Grid ref: NJ 612 281 Ordnance Survey Landranger series sheet no. 37

Grid ref: NJ 612 281 Ordnance Survey Landranger series sheet no. 37

Dunnideer Fort

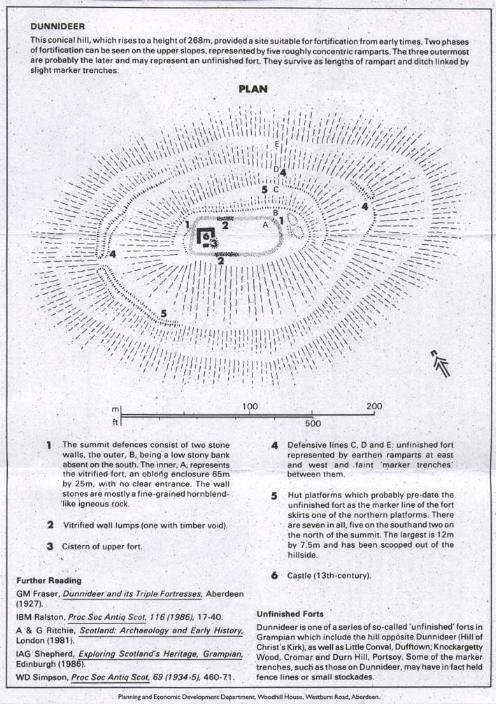

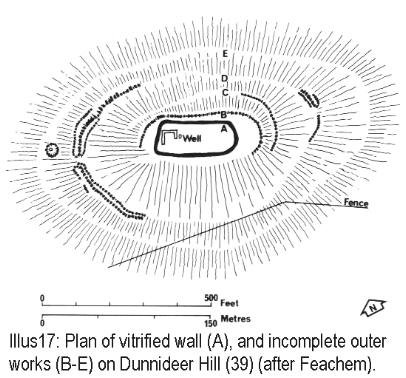

12 miles NW of Inverurie. Access to the group of monuments on Dunnideer Hill is by a signposted footpath from minor road from Insch to Clashindarroch Forrest about 1 mile W of Insch , off the B 992. The Medieval Castle, the most prominent feature in the hill, stands inside, and is built from the debris of, an oblong vitrified fort, a maximum length approximately 70 m, which crowns the summit.

Outworks

Outworks, most clearly marked on the E, may be associated with this phase. Early features in the interior include a depression adjacent to the castle, which is probably the remains of a cistern or a well. A rectilinear building, set at right angles to the main axis of the vitrified fort, is certainly later in date. Further out and down-slope, traces of slight banks and ditches can be noted: these represent an unfinished defensive scheme, almost certainly later in date than the vitrified fort. On both the N and S slopes, traces of what appear as small grass-covered quarry scoops, fronted by level platforms c 8 m in diameter, can be noted. These represent the stances for timber round-houses, which may date from as early as 1200 BC.

"Dunnideer Monument" by Mike Rawlins is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0"

Dunnideer Hillfort – what the evidence tells us so far

Below is a site-centred account that weaves the physical remains together with every episode of investigation, showing how each enquiry refined – and sometimes overturned – earlier ideas.Setting, form and survival

| Attribute | Details |

|---|---|

| Location | Hill of Dunnideer, 265 m OD, on the western rim of the Garioch, Aberdeenshire (NGR NJ 6128 2756) – a conical knoll overlooking the Bennachie gap and the main Dee–Spey route. |

| Plan | Inner oblong enclosure c. 67 × 27 m, defined by a timber-laced wall 4 – 5 m thick whose core is intensely vitrified on all flanks except the N. Two concentric ramparts and traces of platforms descend the hill, taking the maximum defended area to c. 2.2 ha. |

| Medieval reuse | A single-cell masonry tower-house (15 × 12.5 m in plan; walls 1.9 m thick) was erected about 1260 CE inside the Iron-Age shell, quarrying large chunks of the slag-fused rampart for building stone. It is regarded as one of the earliest stone tower houses on mainland Scotland. |

