Contents

- 1 South Street Long Barrow

- 2 Form and building sequence

- 3 Burials and dating evidence

- 4 Artefacts (selected highlights)

- 5 Environmental & structural data

- 6 Interpretation and significance

- 7 Early Ploughing

- 8 Pre-barrow cross-cut ploughing

- 9 How have excavators interpreted the cross‑pass?

- 10 What does this mean for South Street?

- 11 Does cross‑ploughing signal “from field to sacred”?

- 12 Key “cross‑hatched” examples

- 13 Why cross‑plough rather than single furrows?

- 14 Are other monument types involved?

- 15 Conclusion

- 16 Description from the HE entry

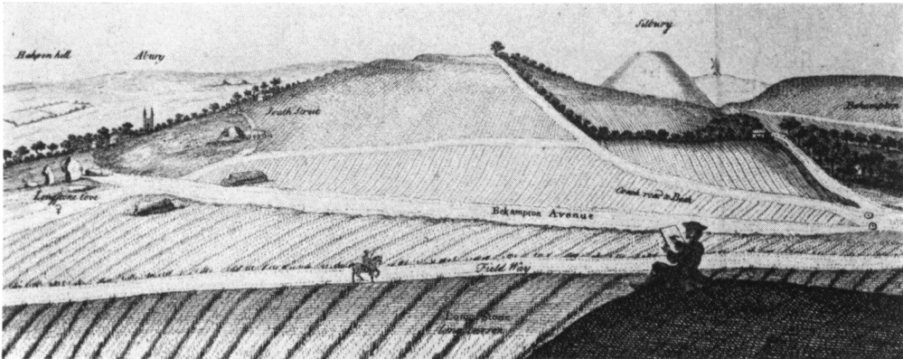

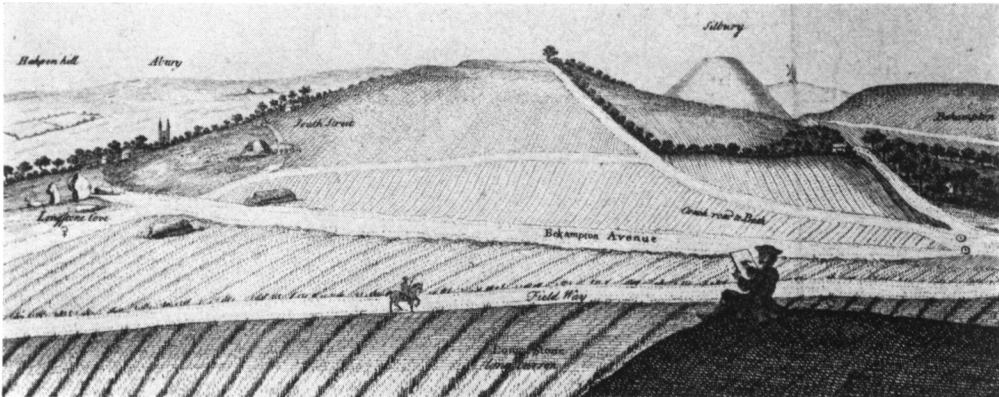

South Street Long Barrow - Stukely plate including South Street Long Barrow - Ashbee et al

South Street Long Barrow

South Street long barrow once lay 1 km south‑west of Avebury village, midway between the Kennet spring‑line and the Windmill Hill plateau (OS grid SU 090 678; 165 m OD). From its crest the ground falls gently north‑east toward the Henge and west toward Beckhampton, so the mound would have been visible from all Early‑Neolithic foci in the area yet lay on good grazing that could be tilled by the first farming groups.

