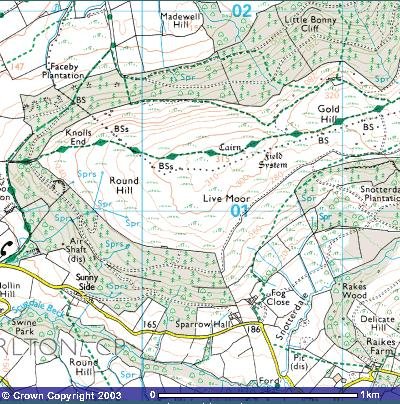

Directions. 0/S 1:50,000 series map 103 ref. 885384. Leave Nelson on the A6068 towards Colne, and turn right after passing under the railway bridge at Colne station. Follow this out of the town, up the steep hill until the gradient eases, and the hillfort is on the right at a sharpish left hand bend, by a junction. Park here, and a footpath leads from the bend to the hillfort.

District: Pendle Name : Castercliff Camp, Nelson. Description: Iron Age hillfort with hut circles, but somewhat scarred by mining. Castercliff is a small Multivallate hillfort of Iron Age date. It is located on an eminence overlooking the Calder Valley and includes an oval-shaped internal plateau measuring approximately 115m by 76m that is enclosed on all sides except the north by three rubble ramparts, each up to 1.5m high and situated on the slope of the hill, with an external ditch up to 1.5m deep in front of each. The maximum width of the whole rampart and ditch system is approximately 46m. On the north side the defences are incomplete and consist in the main of a single rampart and ditch. However, some short lengths of triple rampart and ditch separated by areas of undisturbed ground are also visible here. Limited excavation of the defences indicated that the inner rampart was revetted with stone and also timber-laced. SD: 88480,38390

Plan of Castercliff

"Lancashire, too, has few hillforts, six in fact, none of which are of any great size. Castercliff is the county's best example but, if truth be told, there are many other hillforts omitted from this gazetteer, especially in the South and West, to make room for a Palatine presence. That said, Castercliff is not without its merits, although first impressions are of a circular pile of rubble.

That in itself makes a change from the grass-clothed ruins of most hillforts, while Castercliff has an unusual appearance. On the inside, a low bank forms an inner circle, which now is only about one foot high. This was the original rubble filled, wooden-laced, stone-faced rampart. Unusually, there does not appear to have been a ditch, while entry was gained in the west. A number of excavations have been undertaken on this two acre site, in 1958, 1960 and 1970-71, and it is thought that this rampart had been 'vitrified', either by design, accident or attack. This is unusual for England, but there are a significant number of vitrified hillforts in Scotland, i.e. the rampart's internal timbers have been set on fire, by any of the three aforementioned methods, to weld, or 'vitrify' the stones together. Immediately beyond the original rampart is the second timber revetted, box rampart, with a ditch up to ten feet deep in places, and a counterscarp bank to the south. This rampart is in a series of short lengths in the north, and the excavations have shown that the flat land between has not been built on. Castercliff was thus abandoned before its rebuilding was completed, and the excavators came across no finds of significance, which begs the question of it ever being permanently occupied. The entrance to the later hillfort also appears to have been in the west, while it might have been intended to have one in the east as well. It was thought that Castercliff was built in the first century B.C., but good old Carbon-14 dating of charcoal has revised that somewhat, and it was probably constructed in either the sixth or seventh centuries B.C. Castercliff stands on a surprising 930 feet high plateau, in the foothills of The Pennines. Although the hills rise to a considerable height to the east, they are not overpowering, while the hillfort was well situated in terms of over-seeing the land to the north, south and west, in particular the river valley." The Iron Age Hill Forts of England, 1993 - Geoffrey Williams.

Description Castercliff Camp is a small oval Iron Age multivallate "Vitrified" hillfort (enclosing c.2 acres). It has been suggested that the hillfort was built in two stages, the second of which was not completed. Forde-Johnson states: "The original defences appear to have consisted of a single bank without a ditch, with a bank and ditch between, and in places, a counter Scarp bank added later. On the northern side of the site, however, these additional defences appear to have been unfinished. Instead of a continuous bank and ditch, there are a series of short lengths with level ground between them, that shows no sign of having been disturbed." This was corroborated in 1971 by Coombs, who excavated the central rampart and found in between two of the rampart sections an area of undisturbed ground. The excavation also revealed continuous bedding trenches front and rear, 6 feet apart, in which were set chocked post holes up to 3 feet deep and about 6 feet apart.

