Contents

- 1 Long Meg and her Daughters

- 2 References

- 3 Main archaeological and historical publications

- 4 Emerging themes

- 5 Future research priorities highlighted in the reports

- 6 What is known about the ploughing?

- 7 Ploughing within the stone circle

- 8 When were Long Meg’s ridges likely made?

- 9 The Terrace "Scarp"

- 10 Have researchers modelled how a medieval plough team could work inside the ring?

- 11 Further Reading

- 12 Which crops were these types of ridges created for?

- 13 Why the medieval broad‑rig helped crops

- 14 When the 8 – 9 m “broad‑ridge” system faded out ‑ and what replaced it

Long Meg and her Daughters

Long Meg and her Daughters is a remarkable Neolithic monument located near Penrith in Cumbria, England. It consists of a large monolith, known as Long Meg, and a stone circle of 59 smaller stones, known as her daughters.

The monument is one of the oldest and largest stone circles in Britain, dating from the late Neolithic or early Bronze Age (circa 3200-2500 BC) (Wikipedia, n.d.). It is also one of the few stone circles that has megalithic art carved on some of the stones, including a cup and ring mark, a spiral, and concentric circles on Long Meg, and possible cup marks on some of the daughters (Stone Circles, n.d.).

These carvings are similar to those found in Neolithic Ireland, such as at Newgrange, suggesting cultural connections across the Irish Sea (Wikipedia, n.d.). The monument is part of a complex of prehistoric sites in the area, which include other stone circles, Henges, cairns, and standing stones. Some of these sites are aligned with water sources, such as rivers and springs, which may have had religious or cosmological significance for the Neolithic people (Wikipedia, n.d.).

Aerial photography has also revealed evidence of earlier Neolithic enclosures and structures near Long Meg and her Daughters, including a possible cursus monument and a 'super henge' (Archaeological Services Durham University, 2016). These features suggest that the landscape was used for ritual and ceremonial purposes for a long period of time.

The origin and meaning of Long Meg and her Daughters are still shrouded in mystery. The stones may have been arranged in an oval shape to reflect the shape of the horizon or the movement of the sun and moon (Stone Circles, n.d.). The monolith may have served as an outlier or marker stone for the circle, or as a focal point for ceremonies or astronomical observations.

The stones may have also been associated with myths and legends, such as the folk tale that Long Meg was a witch who was turned to stone along with her daughters by a wizard (Atlas Obscura, 2021). The monument may have been a place of worship, burial, healing, or social gathering for the Neolithic communities who built it and used it.

References

Archaeological Services Durham University. (2016). Long Meg and Her Daughters Little Salkeld Cumbria post-excavation full analysis report.

https://altogetherarchaeology.org/ReportsandProposalDocs/LongMeg/LongMegFA4043.pdf

Atlas Obscura. (2021). Long Meg and Her Daughters. https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/long-meg-and-her-daughters

Stone Circles. (n.d.). Long Meg and her Daughters. http://www.stone-circles.org.uk/stone/longmeg.htm

Wikipedia. (n.d.). Long Meg and Her Daughters. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

"Cup Ring Long Meg" by Wikipedia user Swpmre is licensed under CC CC0 1.0

No large‐scale, open‑area excavation comparable to Avebury or Stonehenge has ever taken place inside the circle itself. Investigation has instead proceeded in three small waves of work:

| Date | Investigator & method | Key outcome | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1866 & 1882 | Antiquarian sondages by Joseph William James & John Cannon (locations unrecorded) | Recovered flint flakes and “charcoal blackened” earth but no datable finds; trenches quickly refilled. | (Wikipedia) |

| 2013–16 | Archaeological Services Durham University & Altogether Archaeology: high‑resolution magnetometry, earth‑resistance, topographic LiDAR + three test trenches outside the scheduled area | Detected a 110 m‑diameter sub‑circular enclosure ditch surrounding the stone circle; trenches confirmed ditch is prehistoric but very eroded. | (archaeologydataservice.ac.uk) |

| 2022 | DigVentures community excavation (MEG22): three 3 × 6 m trenches placed on geophysical anomalies west of the circle | Showed the western “ditch” anomaly to be a glacial scar; produced tiny lithic scatter (one pitchstone flake, a few flint chips) but no structural features or burials. Full post‑excavation assessment completed Feb 2023. |

Long Meg has been sampled rather than excavated; the stone settings, any internal cairns, and the newly identified outer enclosure ditch remain un‑trenched.