Timeline of investigation

| Date & actor | Work carried out | How it changed our understanding |

|---|---|---|

| 1770s-1820s – Enlightenment antiquaries | Williams (1777) and Laing (1828) sketched and measured the “Dunnydure” ruins. | First recognition of a man-made wall fused by fire; assumed “Roman-era” origins. |

| 1934 – Scheduling & RCAHMS survey | Fort scheduled; Royal Commission produced a dimensioned plan with five defensive lines. | Confirmed that the oblong vitrified core is only the innermost of several ramparts. |

| 1950s-60s – Feachem & OS field teams | Systematic walkover, tape-and-offset survey, classification as an “oblong, gateless, vitrified fort” within a NE Scottish series. | Placed Dunnideer in a regional group alongside Finavon and Tap o’ Noth, emphasising its timber-laced construction. |

| 1974-76 – Geological/experimental work | Samples from the rampart used in the first laboratory study of vitrified basalt; OS revision recorded the fire-glazed blocks. | Demonstrated in-situ melting at > 1100 °C and scotched ideas of lightning or volcanic action. |

| 2005 – Wildfire damage assessment (Badger & Dunwell) | Emergency survey and test-pits after a grass fire scorched the summit. | Located fresh stretches of rampart face and internal scoops hidden by turf. |

| 2007-10 – Hillforts of Strathdon project (M. Cook) | Keyhole trench through the inner wall; bulk slag sampled for radiocarbon and archaeomagnetism: Integration with EDM terrain model. | Two radiocarbon dates on primary charcoal (390-190 cal BC & 370-160 cal BC) and an archaeomagnetic range of 606-257 BC set construction/destruction in the mid-Iron Age (≈ 400-250 BC). |

| 2014-16 – Atlas of Hillforts survey | High-resolution GPS mapping of all ramparts. | Demonstrated that outer lines form a single large enclosure, not disconnected ‘outworks’, and hinted at terrace-houses on the SW flank. |

| 2024-25 – Heritage & outreach | 3-D digital model and 1 : 150 exhibition replicas unveiled by Insch Connection Museum. | Popularised the idea that Dunnideer’s tower is built upon – not merely within – an earlier power-centre. |

What the datasets now suggest

- Chronology – All secure scientific dates cluster in the 3rd–2nd centuries BC for the vitrification event, while architectural comparison makes a late-13th-century date likely for the tower house.

- Construction method – Excavation exposed five surviving courses: inner and outer faces of basalt rubble with a timber lacing, whose charring fuelled the vitrification. No doorway was found in the excavated stretch, aligning with the ‘gateless’ morphology of the oblong-fort series.

- Scale of firing – Charcoal lenses up to 0.3 m thick on the rampart’s interior suggest deliberate stacking of brushwood against the wall, echoing firing strategies tested experimentally by Childe & Thorneycroft in the 1930s.

- Outer defences – Two lower ramparts encircle c. 2 ha; whether they are contemporary with the vitrified wall or later Early Historic refurbishments remains unresolved pending excavation of their banks.

|

|

Why Dunnideer matters to research practice

- Type-site for “oblong, gateless, vitrified forts” – Together with Tap o’ Noth and Finavon, Dunnideer anchors debate on functions ranging from elite citadels to ceremonial enclosures.

- Dating techniques in action – It is one of the few vitrified forts where radiocarbon, archaeomagnetism and micro-petrography have all been applied to the same rampart, making it a calibration point for studies elsewhere.

- Medieval adaptation – The 13th-century tower shows how Iron-Age strongholds were recycled as ready-made platforms for high-status residences, a theme echoed at sites like Castle Craig and Edinburgh’s Castle Rock.

- Public visibility – Its single standing wall, visible for 30 km across the Garioch, and the short 15-minute hill walk make it an ideal teaching ground for explaining vitrification, multi-period reuse and heritage management in one visit.

Outstanding research questions

| Topic | Why it matters | Next steps |

|---|---|---|

| Sequence of outer ramparts | Pinpointing whether they are Iron-Age additions or Pictish/Early-Med settlement could reveal long-term continuity. | Targeted coring & optically-stimulated luminescence dating. |

| Purpose of vitrification | Was it defensive, symbolic, or a termination rite? | Comparative micro-CT of slag vesicles vs. experimentally fired wall-cores. |

| Iron-Age economy | No artefact scatter is yet securely associated with the fort interior. | Open-area trench to sample floor deposits & obtain palaeobotanical microfossils. |

| Tower-house phasing | Establishing whether the tower predates Balliol’s 1260 charter could push back the start of Scottish tower-house architecture. | Mortar-radiocarbon (‘lime-burp’) dating and architectural Photogrammetry. |