Celtic Heads

Celtic Head from Witham, 2nd c B.C. (British Museum) "Celtic" carved heads are found throughout the Read more

Timeline 60BC – 138AD

This timeline is focussed on the British Celtic culture and those cultures which had influence on the British Celts. It Read more

Cartimandua

Yorkshire, and much of northern Britain was also ruled by a queen, the most powerful ruler in Britain in fact. Read more

Caratacus

Caratacus was highly influenced by the Druids, and both he and his brother Togodumnus were among the leading lights of Read more

Cerialis Petillius

Quintus Petillius Cerialis Caesius Rufus was the son-in-law of Vespasian Cerialis and became Governor of Britain in AD.71; his instructions Read more

Julius Caesar

Ask anyone to name a famous Roman character, and the name of Julius Caesar is sure to be the most Read more

Vespasian

Born in the year 9 at Reate, north of Rome, Vespasian was the son of a tax collector, Flavius Sabinus Read more

Augustus

Suetonius wrote of him: He was very handsome and most graceful at all stages of his life, although he cared Read more

Claudius

Tiberius Claudius Nero Germanicus was born Lugunum in 10 BC, the youngest son of Nero Drusus, brother of Tiberius. He Read more

Celtic Gods

Many Celtic deities seem to have been associated with aspects of nature and worshipped in sacred groves. Some appear in Read more

Raimund KARL (a8700035@unet.univie.ac.at)

CELTIC RELIGION – WHAT INFORMATION DO WE REALLY HAVE

INTRODUCTION

To begin with, lets first look at the sources available to us: There are quite numerous sources available, contrary to the usual belief that there is almost nothing actually there.

First, there are the archaeological sources. These are the only direct source for the prehistoric part of the religion we are talking about. The main elements we find here are sacred sites (being as well designed cult centres with a certain layout like the “Viereckschanzen” are, as there are “natural” places which were used to deposit offerings) and the findings and objects that came down on us (including as well bog bodies as graves, the objects found in ritual deposits and depictions of gods, most of which are from the time of the Roman occupation but which still tell us something about the Celtic religion)

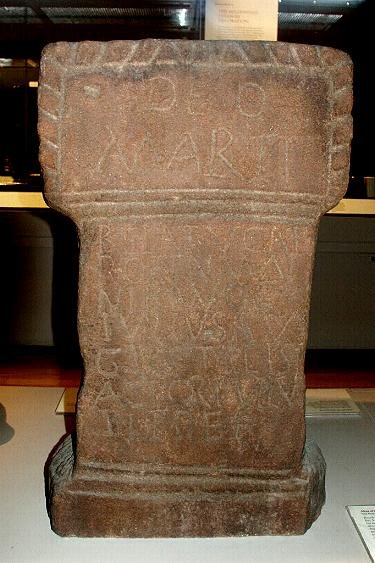

Second, there are the epigraphic sources, i.e. inscriptions. Most of those are from the time of the Roman occupation and as such their use is partly limited, however, some are autochtonous and preroman (mainly such from Southern Gaul and Spain).

Third, there are the historical sources from the diverse Roman authors. Although these are often biased due to the author writing, his knowledge, his political or other interests, the audience which he was targeting his writings at and other influences as later interpolations, they give us more or less first-hand information (at least almost contemporary information).

Fourth, we have the Insular literature, including early British histories (like those of Nennius and Geoffrey of Monmouth), sociopolitical geographies like those of Giraldus Cambrensis as well as Irish and Welsh tales. These sources are useable to get hints at how to reconstruct earlier religious concepts as well as to how Celtic religion might have looked in the Celtic countries not conquered by Rome during the first few centuries AD.

Fifth, we have the folk traditions in the countries which still are “Celtic”. Even though heavily Christianised, many a “pagan” deity of belief shows through these traditions, and as such these can be used to reconstruct missing parts as well.

These sources can be analysed and are additionally added by results of such fields as linguistics, comparative IE studies, comparative religious studies and general history, which all help by providing explanatory possibilities and construction and development models and possibilities.

I will now start this look at pagan Celtic Religion with a survey of what we know about what we would call “priestly” functions more or less.

RELIGIOUS FUNCTIONS

When thinking of Celtic religious functions, the first thing that comes to ones mind is doubtlessly the “druid”. In most of the literature, and not only the popular but a good deal of the scientific one as well, “priest” is equated with the term “druid” when talking about the Celts. However, this is a gross simplification. There’s definitely more to Celtic religious functions.

DIFFERENT RELIGIOUS FUNCTIONS

To start with, definitely the term druid is, to a certain extent, also a catch over term for all the Celtic religious functions., Caesar for instance, seems to use it in this kind in his excursus on the Gauls in his De Bello Gallico, when he writes: (BG VI, 13-4) “To return to those two classes: One of them is the class of the druids, the other one those of the knights. The druids are concerned with the divine worship, the due process of sacrifices, public and private, and in the interpretation of ritual questions … In fact, it is they who decide in almost all disputes, public and private …”.

On the other hand, the term druid is also used to describe a specific religious function. We can at least identify one other religious function, probably even more. For this, we can look at Strabo (IV, 4) quoting Poseidonius: “Among all the tribes, generally speaking, there are three classes of men held in special honor: the bards, the vates and the druids” (B/ardoi te kai\ Oua/teis kai\ Drui/dai). This gives us at least the vates as a second religious function, and it is possible that the bards are to be considered as a religious function as well.

Additionally, it is worth noting that for all these three classes we have equivalents in the Irish literature, where we find, additionally to the druid (Ir. drui/ Gaul. *druids) the fai/th (greek oua/teis, Gaul. *vatis) and the bard (greek ba/rdoi, Gaul. *bardos). Added to these in the function of interpreter of “rectus” (law), which would, if we follow Caesar’s description above, as well fall into the “druidical” functions, would be the Gaulish “vergobretus” (supreme magister), which contains the same root as the Irish “breithem” (judge). Additionally there is the Irish “fili” (seer, poet, priest), whichs gaulish cognate would be “*velits”, a cognate of is attested as a name for a Germanic seeres, “Veleda”.

This now leaves us with the following terms: Druid, Vates, Vergobretus, Bard, and perhaps fili.

Let us take a look at what their jobs were.

DRUID

The specialised function of the “druid” is described in Strabo IV, 4 as the science of nature and moral philosophy (pro\s te physiologi/a kai\ ten ethiken philosophi/an). The term “druid” itself is probably derived from IE *dru-uid- “highly wise” – which might be the reason for why it was also used as a catchover term for all the religious functions.