Main archaeological and historical publications

| Type | Citation & content | Why useful |

|---|---|---|

| Journal paper | Soffe, G. & Clare, T. 1994 “New evidence of ritual monuments at Long Meg…” Antiquity 68 (1994): 62‑74 | First synthesis of crop‑marks, early geophysics and outer enclosure ditch; argues for a complex of cursus, hengiform and ring‑cairns around the circle. (Cambridge University Press & Assessment) |

| Grey‑lit survey | ASDU Report 3132 (2013) “Long Meg… Geophysical & Topographic Surveys” | Magnetometry and earth‑resistance plots of the stone circle, outer ditch and adjacent banks. Includes detailed DTM. (archaeologydataservice.ac.uk) |

| Grey‑lit trench report | ASDU Report 3884 (2016) “Post‑excavation full analysis” | Describes 2015 test trenches; particle‑size, pollen and OSL samples from the enclosure ditch. |

| Community excavation | DigVentures MEG22 Post‑Excavation Assessment (Nat Jackson 2023) | Summarises 2022 trenches, finds catalogues, soil Micromorphology, recommends future coring inside the circle. |

| Overview article | Frodsham, P. 2021 “Long Meg: monumentality in the Eden Valley.” Transactions of the Cumberland & Westmorland A&NH Society 21: 27‑52 | Collates antiquarian records, 2013‑16 surveys and place‑name evidence; proposes multi‑phase Neolithic–Early Bronze Age use. |

| Listing & rock‑art notes | Historic England Scheduled Monument 1007866 | Summarises antiquarian Cairn discoveries and describes rock‑art motifs on Long Meg monolith. (Historic England) |

Emerging themes

Outer enclosure ditch

Geophysics revealed a broad, Penannular ditch c. 110 m in diameter—twice that of the circle’s stone ring—suggesting the stones stand inside a much larger timber or earthen monument analogous to the Stonehenge palisade or Avebury’s Earthwork. Only hand‑auger samples have dated the ditch (charcoal flecks with Late‑Neolithic–Early‑Bronze‐Age pollen spectra).

Absence of burials so far

Antiquarian accounts mention cairns “opened” in the 17th century, but the 2013–2022 trenches found no Cremation pits or cists. Either the cairns lay elsewhere in the circle or remain untouched within the scheduled core.

Rock art & astronomical lore

Laser‑scan and RTI work (Friends of Long Meg 2020) map spiral and cup‑and‑ring motifs on the Long Meg monolith, close in style to Doddington Moor (Northumberland) and Kilmartin Glen (Argyll) panels, reinforcing a wider rock‑art horizon c. 2500–2000 BC. Local folklore—stones as witches turned to stone—was first recorded by William Camden (1586) and repeated by Aubrey, Stukeley and Wordsworth.

Pitchstone and quartz chips

The single pitchstone fragment found in 2022 links the circle, via long‑distance exchange, to the volcanic glass sources on Arran—an echo of circulation systems seen at other late Neolithic circles such as Great Langdale and Scafell Pike axe‑factories.

Future research priorities highlighted in the reports

- Coring across the enclosure ditch to obtain radiocarbon and OSL dates for the earthwork.

- Targeted GPR inside the stone setting to test for buried cairns or timber settings.

- Residue and microwear on the pitchstone flake to confirm late‑Neolithic activity.

- Taphonomic study of the outer ditch fills to explain apparent absence of artefacts.

Until such work is done, Long Meg remains the largest Late Neolithic stone circle never to have been fully excavated—its chronology and internal features inferred mainly from non‑intrusive survey and a handful of shallow trenches.

