Contents

- 1 Anciens Arsenaux Neolithic settlement, Sion (canton Valais, Switzerland)

- 2 Setting in landscape and geology

- 3 Cultural corridor of the upper Rhône

- 4 Stratigraphic sequence and key occupation phases

- 5 Headline discoveries

- 6 Why the site is important

- 7 Context in modern heritage

- 8 Anciens Arsenaux in its wider human landscape

- 9 Living folklore that still colours the hills

- 10 Recommended resources

- 11 Flintbek LA 3 (Northern Germany, close to Denmark)

- 12 Guldager-Nygård (Jutland, Denmark)

- 13 Torsted-Langagergård (Denmark)

- 14 Key Takeaways

"Upper Rhone Valley" by palbion is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Anciens Arsenaux Neolithic settlement, Sion (canton Valais, Switzerland)

Setting in landscape and geology

Sion lies midway along the upper Rhône Valley, an east‑west trench gouged by repeated Pleistocene glaciers and now flanked by the Pennine and Bernese Alps. The settlement area sits on the alluvial fan of the Sionne torrent, a cone of well‑sorted sands and gravels that projects onto the wider Rhône flood‑plain. Bedrock gneisses and schists crop out on the valley walls, but at the site the stratigraphy is entirely Quaternary: stacked fan‑deposits alternating with thin brown soils formed during lulls in flooding. (Arkeonews)

The fan provided three assets to early farmers:

- a gently sloping surface high enough to avoid regular flooding,

- free‑draining soils easy to hoe or scratch‑plough,

- year‑round springs issuing at the fan toe.

Today the place-name Les Arsenaux recalls a 19th‑century military storehouse, but since 2017 the canton’s archives project has exposed almost 800 m² of Neolithic layers sealed by up to ten metres of torrent gravel. (Nature)

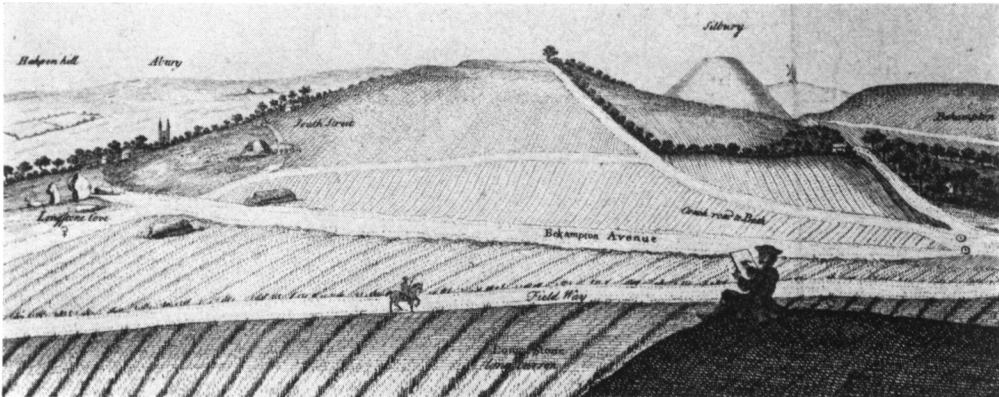

The ploughmarks groups 364 65,500 and 499 at the Anciens Arsenaux excavations

Cultural corridor of the upper Rhône

The Rhône Valley is a natural trans‑Alpine route: Neolithic groups coming north from the Po plain meet streams of Rhône‑side communities moving west from the Swiss plateau. Pottery and stone tool styles at Sion echo both spheres:

- VBQ (Vasi a Bocca Quadrata) cultural traits typical of early Italian farming camps,

- later Planig‑Friedberg ware culture elements from the Rhine basin.

By the late 5th millennium BC the valley floor already hosted seasonal herding and river‑bank arable plots; Anciens Arsenaux marks one of the first fixed farmsteads on a stable terrace.

Hoofprints at Sion–Anciens Arsenaux

Stratigraphic sequence and key occupation phases

| Ensemble | Cal BC span (Bayesian, 30 dates) | Character | Diagnostic finds |

|---|---|---|---|

| N1 | 5244 – 4914 | Early Neolithic hamlet of post‑holes, hearths, pits | VBQ pottery, cereal grains (wheat & barley), cattle/sheep/pig bones, sickle blades, querns |