The specialised functions may allow us to assume that the druids in fact are the class who worked as medics and who were knowledgeable in herbal lore as described by Pliny the Elder. A grave of such a “druid” we know from the cemetery of Pottenbrunn, object 520, which contained the burial of an adult male of the early La Te\ne Period, which carried, additionally to the usual equipment, a medical instrument and a propellor-shaped bone object of unknown function, which could be an item used in rituals.

VATES

The function of the vates is described by Strabo as “interpreters of sacrifices and natural philosophers” (hieropoioi\ kai\ physiolo\goi). This fits quite well with what we know of as the function of the Irish fa/ith, whose job was to carry out the divinations. The description of Strabo allows us to assume that also the vates were the diviners, and as such probably also the calender of Coligny falls into their field of work (the Claender has been interpreted as a solar/lunar predictor by Olmsted), so the vates would be the ones who were the astrologers and mathematicians amongst the “priests”

VERGOBRETUS

We know little about the actual function of the Vergobretus, of whom we only have one short notice in the ancient literary sources which only gives us that title. However, as the term has the same root as the Irish breithem, whose function we know was judging in lawcases, we may assume that the Vergobretus was a similar function. As Caesar reckons the judging in lawcases to the druidical functions it can be assumed that it was a “religious” function as well.

BARD

Not much has to be said about the bards. Strabo (IV, 4) describes them as “singers and poets” (hymnetai\ kai\ poietai\), which fits quite well with what we know about the Irish bards. As a possible etymology for *bardos could be derived from the IE root *gur-d(h)o-s which is translated as “Praise Giver” this function could have been religious as well.

WHAT ELSE WE KNOW

Well, actually not much. We do not know which of the above if any carried out which of the rituals we know or can guess at. However, we know that, according to Caesar (BG VI, 14-2), “Many young men assemble of their own motion to receive their training; many are sent by parents and relatives. Report says that in the schools of the druids they learn by heart a great number of verses, and therefore some persons remain twenty years under training.”. Additionally, as well according to Caesar (VI, 13 and 14), they usually do not participate in wars, they don’t have to pay taxes, they elect for lifetime one out of their midst to be chief druid (more or less the druid pope), a position which is very honourable and therefore sometimes it is, if no decision can be found, even fought about with weapons.

CELTIC GODS

One of the most often cited statements about Celtic gods is that we have over 300 of their names that came down on us, while we know actually almost nothing about their functions. With this statement, usually the idea is transferred that the Celts had an unbelievable large pantheon which consisted mainly of local gods and demigods, with only a few if at all gods in common. However, this is probably a misinterpretation due to lack of knowledge.

THE SYSTEM OF THE CELTIC PANTHEON

A number of differing theories have been issued about how the Celtic (and, most often the common IE pantheon) might have been structured. The main theories follow the Dumezilian system, which postulates a tripartite structure where one part of the gods is the “warriors”, one the “agroculturalists”, and one the craftsmens” gods as the common system behind the IE panthei. However, this system has been often questioned. One of the most interesting new interpretations is the theory lately issued by Garrett Olmsted (The Gods of the Celts and the Indoeuropeans, Archaeolingua vol.6, Budapest 1994). He keeps the tripartite system, but offers a new interpretation of the functions of the gods of the different parts in assigning them to three mythical “realms” which he, for simplicity, calls Upper, Middle and Lower Realm (which is probably best visible in the Norse mythologies with Asgard, Midgard and Niflheim as Upper, Middle and Lower Realm and in the Vedic System which says that 11 gods dwell in the heavens, 11 on earth and 11 in the water), which however could be called Sky, Earth and Water. A good hint at such a system could be found in the diverse kinds of offerings used by the Celts: Cremation as sacrifices to the Upper Realm gods, Burying in the Earth as sacrifices to the gods of the Middle Realm and Deposition in Water as sacrifices to the Lower Realm gods.

THE NAMES OF THE CELTIC GODS

Well, I already mentioned that we have over three hundred names for Celtic gods. Lugos, Toutatis, Taranis, Cernunnos, Esus, Sequana, Brigantia, Epona, Matrona, Noreia, Eriu, Govannon, Belenos, Mabon and so on. It has been, for a long time, considered that the Celtic pantheon was regionally split up, that Noreia was a tribal goddess for the Norici, Sequana a tribal goddess for the Sequani, Eriu a tribal goddess for the Erenn. This also seems to be true, but only to a certain extent. As far as we can say by now, the Celtic gods had a lot of variants, the most we can find here are local but it is also possible that some were functional.

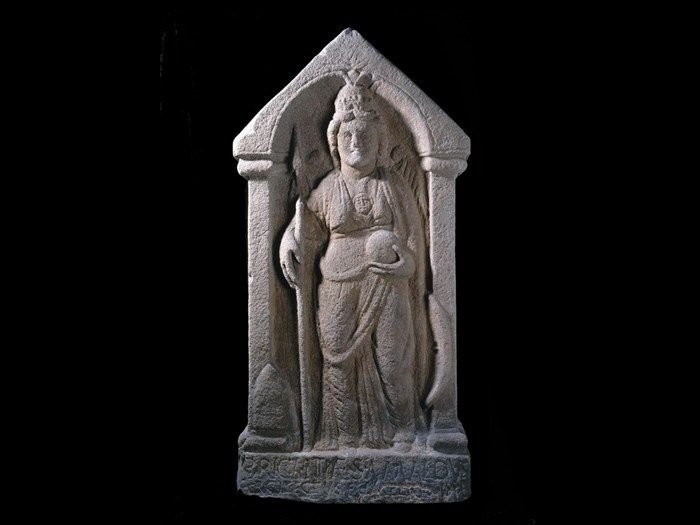

This is nothing surprising in fact, if we look at other IE pantheons we find that most gods in most pantheons have numerous, local and functional, bynames and names. The Greek god Zeus had multiple names, as is true for all the other greek gods. Iuppiter is also known to us as Dispater, and under numerous other names. The Hindu gods all have multiple names. The same is true for the Germanic gods. And if we look at the Gallo-roman inscription in which most of the Celtic god names have been brought down to us we find, not really surprising, that Mars is mentioned with over 50 Celtic god names, as Mars Toutatis, Mars Ambiorix and others, while Apollo is going along with Grannos, Belenos and others, while Taranis and others are attributed to Iuppiter.