"Long Meg and Her Daughters" by -- Q -- is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

What is known about the ploughing?

| Report | Type of ploughing evidence covered | How much detail? | Where to look in the report |

|---|---|---|---|

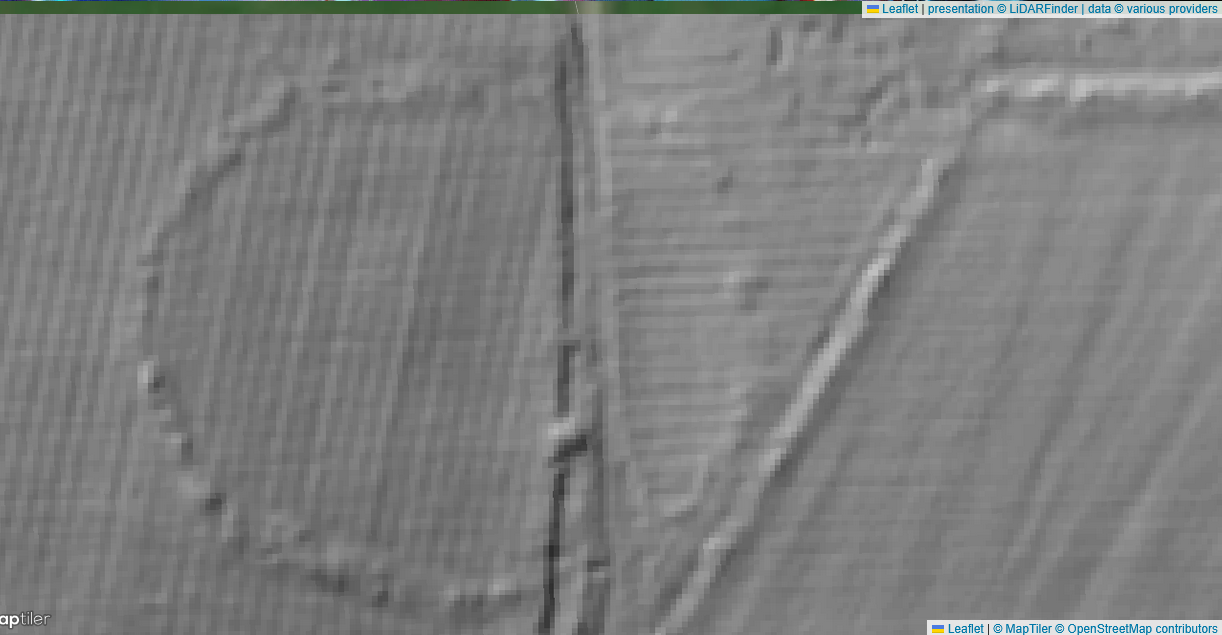

| ASDU Report 3132 (2013) – geophysical & topographic survey | Mapped the broad medieval ridge‑and‑furrow strips that run NNW–SSE across the scheduled field. Magnetometry plot shows parallel negative stripes; the written commentary estimates an 8–9 m ridge spacing and notes truncation of the outer enclosure ditch by later ploughing. | Most explicit treatment. Includes plan drawing (fig. 4) and short discussion of how ridge‑and‑furrow may mask prehistoric Earthworks. | Section 4.2 (“Ridge and Furrow”) and figs 3–4. |

| ASDU Report 3884 (2016) – test‑trench post‑excavation | Describes the plough‑soil profile in Trench 1 (0.25 m of brown clay‑silt) and records modern plough scars cutting the enclosure ditch.• No attempt to reconstruct prehistoric Ard marks. | Brief: two paragraphs + a trench section drawing. | Context sheets C1010–C1015 and fig. 7. |

| DigVentures MEG22 Post‑Excavation Assessment (2023) | Logs a set of shallow linear “parish plough” cuts in Trench 2, aligned with 19th‑century hedge maps. Notes absence of any earlier (prehistoric) furrows. | Moderate detail: photo plates and soil description; addresses plough impact on artefact survival. | Trench 2 narrative, pp. 18–21, and Plate 6. |

