Arka Unskel hill-fort

(All measurements from the RCAHMS/Canmore archive; no modern excavation report has been published beyond the short interventions listed below.)| Aspect | What can be said with confidence |

|---|---|

| Location | Grid ref. NC 4632 0154, on a craggy boss 175 m OD above the right bank of the River Oykel, 4 km W of Invershin, Sutherland. The knoll commands the mouth of Strath Oykel (east-west fish-salmon route) and has inter-visibility with the Iron-Age broch of Dun Creich on the opposite (southern) ridge. |

| Topographic setting | Igneous epidiorite plug rising 35 m above the surrounding heather moor. Birch–oak scrub clothes the lower slopes; the summit is bare rock with thin podzolic soil (< 0.15 m). Modern environment is open hill-grazing, red-deer estate. |

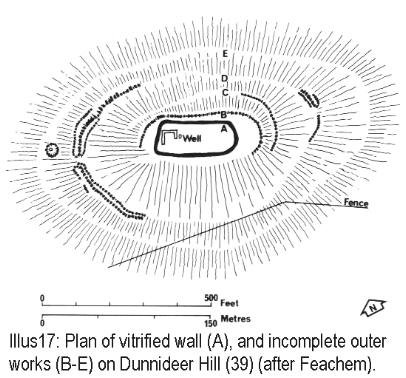

| Earthworks & masonry | An oval stone wall, c. 77 m E-W × 42 m N-S, averages 4–4.5 m thick. The facing stones survive as two to three courses, but the core is a fused, glassy mass up to 1.2 m high – classic vitrification. The best-preserved sector is the north-west Scarp, where globular green glass coats flags and gneiss boulders. A single entrance (2.2 m wide) is visible on the south-east. |

| Outworks | A discontinuous outer rampart of boulder-facing and rubble survives on the gentler western and southern slopes, 12–15 m outside the inner wall, but is not vitrified. |

| Excavation & dating |

|

| Finds | Extremely sparse: two coarse hand-made sherds (likely Late Bronze-Age), an iron slag prill, and several fragments of vitrified stone with oak charcoal sealed in vesicles. No datable artefacts later than c. 4th century BC have been recovered. |

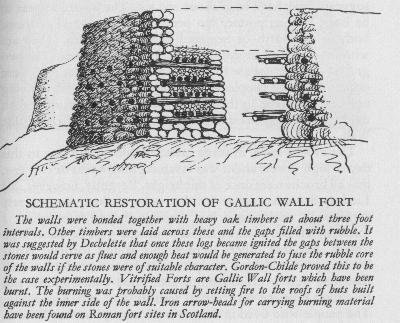

| Interpretation of vitrification | The timber-laced construction implied by beam-sockets and charcoal, combined with laboratory melting temperatures and the wall-thickness (4 m), agree with other purpose-fired Highland forts (Tap o’ Noth, Craig Phàdraig). Whether the firing was an aggressive destruction or a ritualised “closure” remains open; lack of sling-stone banks or arrowheads slightly favours a controlled burn. |

| Environmental context | Palaeoenvironmental cores 500 m north (Oykel flood-plain fen) show a peak in microscopic charcoal and a decline in oak/pine c. 350 BC, consistent with woodland clearance for rampart firing. Later pollen curves regain oak and birch dominance, suggesting the fort was not re-occupied intensively after the conflagration. |

| Later history & land-use | No Pictish or Norse artefacts recorded; the vitrified ruin appears on Timothy Pont’s map (~1590) as “Arka Unskel Castellum ruinosum”. The knoll became a mediaeval shieling stance and is now managed as Scheduled Monument (SM 2855). |

Research potentials

- High-resolution magnetometry could identify internal round-house gullies or metal-working floors hidden beneath collapsed wall tumble.

- OSL or additional radiocarbon dating from the vitrified core might tighten the firing episode to a 50-year window.

- Lead-isotope assays on any slag lumps could reveal whether the site smelted local Strath Oykel bog-iron immediately before its destruction.

Wider significance

Wider significance

Arka Unskel occupies a strategic saddle node between coastal Dornoch Firth farming ground and the upland glens of Ross-shire. Together with Dun Creich broch and the vitrified forts of Craig Phàdraig, Dun Lagaidh and Tap o’ Noth, it forms part of a chain of Mid-1st-millennium BC fortified high points that guard salmon-rich river mouths and drove-road corridors. Its near-complete vitrified curtain makes it a textbook example of the Highland “fire-fort” phenomenon and an invaluable control for experimental melting studies.

From Richard Feachem's "A guide to Ancient Scotland"-

"At the point where Loch na Nuagh begins to narrow, where the opposite shore is about one-and-a-half to two miles distant, is a small promontory connected with the mainland by a narrow strip of sand and grass, which evidently at one time was submerged by the rising tide. On the flat summit of this promontory are the ruins of a vitrified fort, the proper name for which is Arka-Unskel.

Vitrified Fort

The rocks on which this fort is placed are metamorphic gneiss, covered with grass and ferns, and rise on three sides almost perpendicular for about 110 feet from the sea level. The smooth surface on the top is divided by a slight depression into two portions.

On the largest, with precipitous sides to the sea, the chief portion of the fort is situated, and occupies the whole of the flat surface. It is of somewhat oval form. The circumference is about 200 feet, and the vitrified walls can be traced in its entire length.

We dug under the vitrified mass, and there found what was fascinating, as throwing some light on the manner in which the fire was applied for the purpose of vitrification. The internal part of the upper or vitrified wall for about a foot or a foot-and-a-half was untouched by the fire, except that some of the flat stones were slightly agglutinated together, and that the stones, all feldspathic sandstone, were placed in layers one upon another.

It was evident, therefore, that a rude foundation of boulder stones was first formed upon the original rock, and then a thick layer of loose, mostly flat stones of feldspathic sandstone, and of a different kind from those found in the immediate neighbourhood, were placed on this foundation, and then vitrified by heat applied externally.

Arka-Unskel is not only remarkable for its natural beauty but also for its historical importance, particularly in relation to Bonny Prince Charlie, a central figure in the Jacobite uprising. The prince is said to have landed at Arka-Unskel before the ill-fated Battle of Culloden in 1746, which was the last pitched battle fought on British soil and marked the end of the Jacobite attempt to restore the Stuart monarchy to the British throne.

The battle was a decisive victory for the British government forces, and it led to the brutal suppression of the Highland way of life and the clan system.

The landing of Bonny Prince Charlie

The significance of Arka-Unskel lies not only in its connection to this pivotal moment in history but also in its archaeological features. The site contains the ruins of a vitrified fort, a rare type of construction where the stone walls have been fused together by intense heat.

The process of vitrification remains somewhat of a mystery to archaeologists, but it is believed to have been a deliberate act, possibly for strengthening the structure or as a display of power. The fort at Arka-Unskel, with its heavily vitrified wall, is a testament to the ingenuity and craftsmanship of the ancient peoples of Scotland.

The landing of Bonny Prince Charlie at Arka-Unskel is a narrative that adds a layer of depth to the site's history, intertwining the natural and the man-made, the ancient and the relatively recent. It serves as a reminder of the complex tapestry of Scotland's past, where each thread represents a story of struggle, innovation, and resilience."