Contents

- 1 Roman Rig

- 2 What the antiquarians thought

- 3 Lack of Dating Evidence

- 4 Assessment

- 5 Reassessment, 2025

- 6 Early Field Surveys & Antiquarian Notes

- 7 Mid-Late 20th-Century Rescue Excavations

- 8 21st-Century Professional Surveys

- 9 Current Understanding of the Complex

- 10 Comparison with Roman sites to the south

- 11 Marching Camps near the Rig

- 12 Frontier Forts Immediately South of the Rig

- 13 Implications for the Rig as a Frontier

- 14 Summary Conclusion

Roman Rig

The Roman Rig is a defensive dyke built to defend against attack from the south. It runs from Sheffield, past Templeborough and carries on almost to Doncaster. If this is a Brigantian dyke it would certainly add weight to Websters definition of the Roman border in the period.

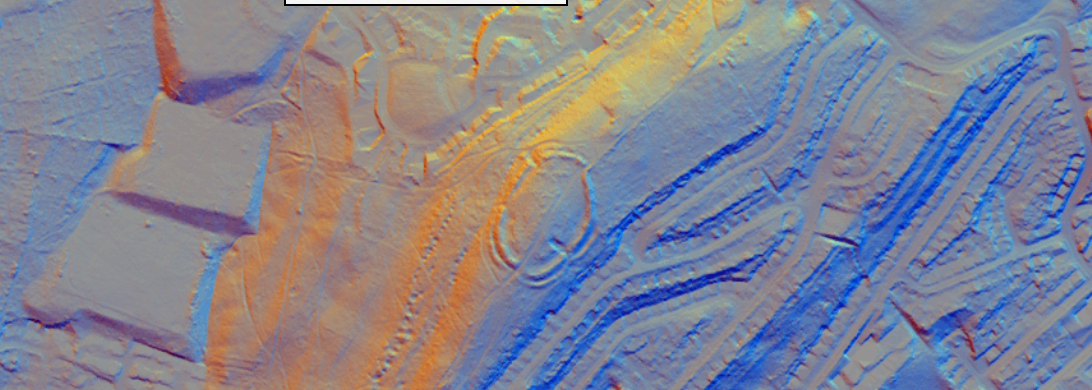

Diagram of Roman Rig (based on Boldrini and Bailey)

Picture by https://www.gleaden.plus.com

The case for the Roman Rig in Sheffield being of a 1st c AD construction, whilst still not proven, grows increasingly stronger, as was highlighted recently by Nick Boldrini in his reassessment of the Rig. In fact for over a hundred years, antiquaries have been linking the existence of Roman Rig to the local archaeology and concluding they were part of a Brigantian defence against Rome. In fact if these were built by Venutius, the lack of dating evidence would be expected, given the potentially short active life of these Earthworks.

Picture by https://www.gleaden.plus.com

The case for the Roman Rig in Sheffield being of a 1st c AD construction, whilst still not proven, grows increasingly stronger, as was highlighted recently by Nick Boldrini in his reassessment of the Rig. In fact for over a hundred years, antiquaries have been linking the existence of Roman Rig to the local archaeology and concluding they were part of a Brigantian defence against Rome. In fact if these were built by Venutius, the lack of dating evidence would be expected, given the potentially short active life of these Earthworks.

Pictures by https://www.gleaden.plus.com

Pictures by https://www.gleaden.plus.com

What the antiquarians thought

Many antiquarians were attracted to the Roman Rig, many thought it was a Roman Road, however others of more insight interpreted it as a defensive system and linked it to the Iron Age hill forts and camps which appear on it's northern side. Some of the more famous antiquarians to comment of Roman Rig included Mrs. Ella S. Armitage, Mr. John Danial Leader, Mr. John Guest, Mr Sidney Oldall Addy, Mr. Joseph Hunter and Mr. Elijah Howarth:

"on the north side of the river, over against Templeborough, is a high hill, called Wincobank, from which a large bank is continued without interruption almost five almost five miles, being in one place called Danes bank. And about a quarter of a mile south from Kempbank (over which this bank runs) there is another Agger, which runs parallel with that from a place called Birchwood, running towards Mexborough, and terminating within half a mile of its west end; as Kempback runs by Swinton to Mexborough moor" - Gibson (Camden's editor) 1695.