Given this, it is most likely that the names of the Celtic gods that came down on us, are, for the most part, the local and/or functional bynames of gods whose “real” names probably were kept secret or which blend in with the bynames. Only two gods can be identified almost everywhere, being the god Lugos (Irish Lugh, Welsh Llew), whose name we find from Spain to Germany and probably even further east, and the mother godess (matrona), of which we know her functional name, i.e. mother, (old Gaulish matrona, Welsh Modron), and to which a number of the female names we have can be atrributed (Sequana, Noreia, Brigantia and probably as well Eriu and Boand, and additionally we have some “mothergodesses of places” like the Matronae Lugdunensis or the Matronae Treverorum).

GODS AND THEIR FUNCTIONS

Now lets take a look at the more important godly functions

THE SKY FATHER

More or less, the Sky father is the god we are used to refer to as “the head of the pantheon”. This god is probably derived from a common IE god named *Dieus-pater, translated as “Skyfather” – and is quite easily detectable in Greek Zeus Pater, Iuppiters byname Dispater and the the Vedic Dyauspita. In the Celtic World this function is most probably fulfilled by the Ollathair (Great father), the Dagda, whereby the Ollathair seems to be a reminiscent of the *Dieus-pater, although its best cognate is found in the Germanic Odin “Alfodr”.

The function of this god is that he is, usually, the progenitor of all other gods together with the Earth Mother.

Depending on the religion this god is also the head of the pantheon, or at least his father or grandfather and often also the god of thunder and lightning. It seems that this deity is the Dagda in the Irish mythology, while Gaulish mythology he seems to have been called Taranis (“the Thunderer, a cognate term to the Germanic Thorr from the IE root *tn-ro-s).

THE CONTROLLER OF THE LOWER REALM AND HIS CONSORT

This god usually is the one who is in charge of the otherworld and/or who is ferrying the dead to there. The Gaulish name for this god is “Sucellos” (the good striker), and he is equalled by Greek, Etruscan and Roman Charon. He is usually depicted with a great hammer and a dog by his side, and has a consort called Nantosuelta (either translated as “sun-warmed valley”, or as “who makes the valley bloom”, the second being suggestive of the Irish Bla/thnat, probably meaning “Little flower”, and Welsh Blodeued “Flower-faced”). We also see here a close parallel to the consort of Hades, Persephone. The dog which resides beside Sucellos usually could be an equivalent to the Greek Cerberos, the Hell-Hound. Equivalents in the Irish legend can be found in the Relationship between Curoi Mac Daire and Blathnath (Cu Roi actually meaning “Hound of the Plain”), especially given the fact that Curoi also appears as the churl in the beheading game in the quarrel about the heroes’ portion in Fled Bricrenn, parallels can also be found in the Welsh Mabinogi in the story about Llew and Blodeued. The apparent similarity of Arawn from Annwn with his beautiful wife and his red-eared dogs to the position of Sucellos is also worth a note.

DAYTIME AND NIGHTTIME CONTROLLER OF THE UPPER REALM

The upper realm control seems to have been split to be fulfilled by two gods, characteristically one of them is One-eyed, the other one-handed. This is true for Vedic Va/runah and Mitra/h as well as for the Germaic pair Odin and Tyr.

The Celtic equivalents for those gods are quite apparent. If we look at Cath Maige Tuired, one of the most important texts for Irish mythology, we see Lugh, the one skilled in all arts, as closing one eye while cursing the enemy Fomorians, and the equaling of Lugh with Gaulish Lugh is not only apparent but unavoidable, as Caesar tells us that the Gauls credited Mercurius (whith which Lugos is equated by the Romans) with the invention of all arts. As Lugh`s name is probably derived from a Celtic root *lug with the meaning “burn, enflame”, we can possibly see the daytime Upper realm controler in him. If we add to this the festival of Lughnasad we could assume that he was also the controller of the summer half of the year.

His mythical twin, the one who was the ruler before Lugh, is in Cath Maige Tuired the (formerly) onehanded Nuadu, which we have equalled in the British deity Nodens. In the Gaulish Context this deity seems to have been identified both with Mercurius and Mars by the Romans, thus being more or less the “kings god” and the “god of the tribe”. Here we probably would have to set most of the Mars-connected gods like Toutatis, Vellaunos.

THE YOUTHFUL-SAVIOUR-CHAMPION

Another function is the one of the youthful-saviour-champion. This role is fulfilled by Cuchullin in the Irish texts, and mixes to a certain extent with the function of the Nighttime Upper Relam controller. This god is the warrior champion of the tribe, probably also the god to whom the diverse known Celtic warrior bands (like the Gaesates) would pray. He is the one who protects the cattle of the tribe, the one who goes into battle frenzy, who fights naked. His Gaulish equivalent probably would be Esus.

EARTH MOTHER

The Earth mother (surprise, she actually exists in Celtic mythology). It is usually this godess which was, together with the Sky father, parent of all the other gods. This godess appears as a separate godess in some IE pantheons (for instance Gaia in the greek mythology), but also can meld with other female godesses, most often with the female Upper Realm godess. In the Irish mythology s separate Earthmother figure seems to be preserved in the figure of Danu and Tailtiu.

She was usually also the mother of three goddesses associated with rivers or springs which are the female goddesses of the Upper, Middle and Lower realm.

THE GODESS OF THE LOWER REALM

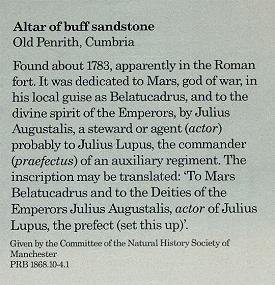

The goddess of the Lower Realm seems to have had a cowlike nature. It was probably called *Guououinda “White cow” (from IE *guou- + *uind-), *Matrona “Mother” (from IE *mater) or *Mororegni “Great Queen” (from IE *moro- + *regni-) She was also capable of shifting her form to an eel, snake, serpent or wolf, more or less the animal goddess. Additionally, she seems to be one of the aspects of the “goddess of sovereignty”. Her Gaulish names seem to have been S(t)irona “Heifer”, Damona “Cow”, but also Brigantia “the High, the exalted pure one”, Rigana “the Queen”, Matrona “mother”, but also Sequana “the Flowing” and Bovinda “white Cow”. Her Irish equivalents are for instance Boand (the Irish form of Bovinda), Brigit (equivalent of Brigantia) and Mo/rri/gan (the Irish version of Rigana). Her Welsh equivalent is Mordron (the mother).

