Late Neolithic Palisaded Enclosure

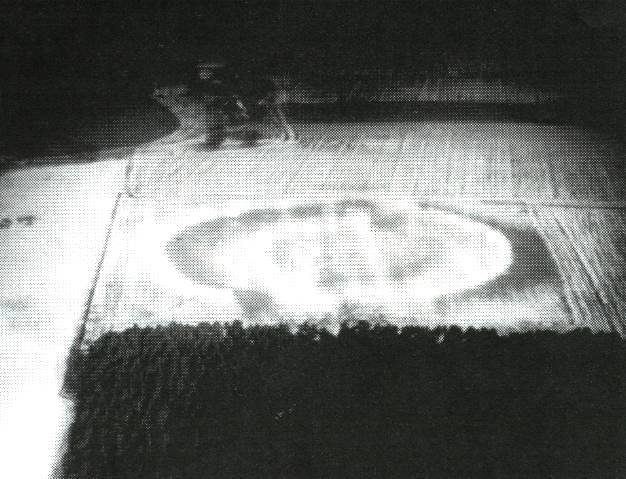

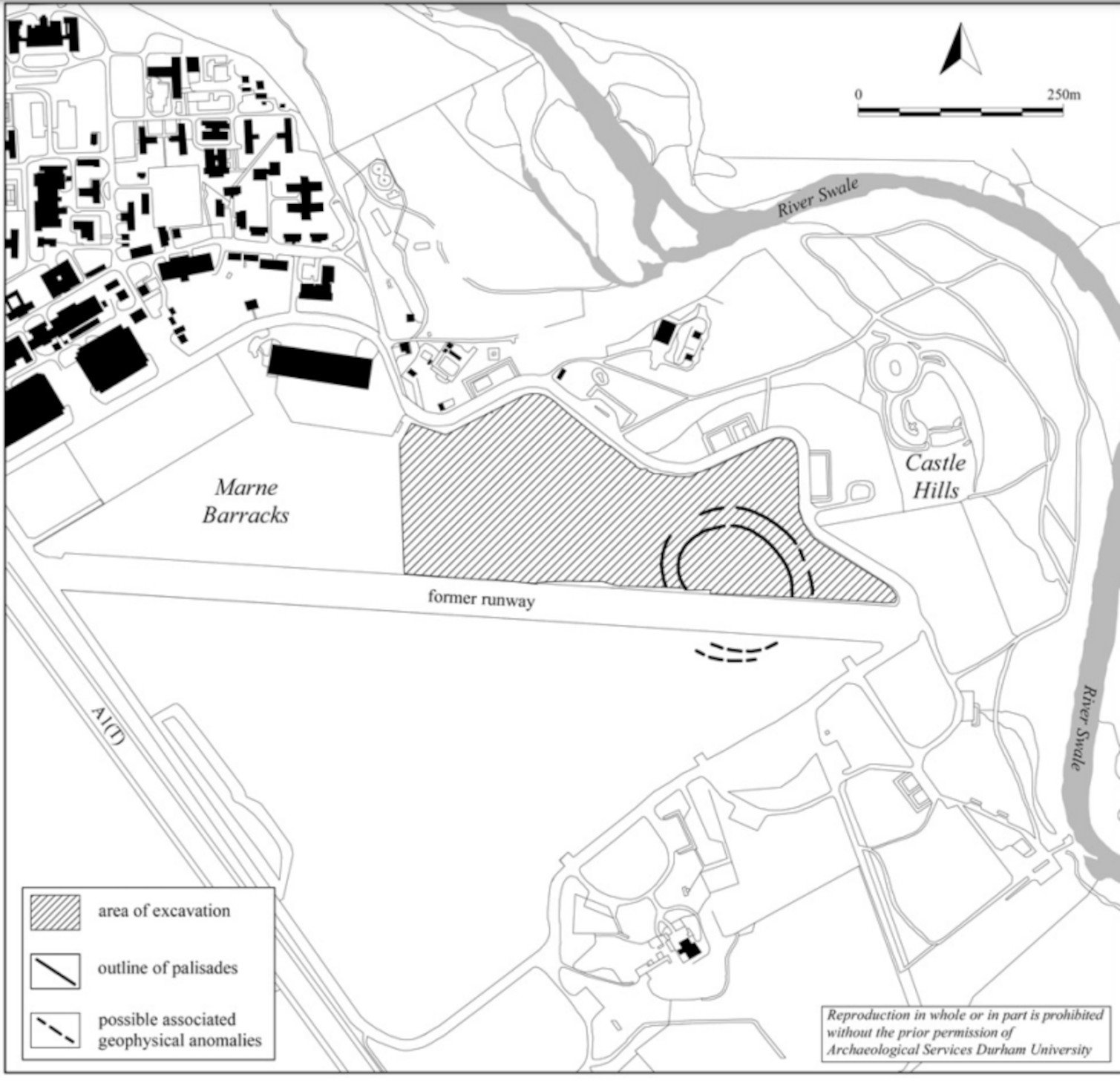

The recent discovery at Catterick has unveiled a significant Late Neolithic palisaded enclosure, shedding light on the prehistoric landscape of North Yorkshire. Excavations revealed two concentric sub-circular palisades, with the outermost having a diameter of up to 200 meters and the inner one measuring approximately 175 meters in diameter.

To quote the excavation report:

"An open-area excavation conducted in advance of development at Marne Barracks, Catterick, in 2004 identified a relatively rare Late Neolithic ‘palisaded’ enclosure and other features. Approximately 55% of the enclosure was exposed. It consisted of two concentric sub-circular palisades with diameters up to 175 m and 200 m respectively. Each palisade consisted of a double circuit of posts, with the posts being c. 1 m apart from centre to centre.

Many of the posts on the western side of the monument had been sufficiently carbonised for the remains of individual posts to be identifiable. Twenty-one radiocarbon ages were determined, and Bayesian modelling has produced a date estimate of 2530–2310 cal BC for the start of construction of the monument. This date matches well with new dates for the construction of Silbury Hill, the appearance of Beaker pottery in graves, the Amesbury Archer, and the timber circles at Durrington Walls, for example. The Marne Barracks monument exhibits significant differences to other known examples of this type, and is in some respects unique. In particular, the ‘paired post’ arrangement of a double circuit of posts in each palisade is unparalleled in any other known example.

Ritual Landscape

The apparent width of the entrances to the Marne enclosure is also at variance with other known sites, though this may in part be an artefact of post-depositional survival. The monument sits in a ritual landscape and, like a few others of its type, is close to water and a hill or large mound from where the activities taking place within the enclosure might have been observed.