The rubble core, 5 feet in height, survives and the bowed outline of revetting was visible in the excavated sections. Beyond the rampart was a rock cut ditch 5 feet deep and 6 feet wide at the mouth, with a probable counter scarp bank. The inner rampart was much denuded, due to the removal of large quantities of stones in the 19th century, it consists of a "low rubble and timber deposit very heavily vitrified", which probably constituted a stone revetted timber laced rampart. Roman coins have occasionally been found beneath the hill, but also more surprisingly, an iron cannonball, weighing six pounds, was also found. {4}{5}{6}{7}{8}{9}{10} There are many mining works and bell pits on the hill. {11} The air photos also reveal very faint traces of two circular or sub-circular platforms at SD 88383809 and SD 88453811. {12}

"This denuded hillfort is oval and encloses almost two acres. The defences comprise triple circuits of bank and ditch, with scarps representing outworks to the NE. The innermost bank is the slightest and may represent an earlier, univallate fort. It is complete, but shows only as a scarp or a very low bank. The middle ditch and bank are the stoutest, rising 3-5ft. Above the interior and falling 9 ft. to the present ditch floor. There are many gaps in it. The outer bank is the counterscarp to the central rampart and is discontinuous, but is well-preserved along the S and E sides. Outworks, which show as scarps, with short isolated lengths of bank, can be seen around the E and NE sides, about 70ft. Beyond the main defences.

The interrupted middle earthwork suggests that this, the second phase of the hill-fort, was never finished. Not dated." Guide to Prehistoric England, Nicholas Thomas. 1960.

Sources - from the SMR record

Ref no. {1} Type Map Colln. CLAU Year 1960 Title OS geol surv Clitheroe sheet 68 solid 1:63,360

Ref no. {2} Type Map Colln. CLAU Year 1975 Title OS geol surv Clitheroe sheet 68 Drift 1:50,000

Ref no. {3} Type Map Colln. CLAU Year 1970 Title OS Soil surv Lancs 1:250,000

Ref no. {4} Type Desc text Colln. - Author Forde-Johnson, J. Year 1976 Title Hillforts of the Iron Age in England and Wales, Vol. p. no. pp.101,106,122

Ref no. {5} Type Desc text Colln. UL Author Thomas-Watkins, W. Year 1883 Title Roman Lancashire Vol. p. no. p.199

Ref no. {6} Type Desc text Colln. UL Author Wilkinson, T. Year 1856 Title - Vol. p. no. TLCAS Vol.9, p.32

Ref no. {7} Type Desc text Colln. - Author Harrison, W Year 1896 Title Arch Survey of Lancs Vol. p. no. p.8

{8} Desc text UL Whitaker, T. 1801 History of Whalley Book 1 pp.26-7

{9} Desc text UL Brownbill, J., Farrer, W., EDS 1908 VCH Lancashire Vol.2 pp.514-5

{10} Desc text - Challis, A.J., Harding, D.W. 1975 Later Prehistory from the Trent to the Tyne British Archaeological Report 20 p.106 - Located

{11} Pers comm - Leech, P., FMW. 1982 -

{12} Pers comm CLAU Olivier, A.C.H., CLAU 1979 - {13} Excavation of the hillfort of Castercliff, Nelson, Lancashire, 1970-71 Trans. Lancs. & Ches. Antiq. Soc. 81, 111-30.

Castercliff Hillfort, Nelson, Lancashire – present state of knowledge

| Attribute | Evidence & interpretation |

|---|---|

| Topographic setting | Occupies the summit of Castercliffe Hill (280 m OD), a sandstone spur overlooking the confluence of the River Calder and Pendle Water. The fort commands two prehistoric east-west corridors: the Aire Gap (Craven to Wharfedale) and the Cliviger valley (Calder to Huddersfield). (Lancashire Past) |

| Earthworks | An oval plateau c. 115 m × 76 m is ringed on three sides by three stone-rubble ramparts with rock-cut ditches; the northern side has one, expanding to a triple system where the slope is easiest. Rampart/ditch package is up to 46 m wide; inner wall originally timber-laced and revetted. Maximum surviving bank height 1.5 m, ditch depth 1.5 m. (Historic England) |

| Excavation & dating | 1960–71: D. G. Coombs opened sections through all three ramparts. Burnt beam-sockets, oak charcoal and a radiocarbon determination of 510 ± 70 BC (Birm-123) place construction in the early to middle Iron Age. No occupation floors, post-holes or hearths were found inside the circuit, leading Coombs to conclude the fort was never finished or occupied. (A Corner of Tenth-Century Europe) |

| Finds | Hand-made coarseware body sherds, a Shale ring fragment and stray Roman coins from 19th--century digging on the south slope; the latter are thought to be chance losses rather than proof of Roman re-use. Bell-pits for 18th-century coal extraction have disturbed the interior strata. (The Journal Of Antiquities) |

| Later disturbance | Scores of shallow bell-pits and hush-gulleys attest to post-medieval coal and ironstone winning; these cut through inner rampart tumble and obscure any floor levels. Several 20th-century reservoirs and service trenches cross the north-east corner. The fort was fenced and scrub-cleared in 2006–08 under a Countryside Stewardship agreement. |

| Current status | Scheduled Monument “Castercliff small multivallate hill-fort” (List 1007404). Visibility good on west and south scarps; east side partly levelled by mid-19th-century quarrying. The site is public open land managed by Pendle Borough Council. (Historic England) |

Outstanding questions

- Function: The lack of internal buildings may indicate an incomplete stronghold or a short-lived communal work that was never occupied. Alternatively, light timber round-houses may have left only negative beam-slots, now masked by later coal pits.