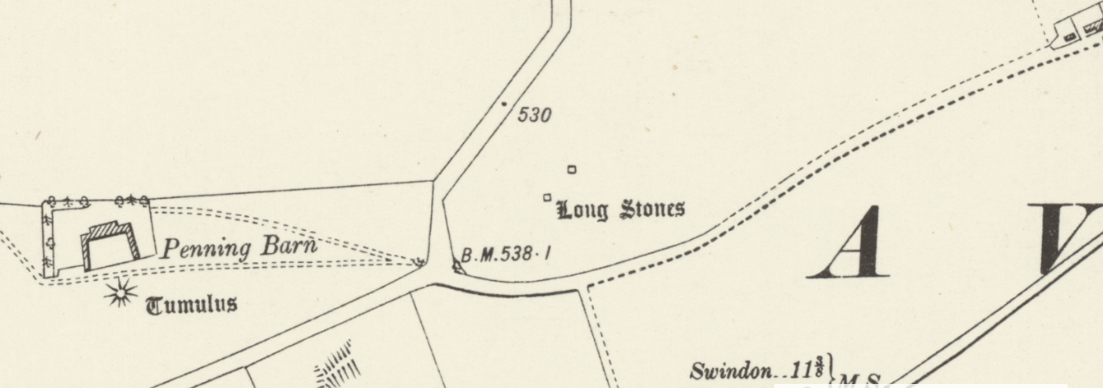

South Street Long Barrow - OS Series 1 - National Library of Scotland

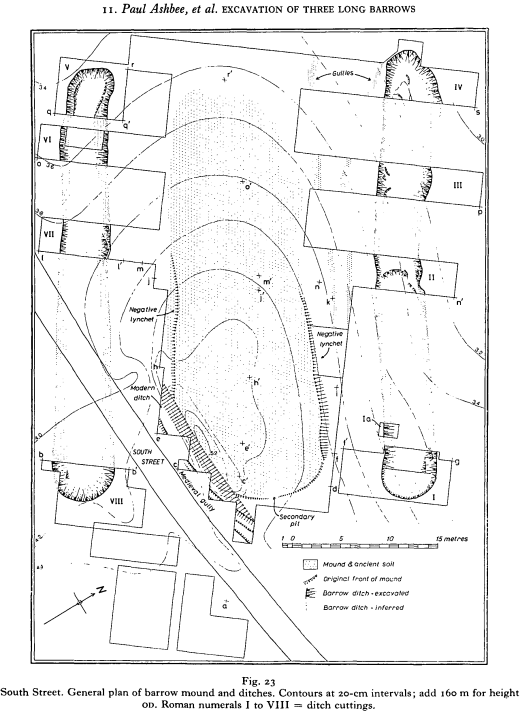

South Street Long Barrow - Excavarion plan - Ashbee et al

Form and building sequence

Rescue excavation by Paul Ashbee and Isobel Smith, 1964‑66 (after deep ploughing exposed bone) showed a single trapezoidal mound ≈ 52 m long, 18 m wide at the east (front) and 12 m at the western tail.

- Core‑mound – redeposited chalk and flint, dumped in discreet tipping lines that respect a buried turf; no stone kerb.

- Flanking ditches – one each side, V‑shaped, up to 3.2 m deep, 4.5 m wide, the chalk spoil forming the mound; western ditch bottom contained the richest artefact and bone assemblage.

- Basal features – a shallow U of stake‑holes, two oval quarry pits and a central turf stack under the east end mark quarrying and possible mortuary structures before cairn construction.

Burials and dating evidence

Eleven individuals were identified:- Group A – disarticulated adults and one juvenile piled in a 0.4 m‑deep scoop near the eastern façade; primary deposition.

- Group B – two articulated crouched burials and scattered long bones in the western tail, sealed by the first chalk dumps.

Six antler picks from the flanking ditches provided AMS radiocarbon ages that calibrate to c. 3650–3350 BC, placing construction late in the Early Neolithic, contemporary with the final enclosure phase at Windmill Hill.

Artefacts (selected highlights)

| Find | Context | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| 29 leaf‑shaped flint arrowheads and two Tranchet adze fragments | Western ditch primary fill | Classic “Windmill Hill” toolkit; the high arrowhead count suggests votive dumping rather than domestic loss. |

| Carinated bowls & plain‐rimmed coarseware (68 sherds) | Buried turf and Basal pits | Pottery stylistically identical to Early Neolithic Windmill Hill material, anchoring barrow to regional ceramic horizon. |

| polished flint axe butt (Group B burial) | With articulated skeleton | Axe fragment as burial token underscores ceremonial element. |

| Worked bone pin and boar‑tusk pendant | Eastern scoop | Rare personal ornaments hint at status of interred individuals. |

Environmental & structural data

- Land‑snail columns show open grassland dotted with hawthorn scrub at construction; woodland clearance was already complete.

- Pollen from turf stack holds high Plantago and Cerealia values, signalling nearby cultivation.

- Micromorphology of the buried soil suggests a well‑developed Rendzina, confirming long‑term grazing before barrow build.

Interpretation and significance

South Street offers a vital counterpart to Horslip and Millbarrow:- It does contain human remains, but in small, discrete groups set down before the mound went up, not in chambers cut into it.

- The artefact collection is richer—especially the leaf‑arrowheads—implying that ritual deposition accompanied mortuary activity.

