Almondbury Castle Hill (Huddersfield, West Yorkshire)

Geography Castle Hill rises to 305 m OD at the southern edge of Huddersfield, forming an outlier of hard Grenoside sandstone that caps softer Coal-Measure Shales and sandstones. Erosion has left the hill steep-sided on all flanks, with an elongated, oval summit ≈ 320 m × 150 m that dominates the Holme and Colne valley routes and commands long views towards the Pennine passes. The durable sandstone also supplied the fort’s ramparts and the later Victoria Tower. (Wikipedia, wyorksgeologytrust.org)

History & Chronology

Mesolithic flints show intermittent early activity, but the first major enclosure is an early-Iron-Age Univallate hillfort built c. 590 BC; radiocarbon and stratigraphy indicate a severe conflagration about 430 BC that left areas of reddened and partly vitrified wall cores. A second, multivallate circuit was thrown up in the later Iron Age (c. 1st century AD) before Roman contact. In the 12th century the de Lacy family inserted a motte-and-bailey castle, briefly documented in a charter of King Stephen; a short-lived medieval village laid out below the motte failed by the mid-14th century. The summit has served as a beacon-site since Tudor times and gained the Grade II-listed Victoria Tower in 1899. (hillforts.arch.ox.ac.uk, Academia, Historic England)

Archaeology

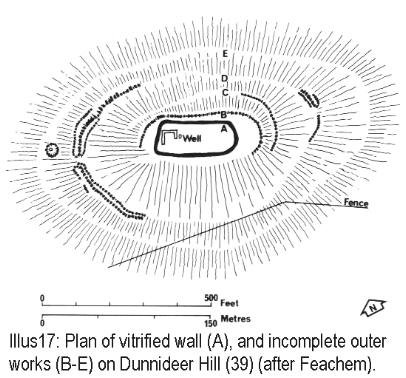

Three main Earthwork phases survive: (1) a slight univallate inner bank and ditch, (2) a bivallate to trivallate enlargement cutting across earlier ditches, and (3) the medieval motte with twin baileys overriding the Iron-Age lines. Excavations directed by W. J. Varley (1939-72) and later fieldwork recorded timber-laced sandstone ramparts showing patchy vitrification, charred tower posts, Iron-Age pottery, rotary-quern fragments, slingshots and sling moulds. Medieval levels produced a coin of Henry II and a radiocarbon-dated stake (late 1140s). The archive—plans, finds and thin sections—is curated by Kirklees Museums and the West Yorkshire HER. (Dunn Digital Copy, The Megalithic Portal)

Heritage & Access

Castle Hill is a Scheduled Monument (NHLE 1009846); the Victoria Tower is separately Grade II-listed. Managed by Kirklees Council, the hill is open grassland with car-parking below the summit road and interpretive boards on the plateau. Well-worn paths encircle the ramparts, and panoramic way-markers link the site to other Pennine landmarks. Ongoing conservation policies aim to balance public amenity with protection of the eroding Earthworks and sensitive sandstone geology. (kirklees.gov.uk)

View of Castle Hill, Almondbury, as it looks today with the Victorian tower on the top. Also, Varley plan of Almondbury.

A Vitrified Mystery

Underneath these medieval earthworks is a series of earlier defences which dates back to the early Iron Age. This was the building which burned down and it is regarded as one of Yorkshire's most important early Iron Age hill forts, it is one of Yorkshires true multi-valet hill forts and gives the impression of a tribal capital of a significant region, given the lack of similar hill forts in the region.

The first fortification was a small stockade at the south-western end. It had a single rampart of timber and stone, topped with a palisade of sharpened stakes. The one entrance was marked by a small building (guardroom?) with a hearth.

The settlement was later enlarged to cover the entire hill top. Inside this permanent village, a number a circular huts were built. More banks and ditches were added to give multiple lines of defence.