"Mr Leader tells us of a time when this Earthwork was seen on the northern bank of the River Don, in Sheffield, near to the Wicker, in the region known as the Nursery, and so not far from the place where, much later than the date of the earthwork, was built the Lady's Bridge, which probably had superseded a ford, with perhaps a line of leppings. At Neepsend, the Don was crossed by Leppings until the year 1795.

From the Done, the rampart followed a course where there was afterwards a footpath, but that track became Occupation Road, known now as Grimesthorpe Road; and here Mrs Armitage becomes our guide, telling us that if we had to proceed to the Upper Grimesthorpe Road in her time, then, near to the point where the Osgathorpe Road turns out of the Grimesthorpe Road we should have seen the first traces of this dyke. Here it was "gnawed away to its original course of stones, and very little of that; but follow it to the point where it descends the hill into the Grimesthorpe valley, making a sharp turn to the left, and it will be found as perfect as anywhere on its course.

"On the opposite side of the valley it has been entirely cut off by a quarry; but reappears at a point which shows that without climbing to the camp which crowns the Wincobank Hill, it ran like a terrace along the side of the hill, and followed the line of a remarkable fault or upheaval of the sandstone strata, till it crossed the Blackburn valley, where the Yorkshire Engine Works have destroyed all trace of it. But cross the valley and it will be found again near Meadow Hall, first on the right, then on the left hand side of the road."

Hunter, in his "South Yorkshire," does not seem to have examined the earthwork between Wincobank Hill and Sheffield. He says that "The earthwork at Wincobank is amongst the wood, and is not to be discovered without a strict search. The carriage road from Brightside to Wincobank village passes at a distance of about three hundred yards on the east. It cuts the Roman Rig, which appears on the right, raised high above the heads of the passengers. This is near the summit of the hill. It points directly to the work. Here it appears with a wide huge back, deep sloping banks, to a base which can hardly be less than one hundred and twenty feet. The slope towards the north is the longest.

A footpath is carried along the top. Pursuing this path for about three hundred yards we enter a wood. The ridge may be traced through the wood, but is lost in the meadows between the wood and Blackburn Brook. It has evidently disappeared from the labours of agriculture. We recover it again at Meadow Hall. Mr Fletchers barn stands on it. It is here on as wide a base as at Wincobank, but the elevation is not so great. In a field which is separated from the Meadow Hall homestead only by a lane, it is perfectly visible; and here, looking back, we have a fine command of the whole line from Wincobank.

It accompanies the horse road from Meadow Hall to Hill-top, keeping a little to the left of it, and it is here and there yearly warn down by the plough. It appears evidently a little to the south of Hill-top village, crossing the road called Sopewell Lane, which connects that hamlet to Kimberworth. Here it is not called the Roman Rig, but Scotland balk, and the reason which is given for the name is, that it is a portion of a line which is drawn the whole length of the country to Scotland. Balk, it may be observed is a generic term for any lengthened line, as long as a piece of timber.

Near Sopewell lane it is very evident, but I was told not more than three years ago it was more distinct than now. It may be traced, pursuing a direct course, with few intermissions, for about a mile further, passing a little to the north of the village of Kimberworth, and crossing the road from Rotherham to Wortley near the second mile-stone. Three cottages, which cottages are known by the name of Barber Balk, stand upon it. Here it is very distinct indeed. A foot path runs along it, and it has been planted with a double row of oaks, Next it enters a plantation belonging to Lord Howard of Effingham, called Hudson Park. It's course between Hudson Park and Greaseborough is affected with some uncertainty; but probably the horse road by the little village of Whinfield may coincide with it.

At Whinfield I was told that thereabouts it became divided in two branches, one going to Greaseborough, the other in a more northerly direction, near a wall of Earl FitzWilliam's plantation, from thence to the fish ponds in the park, where about a hundred yards of it where said to be very distinctly to be seen, and thence by Hoober to Wath wood, Swinton, and Adwick."