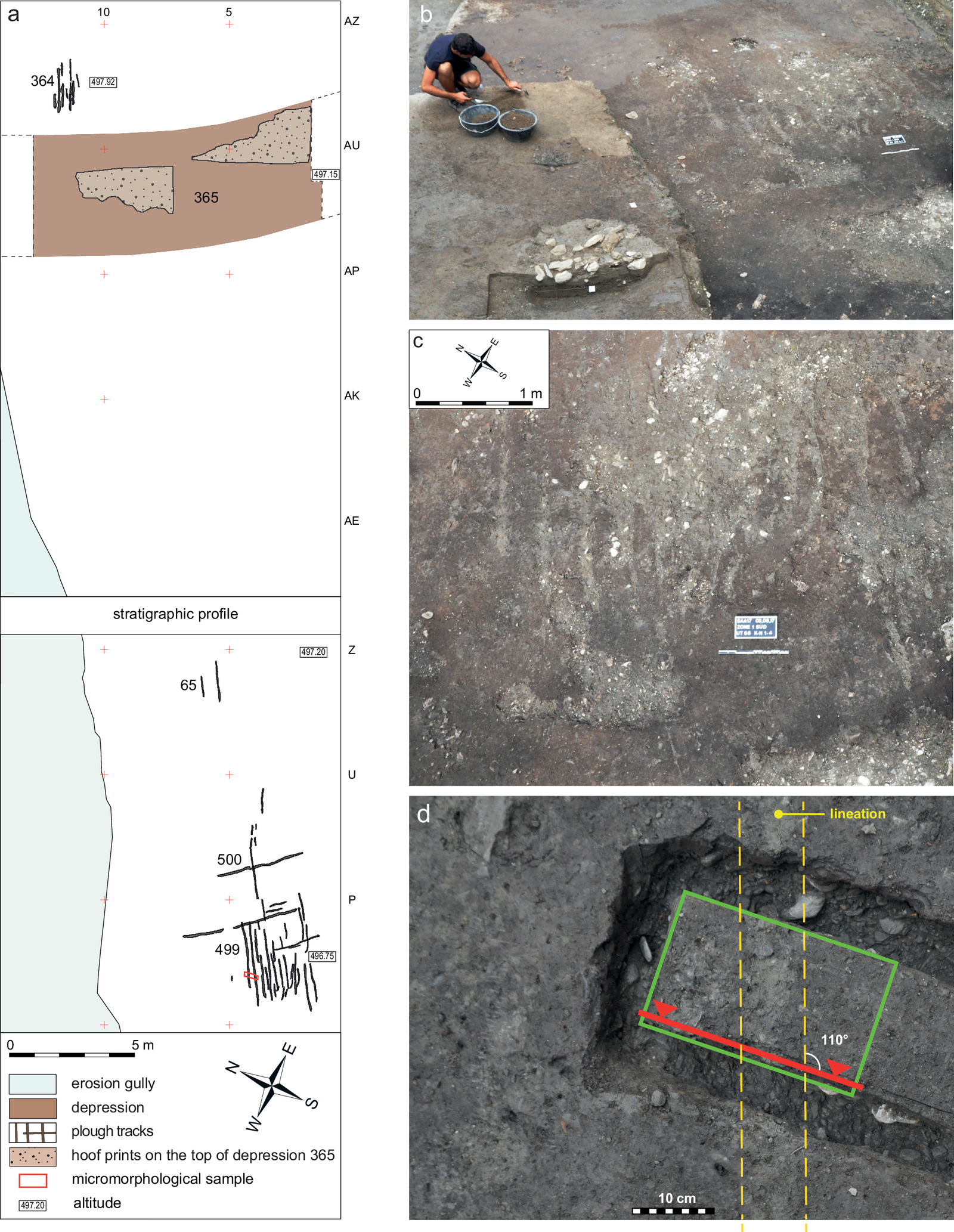

| AG1 | 5116 – 4708 | Humus episode sealing N1, plough marks & hoof‑prints | 30 m² of parallel ard furrows + cattle/goat hoofprints; no structures |

| N2 | 4680 – 4350 | Reoccupation on new soil | Planig‑Friedberg decorated ware, Polished Stone Adzes, red deer antler tools |

| Younger lenses | 4300 – 3500 | Episodic use, seasonal flooding | Mixed late Neolithic coarseware, charcoal lenses, alluvial sands |

Headline discoveries

Europe’s oldest plough furrows – groups 364, 65, 500 & 499 are U‑shaped grooves 8–12 cm deep, running ENE–WSW across AG1; Micromorphology shows raked chalk Grit and polish identical to experimental ard tracks. Bayesian modelling dates them c. 5100–4700 BC, a millennium before Danish‑German examples. (Nature)

Hoof‑prints in the same horizon – clear bovine prints and smaller caprine (goat-like) tracks overlap some furrows, strongly suggesting that animal traction was used, rather than hand‑drawn scratch‑ploughs. (Nature)

Early mixed farming package – charred emmer, naked barley and flax; cattle (dominant), sheep/goat and pigs; red deer and ibex show continued hunting.

"Middle neolithic site at Quinzano 01" by Schuppi is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

VBQ‑style pottery – hollow‑bottomed bowls and square‑mouthed jars link Sion directly to the Po‑Liguria cultural stream, underlining the Rhône–Po corridor.

