Contents

- 1 East Yorkshire

- 2 Prehistoric timeline & key sites

- 3 How the pieces fit together

- 4 The Arras culture of East Yorkshire

- 5 What we know (and what we can only infer) about Parisii-Brigantian relations

- 6 Why the region matters archaeologically

- 7 Square Barrows in Brigantia?

- 8 Points to underline

- 9 Linked Documents

- 10 All Saints Church, Rudston

- 11 Rudston Standing Stone

"Flamborough Head" by naturalengland is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

East Yorkshire

| Layer | Main features | Why it matters |

|---|---|---|

| Geography |

A coastal county that runs from Spurn Point in the south to the hard-chalk headland of Flamborough in the north.

|

The belts dictate land use and settlement: sheep-corn on the Wolds, market gardening and transport corridors in the vale, dispersed villages that retreat landward on the crumbling Holderness coast. |

| Geology | The Wolds are made of Late-Cretaceous Chalk, Britain’s most northerly outcrop. (earthwise.bgs.ac.uk) The Vale of York is underlain by Jurassic mudstones but smothered in glacial tills and outwash. Holderness plain = Devensian boulder clay; permeable sands cap Spurn spit.• Pockets of Permian Limestone and coal measures fringe the Humber. (Wikipedia) | Chalk filters ground-water, making spring lines that sited Neolithic and Roman farms; the soft boulder-clay cliffs explain the area’s dramatic coastal loss and shifting ports. |

| Heritage & post-Roman history | Roman: Petuaria (Brough) and a signal-station chain on Flamborough. Anglo-Saxon: royal centre at Goodmanham; monasteries at Beverley and Whitby influence the Wolds. Medieval: Beverley Minster (13th c.) and Bridlington Priory dominate the ecclesiastical landscape. (beverleyminster.org.uk) Late-medieval/early-modern: Kingston-upon-Hull (chartered 1293) grows into England’s third port.Industrial: whaling, fishing and–later–North Sea oil out of Hull; drainage schemes turn Holderness marsh into prime arable land. | Shows a swing from inland royal/monastic power to maritime trade, all framed by the county’s ready river and sea access. |

"Skipsea Castle 1" by JThomas is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

Prehistoric timeline & key sites

| Period | Date range (cal BC) | Representative site(s) | What makes them important |

|---|---|---|---|

| Palaeolithic & Mesolithic | >12 000–4000 |

Isolated flint bladelets and scrapers at Sunk Island, Welton Wold and Skipsea Till exposures. A single tanged point from the Holderness coast reported by Evans (2020). A small in-situ scatter on a buried soil at Fraisthorpe (English Heritage archive). |

Finds are edge-of-Holderness or Wolds spring-line scatters; they hint at passing hunter-gatherer bands following the Humber wetlands and Wolds chalk springs. No cave sites exist in the county’s chalk, so Creswell-style evidence is absent. |

| Early–Middle Neolithic | 4000–3000 | Kemp Howe Long Barrow, Warter Wold; cursus crop-marks near Rudston. | Long Barrows and cursus monuments show the Wolds integrated into the wider Yorkshire–Wessex ritual zone. |

| Late Neolithic / Early Bronze Age | 3000–1500 | Rudston cursus group & monolith; Danes Graves Round Barrows. | Rudston monolith (7.6 m) is Britain’s tallest standing stone; barrow cemeteries align ridge-top trackways. |

| Middle–Late Bronze Age | 1500–800 | Brown Moor field systems; dirk hoards at Driffield. | Field dykes running over the Wolds chalk mark an intensification of arable farming. |

| Middle Iron Age (Arras culture) | 400–100 | Arras Farm cemetery, Wetwang Slack chariot burials, Garton Slack square barrows. (Wikipedia, stone-circles.org.uk) | Square ditched barrows with chariots and brooches give East Yorkshire its own La Tène-style identity. |

| Late Iron Age / Conquest horizon | 100 BC – AD 70 | Staxton–Flixton Promontory forts; finishing/post-Conquest hoards. | Defensive sites overlook the Vale and coast; coin hoards suggest instability during Roman advance. |

How the pieces fit together

Chalk Wolds as a prehistoric spine – every major monument from barrows to square-ditched graves sits on or beside the chalk ridge, where light soils, flint raw material and commanding views coincide.

Holderness is left almost a blank – deep till and frequent marine incursions kept early farmers away; only later medieval drainage unlocks the plain.

Arras culture uniqueness – nowhere else in Britain adopted the square-barrow and chariot-grave habit so intensively; it speaks to strong continental links via the Humber–Ouse–Rhine maritime highway.

Continuing coastal dynamism – from the lost Roman signal-station at Dimlington to modern retreats at Spurn, the soft east coast continually rewrites the county’s boundary and reshapes its heritage in real time.

