"Mote of Mark from sea shore path - geograph.org.uk - 6273954" by Andrew Curtis is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

"Mote of Mark from sea shore path - geograph.org.uk - 6273954" by Andrew Curtis is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

Mote of Mark – a Dark-Age citadel above Rough Firth

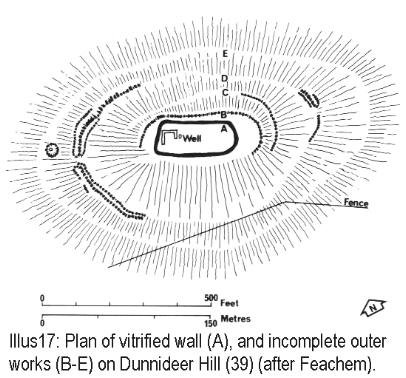

Setting & basic layout

Located on a granite knoll (45 m OD) on the east shore of Rough Firth between Rockcliffe and Kippford, Dumfries-and-Galloway (NGR NX 845 540). The west and south faces drop almost sheer to the estuary; access is by a narrow neck on the north-east. (hillforts.arch.ox.ac.uk, Britain Express)

Defences – A single timber-laced stone rampart, c. 4 m thick, once ringed the 0.14 ha summit; most blocks were tumbled downslope after a fierce burning that fused parts of the core into green-black glass. A slighter outer bank and ditch skirt the easier north-east approach. No definite entrance has been located. (Canmore)

Chronicle of investigation

| Date | Investigators & method | What they added |

|---|---|---|

| 1755–1893 | Roy’s Military Map, R. Riddell (1790) & J. Coles (1893) sketch-survey | First published notice of a “vitrified fort”; rough plan and section. (hillforts.arch.ox.ac.uk) |

| 1913 | Alexander O. Curle cut 13 trenches across rampart and interior | Proved timber-lacing + vitrification; recovered continental glass, E-ware pottery, 400+ clay mould fragments, crucibles and high-status metalwork, revealing industrial activity. (journals.socantscot.org) |

| 1973 & 1979 | Lloyd Laing & David Longley reopened Curle’s area and trenched the N & S walls | Produced a full stratigraphic sequence, mapped rampart faces, identified five structural/occupational phases and sampled vitrified slag. (books.casematepublishing.com, hillforts.arch.ox.ac.uk) |

| 2006-13 | Watching briefs, bracken-die-back surveys & UAV imagery (HES) | Monitored erosion, located terrace platforms below the summit. (Canmore) |

| 2022 | Publication of The Mote of Mark monograph | Synthesised all finds, provided new scientific dating and specialist analyses. (books.casematepublishing.com) |

Key finds & specialist results

Imported table-wares – 55 sherds of Gaulish E-ware and two Late-Roman (LR 2) amphora fragments place peak occupation in the mid-6th century AD. (books.casematepublishing.com, Canmore)

High-status craft debris – 482 clay mould fragments (Penannular brooches, enamel studs), crucible slag and bronze/iron off-cuts indicate on-site non-ferrous metal-working aimed at élite goods. (books.casematepublishing.com)

Glass & gaming pieces – Vessel shards from Frankish glass beakers and a bossed glass gaming counter underscore long-distance connections. (books.casematepublishing.com)

Animal bone & food waste – Dominance of cattle and high proportions of red-deer venison fit a short-lived, high-status residence rather than a farming hamlet. (books.casematepublishing.com)

Dating & historical horizon

Radiocarbon assays on rampart charcoal and occupation layers converge on c. AD 550–700; artefact typology agrees, framing the fort within the post-Roman kingdom of Rheged and the wider Irish-Sea trading zone. (hillforts.arch.ox.ac.uk, books.casematepublishing.com)Why the Mote matters

Classic vitrified wall south of the Clyde/Forth line – a laboratory for studying firing techniques beyond the better-known Highland forts. (Canmore)

Classic vitrified wall south of the Clyde/Forth line – a laboratory for studying firing techniques beyond the better-known Highland forts. (Canmore)

Industrial powerhouse – unparalleled quantity of moulds and crucibles shows that prestigious metal-working was embedded inside a royal seat, not farmed out to satellite workshops. (journals.socantscot.org, books.casematepublishing.com)

Trade cross-roads – Imported wine amphorae, fine pottery and glass prove direct contact with Atlantic Gaul and the Mediterranean during Britain’s so-called “Dark Ages”. (Canmore, books.casematepublishing.com)

Tightly dated destruction – Coherent 6th-century radiocarbon suite plus vitrification raise the prospect that the fort was deliberately torched during early Northumbrian expansion. (hillforts.arch.ox.ac.uk)

Outstanding questions & research potential

| Issue | Why it matters | Next step |

|---|---|---|

| Who burned the rampart? | Could link the fire to named conflicts in Historia Brittonum. | Pair archaeomagnetic & micro-CT slag studies to refine burn episode. |

| Extent of craft zoning | Interior still partly unexcavated. | Targeted geophysics and micro-excavations in central hollow. |

| Outer terrace platforms | Possible worker huts or later reuse? | Coring & OSL dating of terrace fills. |

| Landscape integration | How did the fort control estuary traffic? | Viewshed & catchment modelling tied to LiDAR. |

Vitrified Fort

The Mote of Mark is a defended hilltop overlooking the Urr estuary. It was the court or citadel of a powerful Dark Age chieftain, possibly one of the princes of Rheged. The site was occupied during the 6th century and appears to have been destroyed by fire in the 7th century.

