Kirkhaugh Cairns

Barrow (NY 704494) 2 miles NNW of Alston. Finds in Museum of Antiquities, Newcastle.Location

Kirkhaugh Cairns form one of the most intriguing Early Bronze-Age funerary complexes in northern England, renowned for the spectacular “hair-braid” gold rings found in association with a metal-worker’s burial. Situated in South Tynedale, they occupy a gentle terrace on the south bank of the River South Tyne (OS grid NY 785 874; 54.839° N, –2.239° W), approximately 3 km northwest of Alston and just northeast of the Roman fort at Epiacum (en.wikipedia.org).

Geology and Landscape

The cairns sit within the North Pennine ore-field, underlain by Carboniferous limestones and sandstones cut by rich veins of copper and lead. The broad Tyne valley here is floored by fluvioglacial gravels and alluvium; to the north and south the land climbs steeply into heather-clad moorlands, where small springs emerge at the Limestone-Shale junctions. This setting provided both accessible water for ore-processing and easy access to metal-bearing rocks on the adjacent fells (researchframeworks.org).

"Knarsdale and Kirkhaugh Cairns Community Hall - geograph.org.uk - 3343381" by Les Hull is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

Site Description

Originally, two, and possibly three, round cairns stood in a linear group, each about 6–8 m in diameter and up to 1 m high. The turf-covered stone mounds once overlay rock-cut sockets and packed stone burial chambers. By the mid-20th century, ploughing and reservoir works had damaged parts of the group, but the two principal mounds remained identifiable.

1935 Excavation (Herbert Maryon)

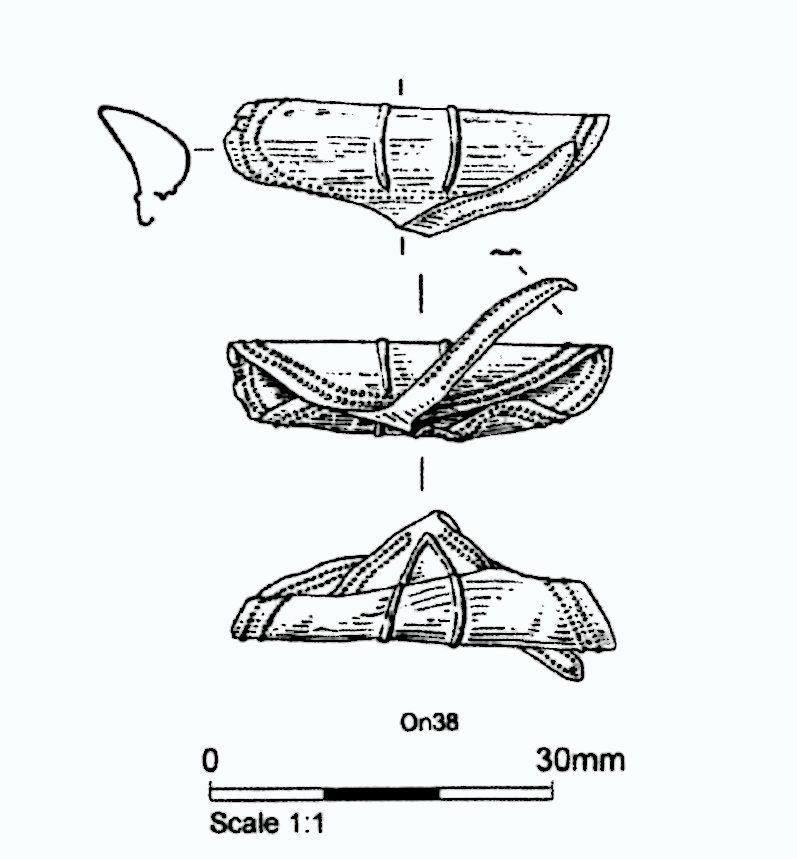

Over five days in September–October 1935, Herbert Maryon (Durham University) and Joseph Alderson opened Cairn 1. Beneath a “continuous layer of flattish stones” they recorded patches of greasy clay on the bedrock - suggestive of a decayed organic burial. They recovered a suite of grave-goods clustered in a central 3–4 m area. Finds included a crushed food-vessel (later identified as an early Bell-Beaker pot), flint tools, a lump of pyrite, a sandstone hone, and notably one small gold “ear-ring,” now reinterpreted as a hair-braid ring, it's typology being of those found with the Amesbury Archer, which are among the earliest gold objects in Britain.

Cairn 2, opened in the same campaign, proved empty. No human remains survived, but the presence of the high-status goods in Cairn 1 strongly suggests a metal-worker of Bell-Beaker affiliation was commemorated here around c. 2400 BC (researchframeworks.org).

