this is the base of the wall, which tends to indicate it was not likely to be more than 2m high and by the amount of stone that remains, probably lower.

The original wall of the entrance.

If a relationship did exist between the Reeth and Fremington Dykes, then this would indicate a need to defend the area rather than simply a small stockade, making the choice of location for the main settlement to be more of convenience than military stratagem.

Maiden Castle may have come into being around 600 B.C., Perhaps as new settlers moved in to exploit the metal and mineral resources of the area. Over time, as the population expanded and became more structured, people began to settle in the surrounding areas, away from the fort and closer to the mining areas.

Maiden Castle rampart, viewed north from the entrance.

Later, the fort may have ceased to exist as a defensive structure altogether, and perhaps took on a more ritual or ceremonial role for the local people, with the addition of the exaggerated entranceway.

Later still, when the local people were under threat, they may have chosen to raise mighty dykes against their enemies, since they were possibly too numerous and widely spread to retreat to the old fort.

Maiden Castle west rampart, viewed from the south.

The Reeth and Fremington dykes are worthy of mention, in all they show three possible lines of boundary, seemingly protecting from attack from the east. The size of these banks and ditches is so large that they clearly served a more military purpose than as a simple boundary. That there are three lines of them, pretty closely spaced indicates border movement and therefore conflict.

Maiden Castle will probably have ceased to be used by the early part of the Roman occupation of England.

The tumulus by the entrance to Maiden Castle

Site Visit Notes - Fitzcoraldo - TMA

I approached Maiden Castle from Harkerside Moor, the weather was filthy with fog and rain. I was also hassled by screeching peewits who are currently in the middle of their breeding season, the only other sound to be heard was an intermittent cuckoo.

The site is on the north-facing slope of Swaledale and quite difficult to spot.

So what is it? I don't know, but it isn't half impressive and must have taken some building. Firstly, you've got a tumbled down dry stone avenue 4m wide and 110m long. The avenue runs from the east and appears to narrow to about 3m at the entrance to the enclosure. At the beginning of the avenue is a large mound, which may be a spoil heap, but I don't think it is, especially being so close to the entrance. There is a structure built into the avenue, but I think this may be a recent grouse butt. The enclosure itself is a massive wonky pear shape 140m (E-W) X 120m (N-S). It is surrounded by a rubble wall and a deep ditch 4m deep with steep sides and 10m wide. The floor is fairly flat with 1 possibly two stone structures built into the southern side of the entrance.

The site is overlooked by the hillside on the southern edge, so could not be a defensive structure, the enemy could fire down into the enclosure. The site does not dominate the hillside but fits neatly into it and cannot be seen from the road, which is only 200m away. The structure seems too elaborate and too large to be an animal enclosure, why bother building a huge ditch and wall when a gorse hedge would suffice. There are many man-hours in this structure.

To get a good idea of the site, check out the aerial photo on multimap at 1:10000. It has the feel of Mayburgh Henge but hmm… The wall is inside the ditch....... I just don't know If you want to visit, the easiest way is to take the Grinton, Crackpot (really!) road and walk the 200m up the hillside, it's well worth it.

A view of the strip lynchets on the western skirts of Reeth, more evidence of ancient occupation.

Site Visit Notes:

Other Notes:

Maiden Castle in Grinton, a prehistoric site of significant historical interest, has long intrigued archaeologists and historians alike. The latest research suggests that the entrance causeway, which has been a subject of much speculation, may have served a more complex purpose than previously thought.

Excavations have revealed large corner and facing stones forming a 5-meter-wide entrance, indicating a grand approach to the settlement. This entrance, coupled with a length of banking and a short stretch of wall on the internal south side, is believed to be the remains of an enclosure for gateway protection.

Such features suggest that the entrance was not merely functional but also symbolic, possibly denoting power or status. The strategic placement of the causeway, along with the adjacent round barrow, points to a carefully designed landscape that considered both defence and ceremonial procession.

This aligns with broader Iron Age practices of creating imposing fortifications that also served as communal spaces for gatherings and rituals. The ongoing analysis of the site continues to provide insights into the social and political structures of the period, offering a glimpse into the lives of those who built and used these ancient spaces. Maiden Castle's entrance causeway, therefore, is not just an architectural feature but a portal into understanding the complex societal dynamics of prehistoric Britain.

The entrance to the fort is particularly unique, approached by a stone-walled avenue that stretches for 114 meters and is 6 meters wide, creating a grand approach to the site. This corridor-like avenue is not only striking in its construction but also suggests a deeper, possibly ceremonial significance, aligning with the processional nature of other similar prehistoric sites. The layout of Maiden Castle is oval in shape, measuring 108 meters east to west and 88 meters north to south, which allows for a spacious interior that could have supported a sizable community. The strategic placement of the fort offers expansive views of the surrounding dale, which would have been advantageous for surveillance purposes. Additionally, the proximity of round barrows near the site hints at a complex landscape where burial practices and daily life were closely connected. The earthwork on the east side of High Harker Hill is another intriguing aspect of the area, suggesting further activities of significance may have taken place there. The relationship between Maiden Castle and the nearby large round barrow is particularly suggestive, drawing parallels to the arrangements of long barrows and posted avenues found in eastern Yorkshire, which are thought to have ritualistic importance.