Raging in Fire

"In 430 BC, the summit of Castle Hill raged with fire. Bright red flames and clouds of black smoke climbed high into the sky from the Iron Age hill fort. But it was not until the site was excavated by my late cousin Dr William Varley in a series of digs from the late 1930's to the early 1970s that an accurate picture of its early history was revealed. This dispelled the traditional view that the Brigantian fortress at what is now Almondbury near Huddersfield had been destroyed by the Romans. The dig indicated that the fort was constructed and then abandoned centuries before the Roman occupation.

Castle Hill is a striking natural landmark nearly 1,000 feet (300m) high, covering some eight acres (3.2 ha) and surrounded by very steep slopes. Today, it is best known for the Victorian tower that stands on its top and dominates Huddersfield's skyline. It is popular with families and attracts ramblers and picnickers.

4,000 years in Occupation

But it is also the town's most important and conspicuous archaeological site and has been occupied for over 4,000 years. After reaching the summit and taking in the spectacular panoramic views of the surrounding area, visitors can wander round a series of grass covered earthen banks and ditches that circle the edge of the hill top. These belong to a motte and bailey castle constructed in the twelfth century. This type of castle was built by the Normans to ensure their security and to impose control over the area. They were fortified with a wooden stockade at strategic points dominating the surrounding countryside.

Motte and Bailey

Another plan of Almondbury, showing the outer ditches

The motte was simply a huge, flat topped mound of earth with a timber tower on top, protected by a wooden palisade. At one side of this was the bailey, an irregularly shaped enclosure. A strong timber palisade enclosed the perimeter and a deep ditch encircled the castle. The first wooden buildings were sometimes replaced with stone.

Underneath these medieval earthworks at Huddersfield and unseen by visitors is a series of earlier defences which date back to the early Iron Age. This was the building which burnt down and it is regarded as one of Yorkshire's most important Iron Age hill forts.

Castle Hill had clearly been chosen for settlement since Neolithic times because of its natural promontory position. The first fortification was a small one at the western end. It consisted of a single rampart of stone and timber, topped with a palisade of sharpened stakes. The one entrance was marked by a small guardroom with a hearth for the sentries.

An Enlarged Settlement

The settlement was later enlarged to cover the entire hill top. Inside this permanent village, a number of circular huts were built. More banks and ditches were added to give multiple lines of defence. The stone rampart at the top of the hill was strengthened by increasing its size, and it was raised and widened. On top of it, there may have been a walkway behind a stone wall and behind this, in some areas, a wooden lean-to shelter was erected. A new entrance was constructed at the eastern end, which would have had a wooden gate with a bridge over it to allow a sentry to pass from one half of the defence to the other. A rectangular enclosure containing a small two roomed hut was also added at this end, which probably protected cattle or sheep driven there in times of danger.

OS map showing Almondbury

The gate was approached by a hollow way leading to the bottom of the hill. If an assault was made on it, the attackers would find themselves in a narrow space and in cross-fire from defenders manning the ramparts on wither side. Finally, an outer bank and ditch ran round the base of the hill with an entrance in the south west corner.

Construction

The construction of this great fortress would have required a large labour force, which suggests that the countryside supported "an extensive and well-organised society". The final building work dates to the fifth century BC but it was not to last very long. In 430 BC, less than half a century later, this magnificent stronghold was burnt to the ground. A great raging fire spread through the timbers, turning them into charcoal. The blaze must have been visible for miles around and was so intense that it destroyed substantial parts of the ramparts. The fort was then allowed to tumble down, fell into ruin and was abandoned.

Who were the attackers?

Castle Hill, Huddersfield

But who were the attackers; a hostile Celtic tribe or the Romans? The date of 430BC was arrived at by analysing the burnt clay from the ramparts. It means that the site was destroyed and abandoned long before the Romans came to this country.