These layers; chalk uplands, eroding clay coast, square-barrow cemeteries, monastic Gothic, and Victorian docks, map East Yorkshire’s journey from thinly settled high ground to a maritime gateway that still balances agricultural heartland, industrial port, and fragile edge of England.

"North Grimston Sword, Late 2nd Century BC" by Humber Museums Partnership is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

The Arras culture of East Yorkshire

East Yorkshire’s Middle-Iron-Age story stands out in Britain because the communities who farmed the chalk of the Yorkshire Wolds developed what archaeologists call the Arras culture: a distinctive blend of continental La Tène fashions and local invention that is visible above all in their cemeteries. Three elements make it special.

Square-ditched barrows: a unique British rite

Most Iron-Age burials south of the Forth–Clyde are placed in flat graveyards or reused Bronze-Age round barrows. On the Wolds, however, the dead were interred in brand-new square (or slightly rectangular) ditched enclosures—hundreds of them, laid out in organised fields at Arras, Garton Slack, Danes Graves, Pocklington and Wetwang. The idea comes straight from north-eastern France and Belgium, yet nowhere else in Britain adopted it so comprehensively. The plan itself symbolises control and order; placing a fence-like ditch around a single grave elevated family identity in a way previously unseen in Britain. (Wikipedia)

Chariot burials and the warrior-elite image

In a handful of square barrows, an adult (sometimes male, sometimes female) was laid on or beside a dismantled two-wheeled chariot—wheels upright, pole pointing south, horses occasionally buried too, as seen at Wetwang Slack and Pocklington. Outside East Yorkshire the only British parallels are two Scottish graves and a stray example near Leeds; on the near Continent the rite marks high-status “princely” burials. Its presence on the Wolds signals direct contact with Champagne and the Marne, and it promoted a public image of mobile, conspicuous warriors who could appear suddenly on the landscape—perfect for the open downland of the Wolds. (Wikipedia, The Past)

Grave goods that fuse local and continental fashions

Arras graves mix La Tène brooches and horse-gear with objects that feel intensely local: turned wooden cups, boar-tusk ornaments, chalk spindle-whorls. Isotope and radiocarbon work at Wetwang shows the chariot horizon was short-lived—around 250–150 BC—but created a hybridised style whose influence lingers in the wider region’s art and metalwork. The hybrid kit tells us the Wolds people were not passive recipients of prestige imports; they re-edited continental signals into a distinct North-Sea identity, perhaps to brand themselves as the “people of the Humber gateway.” (ResearchGate)

Lasting importance

Because Arras-style graves freeze the moment when continental and British lifeways meshed, they provide Britain’s clearest window onto cross-Channel politics in the two centuries before Rome. The cinematic quality of the finds—chariots, harness, sometimes even horses—still shapes public imagination of the Iron Age, and the research potential remains high: every new housing development on the Wolds is watched for the next square ditch that might reveal another member of this unusually visible, short-lived warrior aristocracy.

What we know (and what we can only infer) about Parisii-Brigantian relations

| Evidence base | What it tells us | Implications for the relationship |

|---|---|---|

| Classical geography – Ptolemy (c. AD 150) places the Parisi east of the Brigantes, around a “good harbour” usually taken to be the Humber/Brough area. He lists the tribes separately. (Wikipedia) | By Ptolemy’s day the Parisii were regarded as a distinct polity, not simply a Brigantian sub-district. | Political autonomy at least in the 2nd century AD. |

| Size and setting – Parisii territory is a narrow wedge (the Yorkshire Wolds and Holderness coast) hemmed in by the much larger Brigantian zone to the west. (University of Warwick, The Time Travellers) | Small tribes often survive by alliance or client status to a bigger neighbour. | A client or partner arrangement with the Brigantian federation is plausible. |

| Material culture – The Parisi are equated with the Arras culture: square-ditched barrows and occasional chariot burials unique in Britain. These customs have also been found in Brigantia, but typically in fringe areas. | Distinctive funerary ideology suggests the Parisii maintained a separate identity even if politically linked. | |

| Continental links – Arras burials mirror La Tène cemeteries in Champagne; the tribe’s name echoes the Gallic Parisii of the Seine. | East-coast trade down the Humber could have given the Parisii direct continental contacts independent of Brigantia. | The Parisii may have looked outward to the North Sea network rather than west to Brigantian uplands. |

| Brigantian revolt (AD 69–74) – Venutius’ anti-Roman rising swept parts of Yorkshire, yet the Brough (Petuaria) area shows no destruction horizon. | Either the Parisii stayed neutral or their zone was spared, hinting they were not tightly bound into Brigantian politics by that date. | |

| Roman administration – Under Rome, the Parisii area becomes a small civitas Parisiorum with its own centre at Petuaria; the Brigantes are broken into several larger civitates. | Rome formalised the tribal split it found rather than carving it artificially. | Confirms separate civil status after conquest. |

An assumed working model

Before Rome (c. 300–50 BC)

The Wolds elites cultivate continental ties (chariot rite), probably exchanging metal and salt down the Humber. The Brigantian highlands to the west form a looser federation of upland communities. Relationship: friendly neighbours; Parisii small enough to acknowledge Brigantian over-king-ship in times of war or ceremony, but culturally distinct.