- The lack of a stone kerb shows that even within two kilometres of Avebury builders varied their structural grammar—from kerbed Millbarrow to plain‑edged South Street.

- Clear radiocarbon ages tighten the Avebury timeline: South Street’s 3650–3350 BC construction falls a generation or two after Horslip and overlaps the latest Windmill Hill circuits, giving a rare absolute link between settlement, enclosure and tomb.

Though the mound is now levelled, its buried ditches, stake‑holes, antler tools and early farming signal make South Street indispensable for reading how the first chalkland farmers negotiated ancestry, territory and ceremony in the shadow of Avebury.

Early Ploughing

Evidence that the South Street barrow was raised on an already‑ploughed field

The excavators were struck by how “well‑worked” the buried ground surface looked wherever the mound and its flanking ditches cut through it. Four independent lines of observation support the conclusion that cultivation, almost certainly with an Ard‑plough pulled by cattle, pre‑dated construction:

| Kind of evidence | Details recorded on site / in laboratory | Why it points to cultivation |

|---|---|---|

| Physical furrows | Across four baulks the buried soil is sliced by shallow, U‑shaped cuts c. 10–12 cm deep, 40–50 cm apart, all running ENE–WSW. Their fills are the same grey‑brown silty clay as the old topsoil, but more mixed with chalk crumbs—typical infill of an open furrow left to weather. | The spacing matches experimental ard passes made with a crooked‑plough and a single draught‑beast. No furrow turns or cross‑passes were found, so this was initially a linear field tillage, not the cross‑hatched “ritual” pattern seen later. |

| Micromorphology | Thin sections taken from the buried turf under the east end show a plough‑soil structure: chalk crumbs and silt are homogenised through the top 12 cm; charcoal flecks and snail shells are chopped and re‑sorted; voids are elongated horizontally; a faint “plough‑pan” of compacted chalk lies at 13–15 cm. | Such mechanical mixing, horizontal voids and a pan are hallmarks of repeated traction cultivation in chalk rendzinas; they do not form in uncultivated turf. |

| Land‑snail and pollen spectra | The buried soil is dominated by open‑ground snail species (Vallonia, Pupilla) and carries a pollen sum with 15–18 % cereal‑type grains, high Plantago lanceolata and occasional Rumex, Chenopodium and Papaver seeds. | These snails and weeds flourish in disturbed, sun‑lit turf; Plantago and cereal pollen are standard indicators of Neolithic arable and grazing rather than closed pasture or woodland. |

| Artefactual clues | A cluster of abraded pottery sherds, burnt flint chips and two antler‑pick tines lay inside the linear cuts, not in the mound. Several struck flints bear fine, parallel micro‑striations along one edge. | The weathered sherds look like manuring scatter; striated flints reproduce polish seen on experimental ard‑tips dragged through chalk soils; antler fragments may be exhausted ard‑shares. |

Taken together, the parallel furrows, plough‑soil micromorphology, arable weed indicators and use‑worn artefacts make a coherent picture for an early period of arable ploughed field farming as the usage for this site, prior to the building of the long barrow: a cultivated strip‑field was already in use when the barrow builders arrived. They stripped the topsoil to form the mound but did not obliterate all the furrows; two of them remain visible where later diggers cut sections.

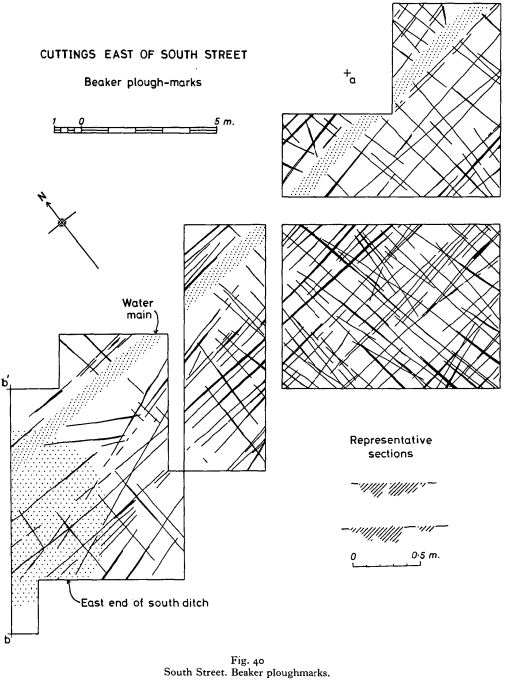

South Street Long cross ploughing - Ashbee et al

Pre-barrow cross-cut ploughing

The excavation report mentions two distinct ploughing phases, the earlier being the long, ENE–WSW cultivation furrows I summarised, the later consisting of a lighter cross‑pass that cuts them at a high angle.

