"Kilburn White Horse" by jamesfcarter is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

"Kilburn White Horse" by jamesfcarter is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0Kilburn White Horse

"Kilburn White Horse" by jamesfcarter is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

"Kilburn White Horse" by jamesfcarter is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0The Kilburn White Horse

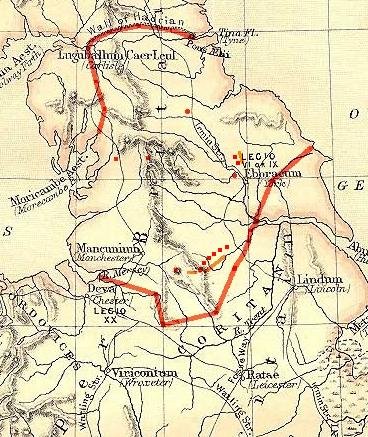

The Kilburn White Horse is a large chalk hill figure cut into the limestone of Roulston Scar, the steep escarpment that defines the western edge of the Hambleton Hills in North Yorkshire. Carved in November 1857 and measuring roughly 97 by 67 metres, it was conceived not as an ancient relic but as a deliberate Victorian creation: a striking silhouette of a horse gleaming white against the natural rock and turf, visible for miles along the A19 and from passing trains on the East Coast Main Line. Positioned just north of the village of Kilburn, this hill figure occupies a promontory that had for centuries watched over the vale of the River Rye below, yet it owed its modern form entirely to local ambition and mid-19th-century sensibilities.

