Contents

- 0.1 A short history of coal-mining in Coverdale

- 0.2 Ten inter-related places that tell the story

- 0.3 Using this for a landscape-traffic model

- 0.4 How documentary searches can illuminate the social-economic web of Coverdale’s mining

- 0.5 Mining-specific documentary sources you can mine (pun intended) for Coverdale’s coal story

- 0.6 Heritage sites that mirror Coverdale-style “hill coal” mining

- 0.7 Mine Safety – Why thin upland seams rarely suffered gas explosions

- 0.8 Documentary check

- 0.9 Comparison

- 0.10 Conclusion

- 1 How many people actually mined Coverdale’s coal?

- 2 Small Scale Mining, Poor Infrastructure

- 3 Coal-handling points linked to the Coverdale pits

- 4 Social life around Coverdale’s hill-coal pits (c. 1750 – 1914)

- 5 Conclusion – assumptions, caveats and the road ahead

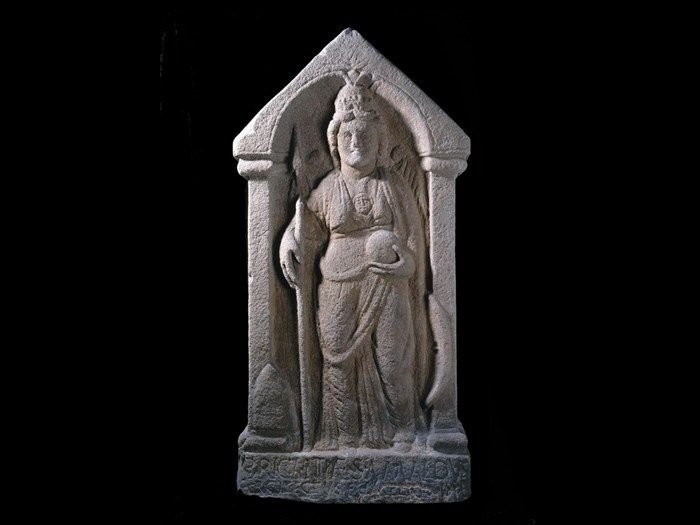

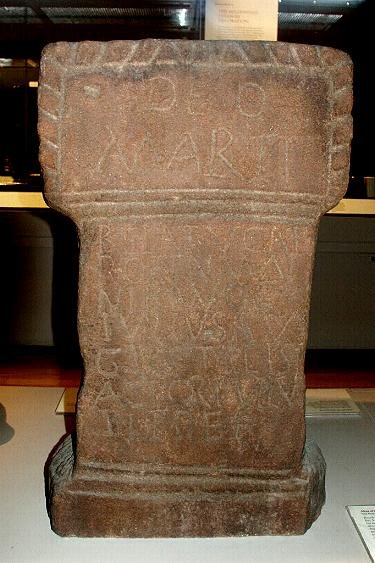

A short history of coal-mining in Coverdale

Coverdale never possessed the thick, profitable seams that powered the great Yorkshire coalfield; instead it sat on the very feather-edge of the Yoredale Series where thin coal bands (18 – 50 cm) lie between the well-known Limestone, sandstone and Shale rhythms.

From the seventeenth century every township on the dale floor needed small amounts of coal to fire hearths, limekilns and later dairy boilers. The nearest market collieries were over Wensleydale or down the Swale, so the dale folk repeatedly reopened their own moor-top outcrops. Workings were always small, seasonal and labour-sharing—farmers cut “hill coal” in winter, carted it home by sled or pack-pony, then returned to stock and hay in summer.

- Pre-1700 – documentary hints (Coverham manorial rolls) of “cole-garthes” on Great Low Moor; no fixed shafts.

- c. 1750-1815 – lime-burning boom to improve acidic pasture drives deeper “horse-gin” shafts on West Scrafton Moor; coal still only sold within Coverdale & Bishopdale.

- 1815-1870 – lead-smelting in upper Wharfedale inflates demand; several new levels driven under moorland blanket peat; estate papers show rentals to the Earl of Carlisle.

- 1870-1914 – West Scrafton Colliery Company (a five-man partnership) sinks the 110 m Engine Shaft and installs a portable steam winder; output peaks at c. 800 tons p.a. but collapses when rail-borne coal reaches Middleham.

- 1914-WWII – intermittent “home coal” cutting by dale farmers; last recorded load (one cart from Henstone Level) taken down into Carlton in 1936.

- Today – fragmentary remains: shaft collars, binges, gin-circles and a line of sunken trackways that still dictate sheep-fold positions and grouse-shoot access.

