Contents

Site Details:

Hall Tower Hill and Wendel Hill - Barwick in Elmet

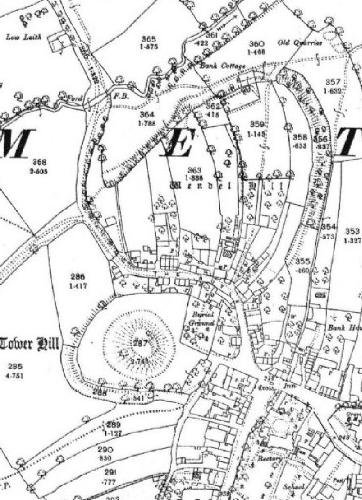

Air photo (W Yorks Metropolitan CC) and 1908 OS map entry for Barwick in Elmet, the later Bailey tower can be clearly seen, the larger enclosure of the earlier Iron Age fort can be seen.

The massive earthworks at Barwick and the continuation of the same profile alongside the River Cock to Aberford and beyond point to it being a place of importance as a large hillfort of some 15 acres. There were several hillforts in northern Britain when it was inhabited by a Celtic tribe called the Brigantes.

Description

"The scale and function of the earthworks, which may comprise a rampart, a ditch and a counterscarp bank, is massive and assumed to be defensive though large univallate hillforts may have been built on the sites of earlier non-defensive enclosures such as slight univallate hillforts. In area, large univallate hillforts vary between 1 and 10 hectares. Most large univallate hillforts were built between the fourth century BC and the first century AD, though a small number were built as early as the sixth century BC. Between 50 and 100 examples are recorded nationally, most occurring in southern England with a smaller number being located in central and western England and a very few being found in West and North Yorkshire. Common features of large univallate hillforts include one or two inturned entrances, internal quarry scoops or ditches, guardrooms and approach roads, while the interiors of large univallate hillforts reveal a high density of structural features such as roads, roundhouses, raised granaries, pits, drains and fence lines. These reflect the high status and permanent occupation of large univallate hillforts whose massive defences are also thought to have provided a deliberate reminder of the power of the inhabitants. Large univallate hillforts therefore provide an important commentary on the nature of settlement and social organisation in the Iron Age and are one of the rarer classes of monument belonging to the period. All examples with surviving archaeological deposits are considered to be of national importance."

Plan of the earthworks, drawn by H. S. Chorley, 1908.

"Motte and bailey castles are medieval fortifications of a type introduced into Britain by the Normans. They comprised a large conical mound of earth or rubble, the motte, surmounted by a palisade and stone or timber tower and adjoined by an embanked enclosure, the bailey, which contained additional buildings. Motte and bailey castles had several functions. They were strongholds, acted as garrison forts during offensive military operations, were often aristocratic residences and were the centres of local and royal administration. Built in towns, villages and open countryside they generally occupied strategic positions, dominating their immediate locality. Over 600 are recorded nationally, with examples from most regions. As such, and as one of a restricted range of early post-Conquest monuments, they are particularly important for the study of Norman Britain and the development of the feudal system. Although many were occupied for only a short time, they continued to be built from the eleventh to the thirteenth centuries, in some cases forming the basis of the stone castles of the later Middle Ages."

"The monument at Barwick in Elmet is a good and reasonably well-preserved example of a large univallate hillfort. It lies outside the main distribution and is one of only a small number outside Wessex whose internal area is above the middle of the scale of 1 to 10 hectares. Very little of the surviving remains have been disturbed, making it of great importance to the study of this class of hillfort. Equally important are the well-preserved remains of the motte and bailey castle."

Air photo of Barwick.

The Hall Tower

The massive earthworks at Barwick and the continuation of the same profile alongside the River Cock to Aberford and beyond point to it being a place of importance as a large hillfort of some 15 acres. There were several hillforts in northern Britain when it was inhabited by a Celtic tribe called the Brigantes. To the south-west of Barwick-in-Elmet was Almondbury, another large hillfort. To the north was Aldborough, a smaller hillfort, and further to the north was Stanwick, another large hillfort.

The late Dr Herman Ramm of York tells us something about these hillforts, set in the hills and valleys east of the Pennines. It meant that the Brigantes were divided into small groups and were more difficult to control than in southern Britain. Sir Ian Richmond in 1954 had placed Almondbury as the seat of Cartimandua, leader of the Brigantes at the time of the Roman conquest but this was shown later not to be the case and we must look elsewhere.

The Stanwick fortifications were identified by Sir Mortimer Wheeler as the fort from which Venutius, Cartimandua's former husband and successful rival, made his last stand against the Romans. It lies between the Swale and the Tees and it was well-placed for north to south communications and to control the northern Brigantes. Equally, it could deny control of the north to a power sited further south in the Vale of York, where logically we should expect to find Cartimandua's home base.

Herman Ramm says that if we look for a suitable hillfort in the Vale of York not too far from the later centre of Aldborough, then the stronghold of Barwick-in-Elmet is the obvious place, a large 15 acre hillfort.

Do not let us forget that this Barwick of ours was an important centre in the Ancient Kingdom of Elmet, which existed in the so-called Dark Ages between the collapse of Roman rule and the taking over of England by the Saxons.

Let us now move on to the time of the Normans in the twelfth century and what effect it had on Barwick. It was Ilbert de Lacy the Norman who erected the motte and bailey castle known as Hall Tower Hill on the southern end of the hillfort. This Albert de Lacy did the same works at Almondbury inside the hillfort there.

The writer and historian Wace, who was at the court of Henry II, says that the Saxons were defeated by the wonderful staff work of the Normans. He goes on to tell us that the Normans "sailed from S. Valeri with seven hundred ships less four and there were boats and skiffs to carry arms and harness and when they started the Duke placed a lantern on the mast of his ship that the other ships may follow and hold their course after it".

The Normans brought with them prefabricated timber castles and palisades with holes already bored to receive wooden pegs brought in large wood barrels, everything ready for assembly when they landed in England, so that before evening had set in they had finished a fort, which we call a motte and bailey castle.

The ditch of the motte encircled the bailey where there were stables, barns, kitchens and barracks. In Barwick, most of the bailey to the east of Hall Tower Hill has been built on and destroyed.

Research info

"It will now be appreciated that the evidence for the advance by Gallus is very uneven. When the sites for which there is no certain evidence are placed on a map (fig 36). the only certain route is that of Wall to Templeborough. If this was continued northwards, it could be seen as directed towards Barwick in Elmet, via Castleford (Lagentium). Only the forts at Trent Vale and the 'vexilation' forts at Newton on Trent and Rossington Bridge hint at any other possible forward movement at this period. It seems rather unlikely that Gallus would have thrust a single fortified route forward unsupported by a wider area control, but the question must remain open and the suggestion made above should only be considered as a guide or model for further work." Graham Webster, Rome against Caratacus, commenting on the possible Roman routes established during the rule of Gallus - AD 52-57.

Site Gallery

Gallery Empty