Through intercourse with the skyfather this godess begets a god named “son”, who later marries his aunt, the godess of the middle realm. This son is the Gaulish *Maponos “Son”, in Welsh this is his cognate *Mabon “Son”, and, as expected, Boand is the mother of the Irish Mac ind O/c “young Son”. This god seems to be associated with fire.

THE GODESS OF THE MIDDLE REALM

The godess of the middle Realm apparently had the byname *Medhua “Intoxicatress” (from IE *medhu-). She seems to appear human in form, and definitly is also part of the “godess of sovereignity”. Her Gaulish name probably was *Meduana “Intoxicatress” or *Comedova (same meaning), and possibly also *Aveda “the flowing (Water)” Her Irish form is known as Medb or Aife (one of Mebd’s bynames).

This godess also has a son with the skyfather, called *nepots “Nephew” (alternatives *Nepotulos, *Neptionos) or *Nebhtunos “God of Waters”, or Irish Nechtain-Freach (the son of Medb), who later marries his Aunt, the Lower Realm godess (as Nechtain does with Boand). This god seems to be associated with water.

THE GODESS OF THE UPPER REALM

This godess is usually depicted as a horse. Her Gaulish name is Epona “Horse Godess” (from IE *ekuo-na), but she has as her bynames also the names *Rigana “Queen” (See also above for the Lower Realm godess) and possibly some others like ?Catona? “Battle Godess” and ?Imona? “Swift One”. Her Irish equivalent is Macha (which is also called Rigana “Queen”and Roech “Great Horse”, essentially a cognate of Epona). The byname ?Imona? of Epona could also explain the name Emain Macha, as ?Imona? is cognate with Emain (from *Imonis). Her Welsh equivalent is Rhiannon “Queen” (from *Riganona).

The name Macha may also indicate that here we have a melding of the Earth goddess with the Upper Realm goddess (see Latin *Maia “the Great, the Mother but also Sanskrit *Mahi “the Earth”).

This goddess as well is part of the “Goddess of Sovereignty”.

A FEW THOUGHTS ON THE “GODDESS OF SOVEREIGNITY”

As we have seen above, all those four goddesses are very interwoven in their functions. In fact, it is questionable if they are to be considered as separate godesses at all, or if they are not all only aspects of the Earth Mother/Godess of Sovereignity complex. Simply said, this is not decideable at the moment. It is also possible that due to the very scarce evidence and a constant intermixture, these goddesses became, even though separate goddesses, mixed to a certain extent by the Celts themselves.

THE GOD OF THE TREE FRUIT

This god is depicted as a bull. It is a twin god as far we can say, who has a white and a black form. The two twins seem to be fighting each other, starting out as humans and going through a series of shapechanges until finally, when both are bulls, the dark one rips the white one apart besides a sea. Its gaulish names are Tarvos Trigaranus “Bull with three cranes”, Tarvos “Bull” or Donnotaurus “Black bull”, the last one being a cognate of Donn Tarbh, another name for the Donn Cuailnge, who fights the Finnbenach “White horned one” in one of the preludes rto the Tain, also going through the shapechanges. In this, this figure fits with the Avestan Tistrya and Apaosa and, more perfectly even, with the Greek Zagre/ous-Dio/nysos.

THE GODESS OF WAR

Well know as a triplicate goddess from Irish mythology in the forms of Mo/rri/gan “Great Queen”, Nemain “Battle Frenzy” and Babd “Crow”. These three godesses are also refered to as the tres Mo/rri/gna “The three Great Queens”, therefore the Mo/rri/gan may not be identical with the Lower Realm godess, but also these might be three other aspects of the tripartite godess/three godesses that are responsible for the respective realms. The three battle godesses can shift into the form of a raven.

At least the Babd, who is also referred to as Babd catha “Battlecrow”, also in this form has a cognate in Gaulish gods names in [C]athubodva.

THE GOD OF ORATORY – THE CELTIC HERCULES

Apparently there existed a god in Gaul named Ogmios who was equated with the Roman Hercules as statet in Lucianus’s Dialogi Deorum (Hercules 1,7). This god is cognate with the Irish Ogma mac Elathan of the Tu/atha De/ Danann in Cath Maige Tuired, who is refered to as the champion of the TD and credited with the invention of the Ogam alphabet. He seems to have functioned as a god of oratory as well, Gaulish coins depict his audience as tied by silver chains to him which connect his tongue with their ears.

DEA LOCI – GODESS OF A PLACE

Additionally there existed goddesses which were “place-specific” in that they were seen as protectoresses and/or mothers of certain places. They are considered to fall in the group of Gaulish Matres, Matrones. We know such godesses for instance for *Genava (todays Geneva in Switzerland), Vienna (todays French Vienne) and numerous other places. A function of the Irish Macha in that kind for Emain Macha is also likely.

SPRING “NYMPHS” – GODESSES OF SPRINGS

There also exist numerous goddesses responsible for springs. We know of an *Acionna “?Water Godess?”, *Arvolcia “the very Wet”, *Cobba “Prosperity” and others. Equal functions were probably fulfilled by the godesses after which rivers were named like the Sequana, Matrona, Boand. We know for instance that at the spring of the Sequana offerings were made to that goddess.

WOOD “NYMPHS” – GODESSES OF THE LANDS

Equal to spring goddesses we also know of goddesses which were attributed to certain parts of the countryside. For instance we know of a goddess *Ardbenna “Goddess of the Ardbenna, the High Hills”, whose name still is clinging to the Ardennes forest on the German/French border and similar.

THE GENII – LESSER GODS / SPIRITS

The last type I’ll be mentioning here are the socalled Genii, sometimes also know as Genii cucullati “Hooded Spirits” which could have had numerous functions. We know of Genii of the “Neighbourhood”, Gaul. *Contrebis which is probably cognate with Irish contreb “community”, Genii of the family, Gaul. *Vinotonos from the Celtic stems *veni- “family” and the cognate of Irish tonn “wave, surface, land, earth, skin” as well as placename genii like Artio “god of the Bear (forest)”, *Alisanos “god of Alesia”, *Brixantus “god of Brixantion”, but also for tribes or their subunits like *Allobrox “God of the Allobroges, *Menapos “God of the Menapii”.

SACRED PLACES

Basically, we can discern two kinds of places “sacred” to the Celts. First, we have the natural sacred places and, second, the artificial sacred places (called “sacred monuments” from now on).

NATURAL SACRED PLACES

It is obvious from diverse archaeological findings and finds that a number of natural places had a sacred character to the Celts. Noteworthy is here, that basically all those places have an aspect of liminality.

