"Site of Millbarrow from Windmill Hill - geograph.org.uk - 5861968" by Vieve Forward is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

Millbarrow long barrow (Winterbourne Monkton)

Millbarrow once stood on a low chalk spur 2 km north‑west of Avebury, just above the spring‑line where the Kennet valley opens onto the Marlborough Downs (NGR SU 0943 7221). From its east–west‑aligned crest the ground falls gently south to Windmill Hill and east into the Kennet valley, giving the mound clear sight of the Avebury monument complex, and easy access to water and pasture.

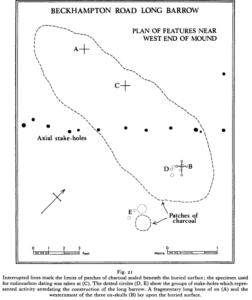

Form and building sequence

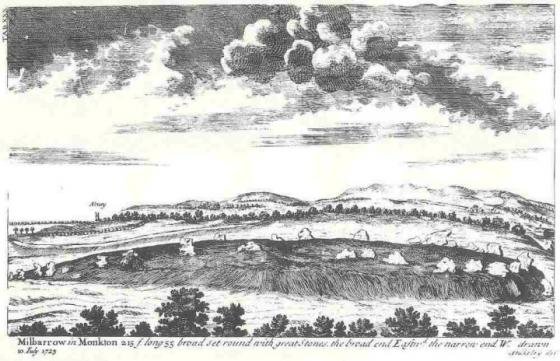

Milbarrow PLATE 28 from Abury – A Temple of the British Druids – Stukeley -1743

Stukeley’s 1743 drawing shows an elongated oval c. 65 m long and 17 m wide, fringed by upright sarsens. However, it seems the entire site was bulldozed, by accident.

A rescue excavation carried out by Alasdair Whittle in 1989 (following the accidental bulldozing in 1967) confirmed those dimensions, and also, that the long barrow featured a chalk‑rubble core‑mound was fronted at the eastern (broader) end by an outward‑facing sarsen façade and edged along its flanks by a low Peristalith of upright stones.

In addition, the barrow included two paired flanking ditches, which, it was suggested would have supplied most of the chalk for the core of the mound; the inner pair stood c. 18 m apart, the outer c. 28 m. Unfortunately, artefacts in all four ditches were extremely sparse.

Beneath the mound, Whittle recorded square post‑hole settings, shallow quarry pits and two small pits that contained articulated human bone: a probable adult and a juvenile.

Dating evidence

Four accelerator radiocarbon measurements on antler and human bone from the pre‑mound pits produced calibrated ranges of c. 3400–3000 BC (Whittle 1994, table 7). Bayesian modelling places construction in the later fourth millennium BC, broadly contemporary with the final building phase at Windmill Hill and the early use of West Kennet long barrow.

Artefacts and Eco facts

| Find‑group | Detail | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Pottery | 21 sherds of Peterborough‑ware (Mortlake style) in pit and primary mound deposits; four small sherds of Grooved Ware in a secondary ditch silt. | Ties the barrow to the mid‑Neolithic pottery sequence of the Avebury zone and shows late Neolithic revisiting. |

| Lithics | 430 struck flints, dominated by scrapers and awls; two polished‐flint flakes; two broken antler picks in quarry pits. | Confirms on‑site working of animal carcasses and tool refurbishment during construction. The antler picks provide the radiocarbon samples. |

| Human remains | Fragmentary adult mandible and juvenile long bones from the two Basal pits; no remains in the mound core. | Indicates selective, episodic deposition rather than a communal ossuary; reinforces early build date. |

| Faunal sample & soils | Cattle, pig and sheep/goat in basal soil; mollusca and Micromorphology show the site sat in an open, grazed landscape that soon reverted to scrub, then reopened in the late Neolithic. | Documents land‑use change around the monument and supports the idea that construction followed a brief cleared phase. |

A Peterborough ware Mortlake style bowl at Peterborough Museum and Art Gallery (Image thanks to Wikipedia)

Millbarrow It is one of a very few earthen Long Barrows with a stone kerb in Wessex, bridging the architectural gap between purely earthen mounds (e.g. Horslip) and fully megalithic chambered tombs.

The pre‑mound human bone provides clear evidence that mortuary activity preceded rather than accompanied mound construction, challenging the assumption that every long barrow functioned as a collective tomb.

The emptiness of the ditches and the paucity of later finds show that, unlike West Kennet, Millbarrow did not become a focus for repeated deposition. Its significance may have therefore been more significant for commemorative or territorial reasons rather than part of a long term usage in tribal funerary traditions. These burials may therefore be part of the instantiation of the monument. Perhaps the bones of an honoured ancestor we laid in order to provide some form of protection, or inspiration for the monument?

Key discoveries from excavations and fieldwork

| Evidence | What was found | Why it matters |

|---|---|---|

| Primary ground surface | Pits and post‑holes beneath the mound, two of them containing articulated human bone; carbonised antler pieces and Peterborough‑ware sherds in the lowest soils. | Shows activity on the spot before barrow construction; provides early 4th‑millennium BC radiocarbon ages (4900 ± 110 BP to 4480 ± 80 BP) that bracket the building episode. |

| Core‑mound structure | No timber chambers; instead a chalk rubble Cairn revetted by the sarsen kerb and faced at the eastern (front) end by a slight façade of larger blocks. | Confirms Millbarrow belongs to the non‑megalithic “simple long mound” tradition—valuable contrast with chambered tombs nearby. |

| Flanking ditches | Four ditch slots in total (inner and outer pairs); finds sparse—occasional struck flints, animal bone offcuts, and redeposited chalk. | Scarcity of artefacts supports the view that the monument was not used as a communal burial place or midden after completion. |

| Human remains | Fragmentary adult and juvenile bones from two pre‑mound pits; a few teeth recovered when the mound was levelled. | Suggests discrete mortuary episodes rather than repeated collective burial; strengthens the case for an early construction date. |

| Portable finds | Peterborough‑ware rim sherds, a handful of later Grooved‑ware fragments, worked‑flint scatter dominated by scrapers and piercers, two antler picks. | Links Millbarrow to the Windmill Hill pottery tradition and indicates later Neolithic re‑visits without substantial remodelling. |

Significance in the Avebury landscape

Millbarrow shares several traits with Horslip long barrow, including a single‑phase construction, paired ditches and a meagre artefact load. But it differs in its sarsen kerb and the clear evidence for limited funerary deposition before the mound was raised.

The antler and human‑bone radiocarbon determinations place it in the later fourth millennium BC, roughly contemporary with activity at Windmill Hill and West Kennet long barrow.

Because almost the entire mound was ploughed away by 1967, the 1989 rescue excavation offers the only complete record of its plan and deposits. Today the footprint is visible only as a cropmark on LiDAR. yet its