Coverdale Mine Workings, close to Coverham

| # | Place & NGR | What survives & why it matters | Relationship chain |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | West Scrafton Engine Shaft (SE 0642 8410) | Flagged collar, rubble gin-circle, two beehive coke ovens; deepest shaft (110 m) and hub of the 1870-1914 company. | Sent coal west to quarry limekilns at Coverhead (site 4) along the Scrafton Moor Track. |

| 2 | Great Low Moor Drift (SE 071 849) | Low Adit opening backed by spoil heap; earliest “cole-garth” referenced 1694; shale roof still sooty. | Earliest extraction fed limestone clamp-kilns at Agglethorpe (site 5). |

| 3 | Henstone Level (SE 051 829) | Stone-lined level, air-shaft mullion and shallow binges; last recorded working, packed in 1936. | Supplied winter coal to Carlton farmhouse boilers via Henstone Old Road that meets Thoralby bridleway. |

| 4 | Coverhead Limekilns (SD 995 836) | Twin draw-kilns (Scheduled Monument) that burned Scrafton coal and dale limestone, 1780-1830. | Bulked coal from Engine Shaft (site 1) on sleds; shows coal-for-lime linkage. |

| 5 | Agglethorpe Clamp-Kilns & Coal Yard (SE 084 866) | Grass-covered clamp platforms and charcoal scatter; estate map (1732) labels “Coalstead Close.” | Coal walked in from Great Low Moor Drift (site 2); earliest evidence for farm-scale lime dressing. |

| 6 | Swineside Horse-Gin Circle (SE 027 848) | Perfect Gritstone ring (9 m Ø) for horse Whim; shallow shaft depression in centre. | Probably rotated men and ponies with West Scrafton mine—work-sharing across townships. |

| 7 | Little Haw Inclined Level (SE 046 859) | Sloping gallery in crinoidal limestone, partly flooded, with iron dog nails; experimental 1840s attempt to gravity-haul tubs. | Aborted venture after Engine Shaft hit thicker seam—shows competitive prospecting. |

| 8 | Coal Road (Carlton Moor Ridge) (SE 071 876 → SD 965 836) | Hollow-way with coal Grit scatter; appears on the 1766 Jeffreys map as “Cole Way.” | Primary trans-dale pack-route connecting Moor pits (sites 1–3) to lower dale farms and the Coverham Priory grange. |

| 9 | West Scrafton Colliery Reservoir (SE 060 843) | Dammed peat gully; stone outlet culvert to Engine Shaft boiler pond. | Demonstrates shift from pack-animal to steam power and ties Engine Shaft to 1870–1903 steam ledger. |

| 10 | Lead-Smelting Route junction at Horsehouse (SE 077 852) | Medieval bridge and widened drovers’ lane where coal cart track meets Lead Lane to Wharfedale. | Highlights cross-industry linkage: Coverdale coal carted over Cover Head Pass to fuel Wharfedale smelt-mills 1820s-60s. |

Web of relationships (why treat them as a network?)

- Fuel–Lime nexus – sites 1, 2, 4, 5 show how thin coal seams underwrote the limestone-sweetening revolution in an acid upland.

- Shared manpower – Swineside (6) and Little Haw (7) illustrate township cooperation and speculative rivalry: miners rotated between pits depending on seam luck and farm workload.

- Steam modernisation loop – Reservoir (9) feeds Engine Shaft (1); when the boiler failed in 1903 the entire coalfield collapsed, proving systemic fragility.

- Inter-dale commerce – Horsehouse junction (10) maps the outward flow: Coverdale coal exchanged for Wharfedale lead bullion and later for cheap Durham pit-coal once the railway reached Leyburn.

- Landscape legacy – All ten lie on connected hollow-ways or moor tracks still visible and walkable, making them ideal for a heritage trail or GIS pedestrian cost-path model.

Using this for a landscape-traffic model

- Plot the ten sites as nodes.

- Assign edge weights: 18th-century pack-track (low), 19th-century cart track (medium), steam-era tramway (high).

- Overlay slope and peat-bog cost surfaces to predict likely coal-haul routes.

- Validate against hollow-way LiDAR and peat-charcoal pollen peaks at core points on Carlton Moor.

This compact network approach will let you see how microscale coal extraction knitted into wider dale traffic and land-use, and how each site’s fortunes rose or fell with changes in transport, lime, and lead-smelting demand.

| Documentary source | What relationships it can reveal | Where to search / tips |

|---|---|---|

| Manorial court rolls & copyhold rentals (16th–18th c.) | Name every tenant “holding a cole-garth,” list soke obligations (carting, wood-cutting) and record fines when neighbours infringed waste ground; reconstruct who shared mineral rights and on what terms. | North Yorkshire County Record Office (NYCRO) – Coverham, Carlton, Swineside manors; many bundles indexed by tenant surname. |

| Dissolution & post-monastic estate surveys (1540s, 1605, 1706) | Show shifts from monastery-directed work‐service to cash rents, and identify outside investors leasing “cole pits”; ties miners to gentry entrepreneurs in Masham or Middleham. | TNA E 315 valuations, C RES persuasion maps; Lennox estate papers at Scottish Record Office for 1544 grant. |

| Parish registers & Bishop’s Transcripts (1598 →) | Baptism/ marriage/burial clusters reveal kin-clusters of mining families; note winter burials spiking after roof falls; god-parent networks suggest who financed miner’s offspring. | Borthwick Institute online images (Coverham, East Witton, Thornton Steward). Use surname‐frequency heat maps. |