SACRED PLACES IN CONNECTION TO WATER

The kind of sacred place most often used by the Celts (at least seemingly), is one that has something to do with water.

SACRED SPRINGS

The first kind of sacred places connected to water, and probably also one of the more important ones, are springs. As we have already seen while dealing with the gods, we know quite a great number of Celtic “spring nymphs”. This is mirrored by archaeological finds in springs. Some of the most important Celtic hoards have been found in such a situation, like the spring find from Duchcov, Chech Republic, in the springs of the Seine (the Gaulish Sequana), but also in the springs of Roman Aquae Sulis, tody Bath in England. In many cases, these are springs that have curative powers, and in the cases of the springs of the Seine and Bath it is also visible from the archaeological finds that the curative power of the spring and its related god/godess were consciously sought. In the Seine springs, for exaple, there have been found numerous models of human body parts from various materials, which can be interpreted as offerings to the godess Sequana who should cure the depicted body part.

This function of springs or wells is also hinted at in Cath Maige Tuired (123), where the Physician of the TD heals the wounded in a well, upon which he together with his two sons and his Daughter has chanted spells and in which he had cast all herbs to be found in Ireland.

SACRED LAKES

That lakes were places where contact to the “otherworld” was possible is well known from a lot of the epics. That some of them were considered as sacred places as well is also deductible from archaeological findings like the famous Lynn Cerrig Bach hoard, where a lot of items had been cast into the lake. An equal interpretation has also been brought forth for the name giving site of the La Te\ne Culture, La Tene at lake Newchatel, Switzerland, even though lately this has been questioned due to another finding at the point where the Ziehl (a river) flows out of the lake Neuchatel, where obviously a bridge was destroyed during a flood catastrophe while a lot of persons where on it, is the La Tene finds could have come into the lake for the same reasons.

SACRED RIVERS

That rivers had a certain sacred aspect is obvious from the fact that a good number of them take their names from Celtic gods, be it the Sequana, the Matrona, the Boyne or the Danube. Hints from archaeology towards offerings can be deducted from isolated findings of prominent standing, like the Battersea shield, that was recovered from the Thames river.

SACRED BOGS

That also boglands could have had “sacred” aspects is also likely. A hint to this can be found in the finding of Lindow man, a bog body discovered in Lindow Moss, England, of a man in his mid-twenties that was killed in a threefold manner (the kind of death also ascribed to some of the more famous British magicians/poets/druids like the Southern Scottish Lailoken or Merlin).

SACRED PLACES IN CONNECTION TO THE EARTH

We know little of sacred places that have to do with the earth, but that such existed are likely. It is, however, hard to decide in this case if these were natural “sacred places”, as offerings at such places would probably have to have been interred in the earth, which wouldn’t happen naturally but had to be done artificially, most probably. However, a number of isolated hoards that were found in the open countryside, like the Snettisham hoard (more or less a connection of gold torcs), or hoards at the edges of settled territory as they are known from Bohemia, for instance, could be interpreted as such offerings.

An equal interpretation is possible forsome skeletal finds (most often of females) in the gate area of some of the oppida, the fortified sites of (mainly) late La Te\ne dating. These skeletons are usually found below the walls in the gate areas and look very much like human sacrifices to protect the gate.

Probably also the sacred grooves of the Druids, the so called Nemeton or Drunemeton as related to us by the ancient authors, fall into this category.

SACRED PLACES IN CONNECTION TO SKY (OR EARTH, TOO)

The last group of natural sacred places are those which are most probably connected to the Sky (even though a connection to the Earth is also possible). Into this category fall sites like the Pass Lueg, Austria, on which a Celtic Helmet (one of the most famous ones as it is the one depicted on the Gauloise cigarette packs) was found, or maybe also the hoard of Erstfeld, Switzerland, which is at the foot of the Great St.Gotthard pass over the alps. These places could have been, like Greek Mount Olympus, been connected to the skies (due to their relativly high altitude), something which could equally be true of such remnants like the “Vierbergewallfahrt” (four mountain pilgrimage) in Carithia, Austria, or the Croagh Patrick tour.

SACRED MONUMENTS

The second group of sacred places are the sacred monuments. Here we can also distinguish between some different groups.

ANCIENT MONUMENTS

That ancient monuments were considered sacred places is beyond any doubt from the Irish and Welsh tales. One only has to think of the Beliefs connected to places like Newgrange (Brug na Boinne). A hint towards a similar belief of the ancient Celts can be found at the site of the huge tumulus of Hochmichele, Germany, where a Viereckschanze (see below) was erected directly besides the late Hallstatt tumulus.

VIERECKSCHANZEN

The second type of sacred monuments are the socalled “Viereckschanzen”. These are roughly rectangular wall and ditch constructions that appear in the La Te\ne period from middle France to Eastern Austria, covering more or less whole of the celtral Celtic area. Inside of these rectangular wall and ditch enclosures, which also quite often had elaborate gate constructions, there often appear deep pits which in some cases still contained wooden statues of “gods” and a number of offerings. Equal pits, but without the surrounding wall and ditch constructions, have also been found on the British isles. Sometimes also small houses appear inside these Viereckschanzen, which in some cases appear to be the predecessors of later Gallo-Roman temples.

TEMPLES INSIDE OF OPPIDA

Still another type of sacred monuments, even though connected to the above group, are the temples that have on occasion been found in oppida, like in Manching.

GRAVES

It is also likely that the graves were considered to be sacred places. In some areas of ancient Celtic culture the graves were surrounded by fences, which makes them in some sort similar to Viereckschanzen. Even though sacred, these graves have still been often enough robbed by graverobbers only a few years after the burial. This may be explained by simple materialism (a lot of the grave goods probably had quite some worth), but could also be interpreted as raids on the otherworld as we know them from the Irish and British tales.

OTHER SACRED MONUMENTS

It is quite possible that there existed other sacred monuments as well. For instance it is quite likely from the Irish tradition that places like Emain Macha, Tailtiu, Cruachan and Tara were such sacred places. Although most of them also fall in the category of ancient monuments it is possible that there were also some permanent residents at such sites, in contrast to other “ancient monuments” like in Newgrange.

RITUALS

On rituals that were performed in Celtic Religion only very little information has come down on us. However, we can still guess at a few of those. Basically, we can discern between some different groups of rituals. First, there are rituals performed at the seasonal feasts. Then we know a little bit about transmigrational rituals (rituals falling into the field of changes in ones life – often also called initiation rites, which only incompletely describes this group as the death rituals have to be included in this field). Third, we know of some divinatory rituals. Fourth, we know of some rituals falling in the field of curative processes, i.e. the healing of wounds or illnesses. Firth, we know about some “magical” rituals. Finally, we have hints to some rituals which can’t be put into any of those fields.