Archaeological evidence has shown that the ramparts were not fired from outside and the source of the fire lay inside them. But if the fort was not sacked by a river Celtic tribe, what happened? It is likely to have been the result of spontaneous combustion of the timbers but the burning down of the fort could have been either accidental or deliberate. If it was an accident, the Iron Age people decided not to rebuild it and moved on. Alternatively they may have abandoned. Castle Hill in favour of an undefended lowland settlement, setting it alight before or after they left it so that no other tribe could occupy it.

Another aerial view of Almondbury

Left unoccupied for 1700 years

The site was not occupied again for 1,700 years until the building of the motte and bailey castle in the twelfth century. The medieval work removed the outer bank and destroyed most traces of the interior Iron Age occupation.

At one time, Castle Hill was the stronghold of a powerful Celtic chief. It would have been full of noise and bustle and vigorous life. During the excavations, a variety of Iron Age pottery was found in the shelters behind the inner rampart, which is an important aid in dating the site. The finds represent jars which could have come to the fort by trade or barter. What the inhabitants of Castle Hill had to offer may have been skins, as post holes were found which may have been drying frames. Inside the fort would have been the huts of farmers. Who tilled the fields below the pastured cattle and sheep, sheds and cattle pens, storage pits for grain and rubbish pits. The tranquillity and commanding views which please the visitor today originally gave the lookouts an early view of approaching enemies. " Raymond Varley.

Above. View Southeast showing the rampart and the Well within the fort.

North West of Almondbury, evidence of old field systems surround Almondbury, indicating an extended period or peacetime use.

View South West, again Almondbury is surrounded by high quality flat pasture.

Air view from multimap.com 2nd December 2002

The Burnt Ramparts

"Excavation and the use of a sensitivity meter confined to the Inner and Second ramparts as they existed in Stage 6, Phase Six of the pre-Roman period. The burning varies in intensity within the ramparts in which it occurs. There are parts of these same ramparts which are not in the least affected only a few centimetres from other sections which were intensely affected. There are some parts of the Inner and Second ramparts which are not affected at all in their entirety from top to bottom, even though they stand up vertically against rampart cores which were burnt to a cinder, or to brick dust."

"Officials of the Yorkshire Division of the National Coal Board, who examined that section in the field, were of the opinion that the effects they saw resembled those they were familiar with in coal waste-tips and which were attributed to spontaneous combustion. Oddly enough, Professor Robert Newstead held a similar view of the ramparts I excavated at Maiden Castle, Bickerton and the Castle Ditch, Eddisbury. In both these cases, there was visual proof that the heat had not been applied outside the revetments of Triassic sandstone within which the affected cores were encased." William Varley - Excavations at Almondbury, 1972

"Castle Hill, Huddersfield" by r44flyer is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

"Castle Hill, Huddersfield" by r44flyer is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Castle Hill’s imposing silhouette hides a great prehistoric fort, Norman castle and Victorian tower. Thanks to Varley’s trenches and the 1995 RCHME survey we have a solid structural framework, yet key chronological pins, remain to be driven. It is therefore both a celebrated landmark for Huddersfield and a live research asset for Iron-Age, and medieval research.

4,000 years of occupation on Huddersfield’s skyline

Setting & topography

A flat-topped cap of hard Grenoside sandstone rises c. 275 m OD (≈ 902 ft) above the Holme–Colne confluence, dominating routes through the Pennine fringe. The plateau is about 3.7 ha in extent and is naturally defensible on every side except the south-east, where a narrow spur gives access. (Dunn Digital Copy, Atlas of Hillforts)