He continues "At Greaseborough it is very distinct. It is there called the Balk. It Crosses the high road from Rotherham to Wentworth House. A foot path is carried along it to the head of the mill dam. It is lost for about three hundred yards, but appears again ascending the opposite hill to Nether Haugh, by the sides of Cross close and Lime Kiln Close. Between Nether Haugh and Upper Haugh it forms a wide road still in use today. The Methodist chapel, built in 1817, stands upon it.

At Upper Haugh it is lost, but a little portion of it is seen in a field about a quarter of a mile from the village, pursuing the same direction, and called the Roman Bank. It lies on the north-west side of a small natural valley, the other side being covered with wood. It comes to an abrupt termination in the middle of a large field, about half a mile south of Swinton pottery. It has evidently been dug away. It is still pointing towards Mexborough, but the indications of it beyond this point are, to say the least, very indistinct in that direction."

Hunter appears to have become confused as to the splitting of Roman Rig - "But in another line they are still evident. At Abdy, about a mile and a half from Upper Haugh, the ridge is as evident as at any other part of its course. But whether it connected with the line we have traced to Upper Haugh, or with the line which at Whinfield was said to have taken a more northerly course, is uncertain. One of the two, however, cannot be doubted, since the appearance and the construction of it are the same."

However, Mrs. Armitage is able to clarify the situation - "at a certain point in it's course, somewhere in what is now called Lady Rockinghams Wood, it sends out a branch, and henceforth runs towards Mexborough in a double line, sometimes as much as a mile apart. It's course is by no means straight, but sometimes turns sharply at right angles, as for example near the road by "Roman Terrace" near Mexborough. A very fine piece, showing well the ditch and counterscarps, may be seen in Wentworth Park, near the Greaseborough Entrance. At Mexborough the local name for it is the 'barmkin.'"

Hunters description continues - "It may be traced descending the hill leaving Abdy a little on the left, and descending the opposite hill to a wood. It crosses the road from Wath to Rotherham, at Shaywell close, where about fifty yards of it are entire. Between this place and Swinton it is scarcely to be seen; but from Swinton to the tunnel of the Dearne and Dove Canal it is very distinct. It lies over the tunnel, and may be seen on the Shrugs, where it presents the usual appearance, a bank covered with furze and broom. Here it divides Swinton and Adwick. It bends round to Mexborough, and is distinctly visible at a cottage belonging to Mr. Joseph Green, near Thief Lane. This is about half a mile from Mexborough, It can be traced no further."

Amongst the trees at Wilkinson Spring, Mr Addy examined the earthworks there, and he interpreted them as being part of the Roman Rig. These fragments, an embankment and a ditch, about 80 yards long he considered must have originally stretched from one end of the river Don, alongside the line of Grimesthorpe Road, running along the hill in a south-westerly direction; the other end of this fragment continuing in a north-easterly direction, across the brook at the bottom of the hill, where Grimesthorpe stands, so as to be continuous with The Ridgeway as it goes up the hill through the wood to Wincobank Camp, and so to Kimberworth and Greaseborough.

Addy also proposed that not only did the earthworks extend in the other direction, along or near the Grimesthorpe Road, by Meadow Head, Hall Carr and Burngrave to the River Don, but that there was a fortified line the other side of the River Don, carrying the defence through Upperthorpe, Steel Bank, Walkley and Stannington to the earthworks at Bradfield. His arguments were based chiefly on the local tradition and placenames.

Many antiquarians ventured to suggest that these earthworks were of Iron Age origin, many suggesting that they could be equated with a southern border of Brigantia, suggesting that they may have been built by Venutius as part of his preparations for the Roman advance. In the middle of the nineteenth century, Samuel Mitchel, a local antiquary suggested that the Roman Rig may have originally been part of an even larger defensive measure.