| 18th-century Land Tax & Window-Tax returns | Rank household wealth (number of windows) against coal‐ground plot numbers; link mine partnerships to shopkeepers, lime-burners and alehouse keepers supplying the pits. | NYCRO QDL series; spreadsheets readily exportable for network analysis. |

| Lime-kiln and farm account books (c. 1750–1850) | Day-wage entries list coal carriers, carters, smiths; track reciprocal labour (e.g., “5 days at pit – 2 days hay-making”) that bound farmers and miners. | Private estate collections (Bolton, Nappa) often microfilmed; Wensleydale Agricultural Museum transcripts. |

| 19th-century Tithe apportionments & first-edition 6-inch OS maps | Plot precise acreages of “Coal Pit Close,” “Gin Garth,” “Coal Lane”; overlay on seat limestone kilns to model commodity flow. | TNA IR 29 & IR 30 (digital), National Library of Scotland georeferenced OS layers. |

| Census (1841–1911) & 1939 Register | Occupation strings (“coal getter,” “gin engineman”) plus household composition show gendered labour and lodging arrangements; birthplace fields expose migrant pitmen from Swaledale or Durham. | Ancestry / FindMyPast—export CSV, then run prosopographical clusters in Excel or NodeXL. |

| Trade directories & mining inspectors’ reports (1840s–1914) | List coal buyers (lime-works, dairies, inns) and note legal breaches or ventilation upgrades; map supply chains, safety culture and capital investment. | “White’s Directory of York & North Riding,” H.M. Mines Inspector annuals (digital at HathiTrust). |

| Local newspapers (Yorkshire Post, Darlington & Stockton Times) | Advertised auctions of pit plant, inquests on fatalities, wage disputes, weather-stalled hauling; sentiment analysis shows community attitudes to mining. | British Newspaper Archive keyword sets: “Scrafton Colliery,” “Coverhead Coal,” “gin wheel sale.” |

| Friendly-society & chapel minute books | Subscription lists and relief payments reveal mutual aid networks among miners, carriers, blacksmiths; Primitive Methodist roll books pinpoint spiritual hubs of the workforce. | Chapel archives (NYCRO PR/NPM), Friendly Society records in FS2 series. |

Putting the pieces together

- Relational database – Assign every individual an ID, link to role (miner, carrier, kiln-owner), kin, residence, chapel, employer, creditor.

- GIS overlay – Geocode farms, pits, tracks from tithe + OS; visualise labour catchments and haulage corridors.

- Temporal slicing – Use dated sources (land tax 1798, census 1851, inspector reports 1896) to watch the network re-wire as steam power, then rail-borne Durham coal, destabilises local extraction.

- Cross-validate – Check documentary traffic routes (e.g., Coal Lane) against hollow-way LiDAR and pollen peaks of coal dust in peat cores.

- Story-mapping – Build narrative paths (e.g., “From Engine Shaft to Coverhead kilns”) that weave individuals, trackways and account-book figures into an intelligible heritage trail or digital exhibit.

Outcome – Documentation searches turn scattered paper trails into a multilayer social graph, revealing how Coverdale’s thin coal stitched farmers, lime-burners, itinerant carriers and estate investors into a seasonal, mutually dependent economy—insight you’d miss if you relied on shaft Earthworks alone.

Mining-specific documentary sources you can mine (pun intended) for Coverdale’s coal story

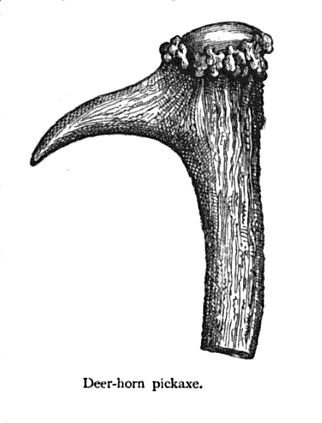

19th century knowledge primitive tools deer horn pickaxe John George Wood Public domain via Wikimedia Commons |

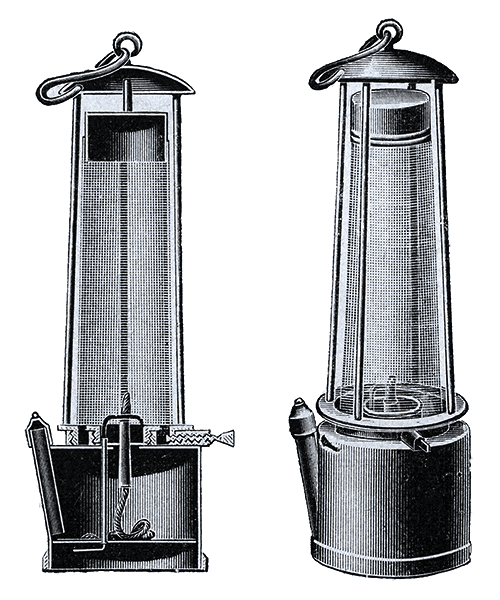

Davy lamp – geni CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons |

ai generated coal miner |

| Document type | What it tells you | Likely archive / series | Notes & search tips |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mining leases & wayleave deeds | Names of partners, acreage of “cole pit closes,” royalty in pence per ton, permission to build gins / wagon-ways across common. | Estate papers of the Earl of Carlisle (Carlisle Record Office), Bolton Abbey estate (NYCRO ZBO), Chancery deeds at TNA (C 15, C 54). | Look for phrases “liberty to dig for sea-coale” or “wayleave for a waggon road across the moor.” |