Early Roman contact (AD 40s–70s)

Rome negotiates first with the Brigantian court (Cartimandua, Venutius); Parisii zone appears quiet, suggesting indirect rule via Brigantia or early accommodation with Rome. Relationship: Parisii perhaps clients of the Brigantian queen, later peel away as Rome undermines Brigantian unity.

Under Roman rule (2nd–4th c.)

The Humber crossing becomes a supply route (Petuaria–York road). Parisii civitas handles coastal trade; Brigantian territory subdivided into larger civitates. Relationship: administrative separation fixed; cultural blending increases, and Arras-style burials fade.

Why the region matters archaeologically

Square barrows and chariot interments set the Parisii apart from every other British tribe, so East Yorkshire is a laboratory for studying continental interaction.

Brigantian uplands provide contrasting settlement forms (round farmsteads, hilltop enclosures) that let researchers test how political boundaries map—or fail to map—onto cultural ones.

Square Barrows in Brigantia?

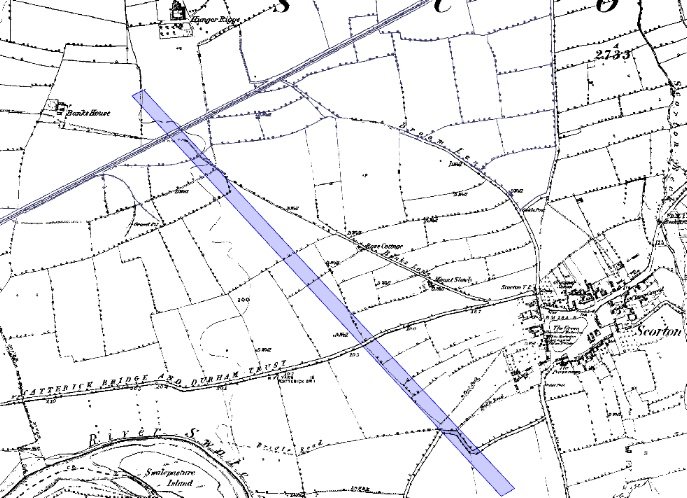

Square-ditched barrows are not only confined to the Wolds/Arras core area; smaller clusters and isolated examples have been reported occur across what was Brigantian territory.Potential (require further investigation) square-barrow occurrences within Brigantian territory

| Site & county | Secure evidence | Status of publication | Why it matters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ferry Fryston, West Yorkshire | 2003 A1(M) junction works exposed a dismantled chariot burial in a 7 m square ditch; Beaker‐shaped barrow fill and La Tène harness fittings. | Detailed monograph: Mel Giles & C. Haselgrove 2024; summary in museum blog. (Great North Road) | First out-of-Wolds chariot burial; proves Arras funerary rite travelled 35 km west onto Magnesian Limestone. |

| Nosterfield Quarry, N Yorkshire | 1996–2004 gravel extraction recorded two square barrows (8 m & 10 m), both containing flexed inhumations; Wetwang-type brooch in Barrow 2. | Initial interim (On-Site Archaeology 2004); synthetic article on BrigantesNation 2025. (The Modern Antiquarian) | Only confirmed square barrows in the Swale-Ure Interfluve; extend Arras horizon north-west of the Vale of York. |

| Thorpe Audlin, West Yorkshire | Evaluation (1993) and geophysics located a paired square-barrow cluster beside a later Romano-British enclosure; single crouched burial recovered. | R. Van de Noort 1995, Yorkshire Archaeological Journal 67. (Archaeology Data Service) | Shows the rite skims the magnesian ridge south of the Aire. |

| Scorborough Hall, East Yorkshire (Holderness edge) | Scheduled monument 1015613: at least 17 square barrows within a mixed cemetery that also has round barrows and medieval earthworks. | Historic England schedule description; no modern excavation. (Historic England) | Outlier east of the Hull Valley—bridges Arras core and Humber south bank. |

Points to underline

Rarity, not absence: outside the chalk Wolds the square-barrow evidence is sparse but real, there are roughly two dozen confirmed examples versus a thousand on the Wolds.

Edge-of-corridor positioning: every Brigantian-zone barrow sits on a transport corridor (A1, Humber/Ouse, ancient ridgeway) where Wolds elites and inland groups could meet. Status signalling: where grave goods survive (Ferry Fryston, Nosterfield) they echo Arras high-status markers (chariot parts, La Tène brooches), implying the outliers mark individuals who wanted that Wolds/continental badge of identity.Linked Documents

All Saints Church, Rudston

Rudston Standing Stone