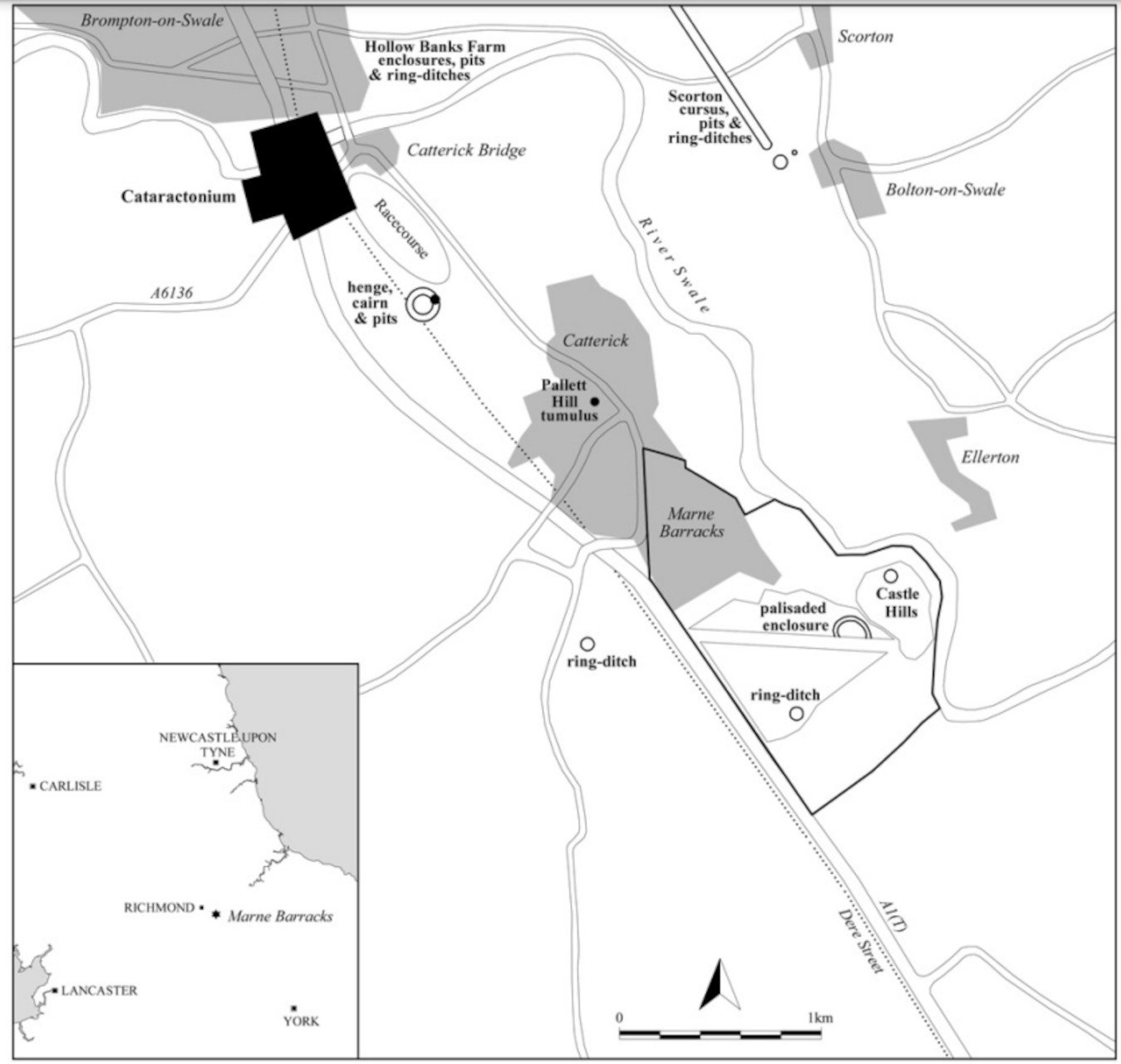

Do the nearby hill, the entrances, and the arrangement of the uprights all relate to control of physical and visual access into, or out of, the monument? A number of broadly contemporary monuments, all within 5 km of Marne Barracks, contribute to a significant Neolithic ritual focus on the River Swale gravels. The complex of cursus and henge monuments at Thornborough and the henges at Nunwick, Hutton Moor, and Cana Barn all lie less than 25 km to the south, in the Swale-Ure Interfluve."

Commentary

These structures are composed of a double circuit of posts, spaced about 1 meter apart from centre to centre, which is a unique feature not paralleled in other known examples. The carbonised remains of the posts on the western side have allowed for precise radiocarbon dating, placing the start of construction around 2530–2310 cal BC. This timeline coincides with other significant Neolithic events, such as the construction of Silbury Hill and the appearance of Beaker pottery.

The Marne Barracks monument, as it is known, exhibits unique characteristics, particularly the 'paired post' arrangement and the width of the entrances, which differ from other similar sites. Its location in a ritual landscape near water and a hill suggests a strategic placement for controlling physical and visual access. The discovery contributes to our understanding of the Neolithic ritual focus in the region, linking it to a complex of cursus and henge monuments within the River Swale gravels.

The excavation of the Late Neolithic palisaded enclosure at Catterick has not only revealed the structural components of the site but also a range of artifacts that provide insight into the activities and culture of the people who built and used the enclosure.

Findings

Among the findings, large cobbles containing oyster shells and some animal bones were discovered, although no man-made artifacts were reported in this context. These organic materials suggest that the site may have been used for communal gatherings where food consumption played a role. The absence of man-made artifacts in certain layers could indicate specific cultural practices or rituals that were performed at the site. The discovery of these artifacts contributes to the broader understanding of Neolithic life and rituals in the region, complementing the architectural significance of the palisaded enclosure itself. The artifacts, along with the structural findings, are helping archaeologists piece together the social and cultural landscape of Neolithic Britain.