The top of the hill was enclosed by a massive stone and timber rampart. Inside was a timber hall surrounded by a huddle of workshops and stables. This was a wealthy site with trading contacts across Europe. Finds from the excavations include glass beads and wine jars from central France and glassware from Germany. Local craftsmen produced elegant bronze jewellery in a distinctive Celtic style.

The tumbled remains of the ramparts can still be seen, and an on-site interpretation panel has an atmospheric reconstruction of the fort.

Size: 8 ha (20a)

Legendary and Literary Background

https://panther.bsc.edu/~arthur/others.html

This fort was occupied from the 5th to 7th centuries, smack-dab in the Arthurian time frame. At the pinnacle of its prominence, it was a well-fortified trading and manufacturing centre. Excavations in 1913 and 1973 unearthed a large, circular timber hut and evidence of metalworking. These people seemed to have imported raw materials--iron from the Lake District and jet from York--to produce interlaced jewellery, brooches, and sundry metalwork. They imported luxuries as well--pottery from Bordeaux and glass from the Rhineland were found. Such prosperity suggests that this fort may have been the stronghold of a smaller British subkingdom.

Defences

The primary defences consisted of stone and timber walls, and there was a timber gate for the main entrance on the southern slopes. In the 7th century, though, these defences failed. The outer wall shows evidence of vitrification, a condition when extreme heat causes stones to fuse together. Many believe that this was the result of an attack by the Angles--Anglian runic inscriptions were found at the site--though some say that the walls were purposely vitrified to strengthen them.

The only thing truly connecting this fort with the Arthurian legend is the name, its period of occupation, and its proximity to Trusty's Hill.

Dating of Mote of Mark

Radiocarbon determinations on the burnt rampart

Five charcoal samples taken in the 1973 and 1979 campaigns were run at the Scottish Universities Reactor Centre (prefix SRR/ GU). Calibrated with IntCal20, they cluster like this:

| Lab code | ¹⁴C BP | 2σ calibrated span (95 %) | Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| SRR-321 | 1491 ± 42 | AD 430 – 640 | Charcoal in vitrified wall core |

| GU-1313 | 1570 ± 100 | AD 240 – 670 | Charcoal lens in secondary wall tumble |

| GU-1314 | 1525 ± 100 | AD 250 – 800 | Charcoal below paving inside gate |

| GU-1315 | 1595 ± 100 | AD 220 – 660 | Charcoal under metal-working floor |

| GU-1316 | 1525 ± 100 | AD 250 – 800 | Charcoal in furnace rake-out |

Taken together, the highest‐probability overlap lies in the mid-6ᵗʰ to early-7ᵗʰ century AD.

Imported artefacts that peg the main occupation to c. AD 550–625

Gaulish “E-ware” kitchen pottery – a coarse orange fabric distributed to Atlantic Britain c. AD 550-650. Fifty-five sherds came from Curle’s and Laing & Longley’s trenches. (potsherd.net, Internet Archaeology)

Late-Roman Amphora type 2 (LRA-2) – neck and body fragments whose production and export peak in the later-6ᵗʰ century. (levantineceramics.org)

Frankish glass beaker shards & a bossed gaming piece of Merovingian type, again typical of high-status sites between AD 550 and 620. (Dark Age Digs)

Because these imports all arrived by sea and are unlikely to have lain around for generations, they reinforce the radiocarbon window.Stratigraphic pointers

Laing & Longley’s stratigraphy shows:- Construction of the timber-laced rampart.

- A short phase of intensive non-ferrous metal-working (hundreds of clay mould fragments and crucibles).

- Catastrophic burning and vitrification that collapsed the wall and sealed the workshop floors.

The charcoal dated above comes from that conflagration horizon, so the scientific dates time-stamp the fort’s destruction, not just its use.

Putting the pieces together

| Evidential strand | Convergent date-band |

|---|---|

| ¹⁴C on rampart & industrial floors | AD 430–640 (modal peak c. 550–600) |

| E-ware imports | AD 550–650 |

| Frankish glass & LR 2 amphora | AD 550–620 |

| Atlas of Hillforts synthesis | Start c. AD 550, end c. AD 700 |

Consensus view: the Mote of Mark was founded in the mid-6ᵗʰ century (around AD 550), flourished for perhaps two or three generations as a royal/workshop centre within the kingdom of Rheged, and was destroyed by fire—very likely in the early-7ᵗʰ century (c. AD 600–630).

What is still uncertain?

- Whether there was a short reoccupation after the burn (uppermost layers were badly eroded before excavation).

- Which enemy—or internal faction—set the fort ablaze; historical candidates range from Bernician Northumbria to dynastic rivals within Rheged.

- Precise length of the metal-working episode (industrial debris is dense but stratigraphically compressed).

Bottom line: the Mote of Mark is not undated. Multiple radiocarbon assays, tightly datable continental imports and coherent stratigraphy all point to a main life-span of roughly AD 550 to 630, with the vitrified rampart sealing the very end of that story.