Celtic Heads

Celtic Head from Witham, 2nd c B.C. (British Museum) "Celtic" carved heads are found throughout the Read more

Timeline 60BC – 138AD

This timeline is focussed on the British Celtic culture and those cultures which had influence on the British Celts. It Read more

Cartimandua

Yorkshire, and much of northern Britain was also ruled by a queen, the most powerful ruler in Britain in fact. Read more

Caratacus

Caratacus was highly influenced by the Druids, and both he and his brother Togodumnus were among the leading lights of Read more

Cerialis Petillius

Quintus Petillius Cerialis Caesius Rufus was the son-in-law of Vespasian Cerialis and became Governor of Britain in AD.71; his instructions Read more

Julius Caesar

Ask anyone to name a famous Roman character, and the name of Julius Caesar is sure to be the most Read more

Vespasian

Born in the year 9 at Reate, north of Rome, Vespasian was the son of a tax collector, Flavius Sabinus Read more

Augustus

Suetonius wrote of him: He was very handsome and most graceful at all stages of his life, although he cared Read more

Claudius

Tiberius Claudius Nero Germanicus was born Lugunum in 10 BC, the youngest son of Nero Drusus, brother of Tiberius. He Read more

Celtic Gods

Many Celtic deities seem to have been associated with aspects of nature and worshipped in sacred groves. Some appear in Read more

Syncretism is where two or more differing beliefs become merged. In England, this first happened under Roman rule, where many pre-existing Celtic shrines to specific deities were associated with Roman deities of the same qualities or attributes. Based on extensive research, I am now confident that in Britain, the early Christians undertook a similar process and with that knowledge, we should be able to reverse engineer, to some extent, our local Brigantian Celtic pantheons.

Before I do that, I thought I would write an article on the extent of Syncretism in the Christian church in Europe, to back up some future articles I am planning, where I hope to reveal some specific deities and locations of worship in Brigantia.

This also intertwines with my recent article on the development of the Christian religion in the North of England, which suggests that this early syncretism may well have incorporated Norse and Saxon traditions.

Why did the early Christians syncretize with other religions?

The syncretism observed in early Christianity, where elements of Roman, Hellenistic and other religions were integrated into Christian practices, can be attributed to various factors. The early Christians, living within the vast expanse of the Roman Empire, were influenced by the prevailing cultural and religious norms of their time. The Roman Empire was a melting pot of cultures and religions, and the fusion of these diverse beliefs was commonplace, as seen in the religious syncretism during the Hellenistic period. This cultural milieu would have made it natural for early Christians, many of whom were Romanized in their way of life and thought, to incorporate familiar elements into their new faith.

Moreover, the strategy of syncretism might have been a pragmatic approach to facilitate the acceptance of Christianity among a population steeped in polytheistic traditions. By adopting certain pagan practices and reinterpreting them within a Christian framework, the early Church could make Christianity more accessible and less alien to potential converts. This is evident in the adoption of certain festivals and the Christianization of existing pagan temples. The early Church Fathers, while formulating Christian doctrine, were also influenced by the philosophical thought of the time, which was itself an amalgamation of various cultural philosophies, further contributing to the syncretic nature of early Christian theology.

Additionally, the political landscape of the Roman Empire played a significant role. The conversion of Emperor Constantine and the subsequent Edicts of Milan not only legitimized Christianity but also paved the way for its spread throughout the empire. Constantine’s conversion can be seen as a turning point, where Christianity began to absorb and transform the Roman cultural and religious practices into its own. The Roman infrastructure, such as roads and communication systems, facilitated the dissemination of Christian teachings, while the Roman administrative structure provided a model for the early Church’s hierarchy.

The impact of the Roman’s in Britain

In Roman Britain, the religious landscape was a rich tapestry of beliefs and practices, reflecting the diverse cultures within the Roman Empire. Alongside the emerging Christian faith, a multitude of deities from the classical Roman pantheon were worshipped, including Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva. These gods represented various aspects of life and the universe, and their worship often involved elaborate rituals and offerings at temples and altars throughout the province.

The Romans also practised the Imperial Cult, which involved the veneration of the emperor as a divine figure. This form of worship was not only a religious act but also a demonstration of political loyalty and social status. Participation in the Imperial Cult was sometimes a prerequisite for certain privileges and advancements within the Roman societal structure.

