Contents

- 1 The Power of Air Photo Coverage: Unveiling the Layers of History

- 2 Further Resources on Air Photography and Aerial Mapping

- 3 Key Feature Markings in Air Photography: A Beginner’s Guide

- 3.1 Parch Marks:

- 3.2 Shadow Marks:

- 3.3 Why They Matter: Shadow marks can reveal the contours of ancient Earthworks, buildings, or other structures that have long since eroded or been obscured by vegetation. These marks are best seen during low sun angles, such as early morning or late afternoon, when shadows are long and dramatic.

- 3.4 Soil Marks:

- 3.5 Crop Marks:

- 3.6 Linear Features:

- 3.7 Geometric Patterns:

The Power of Air Photo Coverage: Unveiling the Layers of History

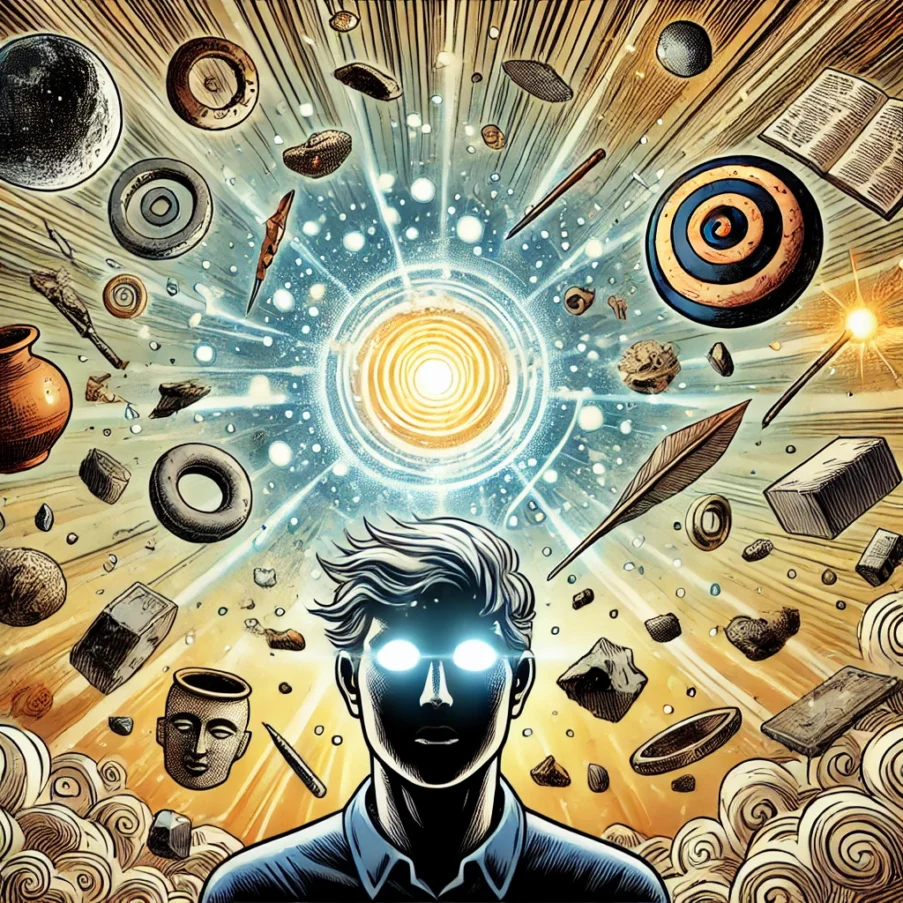

When it comes to uncovering the secrets of the past, air photography is an invaluable tool that offers a bird’s-eye view of archaeological sites and their surrounding landscapes. Whether taken by satellite, drone, or traditional aircraft, aerial photographs allow researchers to examine sites from unique perspectives, providing insights that cannot be easily obtained from the ground. These aerial images offer not only a snapshot of the site itself but also a larger picture of its context within the surrounding landscape—revealing connections to other sites, patterns, and relationships that may have been overlooked.

In this article, we explore the various methods of obtaining air photos, the benefits of using them, and why it’s essential to gather as many images from different periods as possible to create a detailed and comprehensive understanding of a site.

