Contents

- 1 Cumbria

- 2 Quaternary Glaciation and Modern Topography

- 3 Human Interaction with the Landscape

- 4 Linked Documents

- 5 Castlerigg stone circle

- 6 Dunmallard Hill Fort

- 7 Hardnott Roman Fort

- 8 King Arthurs Round Table Henge

- 9 Kirkhaugh Cairns – Cumbria

- 10 Little Meg Stone Circle

- 11 Long Meg and her Daughters standing stone and stone circle

- 12 Maiden Castle Fort Pooley Bridge

- 13 Mayburgh Henge

- 14 Troutback Roman Camps

- 15 Whitley Castle Roman Fort (Epiacum)

Cumbria

Cumbria’s dramatic landscapes are the product of a 500-million-year geological saga, punctuated by mountain-building, volcanic upheaval, Limestone burial, tectonic extension and, finally, repeated ice-age sculpting. Today it can be divided into four broad physiographic regions.

The Lake District Massif

At the heart of Cumbria lies the Lake District—a roughly oval block of Ordovician and Silurian rocks intruded by Devonian granites. The oldest sediments (Skiddaw Group mudstones and siltstones) form the northern fells, while the central core—the Borrowdale Volcanic Group—consists of hard lavas and ash flows that give rise to the highest peaks (Scafell Pike, Helvellyn). Underneath, a suite of granitic intrusions (Eskdale, Ennerdale, Shap granites) once fed surface volcanoes; those plutons now underlie much of the central plateau. Later Silurian slates and sandstones cap the lower flanks on the south and east margins (en.wikipedia.org, englishlakedistrictgeology.org.uk).

The Carboniferous Margins and Pennine Front

Surrounding the volcanic core to the north, east and south is a horseshoe of Carboniferous sedimentary rocks: thick limestones of the Carboniferous Limestone Supergroup, followed upsection by Millstone Grit sandstones and Coal Measures Shales. These form the gentle hill country of the Vale of Eden and the high moorland plateaux of the North Pennines. The eastern edge of this belt is defined by the steep Scarp of the Askrigg Block, giving rise to ridges like Cross Fell. This limestone-sandstone succession underpins fertile pastures, upland grass moors and the great Dales river valleys (cumberland-geol-soc.org.uk, geolsoc.org.uk).

The Vale of Eden and Border Lowlands

The Vale of Eden itself is a narrow, fault-bounded half-graben that separates the Lake District from the Pennines. Here Permo-Triassic sandstones and breccias (Appleby Group, local “Brockram”) overlie eroded Carboniferous beds, producing a gently rolling flood-plain through which the River Eden flows northward toward the Solway Firth. To the west and south lie low-lying Drumlin fields and coastal plains of West Cumbria and Furness, where glacial till and post-glacial sediments cap older rocks (geolsoc.org.uk, pubs.geoscienceworld.org).

Quaternary Glaciation and Modern Topography

From about 2.6 million to 11,700 years ago, repeated Pleistocene glaciations carved Cumbria’s present form. Thick ice sheets flowed out from the Lake District and Pennines, scouring U-shaped valleys, over-deepening basins (now occupied by Windermere, Ullswater and Derwentwater) and depositing Moraines that dammed tributary valleys. On the coastal fringe, glacio-fluvial gravels and raised beaches record ice margins and post-glacial sea-level changes. The result is the iconic contrast of craggy fells, ribbon lakes and tiered valley sides that defines Cumbria today (en.wikipedia.org, cumberland-geol-soc.org.uk).

Human Interaction with the Landscape

Humans have been reshaping Cumbria’s landscape for at least 12,000 years, leaving a rich mixture of sites that track changing economies, beliefs and social structures.

Mesolithic Foragers and the First Occupation

The earliest evidence comes from Late Upper Palaeolithic and Mesolithic hunter-gatherers exploiting coastal and riverine resources. At Maryport on the Solway Plain, excavations uncovered worked flint and tuff tools dating to the Final Palaeolithic Federmesser groups, around 11,000 BC (intarch.ac.uk). Similar microlith assemblages in cave deposits at Netherhall Road, Allithwaite, show Mesolithic foragers seasonally visiting limestone outcrops to hunt red deer and gather hazelnuts, leaving charcoal peaks in peat profiles as silent testimony to their campfires (intarch.ac.uk).