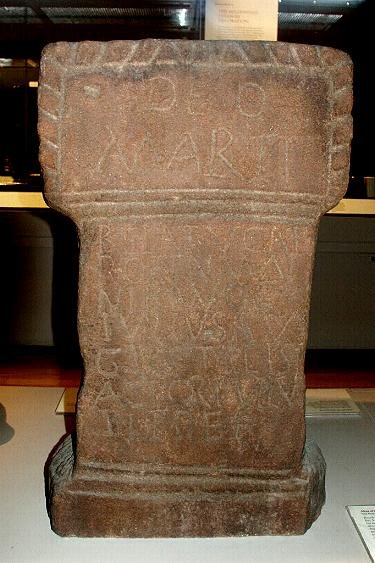

Local Celtic deities continued to be revered, with many being assimilated into the Roman religious system through a process known as syncretism. This blending of beliefs allowed for the worship of hybrid gods, combining attributes of Roman and native gods. For instance, the goddess Sulis was identified with Minerva at the famous Roman Baths in Bath, and Mars was equated with local war deities like Cocidius and Belatucadrus in the region of Hadrian’s Wall.

Mystery cults, originating from different corners of the empire, found their way to Britain and gained followers. These cults often centred around enigmatic deities and promised secret knowledge and personal salvation to their initiates. The cult of Mithras, for example, was particularly popular among Roman soldiers, offering a sense of brotherhood and the promise of life after death.

The reverence for local spirits or genii was another aspect of religious life in Roman Britain. Both Romans and Iron Age Britons believed in the presence of spirits in every person, place, and thing. Honouring these spirits was a common practice, and it was thought to bring protection and favour. This belief system facilitated the integration of Roman and local gods, as there was no fundamental clash between the two belief systems.

The persistence of pre-Roman Iron Age beliefs is also evident in the significance afforded to horned gods, sacred wells, and ritual shafts. The occurrence of gods in groups of three, such as the matres (mothers) and the genii cucullati (hooded deities), carved in stone at Housesteads on Hadrian’s Wall, reflects the continuation of native religious traditions alongside Roman practices.

In summary, the religious practices in Roman Britain were characterized by a remarkable degree of diversity and syncretism. Christianity coexisted with the worship of Roman gods, the Imperial Cult, local Celtic deities, mystery cults, and the veneration of spirits. This pluralistic religious environment was a result of the Roman policy of religious tolerance and the adaptability of religious beliefs to new cultural contexts.

The Roman approach to other beliefs

The Romans’ approach to the various religious practices in Britain was largely characterized by tolerance and syncretism. They had a pragmatic view of religion, seeing it to maintain the social order and unify the diverse peoples within their empire. This is evident in their willingness to incorporate local deities and practices into their own pantheon and religious life. The Romans did not seek to replace the existing religious beliefs, but rather to integrate them, allowing for a coexistence that facilitated the smooth governance of their provinces.

In Roman Britain, the Romans encountered a complex tapestry of religious beliefs, including those of the native Celtic population. Instead of imposing their own religious system, the Romans often equated their gods with local deities, a process known as interpretatio Romana. This practice allowed for the worship of hybrid gods, blending Roman and local attributes, which can be seen in the fusion of the goddess Sulis with Minerva at the Roman Baths in Bath.

The Imperial Cult, which involved the worship of the emperor, was another aspect of Roman religion that was introduced to Britain. While the Romans expected participation in this cult as a sign of loyalty to the empire, they did not enforce it to the extent that it overshadowed local religious practices. The Romans understood the importance of respecting local traditions to maintain peace and order.

The Romans also brought with them various mystery cults, such as those dedicated to Mithras and Isis, which were particularly popular among the military and the urban populations. These cults offered a more personal and mystical religious experience compared to the traditional civic religions of Rome and were allowed to flourish in Britain.

Furthermore, the Romans were known for their belief in numina, the spirits or divine forces believed to inhabit objects and places. This belief was compatible with the Celtic reverence for natural places and spirits, allowing for a harmonious blend of Roman and local religious practices.

The Romans’ religious tolerance is also reflected in their response to Christianity. Although initially suspicious of the new religion due to its exclusivity and refusal to participate in the Imperial Cult, the Romans eventually granted Christianity legal status with the Edict of Milan in AD 313. By the end of the fourth century, Christianity had become the official state religion of the Roman Empire, yet the Romans continued to allow the practice of other religions in Britain.

The Romans did not actively promote one singular religious practice; rather, they implemented a policy of religious tolerance that allowed for the coexistence of various beliefs and practices. However, they did encourage the worship of the Imperial Cult, which involved venerating the emperor as a divine figure. This practice was not only a religious act but also served as a demonstration of political loyalty and social cohesion within the empire. The Romans sought to integrate their gods with those of the local population, a process known as syncretism, which led to the worship of hybrid deities that combined Roman and Celtic attributes. This approach facilitated the smooth governance of their provinces and helped to maintain peace and order.