SEASONAL RITUALS

We know basically of four great seasonal feast that were part of the Celtic Yearcycle (I will not go into detail as to how these were situated in the year in ancient Celtic times, look for this at analyses of the Calendar of Coligny – which I perhaps will treat separately at some time), namely (starting with the beginning of the year) Samhain, in the current calendarical system fixed to the first of November, Imbolc (today 1st or 2nd of February), Beltane (today 1st of May) and Lughnasad (in August, usually equated with Lammas). We can be certain that rituals took place at those feasts, however, we know only very little about them.

SAMHAIN RITUALS

Samhain is the “Celtic new Year”. Rituals performed on this day (or these days) probably were protectional (as the barrier to the otherworld was thin at that time) ones, and probably such remembering the dead. This feast is known already from ancient Celtic times, where it is called “trinoux Samonis” or “tritinoux Samonis”, more or less translateable as “the three nights of Summer”, probably not meaning that they took place in summer but denoting the final three nights of summer.

IMBOLC RITUALS

We know almost nothing about Imbolc rituals. The only hint is that it is also called Eumelc (first milking, more or less), so it probably included rituals which had to do something with milk.

BELTANE RITUALS

Well, there’s also not much known about Beltane Rituals. The feast had to do something with fire (its translation is “Fire of Bel”, Belenos being one of the Gaulish gods associated with Apollo which is probably a variant of the “Son of the Mother” god, the son of the Lower Realm godess who was associated with fire), there are hints that it also existed already in Gaul.

One of the rituals we know of taking place at that feast was that the animals, especially the cows seemingly, were droven between two fires. Probably this was a purification ritual, and rituals associated with fire which exist in some parts of Europe may be remeniscant of Celtic rituals. (Like the burning wheels who are run down a hill in a village in Germany on the 1st of May).

LUGHNASAD RITUALS

Lughnasad is also only attested for Ireland. It was a harvest feast probably, the rituals carried out at this feast probably centering about the marriage between the Earth godess and Lugh (See the feast of Tailtiu) with a lot of contests of skill and strength, probably.

TRANSMIGRATIONAL RITUALS

The next big group of rituals are the transmigrational rituals. We know little of them, but we can guess at the existence of some, starting with the ritual of name giving, over various initiation rites until adulthood was reached, the inauguration rites to kingship also fall into this category, and finally the death rites are a part of this complex.

THE NAMEGIVING

From various sources we can guess that a ritual existed with which the child was accepted into the community of “humans” more or less.

This can be seen in the Mabinogi for instance, where the mother of Llew has to be tricked into giving him a name and only then (and after three other “initiations” he is considered to be a man), but also in the fact that we do not find babies in Celtic graveyards usually. The youngest individuals to be found in Celtic graveyard usually are no younger that 3 to four years, approximately the time when they start to speak.

OTHER CHILDHOOD TRANSMIGRATIONAL RITUALS

What else can be guessed from the Mabinogi text is that there were still some other initiation rituals until one could be considered adult. We only have hints at such rituals for males, but it is likely that they also existed in similar kind for females. What these other initiations are for the male nobles (as Llew is) is obviously the initiations to weapons (which is paralleled in the boyhood deeds of Cuchullin) and that he gets a wife (also paralleled in the Cuchullin tales where Cuchullin is not allowed to marry Emer until he hasn’t had special training “initiation” with the famous Scathach – in course of this initiation, however, he is primarily sexually initiated – see also that his son stems from this episode).

RITUALS TO BE ACCEPTED INTO A WARRIOR-BAND

At these rituals can be glimpsed from the Finn saga. Here, acceptance into the Fianna requires the applicant to succeed in a test which has many ritualistic elements. As such “warrior-bands” like the Fianna are also likely to have existed in ancient Gaul (see to this the Gaesates), equal rituals probably existed to be accepted into these bands.

INITIATION TO KINGSHIP RITUAL

On this matter we probably have the best information of all the rituals existing in Celtic religion. However, these rituals seem to vary from place to place and in time. What is told to us about the inauguration ceremony in Ancient Gaul is that the king to be is lifted, standing on his shield, by his followers. The rituals connected to the kingship in Tara, however, require the king to be to sleep with the sovereignity godess (according to Giraldus Cambrensis who claims to have seen such a ceremony in Connacht this means the king makes sex with a white mare, which is slaughtered, its blood and flesh are put into a large vat in which the king to be bathes, which is then cooked and then eaten by the people who are at the ceremony) and has to fulfill a test by stepping onto the LIA Fail. In the kingdom of Dalriada the ceremony probably included the king setting his foot into a “footprint” and some other ceremonies as well.

DEATH RITUALS

Besides of the actual deposition of the dead body (be it inhumation, cremation or whatever method else), there were some rituals which we can grasp from archaeology that were connected to death. These included in almost any cases a big feast in the area of the graveyard, of which sometimes still diverse animal bones can be located in the grave area, including a piece of meat and a container with drink (most often probably beer or similar, but in some cases wine, especially for richer dead). Additionally there were put into the grave other gravegoods as well, most probably also pointing at a ritual process in which the items were put into the grave. This is especially visible in some areas of Celtic settlement in certain time periods, where the items put into the grave with the dead body are intentionally destroyed (often called “ritually killed”).

DIVINATORY RITUALS

Another large group of rituals we know of as used by the Celts are Divinatory rituals. Most of them are no longer reconstructable, all we know is that the druids were able to predict the future from bird flight and similar things.

SACRIFICES RITUALS

It is noted in historical sources that the druids could predict the future from sacrifices. To do this, they would kill an animal, or in cases of high importance also humans, and predict from their death-throws.

BULL-SLEEP (“TARB FESS”)

Another divinatory ritual known to us is the so-called Bull-sleep, in Irish “Tarb Fess”. In this ritual the faith (Gaul. vates) overeats himself with the meat of a freshly killed bull (usually with yellow skin) and then lays down to sleep on the hide of that same bull. During the sleep he then has a prophetic dream.