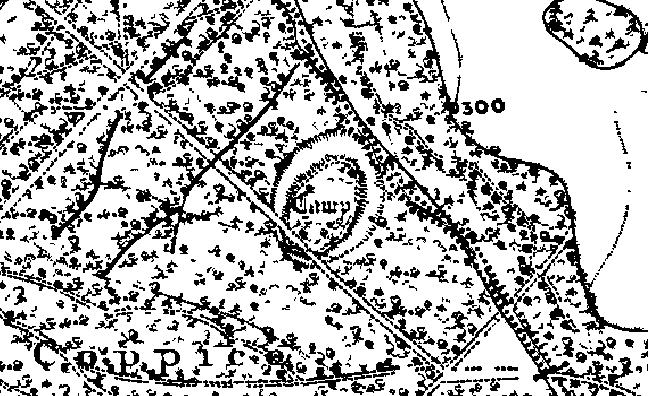

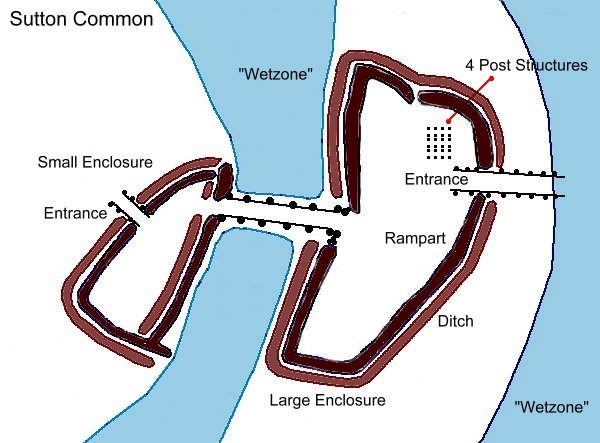

He suggested that an original fornication stretching from Combs Moss in Derbyshire (near Chapel-en-le-Frith) through Sheffield and Doncaster to Hatfield Chase may have existed. Beyond Hatfield Chase he argued, the ground was so boggy as to need no further defensive measure. He also suggested that the hill forts and enclosures of Mam Tor, Carl Wark, and Wincobank may have served as rallying points for people guarding the defences. To that list we can add the enclosures of Scholes Coppice, Hathersage and Great Roe Wood, others may have existed and the locations of Hoober and Mexborough seem likely candidates if we assume that such camps (if this defensive arrangement actually existed) were probably placed at equal distance along the line of the fortification. Added to these further possible indicators include Blacka Dyke, in south west Sheffield, and a place name in Sheffield called Castle Dykes, both of which are in broad alignment with the Doncaster-Sheffield arrangement, and a defence following these would work with Carl Wark. An outlier on the Doncaster side may have been Sutton Common.

The other plausible explanation offered for Roman Rig by antiquarians was that is was constructed after the collapse of Rome as part of the defences of the kingdom of Elmet, during the Saxon period.

There were also various attempts to link Roman Rig with a much wider seemingly defensive measures of a seemingly similar period the more popular notion was that Roman Rig and other measures created a defence from Manchester to Doncaster and beyond, this was related to a further line from Leeds to Aberford, created by the Aberford Dykes, and a further line ran from Richmond to Stanwick, thus enclosing, partially at least, the entire east and south borders of the Brigantian Pennine area. To this list we could also add the Cleave Dyke system, which would go some way to filling the gap between Aberford and Richmond.

Lack of Dating Evidence

"The dating of the ridge is very ambiguous, as none of the excavations have lead to any firm dating evidence. The only dateable evidence to emerge from the excavations was a rim fragment of a hammer head mortarium. type 3b' (Greene & Preston 1957. 27) which appeared in South Yorkshire circa A.D. 270. The sherd was found on top of the secondary filling of the ditch, suggesting the feature had fallen into disuse by the time the sherd was deposited, although how long after the construction of the ditch this was it is impossible to say. However this does not prove a pre-Roman or Romano-British date for the ditch as the sherd could have been incorporated into the ditch fill even if the ditch was constructed at a much later dale. Other dating evidence has been found; the antiquarian Addy (1893) mentions that the Blackburn coin hoard - a hoard of thirty coins dating to the first and second centuries AD found in 1891. had been found buried under a flat stone in the ditch of the ridge. However, the imprecise recording of these coins does not allow us to firmly date the ridge, although the find does strengthen the case for a Roman or Pre-Roman date.