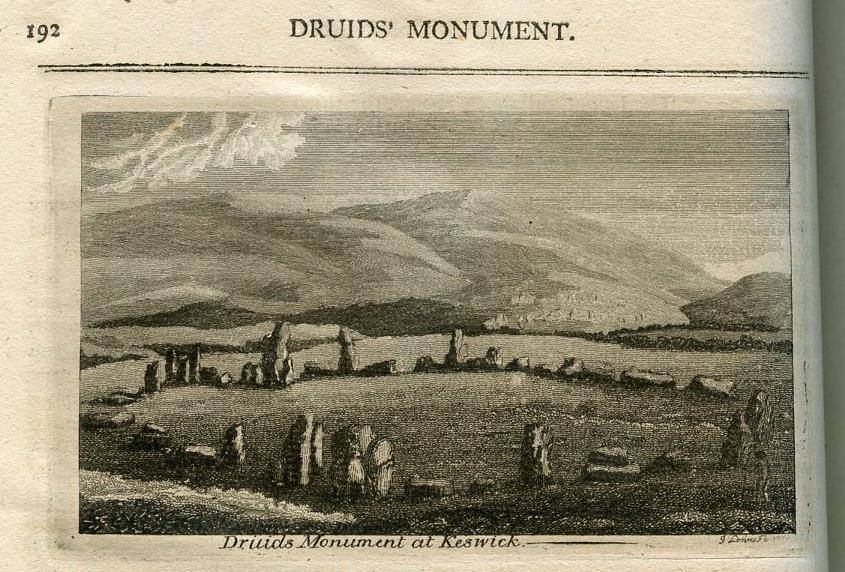

The oppression of the Druids

The suppression of the Druids during the Roman invasion of Britain is one notable exception to this general policy of tolerance. The Druids were seen as a unifying force among the Celtic tribes and a potential source of resistance against Roman rule. By suppressing the Druids, the Romans aimed to weaken the social and religious structures that could challenge their authority.

The suppression of Druids by the Romans had a significant impact on the religious life in Britain, marking a profound shift in the spiritual landscape. Druidism, which was deeply interwoven with Celtic society, served not only as a religion but also as a system of legal and scholarly practices. The Druids were the intellectual elite, presiding over religious ceremonies, education, and the legal system, and their suppression disrupted these traditional roles.

When the Romans initiated their campaign against the Druids, particularly with the massacre at Anglesey, which was a stronghold of Druidic culture, it symbolized a deliberate effort to dismantle the power structures that could oppose Roman rule. This act was not merely a military endeavour but also a strategic move to erode the social and religious cohesion that the Druids fostered among the Celtic tribes.

The decline of Druidism led to the gradual erosion of the traditional Celtic religious practices that the Druids had upheld. With the Druids’ influence waning, the Roman religious practices and deities gained prominence. The process of syncretism, where Roman gods were equated with Celtic ones, accelerated, leading to a religious amalgamation that reflected the Roman Empire’s cultural dominance.

The suppression also had the unintended consequence of paving the way for the spread of Christianity. As the old religious order collapsed, the new religion found fertile ground. The Christian Church, with its structured hierarchy, filled the void left by the Druids, eventually becoming the dominant religious force in Britain. This transition was facilitated by the Roman Empire’s eventual adoption of Christianity as the state religion, which further marginalized the remnants of Druidic practice.

Moreover, the suppression of the Druids contributed to the loss of cultural heritage. The Druids had been the custodians of oral tradition, and their decline meant that much of the knowledge they held was lost or became fragmented. This loss extended beyond religion to affect the broader cultural, historical, and linguistic heritage of the Celtic peoples.

In the long term, the suppression of the Druids led to a transformation of British religious life from a polytheistic and animistic tradition towards a predominantly Christian one. While the immediate impact was the diminishment of Druidic influence, the long-term effects included the integration of Roman and Christian practices with the remnants of Celtic tradition, creating a unique religious synthesis that would evolve over the centuries.

Despite this, the Romans largely allowed the continuation of local religious practices. They recognized the importance of respecting and incorporating local traditions to ensure the stability of their rule. This is evident in the way local gods were merged with Roman ones, and how the Romans accommodated the worship of Celtic deities alongside their own. For example, at Bath, the goddess Sulis was identified with Minerva, and in the Hadrian’s Wall area, the Roman god Mars was equated with local war gods like Cocidius and Belatucadrus.

The Romans also introduced a range of deities from outside the classical pantheon, reflecting their openness to foreign influences. The cults of Eastern gods such as Mithras and Isis found followers in Britain, particularly among the military and urban populations. These mystery cults offered a more personal and mystical religious experience compared to the traditional civic religions of Rome and were allowed to flourish in Britain.

Furthermore, the Romans’ belief in numina, the spirits or divine forces believed to inhabit objects and places, was compatible with the Celtic reverence for natural places and spirits. This belief system facilitated the integration of Roman and local religious practices, allowing for a harmonious blend of beliefs.

The Romans’ approach to religion in Britain was thus characterized by a combination of tolerance, adaptation, and strategic suppression. While they did not actively promote any particular religious practices, they did encourage the worship of the Imperial Cult and facilitated the syncretism of Roman and Celtic deities. This strategy helped to integrate the Roman and Celtic populations, ensuring the stability and cohesion of Roman Britain.