Seasonal flood events – every occupation lens is blanketed by coarse torrent sand; the alternation explains the exceptional Preservation of delicate plough impressions.

Why the site is important

- Pushes back plough chronology – Sion shows traction ploughing possibly up to 600–800 years earlier than seen so far, elsewhere in northern Europe, forcing a re‑think of how fast heavy farming spread.

- Animal power integral to the “Neolithic package” – hoof‑prints and ard marks appear within two centuries of the first cereal farming here, not as a late innovation.

- Alpine funnel for ideas – ceramic and tool styles prove the upper Rhône was a mixing zone between Mediterranean and north‑alpine cultures by 5000 BC.

- Geo‑archaeological time‑capsule – rapid fan sedimentation sealed each surface, giving a ten‑metre notebook of alternating human and natural events unmatched in the western Alps.

Context in modern heritage

The excavation has been conserved beneath the new Valais Cantonal Archives; Photogrammetry and micromorphology blocks are stored at the cantonal archaeology unit (ARIA SA). Public interpretation panels on site explain the plough furrows and their role in Europe‑wide farming history; a planned Rhone‑valley trail will link Anciens Arsenaux with the later Copper‑Age stelae cemetery of Petit‑Chasseur, illustrating 2,000 years of cultural change within a 2 km stretch of Sion’s terrace.

Anciens Arsenaux in its wider human landscape

From glacier‑gouged valley to wine‑terrace

Sion occupies a sunny pocket halfway along the Upper Rhône where two torrents – the Sionne and the Lianne – spill coarse fans of gneiss‑ and schist‑gravel onto the main valley floor. The Anciens Arsenaux dig sits on the apex of the Sionne alluvial fan, a free‑draining cone 10 m thick that has protected successive occupation surfaces under fresh gravel veneers (Wikipedia). The climate. Sheltered by 3 000 m peaks, the inner Valais is one of the driest corners of Switzerland (≤600 mm rain/yr), a factor that still favours cereal plots and the celebrated cut into the same fan margin today.

A corridor of peoples before and after the Neolithic

| Period | Snap‑shot around Sion | Anchor site(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Final Palaeolithic / Mesolithic (11 000–6000 BC) | Hunters pass the Rhône–Toce watershed; seasonal camps cluster round perennial springs such as Blick Mead upstream. | Blick Mead, Bramois rock‑shelter |

| Late Neolithic to Copper Age (c. 4500–2500 BC) | Terrace farmsteads like Anciens Arsenaux and Petit‑Chasseur thrive; fine‑pebble stelae cemetery at Petit‑Chasseur shows emerging Alpine chiefdoms. | Petit‑Chasseur stelae field |

| Bronze Age | The upper Rhône becomes an east‑west trade line linking Alpine copper to Rhône delta. Cairn burials on the valley shoulders overlook river crossings. | Aproz Necropolis |

| Iron Age (Seduni tribe) | Celtic Seduni control the valley; oppidum on the Valeria hill issues coinage. At the end of the 1st century BC, Sion was the capital of the Seduni, one of the four Celtic tribes of the Valais. Julius Caesar mentions them as Nantuates Sedunos Veragrosque | Valeria oppidum traces (Wikipedia) |

| Roman Sedunum (late 1st BC–5th AD) | Baths, villas and a vicus spread across both torrent fans; Sion is praised by Augustus as capital of the Seduni (Wikipedia). | Roman bath under St‑Théodule church |

| Medieval bishopric (6th –18th c.) | Sion becomes the seat of powerful prince‑bishops. Twin hill‑top strongholds Valère basilica (c. 1040–13th c.) and Tourbillon castle (1297‑1308) dominate the fan apex (Valais, Wikipedia). | World’s oldest playable organ in Valère (c. 1430) (Wikipedia) |

| Modern era | 1788 fire destroys Tourbillon; 19th‑c. arsenal gives the excavation its modern name; present‑day Sion is the wine‑capital of Valais. |

Iron Age Oppidum

The earlier phrase “Valeria oppidum traces” refers to the Celtic oppidum on Sion’s Valère hill, not to be confused with the Spanish Roman colonia of Valeria. The statement is geographically correct once the hill’s local name is rendered as Valère (or “Valère/Valeria hill”) and tied explicitly to the Seduni oppidum.

Archaeologists have identified late Iron‑Age / early Roman occupation on and around that hill and on neighbouring Tourbillon; this is taken to be the oppidum (fortified tribal centre) of the Seduni, the Celtic tribe whose capital Julius Caesar lists in his Gallic War.