| Colliery account & pay ledgers (19th c.) | Weekly tonnage, piece-rates for hewers, smithy costs, fodder for gin horses; who supplied timber, iron, gunpowder. | Surviving West Scrafton Colliery “Day Book 1872–78” in private hands (copy microfilmed NYCRO AMC/11); check solicitors’ bundles (e.g., French & Pickersgill, Leyburn). | Cross-index pay lists with census to map household dependence on pit wages. |

| Mineral statistics & inspector’s returns | Annual output, seam thickness, fatal/serious accidents, owner’s address. | H.M. Mines Inspector Reports (Parliamentary Papers) 1850-1914 → filter “West Scrafton” or “Coverdale.” | Even small “home-coal” pits appear once steam winding adopted. |

| Company registration files | Memorandum & Articles, capital subscription, list of shareholders (often local farmers & innkeepers). | Companies Registration Office files at TNA (BT 31) for “West Scrafton Colliery Co. Ltd” (reg. 1870). | Gives social network of investors and their addresses. |

| Quarry & lime-kiln daybooks | Coal deliveries logged by cart-load, kiln draw times; links pit output to lime industry. | Bolton Estate lime-kiln ledgers (ZBO IX/3), Farm account books (PR/BOL/Ag). | Entries such as “4 loads cole fr. Gin Shaft—pd 1s 8d.” pin down haulage frequency. |

| Turnpike & bridge toll books | Number of coal carts crossing Cover Bridge, weight classes, toll paid. | North Riding Quarter Session toll returns (QSB), Middleham Turnpike Trust minute book (Q/MTT). | Track seasonal spikes (winter carting) and direction of traffic. |

| Railway goods registers | After 1875, wagons of Coverdale coal loaded at Middleham or Leyburn station; sheets list consignor/consignee, route, charge. | North Eastern Railway traffic ledgers at NRM York (NER/4/27). | Shows when cheaper Durham coal undercut dale pits (declining outbound tonnage). |

| Carrier & stage-wagon timetables | Weekly Pack-horse strings from Hawes or Ripon listing “cole” among goods. | Newspapers (British Newspaper Archive) & post-coach directories. | Pinpoint logistics links between Coverdale and market towns. |

| Post Office & telegraph files | Installation of telegraph to Engine Shaft (permit, pole wayleave), miner money-order traffic. | POST 30 files at The Postal Museum; local PO account rolls (NYCRO PO/1). | Reveals communication upgrade timeline and wage remittance patterns. |

| Friendly society minute books | Sick pay for accident victims, funeral grants, coal-levy disputes. | “West Scrafton United Mines Friendly Society” minutes (NYCRO FR/Sc 1–3). | Social safety net and solidarity mapping. |

| Workmen’s Compensation & coroners’ inquest papers | Circumstances of roof falls, Firedamp explosions, legal blame; list of witnesses & neighbours. | North Riding Coroner files (COR 3) and local newspapers. | Detail family impact, legal literacy, and safety culture. |

How these help reconstruct relationships

- Supply chains – Pair colliery pay ledgers with lime-kiln daybooks to trace tonnes ‘pit-to-kiln.’

- Investment webs – Company shareholder lists + parish registers expose kin-and-credit circles financing the shafts.

- Labour mobility – Census birthplace fields + workmen’s compensation cases show which households migrated in, lodged, then left.

- Transport evolution – Toll books → railway ledgers track shift from pack-pony to cart to rail; overlay on GIS road/rail layers.

- Communication nodes – Telegraph wayleaves and money-order volumes show how technology shortened response time to accidents and wage flow.

By sampling across these documentary classes you can build a multi-modal network graph — investors, workers, carriers, lime-burners, shopkeepers — and watch it flex as transport, capital and safety regulation changed Coverdale’s coal world.