Fleming (1973) also excavated a section through the ridge in 1973, and obtained two samples for radio carbon dating. Sample A was given a date of 1670 BP (circa A.D. 280). whilst sample B was dated to 4040 B-P- (circa 2090 B.C) (AERE nd). However, the excavation archive was poor and the context of the samples is unclear. Sample A appears to have come from the bottom fill of the ditch, but Sample B also appears to come from the ditch, giving us two widely different dates for the same feature. There appears to be no way to clarify this disparity, and it is probably best to ignore the dates due to the poor records associated with their location." Boldrini. 1999.

Assessment

In his recent assessment of the Roman Ridge - CREATING SPACE: A RE-EX AMINATION OF THE ROMAN RIDGE, Nick Boldrini sets out the most recent archaeological evidence for the date and reason for Roman Rig, although far from conclusive, Boldrini lays out a substantial case for a Brigantian origin for Roman Rig given the lack of clear evidence available so far; "On the balance of probabilities, my own view is that the ridge is probably from the period of Roman-Brigantian interaction, as there appears to be a clustering of evidence suggestive of this period."

The clustering of evidence Boldrini refers to, apart from the dating offered, is based on more general archaeological evidence as to the manner of construction, which indicated it was built quickly and went out of use soon after, and also with regard to its relationship with surrounding archaeology, the Iron Age sites have already been mentioned, but on top of these we must also add the Roman archaeology:

"Ryder however, who wrote an unpublished survey of the ridge in 1980. favoured the idea that the ridge was pre-Roman in date. 'This area of South Yorkshire was for some time a border area between the limit of the Roman advance, and the indigenous Brigantes to the north, who are thought to have been a confederation rather than a single tribe. When the Roman advance halted, the Brigantian Queen Cartimandua was on good terms with the Romans, probably as a form of client ruler.

This suited Roman policy, in that they had a secure border with a friendly neighbour, but this did not prevent them building what has been described as a cordon of garrisons (Hanson & Campbell 1986) along their borders to watch the Brigantes. and it is likely that the fort at Templeborough just south of the river Don (Fig 1), formed part of this cordon. However, in A.D. 68. according to Tacitus (1996). Cartimandua divorced her husband Venutius and married his armour bearer. This led to internal strife between Venutius who was also anti-Roman and Cartimandua, with Cartimandua being rescued by Roman Auxiliaries. This changed the situation, leaving a hostile neighbour on Rome's border and led to a series of campaigns by the then provincial governor, Q. Petilius Cerialis. and his successors, to pacify the Brigantes.

With this historical evidence, Ryder is tempted to see the Roman ridge as being built by the Brigantes as a border with the Romans or alternatively as some sort of defence against Roman attack. Whilst this would fit in nicely with the historical evidence, one must be wary of fitting archaeology to history, especially when dating of the archaeology is difficult. However, some archaeological evidence does lend credence to this theory. The crude construction of the bank without any form of revetting (Ashbee 1957) could be an indication that it was built fairly hurriedly, perhaps as a quick defensive earthwork by Venutius' followers.

Furthermore, the fact that the ridge appeared lo have had a short use span (Atkinson.1994) would fit in to the timescale of the Brigantian evidence, which spans just under three decades from contact to conquest... ...The proximity of Templebrough Roman fort, which has been dated in its first phase to 51-57 A.D. (May 1922). and the way the ridge could be interpreted as being built to face and dominate the fort, could be seen as suggesting that the construction of the ridge was a response to the setting up of this fort. If the ridge is interpreted in this way, this adds further weight to the possibility of a Brigantian date." Boldrini, 1999.

Research Notes"Though not yet dated by excavation, these earthworks are likely to be pre-Roman perhaps part of a defensive system dug by the Brigantes against enemies (Romans or other natives) advancing from the SE. They follow fairly low ground, never far from the river Don. They start about SK358880, run as a single earthwork NE through Grimesthorpe, E of Wincobank hill-fort to Hill Top (SH 397927). Here they fork, the W branch running .5 mile E of Scholes Wood hill-slope fort to Wentworth Park where it is well preserved, showing two banks and a medial ditch. It bends E at SK420985, can be found in the S part of Wath wood and E of the A633; it is visible across Bow Broom and ends W of Mexborough hospital. The E branch crosses Greasborough and runs through the E end of Wentworth Park where it is visible until Upper Haugh. It bends here towards Piccadilly where it disappears at SK 448981." Guide to Prehistoric England, Nicholas Thomas, 1960.