Christianity in Roman Britain

The advent of Christianity in Roman Britain is a subject of historical interest, reflecting a period where religious beliefs were both diverse and evolving. Christianity was indeed present in Roman Britain from at least the third century, coexisting with various other religious practices, including those of the native Celtic religion and the Roman pantheon. The term ‘syncretic’ aptly describes the blending of different religious traditions, and in the context of Roman Britain, it suggests a fusion of Christian tenets with local and Roman customs. This syncretism was likely a gradual process, influenced by the complex interplay of cultural exchange, political power, and individual belief systems.

Archaeological evidence for Christianity during this period, while not extensive, provides insight into the religious landscape of Roman Britain. Artifacts bearing potential Christian imagery, such as the Chi-Rho symbol, have been discovered, indicating the presence of Christian worship and iconography. Additionally, the existence of church structures and Christian burial traditions points to an organized and practising Christian community. Literary sources, including works by early Christian writers like Bede and Gildas, also reference the presence of Christianity in Britain, further corroborating the archaeological findings.

The religious milieu of Roman Britain was indeed syncretic, with Christianity being one of several eastern cults introduced to the province. The archaeological and literary evidence suggests that while Christianity was not the dominant religion, it was a significant and growing presence. This growth was likely bolstered by the Edict of Milan in AD 313, which recognized Christianity as a licit religion within the Roman Empire, and later by the Edict of Thessalonica in AD 380, which made it the state religion.

The syncretism of early British Christianity can be seen as a reflection of the broader Roman approach to religion, which often incorporated and adapted various beliefs and practices. This adaptability may have facilitated the acceptance and integration of Christian practices into the existing religious framework of Roman Britain. However, it is important to note that the degree of syncretism would have varied across different regions and social strata, with some communities possibly adhering more strictly to orthodox Christian practices, while others blended them with local traditions.

Christian Syncretism in Italy

The relationship between the Roman Catholic Church and the ancient Roman pantheon is complex and multifaceted. Syncretism, the blending of different religious beliefs and practices, was indeed a common feature in the Roman Empire, especially as it expanded and incorporated a multitude of cultures and deities. The early Church, emerging within this syncretic cultural milieu, faced the challenge of defining its identity and doctrines in a world where religious boundaries were often fluid.

While the Church itself did not formally adopt the Roman pantheon, the process of Christianization often involved the reinterpretation or recontextualization of pre-existing religious spaces, practices, and festivals. This can be seen in the transformation of pagan temples into Christian churches or the Christianization of pagan holidays.

For instance, the Pantheon, a temple originally dedicated to all the gods of Ancient Rome, was consecrated as a Christian church dedicated to St. Mary and the Martyrs. Such actions were part of a broader strategy to ease the transition for converts and to establish the dominance of Christianity within the Roman cultural and religious landscape. However, it is important to distinguish between the official stance of the Church and the syncretic practices that may have occurred locally as Christianity spread. The adaptation of local customs and traditions was sometimes a pragmatic approach to evangelization, but it did not necessarily reflect a doctrinal acceptance of the older deities.

Over time, the Church worked to clarify its teachings and to discourage syncretic practices that were at odds with its theology. The nuanced approach of the Church towards syncretism has been a subject of scholarly debate, with some arguing that certain aspects of Christian worship and iconography bear the influence of earlier pagan traditions, while others maintain that the Church maintained a clear doctrinal separation from pagan religions. The historical process of Christianization was undoubtedly complex, involving both deliberate and organic elements of cultural and religious exchange.

The Christianization of Italy, a process marked by both conflict and cultural exchange, offers several examples of syncretism where Christian and pagan practices were intertwined. One of the most emblematic cases is the Feast of the Annunciation, which coincides with the pagan celebration of the coming of spring, symbolizing new life and rebirth, themes that resonate with the Christian narrative of the Incarnation. Additionally, the cult of saints in Christianity often mirrored the veneration of local deities, with many saints becoming patrons of specific places, embodying attributes similar to those of the pre-Christian gods they replaced. The transformation of pagan temples into Christian churches is another example, with the Pantheon in Rome being one of the most famous instances, as it was rededicated to St. Mary and the Martyrs. This act of consecration served not only a religious purpose, but also a political one, asserting the dominance of the new faith over the old.

Moreover, the adaptation of the Roman calendar, with Christian holidays often falling on dates previously reserved for pagan festivities, facilitated a smoother transition for converts. For instance, Christmas was celebrated on December 25th, aligning closely with the Roman festival of Saturnalia, a time of feasting and goodwill. Similarly, the Christian All Saints’ Day followed the pagan festival of Lemuria, dedicated to appeasing the spirits of the dead. The practice of incorporating Christian elements into existing architectural structures can also be seen in the early Christian mosaics of Ravenna, which blend Roman artistic traditions with Christian iconography.