- Regional role: Castercliff sits midway between the Pennine hill-fort chain to the south (Almondbury, Castle Hill) and Ingleborough to the north, hinting at a South Pennine frontier zone that has seen little systematic Iron-Age investigation.

- Environmental context: No palaeoenvironmental cores have been taken on the adjacent saddle bogs; pollen and microscopic charcoal would test whether large-scale woodland clearance accompanied rampart building.

- Chronological refinement: Coombs’ single radiocarbon date places construction broadly in the 6th–5th centuries BC, but no dates exist for later activity or palisade replacement. OSL or AMS dating of ditch-silts could verify whether some phases belong to the Late Iron Age.

Significance

Castercliff remains the largest and best-preserved prehistoric enclosure in Lancashire, yet, paradoxically, also one of the least understood: a three-bank hill-fort apparently deserted before completion, later pock-marked by coal mining and folklore linking it to Romans and medieval battles. Its rampart architecture places it firmly within the northern “small multivallate” tradition, but the absence of occupation debris contrasts sharply with contemporaries such as Almondbury and Ingleborough. Resolving whether Castercliff was an unfinished communal project, a seasonal livestock corral, or a fort whose timber buildings were erased by later industry will require renewed trenching targeted away from bell-pit disturbance and integrated environmental sampling across the hill-spur. Key sources: Coombs 1971 interim excavation report; Scheduled Monument description (Historic England); Northern Antiquarian and Lockdown Antiquarian field syntheses.Is Castercliff vitrified?

Yes – but only in patches, and the phenomenon has never been investigated to Scottish analytical standards.| Evidence | What it shows |

|---|---|

| Excavation notes (Coombs 1958-60; 1970-71) recorded “fused and glass-coated Gritstone along the inner revetment” and beams reduced to charcoal, implying a timber-laced wall that burned at very high temperatures. | The fused material is limited to the innermost rampart; the outer two earthworks are unaffected. |

| Historic-England/Heritage-Gateway record lists Castercliff as a “small multivallate vitrified hill-fort” – one of only three English examples (others: Almondbury, Wincobank). (Heritage Gateway) | Official scheduling accepts vitrification, although the extent is classified as “localised”. |

| Field reports & photography (e.g. Lock-down Antiquarianism blog, 2023) show green-black, vesicular stone still embedded in the collapsed inner bank. (A Corner of Tenth-Century Europe) | |

| 19th- and early-20th-century antiquarian descriptions also mention “slag-like masses” picked from the rampart tumble. (Flickr) |

Research done (and not done)

- 1960–71 excavations cut six trenches through the inner and middle defences. The campaign produced a single radiocarbon date (510 ± 70 BC) and confirmed timber lacing, but vitrified samples were neither chemically analysed nor archived.

- Later projects have focused on stabilising vandalism scars and mapping post-medieval bell-pits; none has re-opened the vitrification question.

Open questions

- Function – was the burning accidental (attack) or deliberate (ritual closure)? Lack of weaponry, plus the selective fusion of the inner wall, hints at an internal conflagration rather than siege.

- Extent – only scattered blocks are glassy; a full wall-core survey with portable XRF and micro-drilling could map heat gradients.

- Comparison – Almondbury (Castle Hill) and Wincobank show similar partial vitrification. A shared Pennine practice or three isolated events? No compositional work has yet compared their glasses.

- Chronology of burning – the single Iron-Age ^14C date could relate to construction timber, not the firing episode. AMS dates on charcoal still fused into the glassy matrix would pin down the burn event itself.

Next-step research possibilities

- Sampling campaign: extract 5–10 vitrified blocks for thin-section, SEM-EDS and lead-isotope assay; compare to local Pendle Grit bedrock.

- Magnetic susceptibility scan along the inner rampart to identify unexposed fused zones.

- Targeted OSL dating of ditch silt underlying fused tumble to fix a terminus post quem for the fire.

- Comparative study with Almondbury & Wincobank glasses to test for a Pennine “vitrification horizon” distinct from the better-known Scottish group.

Bottom line: Castercliff is almost certainly one of England’s very rare vitrified forts, but the phenomenon is documented only by eye and in passing. A small programme of modern materials science and dating could turn those anecdotal observations into hard data and plug an English gap in the wider study of British vitrified hill-forts.