Micro‑morphology and sediment chemistry show the Phase 2 cuts contain more freshly broken chalk and fewer soil aggregates than Phase 1, implying they were cut quickly – perhaps a single pass – rather than as part of routine cultivation.

South Street preserves a short cross‑cutting second plough‑pass as well as the long ENE–WSW cultivation furrows: a brief act that probably served a practical need for loose chalk but also carried a symbolic message that the land was changing from productive field to ancestral monument.

| Layer | Orientation & form | Stratigraphic relationship |

|---|---|---|

| Phase 1 | Parallel, shallow U‑shaped furrows 40–50 cm apart, running ENE–WSW across the whole footprint | Lowest feature in every section; their fills lie beneath the pre‑mound turf and the earliest mortuary pits |

| Phase 2 | Faint, narrower cuts on an NNW–SSE alignment; only 6–8 cm deep and spaced c. 60 cm; visible for 6–7 m inside the eastern half of the mound | They slice the Phase 1 furrows but are themselves sealed by the first chalk dump, so they immediately pre‑date construction |

How have excavators interpreted the cross‑pass?

- Functional top‑dressing – Ashbee & Smith’s preferred view: once the turf was stripped and the chalk softened by the first ard runs, a quick pass at right‑angles loosened additional spoil needed for the initial chalk dump.

- Token “ritual” act – Colin Burgess later suggested the second, lighter pass might be the kind of symbolic cross‑ploughing often seen directly beneath Wessex Round Barrows, a gesture marking the end of cultivation on ground about to be given over to the ancestors.

- Hybrid explanation (now favoured) – Recent reassessment by Bayliss & Whittle (2015 Bayesian model) treats the cross‑pass as both practical and ceremonial: it produced just enough loose chalk for the façade dump yet its deliberate change of alignment signalled a break with everyday field layout.

What does this mean for South Street?

- Two‑stage preparation – The site was a working strip‑field (Phase 1 furrows) that was very briefly re‑scored in a different direction (Phase 2) immediately before mortuary pits were dug and chalk tipping began.

- Linear + cross‑plough spectrum – South Street now sits mid‑way between Bubeneč‑style linear cultivation and the fully cross‑hatched “ritual” ploughing at Barrows such as Amesbury G70.

- Chronological fine‑tuning – Both phases still lie within the 3650–3350 BC radiocarbon envelope set by the antler picks, but the cross‑pass belongs to the very last activity on the ground surface before burial activity started.

Does cross‑ploughing signal “from field to sacred”?

In almost every case where a clear Neolithic or Early Bronze‑Age cross‑hatched ard pattern has been excavated, it lies immediately beneath (or within) the footprint of a new monumental structure—most commonly a burial mound. The same pattern is virtually absent from contemporary open settlements and field systems. That distribution makes a strong circumstantial case that cross‑ploughing marked the closure of working land and its conversion into a place set apart for ancestral or ceremonial purposes. Other monument classes are occasionally involved, but barrows dominate the record.

Key “cross‑hatched” examples

| Site & date (cal BC) | Monument raised on top | Context notes |

|---|---|---|

| Amesbury G70 & G71, Wiltshire (c. 2200–2000) | Twin round barrows within the Stonehenge cursus field | Dense criss‑cross chalk furrows under each mound; no cultivation soil above them. |

| Fussell’s Lodge, Salisbury Plain (c. 3600) | Long barrow timber mortuary house | ENE‑WSW cultivation furrows then a brief cross‑pass at 90° just before mound was tipped. |

| Store Vildmose barrow, N. Jutland (c. 1700) | Timber‑built Round Barrow | Crisp cross‑ploughing respects a central primary grave stake; surrounding field retains linear drills. |

| Borum Eshøj complex, E. Jutland (c. 1900–1600) | Triple barrow group | Cross‑ploughed land parcel under each mound, but contemporary fields 50 m away keep single‑pass rigs. |

| Kilshane, Co. Tipperary (c. 3600) | “Linkardstown‑type” burial cairn | Short, deep intersecting ard lines under cairn, sealed by slab kerb. |

| South Street long barrow, Avebury (c. 3500) | Trapezoidal chalk mound | Earlier linear strip‑field; one shallow cross‑pass cut immediately before mortuary pits and chalk tipping. |

Across more than twenty published examples in Britain, Ireland, Denmark and northern Germany, the chronology clusters in two pulses:

- Middle–late 4th millennium BC – beneath Long Barrows and Linkardstown/Cotswold‑Severn chambered tombs.