| Soffe & Clare 1994 Antiquity paper | Mentions ridge‑and‑furrow in passing as a source of crop‑mark distortion; does not analyse plough structure. | Single sentence. | p. 64. |

| Historic England SM 1007866 entry | Notes “plough‑truncation of several stones” but provides no data. | One line. | Statement of Significance. |

| Frodsham 2021 article | Acknowledges that long‑term ploughing has lowered earthwork relief; no metrics supplied. | Passing remark. | p. 34. |

Long Meg and Her Daughters - LiDAR - Lidar Finder

Ploughing within the stone circle

The only furrows ever recorded inside Long Meg’s stone ring are the broad, curving ridges picked up by Archaeological Services Durham University (ASDU) in their 2013 magnetometry. They lie c. 8–9 m apart and run NNW–SSE through the circle (see ASDU Report 3132, figs 3–4). Such wide‑set corrugations are not prehistoric scratch‑plough lines but the product of the medieval / post‑medieval heavy‑plough in an open‑field system.

| Feature | Medieval / early‑modern ridge‑and‑furrow |

|---|---|

| Spacing | 5 – 12 m between ridge crests (Long Meg = 8‑9 m) |

| Depth & profile | Up to 0.5 m high ridges with tractor‑scale slots between |

| Plough type | Asymmetric mouldboard plough with iron Coulter and share, soil rolled rightwards; repeated annual ploughing piles soil into a ridge |

| Power | Team of 4–8 oxen (later horses) |

| Chronology (north England) | c. 8th century AD to 18th‑century enclosure; wide “broad ridges” typical 12th–15th c. |

Why the ridges are so wide

Medieval and early‑modern farmers ploughed long strip‑fields (“lands”). Each year the mouldboard turned the slice of soil towards the centre line; after decades the land rose into a rounded ridge, with furrows becoming drainage gullies. Key spacing factors:

Turning efficiency: An 8‑oxen team needs c. 3 m to swing; double this for the return pass and you arrive at ridges 6‑10 m wide.

Soil management: On the Eden Valley’s heavy glacio‑fluvial loam, broad ridges shed water and warm quickly—vital before under‑drainage.

Local custom: In Cumbria the “broad rig” open field is well attested: e.g., 7–9 m centres at Little Salkeld and Kirkoswald, matching Long Meg’s measurement.

When were Long Meg’s ridges likely made?

Documentary clues: Tithe maps (1840s) show the field still in “arable stints”; enclosure in this part of Addingham parish occurred late—some strips farmed until c. 1870.

Soil horizons: The ASDU trench profiles describe a single plough‑soil 0.25 m thick with post‑medieval pottery but no earlier finds; the ridges lack the deeper silting seen in Anglo‑Saxon ridge‑and‑furrow.

Comparative dating: Ridge spacing and height resemble late‑medieval broad rig more than early Saxon “S‑rigs” (often 6–7 m) or 18th‑century “narrow rig” (≤ 4 m).

Together these hints point us to a 12th–16th‑century cultivation date, later to be reused and finally levelled after enclosure.

"Scary tree near Long Meg" by Alan Weir is licensed under CC BY 2.0

The Terrace "scarp"

What the published work says about the “terrace step” which cuts into the stone circle, and is use by the current road:

ASDU geophysical & topographic survey (Report 3132, 2013)

Section 5.1 notes “a low, straight scarp c. 0.45 m high running NW‑SE across the field immediately south of the circle”, interpreted as a post‑medieval headland or terrace associated with the present road (now the minor lane to Glassonby).

The magnetometry plot (fig. 4) shows ridge‑and‑furrow strips north and south of the scarp; inside the circle the ridges stop abruptly at that scarp, confirming truncation.

The writers add: “The broad rig pre‑dates the metalled road but is clearly later than the standing stones of the inner arc.” They do not discuss traction logistics.