Neolithic Farmers and Monument Builders

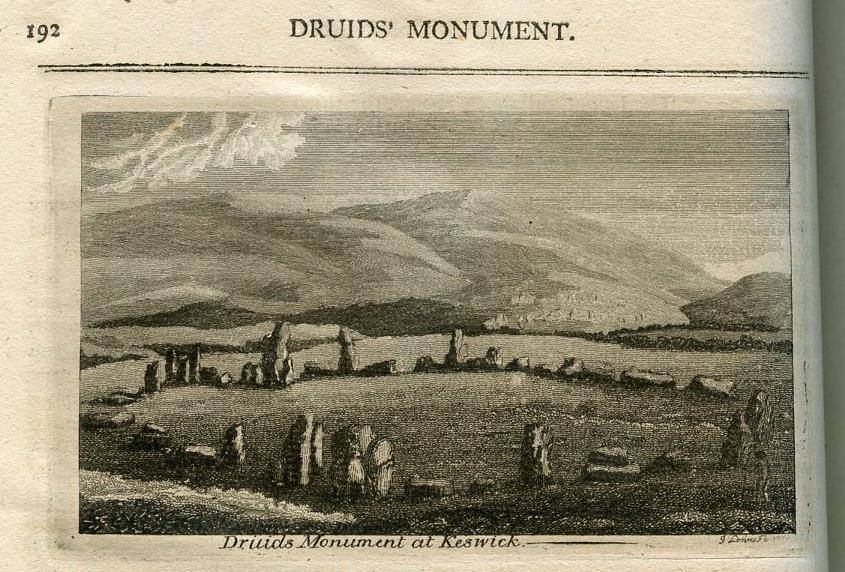

From around 4000 BC, Neolithic farmers began clearing forest for grazing and cultivating small cereal plots. They also erected some of Britain’s most evocative megaliths: the Langdale axe “factory” at Pike o’ Stickle supplied polished greenstone axes traded as far away as Norfolk and Northern Ireland, while the Castlerigg Stone Circle (c. 3000 BC) crowns a natural amphitheatre beneath Skiddaw, its 38 erratic boulders aligned to sunrise views (english-heritage.org.uk). On the low limestone plateau near Penrith stand the massive Mayburgh Henge and King Arthur’s Round Table, Earthwork circles that defined communal ritual spaces amid the budding pastoral economy (en.wikipedia.org).

Bronze and Iron Age Communities

By 2500 BC, metallurgy arrived via Bell-Beaker networks, and small Cairn cemeteries—like Kirkhaugh on the South Tyne—commemorated specialist metal-workers interred with gold hair-braids and copper tools . Iron-Age farmsteads and hill-forts—such as Maiden Castle near Pooley Bridge—then dotted the fells, their univallate ramparts and hut platforms integrating upland grazing with strategic oversight of valleys below .

"Hadrian's Wall - Sept 2014 - Bleak Housesteads" by Gareth1953 All Right Now is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Roman Frontiers and Provincial Integration

From AD 122, Cumbria lay on Rome’s north-western frontier. Hadrian’s Wall stretches 117 km from Bowness-on-Solway to Wallsend, with forts at Birdoswald, Chesters and Housesteads guarding the wild moorland (geographical.co.uk). Along the Solway coast, mile forts and a Roman cremation cemetery at Mile fort 15 attest to a mixed military and civilian presence trading local metals and fish for Samian ware and bronze brooches (en.wikipedia.org).

Medieval to Modern Transformations

After Rome’s retreat, Cumbria evolved through Anglian and Norse settlement, leaving place-names and enclosure patterns in the Eden and Derwent valleys. Castles—most prominently Carlisle and Brougham—anchor medieval lordship and border conflicts.

From the 17th century, the same veins that had drawn Bronze-Age smiths fuelled a booming lead and zinc industry in Alston Moor and Nenthead, leaving spoil-heaps and ruined Engine-houses that, alongside railways and quarries, transformed the landscape.

Linked Documents

Castlerigg stone circle

Dunmallard Hill Fort

Hardnott Roman Fort

King Arthurs Round Table Henge

Kirkhaugh Cairns – Cumbria

Little Meg Stone Circle

Long Meg and her Daughters standing stone and stone circle

Maiden Castle Fort Pooley Bridge

Mayburgh Henge

Troutback Roman Camps

Whitley Castle Roman Fort (Epiacum)