Bubenec plough marks - Institute of Archeology of Academy of Sciences

Early Neolithic ploughing at Bubeneč

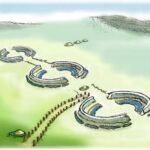

Quite recently, initial excavation evidence from Bubenec, close to Prague was first announced to the public, pending full publication. As part of that media activity, the head archaeologist for the dig, Petra Maříková Vlčková explained that the excavation; below the future Canadian Embassy, in Prague’s Bubeneč district, cut through almost two metres of undisturbed deposits – a rarity in Central Europe. At the very bottom of this “Tell of Bubeneč”, the team exposed a set of parallel furrows impressed in the prehistoric ground surface.

What exactly was found

- A band of clean, linear, parallel plough‑marks running across the lowest (earliest) occupation level.

- No intersecting or “cross‑hatched” furrows of the kind normally recorded beneath Eneolithic burial mounds.

- No trace of a burial mound or Barrow above the furrows.

- Associated pottery and hearth debris suggest an early Eneolithic date (c. 3500 BC), but radiocarbon samples are still in the lab.

Why the find matters

- If the date is confirmed, the Bubeneč furrows double the age‑range of plough evidence in the Czech lands.

- They would rank among the oldest securely identified plough‑marks in Central Europe.

- The discovery shows that arable cultivation had reached Prague’s hinterland 700–800 years before the Corded Ware horizon, previously thought to mark the first heavy tillage here.

- The furrows demonstrate that early farmers on the Vltava flood‑terrace were already using an ard or scratch‑plough capable of cutting long, straight drills – suggesting fields large enough to justify animal traction.

Linear versus crosswise ploughing

- “Crosswise” (criss‑cross) patterns under Barrows have long been labelled ritual ploughing, perhaps symbolically “feeding” the dead.

- Bubeneč presents only single‑direction furrows, more consistent with everyday cultivation.

- The contrast hints at two contemporaneous ploughing traditions:

- Functional, linear tillage for crops (Bubeneč).

- Symbolic, crosswise furrows beneath barrows (ritual contexts elsewhere).

Wider implications raised in the interview

- Early Eneolithic farmers here were already experimenting with metal (copper/early bronze) and expanding long‑distance trade links to the Mediterranean.

- More efficient ploughing would have boosted crop yields and population density, laying groundwork for sharper social hierarchies.

- The tell‑like build‑up at Bubeneč shows continuous re‑occupation and waste accumulation, implying that the same fertile riverside plot remained desirable across millennia.

Ritual‑versus‑functional ploughing: the core argument

Across north‑west Europe archaeologists sometimes find ard‑ or plough‑marks sealed beneath Neolithic and Bronze‑Age barrows. Two patterns repeat: (1) dense, cross‑hatched furrows that criss‑cross at right‑angles and lie directly under the mound core; (2) ordinary, single‑direction drills that appear in open settlement soils or former fields. The puzzle is whether the cross‑hatched type represents everyday ground preparation for mound building or a symbolic act carried out to “feed” or bless the dead.

The functional view

(Rowley‑Conwy and others) holds that ploughing a chalk or gravel surface before a barrow loosens turf, yields neat sods for construction and helps drainage; the criss‑cross pattern simply reflects practical efficiency—two passes at right‑angles break up the ground fastest.

The ritual view

(Henning‑Berg, Nielsen et al.) notes that these furrows occur exactly where mortuary rites took place and argues they form a deliberate offering: labour invested, crops symbolised, territory claimed for the ancestors. The same ard could serve agriculture elsewhere, but under a barrow its strokes became part of the funerary performance.

Most recent studies accept a middle ground: cross‑ploughing probably did both jobs at once—providing construction material and enacting a brief, visible rite of transition from farmland to ancestral monument. Linear furrows in settlement contexts, like those just found at Bubeneč, are taken as straightforward cultivation. Key tests ahead are tighter dating of the ploughed surfaces, micro‑analysis of furrow soils to spot cultivation residues, and wider geophysical prospection to see how consistent the pattern really is.

2012 Radio Prague

Below is a verbatim transcript of the final exchange in the 2012 Radio Prague interview where archaeologist Petra Maříková Vlčková explains why some prehistoric furrows are labelled “ritual ploughing.” The clip begins with the interviewer’s question and ends just before the closing credits. Minor hesitations (uh/um) and repeated words have been removed for readability; no other edits have been made. Interviewer (Christian Falvey): What kind of rituals might we be talking about in the case of these ritual furrows? Petra Maříková Vlčková: “Well, who knows? No one knows for sure. It’s called ritual ploughing because the cross‑hatched marks are usually found underneath burial mounds. We can only suggest that when you want to bury someone in the ground you also want to give him—or her—the possibility of eternal life, and for that you need to fulfil certain conditions, like giving a blessing or providing some means of subsistence. “In an agricultural society that subsistence is crops, so ploughing the soil could symbolise feeding the dead or perhaps opening the earth in a special, sacred way. But—and I always add this—archaeologists tend to use the word ritual when we don’t really know what something means, so it becomes an easy answer to almost everything. In other words, we can’t say with certainty; we can only observe the context and propose that ploughing beneath a barrow was probably not practical farming but part of the ceremony.”(End of quoted passage. The programme then moves on to closing remarks and credits.)