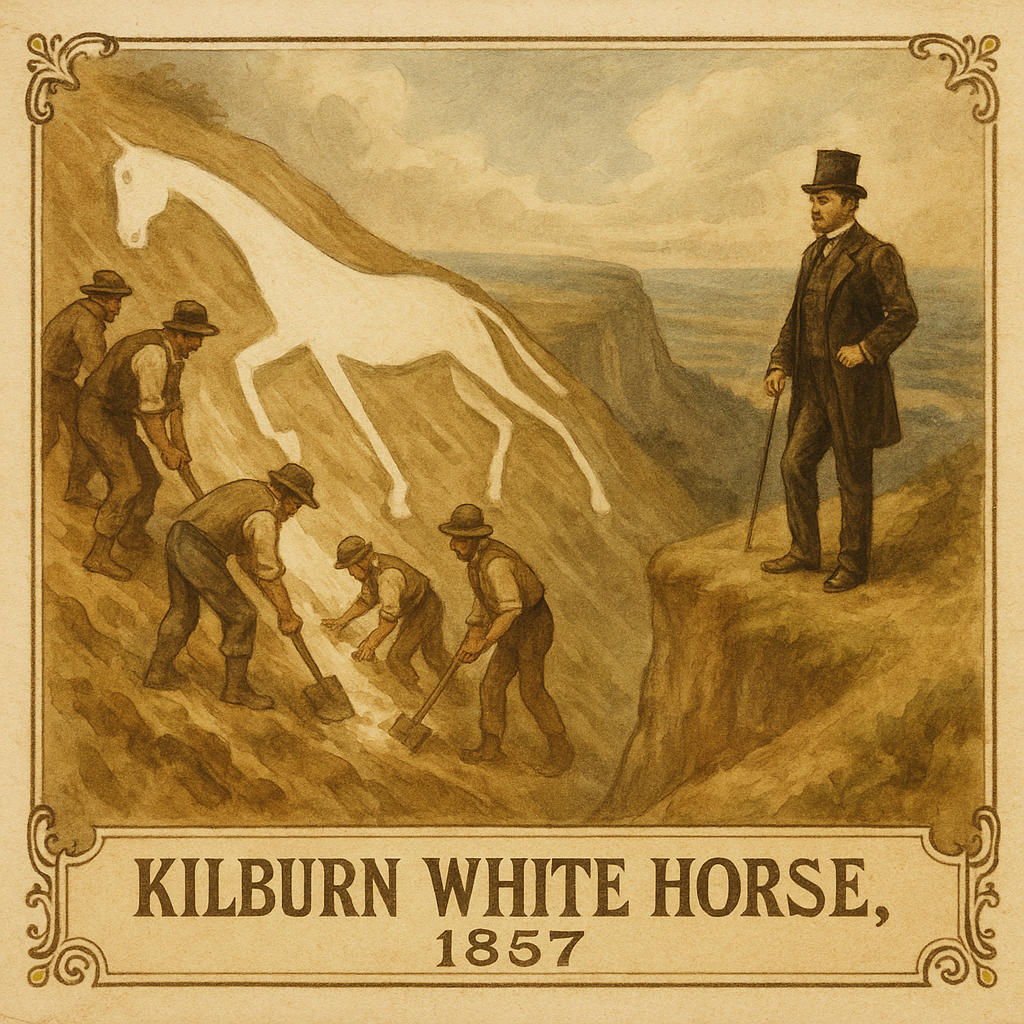

AI Impression of a postcard of Kilburn White Horse from the period

The origin of the Kilburn horse lay in a combination of Romantic landscape tastes and burgeoning antiquarian enthusiasm. By the mid-Victorian era, British landowners and local dignitaries were keen to fashion their estates with “follies”—artificial ruins, shrubberies, grottoes and other eye-catching features—that evoked a poetic sense of history. Equally, influential was the rediscovery and popularization of prehistoric monuments: the Uffington White Horse in Oxfordshire, long admired by poets and early archaeologists alike, became emblematic of a heroic, pre-Roman Britain.

Thomas Taylor and John Hodgson

It was in this spirit that Thomas Taylor, a local mill owner and antiquary, persuaded John Hodgson, the village schoolmaster, and a handful of volunteers to cut away the turf and topsoil, exposing the pale limestone beneath and then “dress” the outline with imported chalk. Though contemporary newspapers spoke of employing local labour to relieve winter unemployment, the modest scale of the workforce and the enthusiasm of unpaid schoolchildren suggest the true driving force was communal pride and a desire to anchor Kilburn’s identity in an imagined ancient past.

The White Horse at Kilburn was an early example of experimental and cultural archaeology. In recreating the form of a prehistoric hill figure, the villagers were asserting continuity with an ancestral Britain—one celebrated in the pages of antiquarian journals and in the Romantic verse of Wordsworth and Scott. This impulse went beyond mere nostalgia; it reflected a Victorian belief in the moral and educational power of the landscape. To walk the ridge and behold the horse was, in their view, to reconnect with deep-time virtues of endurance, kinship with nature, and the solemn grandeur of bygone ages.