Archaeological sequence in outline

| Period | Physical evidence | Key dating evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Late Bronze–Early Iron Age | Univallate contour rampart and ditch enclosing the summit. | Radiocarbon estimate for primary construction c. 555 BC (Varley’s charcoal sample). (Wikipedia) |

| Middle–Late Iron Age | Enlargement to a bivallate/multivallate fort with up to five banks on the easier south-eastern approach; severe burning produced patchy vitrification, rare in England. | Charcoal lenses and heat-spalled stones recorded in 1970 trench. |

| Roman & post-Roman | No structural levels; stray finds only, implying abandonment during the Roman presence. | Varley noted a complete absence of Roman layers in all cuttings. |

| Norman motte-and-bailey (c. 1130-1200) | Oval inner bailey (80 m × 60 m) defined by a rock-cut ditch 24 m wide & up to 9 m deep; timber palisade later replaced by a stone shell-keep (now gone). | Stake from palisade slot radiocarbon-dated to late 1140s; coin of Henry II (c. 1160) sealed in rampart. (wyjs.org.uk) |

| Planned medieval settlement (c. 1310-1340) | Aerial photographs show a gridded street and burgage plots in the lower bailey; pottery is scarce. | Earthwork plan and RCHME survey. (Historic England) |

| Early-modern beacons & fairs | Documentary refs. from 1588 Armada beacon; fair recordings 17th–19th c. | — |

| Victorian landmark | 32.3 m-high Victoria Tower (1897-99) built on the medieval keep mound. | Architectural record. |

"1930s photograph of Castle Hill" by huddersfieldexposed is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

"1930s photograph of Castle Hill" by huddersfieldexposed is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Chronicle of archaeological work

| Years | Lead investigators & methods | Contribution |

|---|---|---|

| 18th–19th c. antiquaries | John Warburton (1720s), F. Dinsdale (1843) measured plans. | First recognition of multi-phase banks and Norman ditch. (Realyorkshireblog) |

| 1939; 1946-47; 1969-72 | W. J. Varley’s long-running excavations: 14 trenches through ramparts, ditches & baileys. | Defined three prehistoric building phases; discovered vitrification; identified Norman palisade slot & medieval house platforms. |

| 1970 specialist trench | Varley & Leeds University: archaeomagnetic and soil-Micromorphology sample from burnt rampart. | Proved in-situ firing at >1 100 °C. |

| 1995 RCHME analytical survey | Full EDM plan, earth-work modelling, reassessment of Varley’s ‘annexe’. | Showed fifth bank on E is natural Scarp + field lynchets; produced base-line used by management plan. |

| 2006 Conservation Management Plan | Kirklees Council/WYAS desk-based review & condition audit. | Highlighted erosion hotspots and need for visitor-route control. |

| 2020s digital heritage | Drone LiDAR & photogrammetric mesh for public VR tours (Kirklees). | Confirms minimal earthwork loss since 1995; offers new platform for research-grade modelling. |

Key structural features today

- Prehistoric defences – twin ramparts still stand 1.8 m high on S & E; quarry-scoops behind inner bank mark where sandstone was robbed for later walls.

- Norman ditch & motte – the rock-cut moat is best preserved on the north side; the summit of the motte is partly masked by the tower plinth.

- Medieval village plots – low lynchets and hollow-ways on the east terrace align with aerial-photo grid.

Why the hill remains significant

- Rare English vitrification – Alongside Wincobank and Castercliff, Castle Hill provides one of the few English cases where Iron-Age ramparts were deliberately burnt, allowing direct comparison with the Scottish corpus.

- Layer-cake of power – Unbroken sequence from prehistoric tribal centre to Norman caput and Victorian civic monument offers a textbook in re-use of place.

- Methodological landmark – Varley’s multi-decade excavation, followed by a high-resolution RCHME metric survey, makes the hill a classic study in how interpretive models evolve with new techniques.

| Topic | Why it matters | Next step |

|---|---|---|

| Precise date of vitrification | Existing charcoal gives only a broad mid-1st-millennium BC range. | Fresh rampart coring for paired archaeomagnetic / radiocarbon dating. |

| Extent of 14th-c. settlement | Only surface traces known; could refine story of deserted medieval towns. | Targeted magnetometry + palaeo-soil coring in lower bailey. |

| Roman-era activity | Absence of finds may mask short-lived strategic use. | Systematic metal-detector survey under licence & small test pits. |