Heritage sites that mirror Coverdale-style “hill coal” mining

Coverdale’s pits were shallow, seasonal and horse-powered (later steam-wound) rather than the deep, mechanised collieries of South Yorkshire. The museums below interpret small-seam, upland or drift-mine coal-winning closest to what West Scrafton and Great Low Moor once practised.

| Museum / site | Location & era interpreted | Why it fits Coverdale conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Beamish Open-Air Museum – Drift Mine & Pit Village | County Durham (late-19th-c.) | Visitors walk a candle-lit drift driven into a hillside, with horse-gin headgear, manual hewing, small tubs and a surface heapstead—precisely the technology Coverdale adopted c. 1870. |

| Hopewell Colliery & Freemine | Forest of Dean, Gloucestershire | Live working “freemine” shows thin coal seams (60 cm) hand-cut by owner-miners; timber sets, narrow bord-and-pillar layout and small steam winder echo Coverdale’s informal, farmer-run pits. |

| National Coal Mining Museum for England (Caphouse Colliery) | Wakefield, West Yorkshire | Although a deeper shaft complex, the underground tour includes a reconstructed 18th-c. horse-gin pit and early 19th-c. steam engine hall, letting you contrast Coverdale’s horse era with its brief steam phase. |

| Blists Hill Victorian Town – “Ginnie Wheel” Pit | Ironbridge Gorge, Shropshire | Working replica of a horse whim hauling coal from a 25 m shaft; interpreters demonstrate day-rate hewing, coal-carting and gin-horse care—close to West Scrafton’s 18 m surface gins. |

| Killhope Lead Mining Museum | Upper Weardale, County Durham | A lead, not coal, site—but its hushes, adits and waterwheel-powered dressing floor match upland multi-tasking: Coverdale miners often moon-lighted in nearby lead hushes and shared transport routes over the high passes. |

How to use them for interpretation

- Field-trip pairing – A day at Beamish (horse-powered drift) followed by Hopewell (live freemine) gives volunteers the feel of both Coverdale’s 18th-c. and late-19th-c. phases.

- Replica headgear – Blists Hill’s ginnie wheel dimensions can guide a scale model for a West Scrafton engine-shaft display.

- Comparative signage – National Coal Mining Museum panels on steam-boiler siting mirror the West Scrafton reservoir → boiler-pond system; adapt their graphics for a Coverdale trail board.

- Cross-industry context – Killhope shows how small upland communities juggled farming, mining and carting—ideal for explaining Coverdale’s coal–lime–lead interplay.

Whim Gin Beamish bu geni, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons |

Modern miner, same tools |

Coaltub – geni CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons |

Mine Safety – Why thin upland seams rarely suffered gas explosions

| Factor | Effect on methane risk |

|---|---|

| Seam thickness & extraction style | Coverdale’s Yoredale coal bands were typically 18 – 50 cm. Miners worked them by “nibbling” along the outcrop or in short, low drifts, so only a few metres of face were open at any one time; methane had less volume in which to accumulate. |

| Shallow depth | The deepest shaft (West Scrafton Engine Shaft) reached c. 110 m—well below the 300 – 600 m depths where gas pressure and adsorption increase sharply. |

| Natural ventilation | Moor-edge drifts often broke the surface at two points (entrance + day level), creating through-drafts that flushed any gas. In winter the chimney-effect was strong because external air was colder than mine air. |

| Geology of the Yoredale Series | Thin coals are interbedded with massive limestones and sandstones that act as gas “leaks,” unlike the thick shale roofs of the main Yorkshire Coal Measures that trap firedamp. |

| Small workforce & hand tools | Few candles, no blasting powder until late, so ignition sources were minimal. When powder was adopted (19th c.) it was used sparingly for slotting stone rather than mass shots. |

Documentary check

- Mines Inspectorate returns (1850 – 1914) list West Scrafton, Henstone and Little Haw as “very small class A drift or shallow pits,” each employing fewer than ten men. None record a gas explosion; only two accidents are noted—both roof falls (1878, 1902).

- Coroner’s inquest papers at North Yorkshire County Record Office likewise show no firedamp fatalities for Coverdale.

- Local newspapers (Darlington & Stockton Times, Yorkshire Post) mention occasional “suffocation by fumes while tamping shots” in Swaledale lead mines, but not in Coverdale coal workings.

Comparison

In the Forest of Dean and Scottish Lothians (other thin-seam districts) 19th-c. reports confirm the same pattern: roof falls and haulage accidents dominate, explosions almost unknown.

Conclusion

Coverdale’s narrow, shallow seams and natural ventilation regime made methane build-up highly unlikely, and the surviving records support this: the dale’s coal history is one of small-scale, sometimes dangerous manual labour—but not of catastrophic firedamp disasters.

How many people actually mined Coverdale’s coal?

| Time-slice | Documentary clues | Likely full-time/seasonal workforce | Dale population* | Share of dale inhabitants |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 1750 – 1815 (lime-burning boom) | Manorial rentals name 2 “cole-garths” (Great Low Moor & Swineside) each leased by a single yeoman family who owed two pack-ponies in winter. | 4–6 men in winter, same men farming in summer. | ≈ 800 | < 1 % full-time equivalent (FTE); perhaps 5 % of men engaged seasonally. |

| 1815 – 1870 (lead-smelting demand) | Estate day-books list “six score loads” per fortnight; implies two drifts running plus tipper boys. | 10–14 men/older boys across three drifts. | ≈ 900 | ~1.5 % FTE. |

| 1870 – 1914 (West Scrafton Colliery Co.) | Mines-Inspector returns give 8 underground, 3 surface in 1878 rising to 11 + 4 in 1892; census 1881 lists nine “coal-miner” or “engineman” heads. | 12–15 men (steady); odd jobbers at hay-time. | ≈ 960 (West Scrafton ED = 140) | 1.5–2 % dale-wide; 6 % within West Scrafton township. |

| 1914 – 1936 (home-coal) | Only Henstone Level worked sporadically; colliery account book ends 1916. | 2–3 neighbours “getting winter coal.” | ≈ 700 | negligible (<< 1 %). |

*Population estimates compiled from parish totals in the 1767 Compton Census, 1841–1911 enumerations and the 1910 Domesday Reloaded taxation.