The animal bones found at the Late Neolithic palisaded enclosure in Catterick are part of the intriguing array of organic materials unearthed at the site. Although the specific types of animal bones have not been detailed in the available resources, their presence is a testament to the activities that took place within the enclosure. Typically, animal bones at such sites can provide valuable insights into the diet, domestication practices, and ritual activities of the Neolithic communities. They may represent the remains of consumed livestock or could be indicative of ritualistic offerings or ceremonies. The analysis of these bones through methods such as zooarchaeology could reveal information on species, age, and butchery practices, offering a window into the agricultural and culinary aspects of the period. The discovery of animal bones alongside oyster shells suggests a varied diet and possibly complex food preparation and consumption rituals. These findings contribute to the broader narrative of Neolithic life, highlighting the intricate relationship between the people, their environment, and their spiritual practices. The bones, therefore, are not just remnants of the past but are keys to unlocking the stories of the Neolithic inhabitants of Catterick.

The Late Neolithic palisaded enclosure at Catterick has yielded a fascinating array of organic materials, providing a glimpse into the past activities and environmental conditions. The site's organic deposits included charred plant remains, which are indicative of the vegetation that was present in the area and the diet of the Neolithic people. Pollen analysis from these deposits can offer insights into the ancient landscape, revealing what types of plants were growing nearby and how the land was being used. Additionally, the presence of carbonised wood suggests that timber was an essential construction material and also points to possible practices involving fire, such as clearing land or ritual activities. The discovery of these organic materials, alongside the structural features and animal bones, paints a comprehensive picture of the Neolithic period at this site, highlighting the interconnectedness of daily life, the environment, and ritual practices.

The Late Neolithic palisaded enclosure at Catterick has yielded a fascinating array of organic materials, providing a glimpse into the past activities and environmental conditions. The site's organic deposits included charred plant remains, which are indicative of the vegetation that was present in the area and the diet of the Neolithic people. Pollen analysis from these deposits can offer insights into the ancient landscape, revealing what types of plants were growing nearby and how the land was being used. Additionally, the presence of carbonised wood suggests that timber was an essential construction material and also points to possible practices involving fire, such as clearing land or ritual activities. The discovery of these organic materials, alongside the structural features and animal bones, paints a comprehensive picture of the Neolithic period at this site, highlighting the interconnectedness of daily life, the environment, and ritual practices.

The charred plant remains found at the Late Neolithic palisaded enclosure at Catterick have provided a valuable insight into the local environment and subsistence practices of the period. The analysis of these remains has revealed the presence of cereal grains and chaff, with a predominance of glume base fragments and other chaff components, excluding charcoal. Cereal grain was the next most frequent component identified within the samples. These findings suggest that the Neolithic inhabitants of the area practised some form of agriculture, likely cultivating and processing cereals for food. The presence of chaff, which is the husk surrounding the grains, indicates that processing took place near the site, possibly as part of a harvest ritual or communal activity. The identification of these plant remains not only informs us about the diet of the people but also about the agricultural practices of the time, providing a link to the broader landscape management and use of resources.

The specific types of cereal grains identified in the charred remains from the Late Neolithic palisaded enclosure at Catterick are not detailed in the search results. However, it is common for such archaeological contexts to yield cereals like wheat (Triticum spp.), barley (Hordeum vulgare), and sometimes millet (Panicum miliaceum) or oats (Avena spp.). These grains were staples of Neolithic agriculture and would have been cultivated, harvested, and processed by the communities. The presence of cereal grains at the site aligns with the broader pattern of Neolithic subsistence strategies, which included a shift from hunting and gathering to farming, allowing for more permanent settlements and complex societal structures. The analysis of these grains can provide insights into ancient agricultural practices, crop varieties, and the seasonality of farming activities. It also contributes to our understanding of the diet and economy of the Neolithic people, reflecting a significant change in human history towards food production and Sedentism.