CURATIVE RITUALS

Curative Rituals known to us have already been shortly mentioned in connection to sacred springs. Obviously, the Celts attributed high curative powers (even the power of rebirth) to the water. Hints to this we find in the already quoted passage in Cath Maige Tuired as well as in items like the “cauldron of rebirth” (the Grail of the Arthurian tradition), as archaeology gives us hints in the findings of models of body parts in the springs of the Seine. Obviously, Rituals like immersion in “sacred” water and the offering of equivalent models if the injured body parts was used as a curative ritual (although we also know of surgery made by the Celts, up to the surgical opening of the skull, i.e. trepanation).

We also know a “curative” incantation as allegedly used by Miach, the son of Dian Cecht, to heal the severed Arm of Nuada, the king of the TD. It goes: “joint to joint of it, and sinew to sinew” (Cath Maige Tuired 33).

MAGICAL RITUALS

The last great group of rituals are what I will call “magical” rituals here, because I know no better term for it. Suggestions are, however, welcome.

COLLECTION OF PLANTS RITUALS

The first kind of ritual in this group is described to us by Pliny the elder in his historia naturalis, where he is also speaking about curative plants used by the Druids and how they are acquired. This is the source wherefrom the famous Mistletoe story stems, and from which is usually deducted that the Druids wore white clothing (which I personally very much doubt). Pliny discribes how the druid puts the right arm through the left sleeve of his clothing and cuts, with a golden sickle, the mistletoe, which is caught in a white cloth. He describes rituals to collect some other plants as well, which include jumping on one leg around it in the lefthand direction.

BLESSINGS AND CURSES

Also falling in this group of rituals are the blessings and curses. Usually, they invoke a god to do something to somebody else, and are usually engraved into permanent material that is deponated somewhere (for instance lead plates). There are some quite nice curses on them in fact.

OTHER RITUALS

Finally, I take a look at some rituals which cannot be put into the above groups (at least not very well).

THE TEMPLE UNROOFING RITUAL

From the druidesses of one of the French channel islands we know of a yearly ritual, in which they unroofed their whole temple and then set up a new roof in one day. If one of the druidesses let fall what she carried of the roof, so it is said, she would be torn to pieces by the others. In fact, seemingly, the druidesses tried to make each other (or maybe also one of them that was chosen to previously) let fall pieces of the roof.

GENERAL SACRIFICES

In many of the sacred places we know of depositions of items, which have to be called “ritual depositions”. During their deposition definitely rituals were carried out, in some cases also including intentional destruction of the sacrificed items.

HUMAN SACRIFICES AND THE THREEFOLD DEATH

Finally I come to the human sacrifices. These (as already seen in the Temple Unroofing Ritual, which seems to include such a human sacrifice), definitely also had ritualistic components. We do not know much of them, but we have at least one such ritual that can be reconstructed, the so called “threefold death”. This means that the victim dies of three reasons at the same time. In the archaeological material we can see this in case of Lindow man, the bog body from Lindow moss in England, which was killed in such a ritual. As far as it can be reconstructed, Lindow man had been hit in the head (with probably an axe), however, not strong enough to let him instantly die. He was strangled with a Garotte, however, only as far as this would not have caused instant death. After these two “killings”, he was thrown in a pool in Lindow moss, face downwards and unconscious, probably, so that he as well drowned. So he died a “threefold death”.

Similar deaths through three simultaneous reasons are for instance also told about Merlin, and about the Southern Scottish “wise man”/bard/druid Lailoken, who allegedly fell off a cliff onto a spike standing out of a river, coming with his head under water so that he died from the fall, from the spike and from drowning.

This connection has led to the assumption by some scholars that in case of Lindow man we might have found a “Druid prince”.

It is also noteworthy that this threefold death could be interpreted as a death in all “Realms” as described for the gods. The Upper Realm (the skies/air) is found in the fall of Lailoken and in the strangualtion of Lindow man, the Middle Realm (the Earth) is found in the spike on which Lailoken lands and the axewound of Lindow man, and the Lower Realm (the Waters) are quite obvious.

HEADHUNTING

This practice is numerously attested by the ancient historians, the Irish tales and hints towards it can be found in archaeology as well. It definitely had a ritual meaning.

CELTIC RELIGIOUS BELIEFS

We know very little about the actual beliefs that were a part of Celtic Religion. Those very few hints we have are also not overly conclusive, but I’ll try to say as much as is possible.

BELIEFS IN CONNECTION TO CHILDREN

We know only very little about the beliefs connected to children. What we can definitly say is that children were not considered to be “real human beings” up to a certain age, probably up to the age of 2-3, approximatly the time when the child is starting to speak in consistent sentences. We have no children in the graveyards that are below this age, but we find them quite frequently in the settlements. Connected to this “becoming a human” seems to be the giving of a name to the child, as indicated in the 4th branch of the Mabinogi.

After this, however, the children appear frequently in the graveyards and are often adorned with that much jewellery that they probably had looked like chrismas trees when they were buried. Much of this jewellery is supposed to be of apotropaic (protective) function, to ward off evil spirits to which the children seemingly were thought of as being more likely to fall.

Apart from this we know little. We may safely assume that the passage from childhood to adulthood was connected with some beliefs, possibly also initiation rituals, but we know nothing about those but that they existed.

The only other belief (though this as well may have been a secular belief) that we know of is that it was seen as a bad omen if a father was seen together with his son who was not already in the age of carrying weapons (according to Caesar). This might indicate a religious background for a system similar to the fosterage system known from the Irish, which also finds its remnant’s in the upbringing of Lugh by Tailltiu in the Irish mythological cycle.

APOTROPAIC (PROTECTIVE) BELIEFS

We can be quite sure that there existed apotropaic beliefs. This is not only indicated by the frequent “amulets” found in children’s but also adults graves, but also in the way in which much of the jewellery and weaponry was decorated. The images of animals and also human faces (in the typical abstracted Celtic art style) can be seen as “protective” symbols to ward off evil spirits.

That other similar beliefs existed is also confirmed by a passage in the Tain Bo Cuailgne, where we hear that it was geas (prohibition) to the Ulaid to drive with a chariot on a day where there already had occured technical problems with it (like the breaking of a wheel or similar).

Also interpretable as apotropaic beliefs are the rituals described by Pliny the Elder for the Druids when collecting certain plants.

CALENDARICAL BELIEFS

What we know about calendrical beliefs is probably the best documented part of the beliefs (in form of the calendar of Coligny). We can be sure that in ancient Celtic Religion the year was divided in two main parts, the Winter half (starting with Samhain) and the Summer half (starting with Beltane) (although some theories want to set Samhain in the middle of the summer half, but that is probably nonsense). The other two great feasts (Imbolc and Lughnasad), if they at all existed in ancient Celtic Religion, seem to mark the respective middle of the respective halves. Seemingly, the Summer and Winter half fought with one another (in form of a white and a black bull, probably, but possibly also in the form of some gods, look for this in the first branch of the Mabinogi where the enemy of Arawn of Annwn is called Hafgan [i.e. “Summer king” more or less]).

