Sutton Common – Doncaster

Sutton Common is an early Iron Age fort/enclosure site just north of Doncaster, A key feature of this “marsh fort” is that it seems to use the surrounding marsh land as part of its defence – a twist on the more common hill fort. A further point of interest is the two enclosures link with a causeway accross the dividing waterway.

Sutton Common has been excavated from 1997. The work is being carried out by the University of Exeter (Department of Archaeology) and Hull (Wetlands Archaeology and Environments Research Centre). Funded by English Heritage, excavations are due to be completed by 2003. Click here to access the University of Essex website for Sutton Common.

Excavation of this site is still ongoing, so this page is expected to develop in line with the excavation.

Air photos of Sutton Common, in both cases, the smaller enclosure is on the left. Also note the other earthworks shown in the left picture. Pictures from English Heritage.

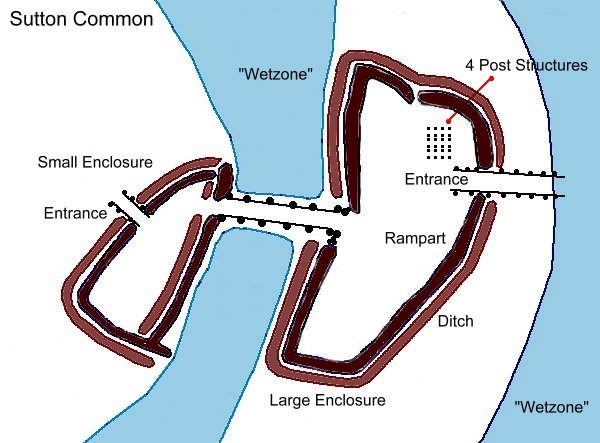

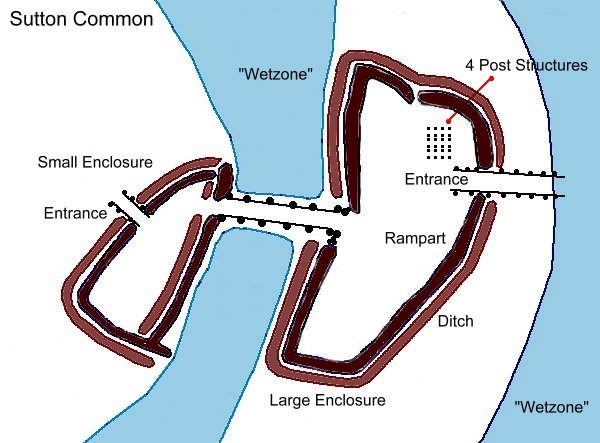

Plan of the enclosures with clickzones for more detail. Based on plan from University of Exeter. The dark brown represents the rampart, which was formed from a timber box filled with earth with a low whitestone facing. The light brown area shows the ditches. Notice that the smaller encolsure has an interior ditch, leading to the suggestion that it was really a gateway enclosure for the main enclosure – it’s defences service to strengthen the latter’s defences, not it’s own. The blue area shows the areas likely to have been waterlogged for most of the year – serving to enhance the defences of the enclosure system.

25 July 2002 – English Heritage Press Release.

UNINHABITED “GHOST VILLAGE” FOUND AT YORKSHIRE IRON AGE SITE

English Heritage Dig Reveals Mystery of Country’s Biggest Marshland Fort

An English Heritage funded excavation at Sutton Common near Askern in South Yorkshire is bringing to light remains of a mysterious and unique Iron Age site-almost a “ghost village” of seemingly scarcely inhabited buildings set within the biggest marshland fort in England.

One of the most intriguing finds is the remains of a wooden well with a brushwood floor nearly two metres below the surface-first glimpsed three years ago but now completely uncovered for the first time.

Originally protected by impassable marshes, the fort (which covers the area of two football fields) comprises two enormous and enigmatic enclosures, one with a grand entrance, linked by what appears to be a ceremonial walkway. The site has defied explanation since it was discovered over a century ago. Now archaeologists taking part in the Sutton Common Project, designed to regenerate the landscape in this former coalfields area, have uncovered yet more mysteries in their attempt to solve the puzzle of why the enclosures, which date from about 600 to 400 BC, were built.

Director of excavations Robert Van de Noort of Exeter University said: “Within the ramparts we have uncovered the remains of several round houses, boundaries and a well and also of a wide avenue through the site. But we have found no evidence, such as bone or pottery or of the repair of any of the structures, to show that anyone actually lived here. It is as if this were a kind of ghost village, scarcely ever inhabited, and may mean that Sutton Common was primarily a symbolic or ceremonial place, rather than a political or economic centre.”

Even the well, where it would be usual to find items dropped or thrown in, offers no proof that it was ever used. It appears to be filled with clean sediment.

David Miles, Chief Archaeologist at English Heritage said: “The Sutton Common fort is set to make a significant contribution to our understanding of the Iron Age regionally and nationally. English Heritage is happy to contribute to the Project’s work and will fund further excavations next year with the aim of resolving the enigma of this mysterious and atmospheric site.”