The lives of the early Christian martyrs, as recorded in hagiographies, often contain elements that reflect a syncretic mixture of Christian virtue and classical heroism. These texts served to inspire the faithful by drawing parallels between the martyrs’ sacrifices and the noble deaths of pagan heroes. The Christian doctrine itself was sometimes influenced by the philosophical ideas of the time, with theologians like Augustine of Hippo engaging with and reinterpreting Neoplatonism to explain Christian concepts.

In the realm of literature, Dante Alighieri’s “Divine Comedy” stands as a testament to the syncretic intellectual environment of medieval Italy, where Christian theology, classical mythology, and Dante’s own imaginative vision are interwoven to create a unique allegorical narrative. The work reflects the ongoing dialogue between the ancient and the medieval worlds, showcasing the enduring influence of classical culture on Italian thought and spirituality.

The process of Christianization in Italy was not a simple replacement of one religious system with another, but a complex negotiation between continuity and change. It involved the reinterpretation of old beliefs and practices within the framework of the new faith, often leading to a rich cultural synthesis that shaped the religious and social identity of Italy for centuries to come. This syncretism is a powerful reminder of the dynamic nature of cultural transformation and the ways in which religious traditions can evolve and adapt over time.

Christian syncretism in Greece

In Greece, the process of Christianization also involved syncretism, much like in Italy. The ancient Greeks had a long history of syncretizing their gods with those of other cultures, which set a precedent for later religious transformations. When Christianity spread to Greece, it encountered a rich tapestry of Hellenistic beliefs deeply rooted in the culture. One of the most prominent examples of syncretism in Greece is the integration of the worship of the Egyptian gods Isis and Serapis into the Greek pantheon. This blend of Egyptian and Greek religious practices became particularly popular during the Hellenistic period, following the conquests of Alexander the Great.

The cult of Serapis, a deity that combined aspects of Greek and Egyptian gods, is a striking instance of this syncretism. Serapis was associated with Zeus and Hades from the Greek pantheon and Osiris and Apis from the Egyptian pantheon, embodying attributes of both cultures. The worship of Serapis and Isis in Greece illustrates how the Greeks were open to incorporating foreign elements into their religious life, a trait that would later influence the Christianization process.

Moreover, the adaptation of Christian saints and narratives to local contexts often mirrored earlier Hellenistic practices. For example, many of the qualities of the Greek gods were transferred to Christian saints, who then took on roles similar to the deities they replaced. This is evident in the veneration of Saint Nicholas, who shares many attributes with the Greek god Poseidon, being revered as a protector of sailors and associated with the sea.

The transition of religious festivals from pagan to Christian observances is another aspect of syncretism. The celebration of Easter, for instance, coincides with the timing of the ancient Greek festival of Dionysia, which celebrated the god of wine and fertility, Dionysus. This alignment allowed for a smoother transition by reinterpreting existing celebrations within a Christian framework.

Architectural syncretism is also visible in Greece, where ancient temples were repurposed as Christian churches. This not only provided a physical space for Christian worship, but also symbolically represented the triumph of Christianity over paganism. The Church of Panagia Ekatontapiliani in Paros, for example, is said to have been founded by Saint Helen, the mother of Emperor Constantine, and stands on the site of a former ancient temple.

In literature and philosophy, the works of early Christian writers in Greece often reflect a syncretic approach, incorporating Hellenistic philosophical concepts into Christian theology. The Cappadocian Fathers, for instance, were influential in shaping Christian doctrine using the language and ideas of Greek philosophy.

Greek philosophers played a pivotal role in the shaping of early Christian thought, serving as both a foundation and a foil for the development of Christian theology. The intellectual milieu of the Greco-Roman world was rich with philosophical traditions such as Stoicism, Platonism, Epicureanism, and various sceptic schools, which provided a conceptual framework that early Christian thinkers could engage with and adapt. The New Testament itself records instances of this interaction, notably in Acts 17:18, where the Apostle Paul is described as discussing with Epicurean and Stoic philosophers.

The assimilation of Hellenistic philosophy into Christian thought was anticipated by Philo of Alexandria, a Hellenistic Jew who harmonized Jewish scriptural tradition with Stoic and Platonic philosophy. This syncretic approach influenced early Christian writers like Origen and Clement of Alexandria, who were educated in Greek philosophy and employed its concepts to articulate their Christian beliefs. Clement famously regarded Greek philosophy as a preparatory stage for the Christian faith, suggesting that it contained elements of the true knowledge revealed in Christianity.