Reassessment, 2025

Roman Rig (often called the Roman Ridge, Barber Balk or Devil’s Bank) is a linear earthwork stretching some 27 km from Wincobank Hill, Sheffield, northeast towards Mexborough (grid SW 381 879 to SE 501 893) (en.wikipedia.org). Despite its Roman-era name, archaeological fieldwork over the past seven decades has revealed a much more complex, multiphase monument whose origins and function lie outside the classical road network.

Early Field Surveys & Antiquarian Notes

Preston (1950) carried out the first systematic field survey of the dyke’s visible earthworks between Sheffield and the Blackburn Valley, recording a single bank-and-ditch section on Wincobank Hill and noting its straight, non‐Roman alignment (academia.edu).

Ashbee (1957) and Greene & Preston (1957) published small-scale test-pits on the dyke near Wentworth and Kimberworth, finding merely subsoil and no road metalling, but confirming the bank-and-ditch profile typical of Iron-Age or early-medieval defences (academia.edu).

Mid-Late 20th-Century Rescue Excavations

Green (c. 1958) recorded photographs and section sketches during pipe-line works at Redhouse Farm, Adwick-le-Street, showing an Upcast bank of turf-reveted earth lies atop natural boulder clay—again without Roman road surfaces (heritagegateway.org.uk).

21st-Century Professional Surveys

Topographic Survey (ASWYAS 2009)

Mitchell Pollington’s detailed mapping of the surviving banks, ditches and occasional wooden revetments along the Doncaster stretch showed that sections survive up to 3 m wide, with the ditch usually on the upslope side—characteristic of defensive rather than transportation earthworks (archaeologydataservice.ac.uk).

Archaeological Evaluation (ASWYAS 2010)

Trial-trenches at key gaps and river crossings revealed only colluvial fills and occasional worked flints; no road metalling or gravel layers typical of Roman highways (heritagegateway.org.uk).

Watching Brief (Wessex Archaeology 2012) During cycle-path reconstruction, monitoring over exposed bank sections confirmed truncated ditch profiles but again found no Roman pavement (heritagegateway.org.uk).Current Understanding of the Complex

Taken together, the evidence paints a picture of a non‐Roman boundary work, likely constructed in the later first century AD by the local Brigantes Tribe as a defensive frontier against Roman incursions—or, by some scholars, in the post-Roman era (5th–7th c.) to defend the Kingdom of Elmet (en.wikipedia.org). Its key characteristics are:

Single or Double Bank-and-Ditch: Sections alternate between single-banked defences (e.g. Wincobank) and twin systems near Kimberworth, perhaps reflecting different construction phases or local responses to threat levels.

Strategic Alignment: It commands the Don valley approaches, seals off low-lying access points, and integrates with nearby Iron-Age forts (Wincobank, Scholes Coppice) and river crossings.

Material Culture: The absence of Roman road surfaces, yet the presence of occasional prehistoric flints in ditch fills, aligns the monument more closely with Iron-Age frontiers than military roads.

Later Reuse: In the Middle Ages, parts of the western dyke became parish boundaries (Ecclesfield–Sheffield), indicating its continued role as a territorial marker long after its defensive function had ceased (en.wikipedia.org).

In sum, Roman Rig is best understood today not as a transportation route but as a linear fortification and boundary—a Brigantian or post-Roman earthwork whose impressive scale and strategic siting dramatize the shifting patterns of control over South Yorkshire’s Don valley.

Templeborough Roman Granary remains at Clifton Park Museum - geograph.org.uk - 3406885" by Graham Hogg is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0" width="800" height="600" /> "Templeborough Roman Granary remains at Clifton Park Museum - geograph.org.uk - 3406885" by Graham Hogg is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