- “Leur oppidum est l’actuelle Sion …” (Their oppidum is present‑day Sion) – overview of Valais Celtic archaeology (annitrek.com)

Living folklore that still colours the hills

The Dragon of Tourbillon. A local tale says the flames that razed Tourbillon castle in 1788 were the breath of a dragon chained deep inside the hill; frescoes in the castle chapel show St George slaying the beast (ausflug.blog). Some guides still warn that tremors on hot summer days are the creature turning in its sleep.

The Witch of Belalp. Up‑valley, a 15th‑century legend tells of a widow who could summon storms; each January skiers in broomsticks hurtle down the Belalp slopes in the Hexe downhill to placate her spirit (Ghoomo Beyond Boundaries).

St Theodul and the Devil’s Bell. Valais’ first bishop is said to have forced the Devil to carry a church bell over the Theodul Pass; iron filings from that bell supposedly echo in every Valais foundry (Wikipedia).These stories reinforce a picture of this location as one of significant influence in both history and prehistory. One wonders is this may well be the site of the earliest ploughing here: Surely, the location that has the economic head start, is most likely to retain that leadership, and with it, potentially, the increased authority that might naturally fall on people that need to create better organisations structures, as well as technologies?

Recommended resources

Van Willigen et al. 2024, Humanities & Social Sciences Communications (plough study) (Nature); Valais Cantonal Archaeology Service press releases June 2017 (Archaeology Wiki); site stratigraphy and ceramic analysis in ARIA SA technical reports 2018‑22.

Below are three Danish Neolithic sites with well-documented pre-monument ard (plough) marks that are repeatedly cited in the literature and that together give a good cross-section through regional soils, monument types, and interpretive debates (practical cultivation vs. ritual preparation).

From the Danish cluster of early ploughing sites mentioned in the Sion report, three stand out for their detailed archaeological data: Flintbek LA 3, Guldager-Nygård, and Torsted-Langagergård. Below is a description and comparison of these sites and a basic analysis of what they can tell us.:

Flintbek LA 3 - Plough Marks - photo by D Stoltenberg |

Flintbek LA 3 Grave A - Photo by D Stoltenberg |

Flintbek LA 3 (Northern Germany, close to Denmark)

Flintbek dates to the Mid-4th millennium BCE (c. 3700 BCE). It is famous for its clear ard marks (plough tracks) associated with a causewayed enclosure and megalithic burials.

Finds & Features:

- More than 30 parallel furrows, some crosscutting others, indicating repeated ploughing.

- Association with a long barrow suggests a ritual component, possibly preparing the ground before the erection of monuments.

- Micromorphological studies show the marks were made by a simple wooden ard drawn by cattle, evidenced by nearby cattle hoofprints.

Guldager-Nygård (Jutland, Denmark)

Dating from before the end of the 4th millennium BCE, this site includes one of the earliest well-preserved ploughing patterns in Denmark.

Finds & Features:

- The site shows multiple sets of linear ard marks, some overlapping.

- Evidence suggests a shift from cultivation to non-utilitarian activity, implying that certain ploughed areas may have been “closed” by cross-ploughing before monument construction.

- Nearby finds of pottery and flint tools indicate a settlement context, with the ploughing likely connected to both practical agriculture and ceremonial land-marking.

"Hand plough (11005644673)" by Thomas Quine is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Torsted-Langagergård (Denmark)

Also dated before the end of the 4th millennium BCE, this site is known for crosswise ploughing beneath a burial mound.

Finds & Features:

- Archaeological excavations revealed cross-ploughing (perpendicular furrows), which is often interpreted as a symbolic “deactivation” of farmland before converting it into a burial or ritual site.

- Radiocarbon dates align with the Funnel beaker culture (TRB), highlighting the transitional nature of land use from farming to ceremonial activity.

- Associated animal bones and flint debitage suggest mixed-use landscapes.

Comparison of Ploughing Styles

Flintbek LA 3 shows a combination of functional ploughing (straight, parallel furrows) and later crosscutting, possibly tied to ritual preparation before monument construction.

Guldager-Nygård appears to represent mainly linear, cultivation-oriented ploughing, though the overlapping furrows hint at phases of re-use or symbolic closure.

Torsted-Langagergård is the clearest case of deliberate crosswise ploughing, strongly interpreted as ritualistic, since it directly precedes the building of a burial mound.

Key Takeaways

These Danish sites suggest that cross-ploughing could symbolize a transformation of land from a productive field to a sacred space. Monument construction (Long Barrows or mounds) is seen overlay these existing ploughed surfaces, reinforcing the idea of the creation of sacred or otherwise set-aside space for the revering of ancestors, the deceased or ancestral spirits. However, we are also seeing this cross ploughing without monument construction, so must be cautious in coming to any rapid conclusion.

Similar patterns at South Street Barrow (Wiltshire) and Sion–Anciens Arsenaux (Switzerland) strengthen the argument that crosswise ploughing is a ritual act rather than agricultural.