The Christian church’s arrival in Ireland

The early Christian church’s arrival in Ireland marked a complex period of religious and cultural transformation. Syncretism, the blending of different religious and cultural influences, played a significant role in this process. As Christianity spread through Ireland from the 5th century onwards, it encountered a deeply entrenched Celtic paganism. This paganism was rich with its own pantheon of deities, rituals, and an Otherworldly mythology that had shaped Irish identity for centuries. The Christian missionaries, including figures like St. Patrick, faced the challenge of converting a population whose spiritual life was closely tied to the natural world and seasonal cycles.

The missionaries adopted a strategy of accommodation and integration rather than outright replacement of the old beliefs. They often built churches on sites that were sacred in the Celtic religion, co-opting the sanctity of these places for Christian worship. Christian saints were sometimes equated with Celtic gods, and Christian holidays were set to coincide with major Celtic festivals, such as Easter with the spring festival of Beltane. This strategic syncretism facilitated a smoother transition by allowing the Irish to retain a sense of continuity with their past while adopting new Christian practices.

The result was a unique form of Christianity that retained many elements of Celtic spirituality. This is evident in the Irish monastic tradition, which became renowned for its scholarship and piety. The monasteries served as centres of learning and preserved not only Christian texts but also the literature and oral traditions of the Celts. The hagiographies of Irish saints often contain elements that are reminiscent of Celtic mythology, suggesting a fusion of Christian and pre-Christian narratives.

The Book of Kells, an illuminated manuscript created by Celtic monks, exemplifies this syncretism through its intricate artwork that combines Christian iconography with Celtic motifs. The persistence of certain Celtic customs and beliefs within Irish Christianity is a testament to the syncretic process that occurred during the early medieval period. The synthesis of Christian and Celtic elements contributed to the rich tapestry of Irish cultural heritage and helped to create a distinctive Irish Christian identity that has endured to this day.

In scholarly research, this period of Irish history is often examined through comparative studies of the Celtic-Irish Otherworld and the Christian Otherworld, revealing a model of syncretism that preserved aspects of both European and Celtic culture. The conversion of Ireland to Christianity was not a swift or simple process but rather a gradual amalgamation of beliefs and practices over several centuries. This syncretism is a key aspect of the historical narrative, illustrating how the early Christian church in Ireland absorbed and transformed the older Irish Celtic pantheons into a new, distinctively Irish expression of Christianity.

The role of Saint Patrick

St. Patrick’s role in the syncretism of Christian and Celtic traditions in Ireland is a fascinating aspect of religious history. Known as the “Apostle of Ireland,” he is credited with spreading Christianity across the country in the 5th century. His approach to conversion was strategic and empathetic, recognizing the deep-rooted spiritual and cultural practices of the Irish people. Instead of attempting to eradicate the existing belief system, St. Patrick sought to integrate Christian teachings with Celtic traditions, facilitating a smoother and more acceptable transition for the local population.

St. Patrick’s methods included the adaptation of symbols and practices that were familiar to the Irish. For instance, he is said to have used the shamrock, a native Irish plant, to explain the concept of the Holy Trinity, thus connecting a symbol from the natural world with a fundamental Christian doctrine. This clever use of symbolism helped bridge the gap between the two belief systems and made the Christian teachings more relatable to the Irish populace.

Moreover, St. Patrick’s efforts to establish Christianity did not stop at mere conversion; he also focused on the education and training of clergy within Ireland. He founded several monasteries, which became centres of learning and Preservation of both Christian and Celtic knowledge. These institutions played a crucial role in the cultural and religious life of Ireland, producing well-educated monks who would continue the work of spreading Christianity while respecting the Celtic heritage.

The legacy of St. Patrick’s syncretic approach is evident in many aspects of Irish Christianity. The Celtic Church, while adhering to the core tenets of Christianity, developed distinct practices and had a unique organizational structure that differed from the Roman model. The Irish penitential system, monastic traditions, and the celebration of feast days are examples of this unique blend of Christian and Celtic practices.

St. Patrick’s success in fostering a syncretic religious culture in Ireland can be attributed to his respect for the existing beliefs and his willingness to find common ground. By elevating and transforming Celtic deities into Christian saints and aligning Christian celebrations with Celtic festivals, he ensured that the transition to Christianity did not feel like a loss of identity for the Irish people. This approach made Christianity more accessible and enriched it with the depth and richness of Celtic spirituality.

The impact of St. Patrick’s work is profound and long-lasting. The syncretism he promoted helped to create a distinctive form of Christianity that was deeply rooted in the Irish cultural context. It is a testament to the power of cultural sensitivity and adaptability in the face of significant religious and cultural shifts. St. Patrick’s role in the Christianization of Ireland remains a pivotal chapter in the history of the early Christian church and its interactions with indigenous cultures.

The incorporation of Celtic culture into Christianity

St. Patrick’s incorporation of Celtic culture into Christianity extended beyond the use of symbols and the adaptation of festivals. His approach was holistic, encompassing various elements of Celtic society, spirituality, and artistic expression. One of the most enduring contributions was the establishment of the Celtic Cross, which combined the Christian cross with the Celtic circle, symbolizing eternity. This fusion of imagery became a central emblem of Celtic Christianity and remains a distinctive feature of Irish heritage.