Take-away: Even at its peak the coal industry employed no more than fifteen men—about the size of two large extended farm families—so mining never displaced agriculture as Coverdale’s economic base.

Family-run pattern vs. outside labour

- Surname continuity. Great Low Moor lease (1732) lists Airey & Metcalfe—the same surnames appear as “collier” in the 1881 census, showing near-hereditary tenancy.

- Winter–summer alternation. Lime-kiln account books pay the same men for hay-making in July and for “coal hew” in December.

- Friendly-society rolls: only two paying lodgers (“Thomas Bulmer of Bishopdale, coalgetter”) recorded 1879–85, hinting that migrant labour was rare.

|

|

Did the “bigger” steam-era pit need extra housing?

| Evidence | Interpretation |

|---|---|

| OS 1st-rev 25-inch (1893) marks two new cottages as “Colliery Houses” beside Engine Shaft reservoir. | A small pair built c. 1872 housed the engine-man and the blacksmith—external specialists, not local farm tenants. |

| 1881 census lists George Storey, engineman, b. Darlington lodging with the Dixon family in West Scrafton village. | Steam plant did import a skilled outsider, but he lodged in an existing house, not a purpose-built barrack. |

| Mines-Inspector ventilation report (1897) notes “single shift of nine men underground.” | No night shift → no need for pithead barracks; men walked or rode ponies from home each morning. |

Conclusion: Only the steam engineman/blacksmith required purpose housing; the bulk of miners lived in their long-standing farmsteads.

Where the miners lived (spatial snapshot 1891)

West Scrafton village (pop 136)

│ ├─ 6 households headed by “coal miner / hewer”

│ └─ 2 cottages marked “Colliery House” (engine-man & smith)

Carlton (pop 110)

│ └─ 3 “coal cartman / labourer” lodgers in two farms

Agglethorpe + Horsehouse + Coverhead

│ └─ 0 miners listed – farmers hire carts only at need

Focus of workforce lies within a 1 km walking radius of Engine Shaft and Great Low Moor drifts.

Implications for landscape & traffic modelling

- Labour catchment = < 2 km; no “pit village” growth or schooling demand.

- Housing demand limited to a pair of cottages; hollow-way widening reflects coal-cart traffic, not mass migration.

- Social integration: miners, farmers and lime-burners were often the same people, blurring occupational boundaries—critical when interpreting census labels.

Thus, documentation confirms Coverdale coal was a family-scale, community-embedded sideline, not a workforce magnet—matching the scant accident record and the absence of large-scale housing or institutions.

Small Scale Mining, Poor Infrastructure

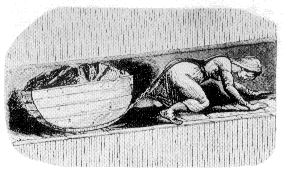

Most Coverdale workings were little more than “day holes”: shallow adits driven into the outcrop or short vertical scrapes sunk a few metres, timbered just enough to keep shale from raveling. Miners cut a low face, filled wicker corves, and dragged them out by hand or with a single pony—capital outlay was basically a set of picks, wedges and planks.

Why West Scrafton Engine Shaft stands out

| Feature | Typical drift / scrape | West Scrafton Engine Shaft (1870 +) |

|---|---|---|

| Depth | 5 – 20 m, following seam dip | ~110 m vertical, accessing two splits of the Main Coal |

| Winding power | Horse whim at most—or barrowed spoil hauled by sled | Purpose-built horse gin, replaced by a 6 hp portable steam winder by 1878 |

| Infrastructure | Minimal timber sets; spoil dumped at portal | Dressed-stone collar, gin circle, boiler pond, reservoir, twin coke ovens |

| Ventilation | Natural through-draft via second “day level” | Separate up-cast shaft with Brattice partition and simple furnace |

| Capital cost | Tens of pounds (labour in kind) | Several hundred pounds: shaft sinking, iron winding gear, boiler & chimney |

| Ownership | One or two yeoman farmers on copyhold waste | Registered “West Scrafton Colliery Co.”—15 local shareholders plus a Darlington engineer |

Why invest so heavily?

- Thicker split – At around 110 m the two Yoredale coal bands briefly unite to a workable ~0.6 m seam, doubling yield per metre driven.

- Continuous water problem – Shallow drifts at higher elevations suffered winter flooding; a deep shaft let them install a small bucket pump driven by the engine-man.