Earlier excavations (some also funded by English Heritage) revealed stone revetted ramparts, a palisade and waterlogged remains in the ditches, including what looks like a wheel and a ladder. The entrance to the larger enclosure would have been highly elaborate and lends credence to the idea that the post-lined avenue over a causeway linking the two was more than simply functional.

Co-director of excavations Henry Chapman of the University of Hull said: “The building techniques and architecture of the ramparts closely resemble those of early Iron Age hillforts elsewhere in England. However, instead of building the fort on a hill, the impassable wetlands were used to create an impregnable site, the biggest marshland fort in England.”

Since 1997 an ambitious conservation programme (The Sutton Common Project)has been under way aimed at restoring the grandeur of the marshland setting and delivering a range of environmental benefits to the region. This includes a re-wetting scheme for the surrounding land.

Ian Carstairs, trustee of landowners CCT, said: “The Sutton Common project represents an unparalleled example of co-operation of government agencies, including English Heritage, English Nature, the Countryside Agency and DEFRA, together with local organisations and people. It is a wonderful example of what can be achieved when we all work together.”

Informed comment on the lack of finds

“There has been some not inconsiderable debate on the possible use of the Sutton Common enclosure for ritual purpose, the proponents for this identify the lack of artifacts as being significant and the main thrust of their argument can be summed up as follows; From the three excavations carried out at the site by Whiting in 1933-35, Sydes and Parker Pearson in 1987-93 and most recently by Van der Noort in 2002, only the excavations by Sydes and Parker Pearson turned up any metal work. A single Bronze Age palstave axe, section of a bronze age Dirk blade, Part of a bronze cauldron rim (?), a segment (terminal end) of a Roman peninsular brooch, a copper alloy ring of undeterminable date, and an unidentifiable Iron object, which was described in the site report as part of a brooch pin (?). All of these objects were surface finds and therefore uncertified.

In terms of datable artefacts several Iron Age type glass beads were found on the surface within the large enclosure, after stripping and several pieces of extremely friable low/unevenly fired pottery were discovered in trenches D and F. On analysis they were thought to be Late Iron age. Recent excavations at sites such as Pickburn Leys and Sykehouse (where a significant amount of I.A pottery has been recovered) have shown that local Iron Age sites were not aceramic and that the lack of pottery is more likely due to soil conditions and the poor quality of locally manufactured wares. Other than the preserved wood fragments there are no datable finds from stratified levels from either of the three series of excavations. The radio carbon dates on the preserved wood have suggested an Early Iron Age date for the construction and reconstruction of the timber and stone palisade/rampart. The Sutton Common ladder (a notched single stake of wood c 2m in length) does have parallels in the Iron Age and the discovery of a saddle quern on the site might back up the argument of Iron Age use of the site prior to c 200 B.C when they are superseded by the beehive quern.

The lack of datable metal stone, bone, glass or any other items from stratified levels on the site is very puzzling especially one views the site as having been occupied either in the Iron age or later. The lack of metal work present in stratified deposits cannot be explained by the activities treasure hunters or other outside infuence, given the overall lack of finds and the large extent of the excavtains to date. The preservation of wood has been generally quite good producing over the years a number of artifacts, such as the wheel (?), the ladder etc, so if the site were inhabited during the Iron Age, why have there not been found pieces of wooden bowls, looms, baskets or found anything in the way of food waste such as seeds, pips, grains or more animal bones (if human skull fragments can survive, why not animal bones, though there were fragments of sheep bone excavated from the ditch of the large enclosure)?

In respect of the projected four poster features in the larger enclosure interpreted as structures, they could possibly be Roman or Romano-British, but this is unlikely for the following reason. A number of sherds of 2nd Century locally produced Roman pottery have been found as surface scatters in the small enclosure, suggesting perhaps a later Iron age habitational use of part of the site, where we can perhaps see native people adopting available Roman goods.

However there is a clear lack of evidence for Romano-British cultural material such as pottery from the large enclosure. If the structures are thought to be Roman, where is the evidence for prolonged or even short term habitation, particularly discarded pottery in the ditches or in post holes or evidence from environmental sampling of food processing or consumption. Square structures are known in Britain before the Roman conquest. There is good evidence from excavations at such sites as Danbury Hill Fort of square structures, which have been interpreted on different sites as granaries, look out or fighting platforms and even as shrines (depending on their situation within or without a site). The idea of the site having been a pagan religious enclosure, which was kept ceremonially clean is not too wild an idea, especially when compared with Stonehenge, which was used successively for thousands of years but has produced very little in the terms of finds. It has long been argued that this site was ritually cleaned which seems a plausible explanation when considering that other henge monuments are rich in cultural material either meaningfully placed or discarded as rubbish.” Peter Robinson, Keeper of Archaeology, Doncaster Museum and Art Gallery. 2002

Other Research

“Carbonised grain is known from four sites in the Trent-Tyne region…. ….The only example west of the wolds is the wheat recovered from a trench through a rampart of one of the enigmatic enclosures on Sutton Common (whiting 1938, Camp B).” Challis and Harding Later Prehistory from the Trent to the Tyne. 1975.