In the realm of spirituality, St. Patrick and other missionaries embraced the Celtic reverence for nature, which was deeply ingrained in the local cosmology. They did not dismiss the sacredness of wells, trees, and high places, but rather reinterpreted these sites within a Christian context. Many of these natural sites were consecrated as holy wells or associated with saints, thus preserving their significance while aligning them with Christian worship.

The monastic tradition that St. Patrick helped to foster was another significant aspect of this cultural synthesis. The Irish monasteries became renowned for a distinctive style of asceticism that had parallels with earlier Celtic practices. The concept of ‘green martyrdom’ involved withdrawing from society to live a life of penance and prayer, echoing the hermit tradition of the Celts. These monasteries also became centres of learning and artistry, blending Celtic artistic styles with Christian iconography, as seen in illuminated manuscripts like the Book of Kells.

St. Patrick’s influence is also evident in the legal and social systems of the time. He is credited with the ‘Senchus Mór,’ a codification of Irish laws that integrated Christian principles with traditional Brehon law. This legal synthesis ensured that Christian ethics were woven into the fabric of Irish society, influencing everything from property rights to the treatment of slaves.

Furthermore, St. Patrick’s hagiography, which includes the famous ‘Confessio’ and ‘Letter to Coroticus,’ reflects a narrative style that resonates with Celtic storytelling traditions. These texts blend the saint’s personal testimony with elements of Irish oral culture, creating a compelling narrative that facilitated the spread of Christian ideals.

The liturgical practices in the Celtic Church also bore the mark of St. Patrick’s syncretic efforts. The Celtic liturgy developed its own distinct rhythm, with prayers and rituals that reflected the Celtic sense of the divine in everyday life. The emphasis on penitential practices, the celebration of local saints, and the veneration of relics were all influenced by pre-Christian customs.

St. Patrick’s role in the syncretism of Celtic and Christian traditions was multifaceted. He was instrumental in creating a unique form of Christianity that was deeply Irish in character, yet firmly rooted in the universal Christian faith.

Persisting Celtic rituals

The intertwining of Celtic rituals with Christian practices in Ireland created a unique religious tapestry that has persisted through the ages. One of the most prominent examples of this syncretism is the festival of Samhain, which marked the end of the harvest season and the beginning of winter. This festival was seamlessly transformed into All Hallows’ Eve, now known as Halloween, blending the Christian tradition of honouring saints and martyrs with the Celtic celebration of the otherworldly and the end of the year.

Another ritual that found its way into Irish Christianity was the reverence for holy wells. In Celtic times, these wells were believed to be portals to the otherworld and were often the sites of healing and divination. The Christian church rededicated these wells to saints, and they became places of pilgrimage, where people would still come to seek healing and leave offerings, much like their ancestors did.

The Celtic practice of erecting standing stones and high crosses also continued under Christianity. These crosses, which combined the Christian symbol with Celtic art, often marked places of worship or were used as territorial markers, just as standing stones had been used previously. The high crosses remain a distinctive feature of the Irish landscape and a symbol of the syncretic nature of Irish Christianity.

The tradition of the ceilidh, a social gathering that often included storytelling, MUSIC, and dance, was another cultural element that persisted. While the content of the stories and songs shifted to reflect Christian morals and narratives, the communal aspect of sharing and celebrating together remained a vital part of Irish life.

The monastic tonsure, a distinctive hairstyle worn by monks, is another example of a Celtic practice adopted by the Christian church. While the Roman church shaved the top of the head, the Celtic tonsure involved shaving the front of the head from ear to ear, which was a style associated with Druids and warriors in pre-Christian Ireland.

The concept of penance in Irish Christianity also has roots in Celtic customs. The Celtic system of penance was unique in its emphasis on restitution and reconciliation, rather than just contrition and confession. This system was integrated into the Christian practice of confession, which became a central part of spiritual life in Ireland.

Lastly, the popularity of going into “exile for Christ,” where individuals would leave their homes to live as hermits or pilgrims, echoes the Celtic tradition of self-imposed exile for spiritual enlightenment. This practice was seen as a form of martyrdom, a way to share in Christ’s suffering, and was highly regarded in the Celtic Christian tradition.

Celtic deities as saints

The intertwining of Irish Celtic deities with Christian saints is a nuanced aspect of Ireland’s religious history. While it is not common for churches to be named directly after Celtic deities, there was a tendency to revere local figures who may have had connections to pre-Christian traditions and later became recognized as saints within the Christian church. The process of Christianization often involved the transformation of local heroes, leaders, or revered figures into saints, and this sometimes included those who may have been associated with older deities or spiritual entities.