Why Air Photos Matter

Aerial photographs give archaeologists the opportunity to examine a site in its broader context—how it interacts with the landscape, nearby structures, and other historical features. They offer several key advantages:

Broader Context: Air photos allow you to see not only the site itself but also its relationship to the surrounding area. This can include proximity to rivers, roads, other archaeological sites, and natural features that might have influenced its location and function.

Site Discovery: Sometimes, features that are invisible from the ground, such as buried walls, ancient roadways, or ditches, can be revealed through differences in vegetation, soil, or topography that show up in aerial imagery.

Temporal Insights: By having air photos taken from different time periods, you can trace changes in the landscape over time, identify phases of occupation, and monitor the site’s transformation. This makes it essential to gather as many images from as many periods as possible—capturing not just the site itself but also how it has evolved within its environment.

Landscape Analysis: Aerial imagery can help archaeologists map out entire regions, showing how different sites and features are interconnected. This can provide clues about trade routes, regional patterns of settlement, and the broader structure of ancient landscapes.

Methods of Obtaining Air Photos

There are several ways to capture aerial photographs, each with its own benefits and applications. The most common methods include satellite imaging, drone photography, and traditional aircraft-based aerial photography.

Satellite Imagery: Satellite-based photography is often the most widely available and cost-effective method for obtaining air photos. Satellites provide high-resolution images of large areas, offering a comprehensive view of regions. These images are particularly useful for covering large archaeological sites or whole landscapes at once. The disadvantage is that the resolution may not be as high as that from drones or aircraft, but they provide valuable long-term coverage of an area.

Drone Photography: Drones have become an essential tool in modern archaeology, providing a flexible and cost-effective way to capture high-resolution images of specific sites. Drones are particularly useful for documenting smaller areas with great detail, allowing for the capture of aerial images from various angles and heights. They can be flown in low altitudes, providing the ability to focus on specific features and capture detailed imagery that satellite photos may miss.

Traditional Aerial Photography (Plane-based): Traditional plane-based aerial photography offers the advantage of covering large areas with a consistent perspective and high resolution. Pilots can fly at low altitudes to capture detailed images of a specific site, or they can take long-distance shots from higher altitudes for a broader view of the landscape. This method is often used for archaeological surveys, landscape analysis, and when precision in imagery is needed. The main disadvantage is the cost and logistical challenges of arranging flights, but the results are often unparalleled in terms of clarity and coverage.

The Benefits of Long-Distance Aerial Shots

In addition to low-altitude shots that focus on a site’s details, long-distance aerial photography taken from high peaks or surrounding mountains offers significant advantages:

Overview of the Region: From higher altitudes, you can capture expansive images that provide a holistic view of a site’s environment, showing not just the site itself but also its relationship with the landscape. This broader perspective is essential for understanding the site’s position in relation to natural resources, strategic locations, and trade routes.

Contextualizing the Site: Long-distance shots from high surrounding peaks help researchers see how a site fits into the larger topography—revealing important environmental factors such as proximity to water sources, defensive positions, or important cross-roads. These long-distance photos often reveal patterns of human settlement that might be invisible in smaller, localized images.

Landscape Evolution: Higher altitude shots provide a clearer understanding of the changes in the landscape over time. They can show the evolution of the surrounding environment and reveal how the landscape itself may have influenced the development or decline of the site.

Building a Picture Over Time

To gain the most complete understanding of a site and its surrounding landscape, it’s important to use air photos from multiple time periods. Changes in the landscape, construction of new roads, the growth or loss of vegetation, and even the impact of human activity over time can be traced using historical aerial images.

By combining historical air photos with modern ones, archaeologists can document the transformation of the area, uncover patterns that might not be visible otherwise, and uncover layers of history that span centuries. The ability to compare past and present photos provides a dynamic way to explore the long-term impacts of human activity on the landscape.

Your Aerial Adventure

Incorporating air photos into your exploration of local archaeology offers a deeper, more comprehensive understanding of the landscape and its history. Whether you’re looking at ancient sites, investigating hidden features, or simply appreciating the natural beauty around you, aerial images provide a wealth of information that can transform your study into an adventure. The relationship between the site and its surroundings becomes clearer, and each image adds another layer to the ongoing story of the land.