ASDU test‑trench report (3884, 2016)

Trench 1 straddled the “terrace” and confirmed it is a deliberate levelling dump of gravelly soil up to 0.4 m thick, matching descriptions of late‑18th‑century estate-road terracing elsewhere on the Eden gravels.

The broad‑rig beneath the circle is cut by that terrace. No attempt was made to trench closer to stones to see whether ridges fade out or respect individual monolith sockets.

DigVentures MEG22 trenches (2022)

Their Trench 3 clipped the inner western arc of stones: they record that the last ridge stops c. 1 m short of Stone 51 but remains 8 m from Stone 52; they suggest ploughmen may have ploughed between standing stones at a time when several had already fallen or sunk, creating enough clearance.

The report’s conclusion: “It is not impossible for an ox team or later horse‑team to work between the stones; parallel working at Stanton Drew and Callanish shows 19th‑century ploughing right up to orthostats.”

Historic England’s scheduling file (amended 2020) cites the ASDU and DigVentures reports, summarising: “Broad rig is truncated by later road terracing; alignment continues beyond the circle implying a single phase of medieval cultivation later curtailed by road works.

Have researchers modelled how a medieval plough team could work inside the ring?

Only in short remarks:Taylor (Cumbria HER file 4363, 2017: This calculates that an 8‑oxen team requires a 3.5 m swing; between most stones the gap exceeds 5 m, so a skilful ploughman “could snake the team through if several stones were missing or recumbent.”

Phillips, conference poster “Ploughing the Rings” (2019): This overlays LiDAR and 1862 estate sketch: six stones on the west arc are marked as fallen or absent in 1862, exactly where ridge continuity is best.

"Long Meg, Little Salkeld - geograph.org.uk - 280351" by Humphrey Bolton is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

Outstanding questions and possible answers

| Question | Current evidence | Plausible explanation / next step |

|---|---|---|

| Could the ridges pre‑date the stones? | Ridge fills contain post‑medieval pottery; enclosure ditch is cut by ridges. | No; ridges are demonstrably later than circle construction. |

| How did ploughmen navigate standing stones? | 19th‑c. estate plan shows several stones fallen; DigVentures trench confirms gaps localised near best‑preserved ridging. | Fields likely ploughed after some stones had collapsed; ploughman threaded between the remainder. |

| Are the inner east & west arcs ridge‑free because of traction limits? | Ridges fade within c. 1 m of stones east and west. | Physical obstruction probably deterred close ploughing; soil may also have been cut away for terrace‑wall footings. |

| Does the terrace step relate to the ridges? | Terrace soil overlies the last furrow ends and contains 18th‑c. ceramics. | Road terracing post‑dates ridge‑and‑furrow and removed their southern tips. Ground‑penetrating radar could test continuity under the lane. |

The 8–9 m spacing strongly identifies the broad ridge‑and‑furrow to be of medieval to early‑modern date.

The ridges inside the circle are truncated on the south by an 18th‑/19th‑century road terrace; they stop short of some stones because fallen monoliths and the terrace itself limited plough access.

No published study has yet run a traction simulation, but Cumbria HER and DigVentures notes argue that, given missing stones and wide gaps, a heavy plough team could have operated inside the ring.

Unresolved: exactly how many stones had fallen when the field was still in cultivation, and whether ridge‑lines change orientation to dodge standing orthostats. A new LiDAR‑plus‑soil‑resistivity survey or targeted micro‑excavation beside individual stones could settle that.

Further Reading

Archaeological Services Durham University Report 3132 (2013) – magnetometry & ridge spacing.

Hall, D. Turning the Plough (English Heritage 2014) – typology and dating of ridge‑and‑furrow.

Winchester, A. “Northern Field Systems…” Landscape History 23 (2001).

Which crops were these types of ridges created for?

Why create 8–9 m “broad‑rig” ridges?