In the context of Irish Christianity, many of the saints venerated had strong ties to the communities where they preached, and over time, their legends and the respect they commanded absorbed elements of the local pre-Christian culture. This is reflected in the hagiographies of Irish saints, which often contain miraculous events and stories that echo the mythological tales of the Celtic gods and heroes.

One of the most prominent examples is St. Brigid of Kildare, who shares many attributes with the Celtic goddess Brigid, known for her association with healing, poetry, and smithcraft. The goddess Brigid was a member of the Tuatha Dé Danann, a group of divine beings in Irish mythology, and was revered as a protector of livestock and a guardian of the home. As Christianity spread, the figure of St. Brigid emerged, carrying over many of the goddess’s qualities and becoming one of Ireland’s most venerated saints, with numerous churches and holy wells dedicated to her.

Another figure of note is St. Columba, also known as Colum Cille, whose name means ‘Dove of the Church.’ He is often associated with the Celtic deity Lugh, a god of light and skill. While the connection is less direct than that of St. Brigid, the attributes of wisdom, leadership, and artistic skill attributed to St. Columba echo those of the god Lugh, suggesting a subtle syncretism at play. St. Columba’s establishment of monasteries and his role in spreading Christianity in Scotland further cemented his status as a pivotal figure in the Christianization of the Celtic world.

St. Patrick himself, while not directly linked to a specific Celtic deity, played a significant role in the syncretic process by incorporating elements of Celtic spirituality into his teachings. His use of the shamrock to explain the Holy Trinity is a well-known example of this synthesis. The shamrock, a common plant in Ireland, was imbued with new meaning as it came to represent an important Christian concept, thus bridging the gap between the old and the new beliefs.

The figure of St. Kevin of Glendalough is another example where pre-Christian elements are woven into the narrative of a Christian saint. St. Kevin is celebrated for his harmony with nature, living as a hermit and forming close bonds with animals. This echoes the Celtic reverence for the natural world and suggests a continuity of the animistic world-view within the Christian context.

In addition to these, there are numerous lesser-known saints whose cults may reflect syncretic origins. Saints such as St. Gobnait, associated with bees and healing, and St. Dymphna, linked with mental health, carry forward the Celtic tradition of specialized deities overseeing particular aspects of life and nature. Their stories and the rituals associated with their veneration often contain echoes of pre-Christian beliefs and practices.

It is important to recognize that while the evidence of syncretism is compelling, the process was likely organic and multifaceted, involving a gradual blending of traditions over time. The saints’ lives, as recorded in hagiographies, were often written centuries after their deaths, and thus, they reflect the evolving understanding of these figures within a Christian framework that had already absorbed many Celtic elements.

The legacy of these syncretic saints is still evident in modern Ireland, where the intertwining of Christian and Celtic traditions continues to shape religious and cultural identity. The veneration of saints with connections to Celtic deities represents a fascinating chapter in the history of Irish Christianity, illustrating the enduring influence of Celtic spirituality and the adaptability of religious practices in the face of cultural change.

The naming of churches after saints in Ireland was a way to establish a Christian presence in areas that held significance in the Celtic belief system. By dedicating these sites to Christian saints, the church could provide continuity with the past while steering the spiritual focus towards the new faith. This practice helped to ease the transition for the local population, who could still visit and hold in esteem these traditional sites, now under the auspices of Christianity.

Moreover, the Irish tradition of naming children after saints, which often extended to the naming of churches, served to reinforce the Christian faith and create a sense of continuity with past generations. This practice ensured that many church names were connected to the church, often reflecting the community’s hope for their collective spiritual life. In this way, the names of churches often became intertwined with the legacy of saints who, in turn, were sometimes linked to the attributes of Celtic deities.

It is important to note that the process of recognizing saints in the early Christian church was less formalized than it is today. Local veneration of saints was common, and many saints were canonized by popular acclaim rather than official declaration. This allowed for a greater blending of local traditions with Christian practices, including the naming of churches after these locally venerated figures.

While it is not accurate to say that many Irish church names directly reflect Celtic deities, there is a complex layer of cultural and religious syncretism where the attributes, legends, and respect for certain Celtic figures were absorbed into the veneration of Christian saints. This syncretism is evident in the names and dedications of churches, which often served as a bridge between the old beliefs and the new Christian faith, reflecting a deep and enduring connection to Ireland’s Celtic heritage.

Conclusion

What is means is that many Christian churches in Brigantia may well be sited exactly where those earlier temples and places of pagan belief were centred, and the imagery found in those churches may well reflect aspects of pagan belief from earlier periods. From my research so far, it’s fairly safe to assume that most churches that existed at the time of the Norman Conquest, were built on Roman temples, which were located on pre-existing sites of Celtic reverence.

Courtesy of archaeology.com

Courtesy of archaeology.com