"Kirkhaugh cairn gold ornament" by The Portable Antiquities Scheme is licensed under CC BY 2.0 |

"Kirkhaugh cairn gold ornament diagram" by Durham County Council is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 |

2014 Community Re-excavation and Survey

Under the Altogether Archaeology programme, volunteers and Durham University’s Archaeological Services returned to Kirkhaugh in 2014. Detailed geomagnetic and resistivity surveys mapped the buried cairn footprints and revealed surrounding field-boundary ditches (northpennines.org.uk). During small-scale re-excavation of Cairn 1, four local schoolboys—two of whom were descendants of Alderson’s helpers—uncovered a matching gold hair-braid ring in situ, confirming that the original metalworker grave was deliberately furnished with a rare pair of braid-rings (bajr.org).

Interpretation and Significance

The twin braid-rings and Bell-Beaker vessel align Kirkhaugh with the broader network of Early Bronze-Age metal elites (cf. the Amesbury Archer). Their deliberate deposition at a prime ore-field locus implies that specialist metallurgists anchored themselves here to exploit local copper and lead veins. Perhaps training apprentices and forging regional trading ties. The fact that one cairn was left empty while the other contained rich goods suggests nuanced funerary choices, possibly reflecting status or professional affiliation.

Local Features of InterestEpiacum Roman Fort: Just below the cairns, this large fort (Whitley Castle) controlled lead-mining in the Roman period. Its proximity underscores Kirkhaugh’s long-term strategic value.

South Tyne Trail: A public footpath now passes the cairns, offering views of the moorland skyline and access to interpretive panels on the site’s history.

Cup-and-Ring Carvings: Scattered panels on nearby outcrops link the cairns to a wider ritual landscape of rock art across the Pennines.

| "This mound is 22ft. in diam. and about 3ft high. It has been built upon a natural knoll which makes the barrow look larger than it is. Excavation showed that the mound has an earthy core with a rubble capping. Decayed traces of an unburnt body were found at the centre and among the offerings in the mound near the burial there was a basket-shaped gold ear-ring of a type found with beakers in Britain. Date, c. 2,000 - 1,700 BC. |

Importance of the "Hair-Braids"

The tiny gold “hair-braid” rings of the Early Bronze Age are among the rarest and most telling artifacts to survive from Britain’s prehistoric past. Far from mere personal ornaments, these finely wrought loops were the insignia of a highly specialized elite—master metalworkers whose skills in copper and gold defined a new social order around 2400 BC. Found only in a handful of burials—most famously with the Amesbury Archer in Wessex and in upland cemeteries at Kirkhaugh, and Boltby Scar—each braid‐ring appears alongside copper tools, fire-steel nodules and distinctive Beaker pottery, marking its owner as part of a tightly knit craft “guild.”

What truly sets these sites apart is their deliberate siting at prime ore sources. Kirkhaugh Cairns lie in the heart of the North Pennine copper-lead fields, Boltby Scar overlooks early Roulston Moor workings, and the Archer’s Wessex homeland linked into continental exchange routes. By anchoring themselves where raw materials were most accessible, these metalworkers not only oversaw smelting and alloying but also trained local apprentices, spreading both technology and its ritual aura across the British Isles.

The arrival of the Amesbury Archer—a man whose strontium-isotope signature traces his youth to the Western Alps—heralded a wider cultural influx. His grave, laden with the earliest gold ever found in Britain, speaks to the importation of Bell-Beaker metallurgical traditions and high-status burial rites. These continental connections dovetailed with an island-wide “revolution” in which metal, monument and memory fused.

Nowhere is that fusion more dramatically enshrined than at Stonehenge. Built in phases from around 2600 to 2400 BC—well after the first Atlantic stone alignments—its massive trilithons and imported bluestones echo the same networks of mobility that brought gold and copper to Britain’s elites. The monument’s circular Henge and precise stone engineering can be seen as the apogee of a social transformation initiated by those metal-working masters.

Finally, radiocarbon evidence shows that these braid-rings were always deposited in death—ceremonially “retired” in tombs and never recycled. This collective act of deposition, repeated across distant regions, points to a shared cosmology: a belief that the ultimate resting place for these symbols of craft and power lay beneath the earth. Though their makers have vanished into prehistory, the gold hair-braids remain silent testimony to an age when metallurgy and monumental architecture reshaped Britain’s cultural landscape.

References

Herbert Maryon’s 1936 excavation report

Maryon, H. (1936). “Excavation of two Bronze Age barrows at Kirkhaugh, Northumberland.” Archaeologia Aeliana 4th Series, 14: 1–20.

Where to find it: Any good university library with back-runs of Archaeologia Aeliana, or via inter-library loan.

Durham University geophysical survey

Archaeological Services Durham University (October 2014). Kirkhaugh Cairn, Tynedale, Northumberland: Geophysical Survey Report.

Where to find it: Archived on the Durham University Archaeological Services website or by request to ASDU.

Altogether Archaeology newsletter item

Jeeves, P. (4 August 2014). “Schoolboys unearth golden hair tress more than 4,000 years old.” Altogether Archaeology, Issue 6.

Where to find it: Available from the Altogether Archaeology website’s back-issue archive.

Historic England PastScape entry

PastScape Monument No. 26933, “Kirkhaugh Cairns, barrow cemetery.”

Where to find it: Online at the Historic England PastScape database (search by monument number).