The importance of Catterick

The recent archaeological discoveries at Catterick have positioned it as a site of significant historical importance in Northern England. The uncovering of the Neolithic palisaded enclosure, a rare and monumental structure, has shed light on the prehistoric landscape of Yorkshire. This enclosure, unique in the region, is part of a broader complex of ancient sites including the cursus at Scotton, which is the largest of its kind in Yorkshire, and the henge at the racecourse. These structures are intricately linked with the Thornborough Monument complex, often referred to as 'The Stonehenge of the North' due to its ceremonial significance.

The location of Catterick within this wider ritual landscape, alongside the Roman remains that indicate a long history of occupation and strategic importance, underscores the area's status as a key ancient site. The Roman town of Cataractonium, modern-day Catterick, was a hub of military and economic activity, playing a crucial role in the region's development during the Roman occupation of Britain. The combination of prehistoric and Roman archaeological elements at Catterick enriches our understanding of the past and highlights the continuity and complexity of human activity in this area over millennia. The palisaded enclosure at Marne Barracks, for example, provides a fascinating glimpse into the Late Neolithic period, with its double circuit of posts and significant differences from other known examples, adding to the uniqueness of Catterick's historical landscape. In conclusion, the confluence of these diverse archaeological features indeed makes Catterick one of the most important ancient sites in the North of England, offering invaluable insights into the region's prehistoric and Roman heritage.

The recognition of Catterick's historical importance may not be as prominent in public discourse for several reasons. Firstly, the current use of Catterick as a major military base is over-shadowing its historical significance, focusing contemporary narratives on its modern utility rather than its ancient past. There is also a lack of accessible public information about Catterick that put's in into the correct context. We are back to the usual situation, where we lose all of our ancient sites to development because Historic England will not perform their duty of care for our ancient sites, which includes anticipating that an area is going to hold many more riches, and to take steps to protect, not just known monuments, but also the others everyone knows are there, that have yet to be found.

A big part of what they do, is not tell us, so we don't ask them to do their job. That's the way it is. Collectively, we don't care because we don't know because, we believe the people we pay to protect our most important sites will do their job and tell us when our most important heritage sites are in danger. Only, they never do, and this site, to me, proves it. This site only went public, after it was gone, at a time when I was actively engaged with the archaeological world and English Heritage, trying to encourage those institutions to stop allowing such sites to be destroyed.

The narratives surrounding historical sites are often shaped by cultural and academic trends, trends which include an assumption that there's nothing more to find, and that it's OK to wait for a development to find what was assumed was not there, and the assured destruction that follows. Catterick could have been a haven for the archaeological tourist, instead it's home to the quarry, and the blandness of a space that's had its soul removed. Do you think this find triggered a frantic search to find ways to protect anything that is left and yet to be found? Well no, that's not actually their job. They are never going to tell us, so it all just gets forgotten, 5000-year-old structures which barely exist in our imagination because talking about them, is too political.

The degradation of historical sites like the Henge and the palisaded enclosure at Catterick is not just a loss of archaeological integrity but a diminishment of our collective heritage.

These sites, as evidenced by the Vale of Mowbray's importance as the largest of its kind anywhere. But our authorities want rid of these sites, it's clear, both by their lack of action, and by their lack of words, telling us about our most important heritage, and why we need to protect it. Catterick is our most important heritage, do you hear them shout about this? But also, let's face it, collectively, do we care? Nope, no-one cares about their heritage that much. I guess we'd better enjoy what we have while it's here. Dream our dreams, knowing our archaeologists are never going to know much at all, since they wait for the quarry to choose their targets, and set the depth of the research allowed.

We are losing immense historical and cultural value, representing a period of religious fervour and architectural ingenuity during the Neolithic era within our region. The Catterick henge, despite its flattened state in antiquity, was part of this broader narrative, contributing to our understanding of Neolithic Britain, same with this the only neolithic palisaded enclosure in Yorkshire, both now lost, their sacred environment devastated.

Ultimately, the responsibility lies with both the custodians of these sites and the wider public to recognize and preserve the legacy of the Catterick monument complex. It is through collective awareness and action that we can ensure the endurance of these testaments to our prehistoric past, allowing future generations to appreciate and learn from the ingenuity of our ancestors. The degradation observed at the Henge and other monuments serves as a reminder of the fragility of our historical sites and the urgent need to safeguard them for posterity.

I apologize for the rant, it was originally much, much longer.