Comparison with Roman sites to the south

One conjecture, is that the Roman Rig line was potentially, at some point the Roman/Brigantian border. If this were correct, then it stands to reason that the Roman forts to the south of Roman Rig, would have a very an establishment date somewhere within our known Brigantian timeline, this might be via a marching camp close to the final fort, or ,if the marching camp was it the right place for the later fort, then we might not see that original marching camp.Looking at the distribution of Roman temporary (“marching”) camps in relation to the line of the Rig and the sequence of forts that lie immediately to its south. What emerges is that, within a c. 10 km corridor either side of the Roman Rig, no genuine Roman marching camps have been securely identified—and yet all of the main frontier forts were laid out directly without an antecedent camp. Here’s the breakdown:

Marching Camps near the Rig

Campsall (unverified)

Location: c. 7 km east of Kimberworth, near the village of Campsall.Status: A “camp” shape has been reported by hobbyists (measured at c. 160 yd × 120 yd), but there is no excavation or professional survey to confirm it as Roman (sheffieldhistory.co.uk).

No other camps have been reliably recorded within 10 km of the Rig’s course—even broad searches of the Well-Mapped “Temporary Marching Camps” datasets turn up none in South Yorkshire (roman-britain.co.uk).

There is no solid evidence for any Roman marching camp fronting the Rig itself.Frontier Forts Immediately South of the Rig

All of the forts built along the Don valley just south of the Rig—Templeborough, Adwick-le-Street (Derventio) and Doncaster (Danum)—share a similar pattern:

Direct foundation was as permanent forts (c. AD 50–80), often with timber ramparts laid out on virgin ground. No precursor marching camp has ever been recorded at or beside any of these sites.

| Fort | Nearest Rig Point | Marching Camp Known? | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wincobank | c. 1 km SW of the Rig | No | Unlikely to be a fort, but used in the 2nd C. perhaps as a look out? (en.wikipedia.org). Probably not relevant, but worth noting. |

| Templeborough | c. 0.5 km S of the Rig | No | Established directly over industrial and vicus zone. |

| Adwick-le-Street | c. 3 km SE of the Rig | No | Auxiliary Fort. |

| Doncaster (Danum) | c. 5 km SSE of the Rig | No | No camp recorded; city grew around fort principia |

Implications for the Rig as a Frontier

If the Rig was a Brigantian boundary or early Roman frontier, the absence of marching camps suggests that the legions never mass-camped directly against it.

Instead, the army appears to have respectfully abutted the existing dyke, constructing permanent forts immediately to its south rather than extending or destroying it with field-works.

This pattern implies a degree of accommodation or continuity with local territorial divisions, rather than a full-scale military assault on the dyke line.

Summary Conclusion

Within the 10 km corridor of South Yorkshire’s Magnesian Ridge, no verified Roman marching camps pre-date the frontier forts that sit on the far side of the Rig. All of those forts—Templeborough, Adwick-le-Street and Danum—were established directly as permanent installations, without evolving from earlier temporary camps. This reinforces the view that the Roman Rig persisted as a meaningful boundary feature—even under Roman rule—rather than being swept away in a campaign of conquest encampments.

Looking at the dates for these forts, I would suggest that these were all built prior to Rome entering Brigantia fully, but within that period mentioned in the records of Tacitus, where Cartimandua was a client queen, and perhaps Venutius had separated from her. This is largely inline with my thinking, but I still wonder if there are other, earlier Roman structures in the area that can tell us something of the earlier Roman activity in the area. This, of course, is conjecture. But I think this is the closest we may get to any kind of firm, pre-Roman Brigantian southern border.

Research, of course, will go on. I need to start checking the chronologies for the Roman forts further north and whether any what marching camps may be associated with them. Distances are straight-line “as the crow flies” from the nearest visible section of the Rig (roughly at Kimberworth, SE 436 937).

| Temporary (Marching) Camp | Location | Distance from Roman Rig | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Newton Kyme | c. SE 505 412 (near Tadcaster) | ~60 km north-north-east | Newton Kyme Camp & settlement romanroads.org |

| Cawthorn | c. SE 757 762 (North York Moors) | ~75 km north-east | Cawthorn Camp overview realyorkshireblog.com |

| Burrow Walls | c. SD 592 765 (Irthington, Cumbria) | ~130 km north-west | Roman camps GIS study bandaarcgeophysics.co.uk |

| Camboglanna (Castlesteads) | Hadrian’s Wall, Cumbria | ~170 km north | Hadrian’s Wall forts |