- Later 3rd / early 2nd millennium BC – beneath Beaker and early Wessex round barrows.

Why cross‑plough rather than single furrows?

- Practical need – A quick second pass loosens turf and yields neat sods for the first dump of mound material.

- Symbolic break – The change of alignment (often from the prevailing ENE–WSW cultivation rigs to N–S or NW–SE crosses) forms a visible statement that ordinary production stops here.

- Labour gift – Experimental studies show cross‑ploughing a 20 × 20 m patch with a single ox and ard takes only 2–3 hours, a manageable chore for a funeral party and a conspicuous gift of effort.

- “Feeding” the dead – Ethnographers note the logic of tilling earth to provide symbolic grain; burnt cereal grains and ard‑polished flints in some barrow fills reinforce the idea.

Most field archaeologists now see both motives intertwined: practical groundwork that simultaneously enacted a rite of separation.

Are other monument types involved?

| Monument type | Evidence of cross‑ploughing? | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Causewayed enclosures | Very rare. Linear ard scores recorded in ditches at Windmill Hill and Abingdon, but no criss‑cross patterns under ramparts. | Enclosures seem to have gone up on virgin turf or scrub rather than on ploughed fields. |

| Henges / timber circles | Isolated hints (Oblong Enclosure, Dorchester‑on‑Thames) but data limited; most henges sit on alluvium or gravel where ard traces preserve poorly. | No convincing cross‑plough tract under a henge comparable to barrow cases. |

| Cursus monuments | None recorded to date; cursus ditches often slice through untouched natural sub‑soil. | |

| Linear dykes / bank barrows | One possible cross‑pass at Hindwell, Powys, under a bank‑barrow tail, but interpretation disputed. |

So far, barrows are the only monument class where cross‑ploughing is repeatedly attested; other ceremonial Earthworks use different preparatory gestures (clearance fires, turf‑packing, stake‑hole “pecking” etc.).

Conclusion

- Cross‑hatched ard marks are reliably tied to the moment just before a burial mound was raised.

- Their consistent presence beneath barrows—and near‑absence elsewhere—makes it plausible that prehistoric builders used cross‑ploughing as a liminal act, transforming arable ground into sacred ground.

- While we cannot rule out occasional purely utilitarian motives, the pattern across regions and centuries supports the idea that ploughing in two directions proclaimed a field’s last crop and the beginning of its ritual life.

Until excavators find similar patterns beneath other monument types in well‑dated contexts, cross‑ploughing remains a signature hallmark of barrow construction, signalling the shift from sustenance to sanctity in the Neolithic and early Bronze Age landscape.

Description from the HE entry

The monument includes a Neolithic long barrow 70m south east of the Long Stones standing stones and c.300m north east of the Long Stones long barrow, a contemporary funerary monument. The South Street long barrow, despite having been reduced by cultivation and partly excavated, survives as a slight Earthwork visible at ground level.

Barrow Mound

The barrow mound is aligned ESE-WNW and is known from excavation to measure 43m in length and 17m across. However, the mound has been spread by cultivation and now measures 64m in length and 43m across. Partial excavation has shown that the mound was constructed of chalk rubble tipped into a series of forty bays, created by the laying out of hurdle fences to mark out the site immediately prior to construction. This building method provided stability to the mound and guided the workforce in deciding where to dump the material quarried from two parallel flanking ditches.

Flanking Ditches

These ditches are located c.7m from the base of the mound on both sides and measure c.55m long and c.7m wide. The ditches have been gradually infilled by cultivation over the years but survive as buried features beneath the present ground surface.

Dating

Radio-carbon dating of some of the finds from the later excavation date the construction of the mound to around 2750 BC, making the monument over 4000 years old. Finds from the excavation included flint arrowheads, animal bones and fragments of pottery.

Early cross-ploughing

Below the barrow mound evidence of early ploughing was discovered, taking the form of lines of cross-ploughing incised into the chalk. This type of evidence is a rare but an important clue in understanding how the landscape was managed in the past. Excluded from the scheduling are the surface of South Street (Nash Road) and the boundary fences which border the carriageway although the ground beneath all these features is included.