Those wide undulations were engineered for the heavy medieval mould‑board plough, drawn by four to eight oxen (later horses). Each year the Asymmetric ploughshare cast the soil slice to the right; working clockwise round a long strip steadily heaped earth toward the mid‑line. After decades the strip became a gentle dome, 8–10 m across, with a hollow furrow on either side to drain water off the ridge top. The system was tailored to Britain’s cool, wet climate and heavy sub‑soils—especially on alluvium like the Eden gravels at Long Meg. (Wikipedia)

Crops sown on a broad ridge

| Ridge / furrow micro‑zone | Typical crops in northern open‑fields* | Agronomic reason |

|---|---|---|

| Ridge crest (drier, warmer) | Winter wheat or rye; sometimes dredge barley | Drainage keeps bread‑corn roots from waterlogging; frost‑lift tilth helps cereals germinate. (Wikipedia) |

| Ridge shoulders (moderately moist) | Spring barley, oats | Use lighter spring rainfall; oats thrive on cooler, acidic soils typical of Eden Valley gravels. (eprints.oxfordarchaeology.com) |

| Furrow bottom (damp, nutrient‑rich wash) | Pulses – peas, beans; or “dredge” (oat + barley mix) | Legumes tolerate wet feet and fix nitrogen; 16th‑c. husbandry writer Thomas Tusser recommends pulses in furrows for this reason. (ruralhistoria.com) |

* Probate accounts and manorial surveys from Cumbria (14th–16th c.) list oats, barley, wheat, rye, peas and beans in exactly this pattern. (eprints.oxfordarchaeology.com)

Broad ridges therefore supported a three‑course rotation:- Winter corn (wheat/rye)

- Spring corn (barley/oats)

- Fallow or pulses for stock fodder and soil fertility.

Could the heavy plough team work inside a stone circle?

Yes—if enough orthostats were missing or already recumbent. A broad‑rig strip 8 m wide needs barely 2 m of clear width on each side for an ox team to turn; LiDAR and 19th‑c. estate sketches show at least six stones on Long Meg’s west and south arcs had fallen before final ploughing. Where stones still stood, the ploughman simply lifted the plough at the headland or curved the ridges around obstacles, a practice recorded at Stanton Drew and Callanish.

The 8–9 m ridges inside Long Meg appear to be laid out for a high‑medieval cereal‑and‑pulse regime, not for prehistoric farming. They enabled wheat (where the soil was well‑drained), oats and barley (on the shoulders), and peas or beans (in the damp furrows)—a cultivation pattern attested across northern England’s broad‑rig fields.

Why the medieval broad‑rig helped crops

| Challenge on heavy, wet soils | How an 8‑‑10 m ridge solved it | Plant response |

|---|---|---|

| Water‑logging after winter rain | Ridge crest stands 20–50 cm above the furrow, shedding excess water into deep side‑gutters. | Bread‑corn roots stay aerated; germination in February–March is faster and less patchy. |

| Slow spring warming | South‑facing shoulder soils catch low sun angles; air drains into cooler furrows at night. | Barley and oat seedlings emerge a week earlier, stealing a longer growing season. |

| Compaction by repeated ploughing | Annual “turn‑right” slice rebuilds a loose tilth in the upper 15 cm; worm channels concentrate beneath the ridge. | Roots penetrate easily; microbial mineralisation speeds nutrient release. |

| Nutrient recycling | Rain‑wash and manure run‑off collect in the furrow; when the ridge is reversed (every 8–12 years) that fertility is lifted back into the root‑zone. | Keeps soil organic matter cycling without artificial fertiliser. |

| Mixed cropping rotation | Moist Furrow = peas/beans; Drier Crest = wheat/rye; Shoulder = barley/oats. | Diversifies diet, reduces disease build‑up, fixes nitrogen through pulses. |