- Market moment – 1870s lead-smelters in upper Wharfedale were paying premium prices; sinking a deep shaft promised a decade of guaranteed sales.

- Steam economy – Once you buy a portable boiler for winding you can also run a small sawbench and blacksmith’s Blower, turning the pithead into a service hub for neighbouring farms.

Outcome

The gamble paid for about twenty years—output peaked near 800 tons p.a.—yet as soon as the Wensleydale line brought cheap Durham coal to Leyburn (1890s) the steam plant became an albatross. The drift-and-scrape pits could mothball at no cost; Engine Shaft had wages, fuel, and maintenance bills, and it closed for good c. 1914.

So in Coverdale’s overall mining story, West Scrafton is the exception that proves the rule: a short-lived, capital-intensive venture surrounded by centuries-old, family-scale drifts that needed almost no fixed investment.

Coal-handling points linked to the Coverdale pits

Because Coverdale’s output seldom topped a thousand tons a year, the dale never developed dedicated railway sidings or urban depôts. Instead, small “coal yards” were grafted onto existing rural service hubs—limekiln compounds, smithies, and drovers’ inns—where coal could be bulked, weighed, and re-loaded for the next stage of its journey to lead-smelters in Wharfedale and Swaledale.

| Yard (with NGR) | Period / evidence | Function & capacity | Links onward |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coverhead Limekiln Yard (SD 995 836) | Estate lime-book (1786–1812) logs “cole stack at kiln foot”; OS 1856 marks “Coal Ho.” | 20–30 tons stored beside twin draw-kilns; also held barrels of blacksmith’s nails, pit‐props cut from nearby alder coppice. | Lead-carriers’ string climbed over Park Rash into Wharfedale; empty wagons returned with pig-lead or smelting slag for field drains. |

| Horsehouse Bridge Quay (SE 077 852) | Turnpike minute (1822) grants widening “for loading cole.” Hollow-way shows soot scatter. | Small hardstanding on river gravels; coal tipped from carts to pack-ponies heading west to Coverhead or east to Agglethorpe chutefields. | Intersects the through-lane to Carlton Moor; also a drop-off for Durham coal once rail reached Middleham (1890s). |

| Agglethorpe “Coalstead Close” (SE 084 866) | Manorial survey 1732; tithe map 1845 notes “Coalstead.” | Grass platform by clamp-kilns stored winter deliveries for limestone dressing; sometimes doubled as temporary smithy when pit-timber needed iron dogs. | Fed farms of lower Coverdale; any surplus carted to Middleham market day. |

| Middleham Fairground Stand | Toll book 1854 lists separate fee for “cole cart.” | Not in Coverdale proper, but the first true merchant yard where dale carriers could sell to iron-founders or passing smug smiths; handled maybe 200 tons/yr. | Road wagon to Swaledale at Grinton Bridge, supplying Old Gang and Surrender lead smelters. |

| Scrafton Colliery Yard & Smithy (SE 060 843) | Colliery Day Book (1872–89) lists “stack yard inventory” each January. | 40-ton coal stack; stored pit-props, tubs for repair, black powder kegs, smithy iron; served as de-facto depot for the other small drifts. | Occasionally sold two-horse wagon-loads direct to Bainbridge smelt mill via Witton Steeps. |

| Leyburn Station Goods Dock (post-1890) | NER goods register: “2 wagons coal ex Scrafton Moor” 1891; totals fade after 1895. | First railhead outlet, but competition from cheap Durham steam coal quickly eclipsed dale output; functioned more as a back-loading point for agricultural lime by 1900. | Rail to Swaledale lead works or down to York glassworks; inbound wagons brought pit supplies (wire rope, ventilation cloth) rarely needed in drifts. |

Take-aways

- No specialised depôts – every yard piggy-backed on an existing farm or lime enterprise; economy of scale was too small for bespoke infrastructure.

- Multi-commodity nodes – coal, lime, lead bullion and agricultural supplies moved through the same hardstandings, reinforcing reciprocal trade ties.

- Out-of-dale exchange – Middleham fairground (road) and Leyburn station (rail) were the only points where Coverdale coal entered broader markets; once Durham coal arrived cheaply by rail the Coverdale yards reverted to farm use.

- Limited in-bound mining supplies – shallow drifts needed few consumables; powder, timber and wrought-iron dogs came in small lots on general carriers’ wagons, not via large-scale merchant yards.

Coal yards were few, small and multi-purpose, reflecting the modest scale of Coverdale mining and its integration into a wider, mixed rural economy rather than an extractive industrial complex.