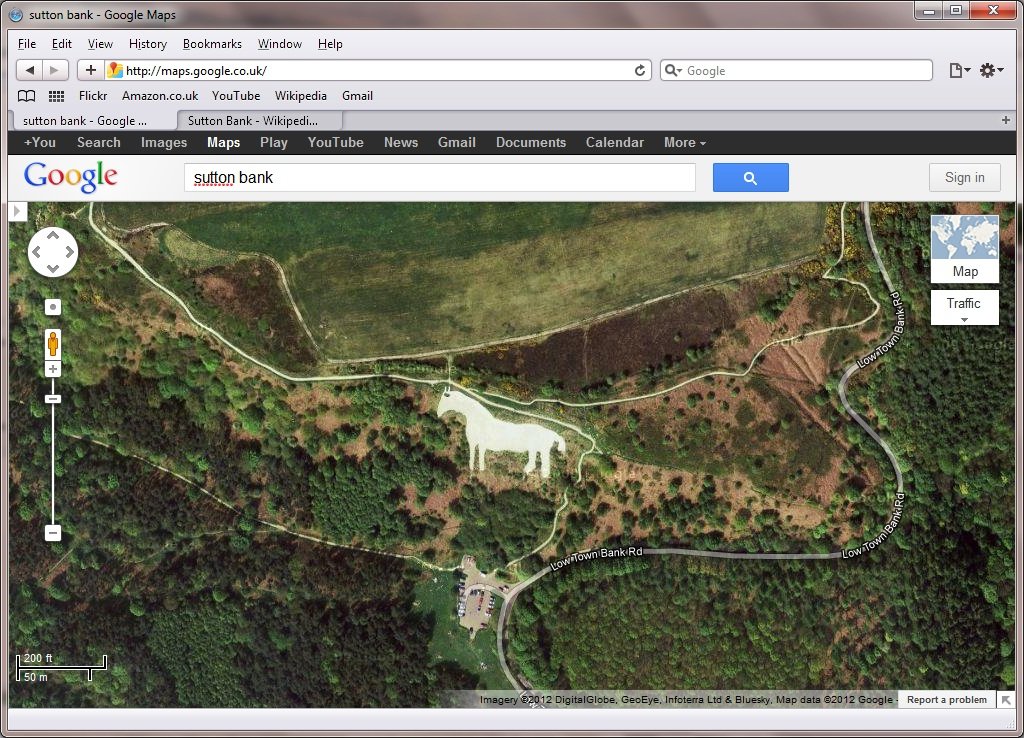

"Kilburn White Horse as seen from space" by

"Kilburn White Horse as seen from space" by Date & makers

First cut in November 1857 under the auspices of local businessman Thomas Taylor, who funded and designed the scheme. On‐the-ground labour appears to have been a small team of volunteers led by schoolmaster John Hodgson (and possibly Taylor’s pupils), rather than a large, paid workforce (en.wikipedia.org, jo-throughthekeyhole.blogspot.com).

Technique & materials

The topsoil was dug away from the limestone hillside to expose the pale rock, then dressed with imported chalk chips (originally burnt lime, later Wolds chalk) to give the figure its bright white appearance (en.wikipedia.org, atlasobscura.com).

Dimensions

318 ft long × 220 ft high (97 m × 67 m), covering about 1.6 acres (en.wikipedia.org).

Victorian Landscape Follies & Antiquarian Revival

Romantic Picturesque & estate improvements

From the late 18th c., landowners remodelled parks with “follies” (fake ruins, grottos, hill figures) to create dramatic views. By mid-Victorian times, this aesthetic—rooted in Romanticism—was deeply woven into notions of genteel taste and moral uplift.

Antiquarian nationalism

The 19th c. saw a burgeoning interest in Britain’s prehistoric past: excavations of Barrows and Roman villas, the founding of the Society of Antiquaries (1707) and later the Archaeological Institute (1844). Figures like the Uffington White Horse (Iron Age) became emblems of an ancient “British” identity, valorised in poetry and antiquarian publications.

Replica hill figures as cultural statements

By copying the Uffington model, communities across England (Litlington 1838, Westbury 1778 restored 1804, Pewsey 1812, Kilburn 1857) tapped into a shared narrative of continuity with a heroic, pre-Roman past (en.wikipedia.org).

Beyond “Employment Relief”

Local unemployment was often given as the public-facing rationale for large Earthworks (e.g. estate-owner-funded ditch digging), but in the Kilburn case the small number of hands involved suggests a voluntary, civic-pride enterprise rather than a work-scheme.

Cultural and educational motives

Taylor, having travelled for his mercantile work, was inspired by southern hill figures; Hodgson (the schoolmaster) likely viewed the project as both a hands-on lesson in local geology and antiquity, and a means of stoking community identity.

National mood of “useful archaeology”

Mid-Victorian Britain prized the idea that studying and even replicating ancient monuments reinforced moral virtues—order, continuity, and reverence for the landscape’s “deep time.”

Significance & Legacy

No medieval or prehistoric origins: unlike genuine Iron-Age sites, Kilburn’s horse is purely Victorian, yet it adopts the idiom of prehistory to forge a sense of timelessness in the local landscape. Ongoing maintenance as ritual: volunteers still repaint it every few years (most recently 2022 at a cost of ~£20 000), sustaining that same spirit of communal stewardship (en.wikipedia.org, atlasobscura.com). Touristic and symbolic role: visible for miles, it functions today as both a landmark on the A19/East Coast Main Line and a living reminder of how the Victorians sought to reinvent—and in a sense re-inhabit—their own mythic past.By situating the Kilburn White Horse within the mid-19th-century “folly” tradition, antiquarian nationalism and the Picturesque movement, we can see it not so much as a job-creation scheme but as a conscious act of cultural archaeology—an attempt to reconnect a modern community with an idealized prehistoric Britain.