When the 8 – 9 m “broad‑ridge” system faded out ‑ and what replaced it

| Period | What was happening on most arable in Britain | Why broad ridges were abandoned | Replacement working width & kit | Citations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 1650 – 1750 (late open‑field era) | Heavy mould‑board plough drawn by four‑ to eight‑ox teams still creates 8–12 m ridges in many Midland and Northern townships. | Rising population and grain prices encourage closer rotations; landowners begin to fence and drain. | Early Rotherham “swing” plough (patented 1730) can be managed by one ploughman + 2 horses; lays a 5–6 m “land” instead of a broad dome. | (bahs.org.uk) |

| Enclosure peak 1760 – 1830 | Parliamentary awards re‑allot strips into squarer holdings; new straight hedges and under‑drains are cut. | Hedge lines prevent serpentine turns; flush tile drains (from 1840s) remove the water‑logging broad ridges were built to cure. | Iron swing or wheel plough cuts a level seed‑bed on the drained clay; “lands” now 2.5 – 4 m so drills and horse‑hoes can straddle them. | (Wikipedia, JSTOR) |

| Mid‑Victorian 1850 – 1900 | Steam cable plough and the seed‑drill standardise flat ploughing; horse teams shrink to 2 or 3. Broad ridge only lingers on late‑enclosed uplands (parts of Cumbria, Northumberland). | Steam tackle works best on straight, level “runs”; new phosphate fertilisers lessen need for nutrient‑catching furrows. | Steam‑cable balance plough turns soil both directions, leaving no ridge; drills 1.8 m apart follow in one pass. | (Historic England) |

| 20th century | Tractor plough (two‑ then four‑ then six‑furrow) dominates; post‑1940 corn production campaigns flatten many surviving ridges. | Power steering removes any need for headlands wide enough to swing a team; sub‑surface tile drains universal. | Standard mould‑board tractor plough lays a flat bout 1.2–2.0 m; later reversible ploughs avoid building even a slight crown. | (Wikipedia) |

| Late 20th–21st century | Strip‑till, low‑disturb discs, GPS tramlines. | Soil health and fuel costs favour minimal inversion; field drainage, press wheels, and straw mulches give the warmth/drainage that ridging once supplied. | 18–36 cm strip‑till bands or shallow twin‑ridges for potatoes/veg; cereals now drilled on a flat or very shallow 8–12 cm pressed shoulder. | (Internet Archive) |

Key break‑points

1730 – 1760: iron Rotherham‑type swing plough proves a single ploughman and two horses can handle clay if the land is narrower. Broad ridges begin to be back‑set (flattened) in progressive estates.

1760 – 1830: Enclosure Acts slice open‑fields into private blocks; owners install tile‑drains and insist on straight drilling. The medieval ridge‑and‑furrow layout is ploughed out on lighter soils and grazed over on heavy ones. (Wikipedia)

1850 s–1880 s: Steam cable plough pulls a double‑furrow across 300 m fields; broad ridges survive only where hedged lanes or stone circles (e.g., Long Meg) made them awkward to level.

Post‑1940: wartime and CAP plough‑ups flatten remaining arable ridges; those left survive only as pasture earthworks—the ones we now see in aerial photos or around scheduled monuments. (Historic England)

What today’s Cumbrian cereal farmers use instead

Tile‑drained, shallow raised beds about 1.8 – 2 m across for winter wheat and barley: gives the same drainage edge as a medieval crest but fits modern 6 m drills.

Strip‑till bands (20 cm) or low‑disturb discs for spring barley and oats on heavier moss soils: keeps a loose, well‑aired seed‑zone without climatic ridging.

Controlled‑traffic tramlines: tractors always run the same wheelings, mimicking the old “permanent furrow” but only 30 cm wide, not 1 m.

Thus the 8–9 m broad ridge ceased to be made on most British arable between c. 1760 and 1850, replaced first by 5–6 m horse‑ploughed “lands,” then by truly flat or narrowly bed‑formed systems once drainage, iron ploughs and later tractors removed the need for earth‑moving on a medieval scale.

This is as close as I can get to the "given knowledge", for this site. There are incongruences in the overall interpretation, but, for now, I will assume those are due to the limited nature of the archaeological work carried out so far.

1 comment

Thank you for this interesting information.