Further Resources on Air Photography and Aerial Mapping

- USGS Earth Explorer (Earth Explorer): Offers access to satellite imagery and aerial photos, with datasets covering several decades. A great resource for historical imagery and topographical maps.

- National Aerial Photography Program (NAPP) (NAPP): Provides aerial imagery of the United States for use in environmental and archaeological studies.

- UK Aerial Photography (UK Aerial Photography): The National Archives offer access to historical aerial photos of the UK, which can be used to explore changes in the landscape over time.

- Historic England: Aerial Photo Collections (Historic England): Historic England provides access to their archive of aerial photography, which is particularly useful for historical and archaeological research.

- Google Earth Engine (Google Earth Engine): Provides satellite imagery and aerial photography from multiple time periods, which can be accessed through their platform for free or with a subscription.

By exploring these resources and methods, you’ll have access to a wealth of aerial imagery that can enrich your understanding of local archaeology and the historical landscape. The combination of different types of air photos—whether satellite, drone, or plane-based—gives you a unique perspective on the world around you, one that allows you to explore both familiar and unknown landscapes from a whole new angle.

Key Feature Markings in Air Photography: A Beginner’s Guide

Aerial photography is a powerful tool for uncovering hidden features in the landscape, many of which are invisible or difficult to spot from the ground. Here’s a summary of the key types of markings and features that air photos can reveal, providing clues for those starting to explore the history of the land:

Parch Marks:

What They Are: Parch marks occur when differences in moisture levels in the soil—often due to the presence of buried structures like walls, ditches, or foundations—create variations in vegetation growth. These marks appear as distinct, often dark, patches of grass that are more stressed or withered compared to surrounding areas.

Why They Matter: Parch marks are particularly visible during dry conditions or in the summer months, when the buried features alter the moisture content of the soil, leading to visible differences in the plant life above them.

Shadow Marks:

What They Are: Shadows are cast by raised or sunken features on the ground, such as mounds, walls, or buried structures. In the right light conditions, shadows can highlight subtle variations in the topography that might not be visible from the ground.

Why They Matter: Shadow marks can reveal the contours of ancient earthworks, buildings, or other structures that have long since eroded or been obscured by vegetation. These marks are best seen during low sun angles, such as early morning or late afternoon, when shadows are long and dramatic.

Soil Marks:

What They Are: Soil marks are changes in soil color or texture caused by the presence of buried archaeological features. These marks are often visible when there are slight differences in soil composition that alter how the ground responds to rain, leading to changes in color or texture.

Why They Matter: Soil marks can indicate the presence of buried ditches, roads, walls, or even features like hearths. In some cases, these marks might also highlight the boundaries of ancient fields or settlement areas.

Crop Marks:

What They Are: Crop marks are variations in the growth patterns of crops caused by the presence of underlying features such as walls, pits, or foundations. These marks are typically visible in fields with crops like cereals, where different soil types (or disturbance by ancient structures) result in varied growth rates.

Why They Matter: Crop marks can reveal the outlines of buildings, roads, or other man-made features that are buried beneath the soil. They are particularly useful for identifying ancient settlement patterns, fortifications, and other large-scale structures.

Linear Features:

What They Are: Linear features refer to straight lines or tracks visible in aerial imagery, often indicating the remains of ancient roads, pathways, or boundaries. These lines might appear as subtle depressions or raised areas in the landscape, depending on the type of feature.

Why They Matter: Linear features can indicate ancient transport routes, boundary markers, or other man-made structures that once shaped the landscape. They can often be traced across wide areas and connected to other archaeological sites, revealing the larger network of human activity.

Geometric Patterns:

What They Are: Geometric patterns refer to regular, often symmetrical shapes visible in the landscape, such as circles, squares, or grid-like formations. These might indicate the layout of settlements, fields, or ritual sites.

Why They Matter: Geometric patterns can provide evidence of planned settlements, agricultural fields, or ceremonial areas. They help archaeologists understand how ancient societies organized their spaces and activities.