Additionally we know that the months and days had a “lucky” and “unlucky” quality (Gaul. *matos=good, *anmatos=ungood, bad). The Gaulish calendar divided the year into 12 months more or less with 29 and 30 days respectivly (and a month to make up for the lost days every five years), of which the 29 day months were considered “anmatos” and the 30 day ones were considered “matos”. There were, however “matos” days in “anmatos” months and vice versa. What exactly this lucky/unlucky connotation meant, and what result it had on actions taken is not clear, but we can be sure that such a belief existed.

Such a belief is also found in one of the episodes to the Tain, where Cathbad, when asked what this day is good for by Ness, mother of Conchobor, he replies with: For begetting a king on a queen

THE SPIRITS OF NATURE

That a belief in spirits of nature existed in Celtic Religion is relatively sure. The rituals used by the Druids to collect plants as described by Pliny the Elder can, as well as containing apotropaic elements, be seen as magic used to cheat the spirits of the plants collected (for instance putting the right arm, which is the “dangerous” one, through the left sleeve can be seen as a trick to make the plant believe it is safe until it is too late). Partly, these nature spirits may have become the small folk of the Irish legends.

If believes in such spirits influenced the daily routine in any way we do not know.

BELIEFS CONNECTED TO HEALING

We know little about the beliefs connected to healing but that it was performed by the druids. Seemingly, there were multiple possibilities like making offerings to spring godesses like we know from the springs of the Sequana, then there is the possibility that there were beliefs of dogs licking wounds (as indicated by the British god Nodens, who had a connection to dogs that were licking wounds of injured), but also surgery performed like trepanation (the opening of the skull) could have been connected to a special belief (especially if we remember that the head had a special place in Celtic beliefs).

Additionally it is obvious from various sources that curative powers were ascribed to some herbs/plants.

BELIEFS CONNECTED TO KINGSHIP

Of old Celtic kingship we know relatively little, but this can be made up by what we know from the Irish evidence. Obviously, the main belief in regard to kingship was that the wellbeing of the king reflected itself in the wellbeing of the land. A king that lost his perfect appearance reflected this back on the land as well, be he scarred or going that far that he had lost a limb. A physically “not perfect” person would not be able to be king, due to this connection. However, this “perfectness” not only was a matter of physical appearance, but also a matter of mental wellbeing. As such, a ruler had to be just, as injustice would immediatly fall back on the country. Additionally he wouldn’t be allowed to be greedy, because if the king would not give his gifts with open hands, so would nature not wield good crop.

BELIEFS CONNECTED TO GODS

We know little about that, except that diverse gods had diverse functions. Apart from that, we only can say that some members of the society would have a closer connection to one god than to most others, like the shoemakers would (and we know this from one of the Celtiberian inscriptions) tend more towards the god Lugos (which’s equivalent Llew we find as a shoemaker in the Mabinogi).

Apart from that we can be pretty sure that the “gods” were living in an “otherworld”, similar to the Irish belief, and were in some kind connected to the “mythical ancestors” of the people, which can be seen in the assignment of old huge gravemounds as their “palaces”, which is true in Ireland (see only the example of Newgrange), but also in Wales (Pwyll gets to know Rhiannon, his “otherworld wife”, i.e. the godess of sovereignity, while he sits on Gorsedd Arberth, a Megalithic Tomb), and we can assume something similar for the continental Celts (as seen in the Viereckschanze next to the gigantic gravemound of Hochmichele in Germany). Actually, these “gods” seem to have lived on this planet in the past, and only after their death in this world became “gods”. In this way it can be seen partly as ancestral worship.

OFFERINGS AND SACRIFICES

That offerings and sacrifices were deemed necessary is evident from their existence alone. What beliefs especially led to these practices (except the belief that important decisions for the future could only be gained by reading the future in the death of a human sacrifice) we do not know.

BELIEFS CONNECTED TO THE HEAD

As far as we can say the Celts had a special reverence for the head. This is evident from the ancient sources, where we are told that heads of enemies were kept as familiy treasures, and that such heads would not be sold for their weight in gold, as we can find it in archaeology, where we as well have monuments like the one in Roquepertuse, where a stone portal was adorned with human skulls as we have often enough separate skulls in the settlements and amulets made from human skullbones.

An equivalent belief can also be seen in the Tain, where Conchobar keeps the brain of one of his enemies conserved in Emain Macha, which is later stolen and used as a slingshot against him, which later causes his death.

That the head also had a special significance is also evident from the Mabinogi, where Bran tells his companions to severe his head and take it with them and after entertaining them for 80 years bury it in London with the face towards the continent to ward off any enemies (which could also be seen as an explanation for the human head depictions on artwork). BTW, this motive later becomes part of the early grail legend.

What belief it exactly was that was connected to the head (especially the severed head) is unknown, but it has often been speculated that the head was seen as the part of the body that contained the soul, so it could well be that the one who had the head of a person also had his soul.

MAGIC

That the Celts believed in some kind of magic is evident. The most obvious belief is the one in what in Irish is called “Geis”, plural “Gessa”, which could be best traslated as “Prohibition, Taboo”. Such gessa could be anything from not eating with three women to not hunting birds, but also could include tests in the kind of “it is geis for you to not return here until you have done this and that”.

AFTERLIFE BELIEFS

Much has been already speculated about the afterlife beliefs of the Celts, but almost all is based upon a short notice in Caesar’s De Bello Gallico, where he states: “The druids teach that the soul is immortal, that it moves from one to the other after death”. This has been interpreted as a belief in rebirth similar to the Hindu reincarnation belief. However, it is more likely that what was really meant was a belief in that the soul lives on in an otherworld.

BELIEFS CONNECTED TO THE CREATION/END OF THE WORLD

We know almost nothing about the pagan Celtic beliefs about the creation of the world and its end. It can however be speculated, that the creation was seen similar as in most other IE religions as the Eartch mother giving birth to the world.

On the end of the world we equally have almost no information. However, it can be guessed from statements as famous as “we fear nothing but that the heavens may fall down on our heads”, which we know was said to Alexander the Great by Celts on the lower Danube as well as it finds itself in the Tain as the famous last words of Cuchullains (foster)father, that there existed a belief that at the end of the world the heaven would fall down on earth