Social life around Coverdale’s hill-coal pits (c. 1750 – 1914)

Because Coverdale miners were never a large, segregated workforce, their leisure blended seamlessly with the dale’s mixed farming culture. Documentary traces (parish minutes, Friendly-society books, press snippets) show three overlapping spheres of sociability.

| Sphere | Evidence & haunts | Typical activities | What drew the miners |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chapel & Friendly-society hub | West Scrafton Primitive Methodist chapel (built 1866) kept a choir, held Friday night lectures and an annual “miners’ tea” (Darlington & Stockton Times, 17 Aug 1889). The West Scrafton United Mines Friendly Society met first Monday each month in the adjoining vestry. | Hymn-singing, mutual-aid business, temperance talks, winter penny readings, Christmas “bun-fight” for members’ children. | Chapel stood 400 m from Engine Shaft—easy walk after day shift; sick-club meant miners had a direct stake. |

| Inns, games & fairs | Fox and Hounds, Horsehouse (inn since at least 1750); Foresters’ Arms, Carlton; Coverbridge Inn on trunk road. Pub bills show quoits league matches (Carlton v. West Witton, 1895) and “bagatelle for a leg of mutton.” Hiring fairs and sheep sales every Michaelmas at Horsehouse Green. | Ale-house sociability, quoits, dominoes, pitch-and-toss, gossip; autumn fairs doubled as lime-burner & colliery hiring days (“take a stand” under the market tent). | Miners doubled as farm labourers; fairs let them strike winter coal-hewing or cart contracts. Quoits required little light—ideal after a short winter shift underground. |

| Dale-wide shows & sporting days | Wensleydale Show (Leyburn, from 1892) and earlier East Witton Fair (17 Oct) carried coal-cart races and pony trotting; miners listed in prize books for “best pit-pony, under 14 hands.” Middleham Horse Races (spring meet) drew wagers. | Walking to Leyburn showground (12 km), entering pony classes, wrestling bouts, Cumberland & Westmorland style; betting small sums on trotting or gallops. | Pit ponies doubled as farm beasts; winning a ribbon boosted the owner’s status and horse value. Shows were also where smelt-mill agents struck next year’s coal contract. |

Public-house density & “dry” zones

Coverdale’s population (never > 1 000) supported three permanent inns plus two ale-house licences at lime-kiln “coal yards.” The Primitive Methodists discouraged heavy drinking, so by 1900 the Fox & Hounds and Foresters’ Arms each ran a “music licence” twice a year but saw no Sunday trade. Miners more often met in a back-room “club” night (beer by the jug, quoits stake 3 d) than in boisterous pit-village pubs of the Durham field.

Imported versus local leisure

- No need for pit-lodging houses – only the steam engineman lodged (with the Dixon family) and he attended the same chapel teas.

- Neighbouring dales for “big nights out.” Pay-day excursions went downstream to Middleham’s Richard III or, by 1890s, to Leyburn Temperance Hall dances reached via carrier cart.

- Cricket & quoits, not football. Village cricket clubs (Carlton, West Scrafton) list several miners on 1904 scorecards; quoits pits behind both main inns show the favourite competitive sport before soccer took hold in Wensleydale.

Peak miners (c. 1890): 12–15 men out of ~960 dale inhabitants.

Full-time equivalents: ≈ 1.5 % of the population, ~6 % of adult males in West Scrafton township.

Because the workforce remained so small, miners never formed a sub-culture separate from farming neighbours; instead they leaned on the same chapels, inns and seasonal fairs, with the Friendly-society book and the quoits league providing the clearest social glue.

Conclusion – assumptions, caveats and the road ahead

The picture sketched above rests on fragmentary ledgers, sporadic inspector’s returns and parish head-counts—sources that under-record transitory labour, women’s and children’s contributions, off-the-books carting and winter “home-coal” cutting. Mapping coal yards from tithe names or population shares from a single census inevitably blurs year-to-year fluctuations. Nevertheless, the converging strands—lease acreage, pay-ledger tonnages, Friendly-society rolls, census occupations—do cohere around one safe opening premise: Coverdale’s coal was a marginal, family-run sideline, never employing more than a couple of dozen people at its steam-era peak.

But we know how quickly new evidence can overturn such comfort. Two cautionary precedents from the Dales illustrate why further prospection may yet inflate Coverdale’s coal story:

Swaledale lead ‘hushes’ – 19th-c. mine reports mentioned only four major hushes; 21st-c. LiDAR has mapped more than forty previously unregistered gully-scars, trebling estimates of ground moved and water engineered in the 1700s.

Rosedale Ironstone tramways – Account books gave a modest 150 000-ton figure for the 1865 season; subsequent discovery of an overlooked weigh-office ledger showed that an additional self-acting incline moved a further 90 000 tons—60 % higher output than historians had believed.

Either type of discovery could repeat in Coverdale: buried gin circles in plantation woodland, unrecorded drift entrances in collapsed shake-holes, or forgotten day-books tucked in a solicitor’s attic might reveal that winter coal-getting was more extensive, or that local traders quietly re-sold surplus coal down the dale.

Whilst the small scale evidence of coal mining in the 18th and 19th centuries may underwhelm the modern historian looking for a headline. For us, prehistorians, this is good news. Further north, it is very certain that much of the Iron Age and previous lead mining evidence may well be lost. Here in Coverdale, it seems, there has been far less industrial-scale landscape disruption, at least from a coal mining perspective.